Hans van Manen timeline

Hans van Manen has created over 150 choreographies, including his television ballets. His work is performed by more than 100 dance companies worldwide. This timeline provides an overview of his life and his most significant works. For a complete list of all his choreographies, click here.

1960-1969

1960

Black Tights and return to the Netherlands

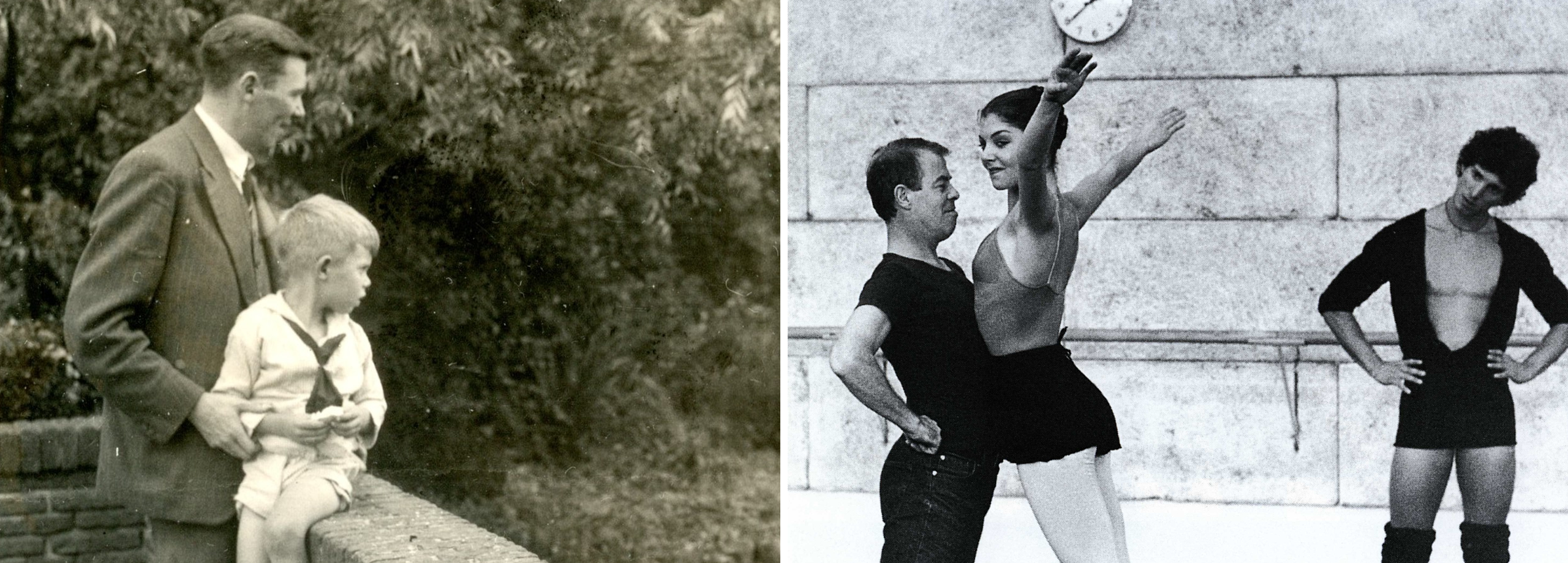

In the spring of 1960, Van Manen and Gérard Lemaître – who are now a couple – are cast for Terence Young’s film Black Tights (in French: 1-2-3-4 ou Les collants noirs), which is filmed in Paris and incorporates sections from Roland Petit’s ballets La Croqueuse de diamants, Cyrano de Bergerac, Deuil en vingt-quatre heures and Carmen.

Klaar af!

During his first period with Nederlands Dans Theater – from 1960 tot 1971 – Van Manen creates nearly thirty ballets in total. In this timeline, we include the most important of them. For a complete list of the works, click here.

The first work he creates for the company on his return from Paris is Klaar af! – een jazzballet. Van Manen had previously choreographed short jazz pieces, but the dazzling, light-hearted and extremely swinging Klaar af! is his first large-scale, ambitious jazz ballet, set to several numbers by Duke Ellington.

1961

Co-artistic director

On 31 July 1961, Van Manen, who has just turned 29, is appointed co-artistic director alongside Benjamin Harkarvy, whose main job is ballet master. Van Manen’s appointment follows an extremely uncertain financial period for the company, whereby there is even a possibility of closure, and Van Manen has been on the point of leaving for the Amsterdams Ballet, directed by Mascha ter Weeme.

Foundation of Dutch National Ballet and subsidy for Nederlands Dans Theater

Around the time of Van Manen’s appointment at Nederlands Dans Theater, the Amsterdams Ballet merges with Gaskell’s Nederlands Ballet to form Dutch National Ballet, initially under the joint leadership of Ter Weeme and Gaskell, but soon with Gaskell as sole artistic director (until 1965). In the early sixties, the two biggest dance companies of the Netherlands were thus led by two ‘artistic giants’ (Van Manen and Gaskell) who – as a consequence of their brief collaboration in the fifties – have a distinct dislike of one another.

Teddy Scholten's Zaterdagavondakkoorden

Through Van Manen’s connections in the television world, Nederlands Dans Theater soon makes regular appearances on television. For example, in the 1960/1961 season, along with the NDT dancers and director Joes Odufré, Van Manen makes the eight-part series Inleiding tot de dans for the VPRO, which also receives high praise from the television critics. Afterwards, from September 1961, Van Manen choreographs a short piece at least once a month for a new TV programme broadcast by the KRO: Zaterdagavondakkoorden, a popular show presented by the singer Teddy Scholten and (in the initial years) her husband Henk Scholten. The show turns Van Manen into a national celebrity. In his many contributions to the show, he tests out all sorts of dance and visual effects that later – in an adapted form – often find their way into his ballets for the theatre.

Cain and Abel

In 1961, Van Manen also creates Cain and Abel, which is even made completely for television. It is directed by Joes Odufré, and the choreography is set to a jazz composition of the same name by Pim Jacobs and to the andante from Giovanni Battista Martini’s Harpsichord Concerto No. 11. In the ballet – which is broadcast on 19 November 1961 – Van Manen transposes the fratricidal strife between the biblical figures Cain and Abel to various locations in an awakening, deserted Amsterdam, including dance scenes at the Amsterdam harbour, in the Prinseneiland district and on the roof of the Bijenkorf department store.

1963

End of dancing career

At the beginning of 1963, Van Manen – then aged thirty – decides to hang up his ballet shoes. It is no longer feasible to combine artistic directorship, being a much sought-after choreographer and appearing on stage himself. However, he does keep dancing for fun till a ripe old age. At the beginning of 2021, a couple of months before his ninetieth birthday, he says, “Sometimes I still dance. In the living room. To a really swinging number. Not for long and not often, and when I do, I do it in a square metre. There’s nothing I like more than keeping it as small as possible. And I imagine I’m surrounded by ten black people, who are watching me and giving me a thumbs-up. Because nobody knows swing like them.”

Symphony in Three Movements

In 1963, Van Manen ventures to use a composition by Igor Stravinsky for the first time. He chooses no less than the extremely complex Symphony in Three Movements, in which the composer gives a summary of his whole oeuvre to date, as it were, in the space of around 23 minutes. At the time, no other choreographer has used the piece (‘Stravinsky specialist’ George Balanchine was only to make a ballet to it in 1972), and in order to fully get to grips with the music, Van Manen listens to it literally hundreds of times. He develops the ideas for the ballet together with Marian Sarstädt – a new dancer who has arrived from the famous Ballet de Cuevas.

First international award

Apart from the State Award for Choreography for Symphony in Three Movements, Van Manen also receives his first international award in 1963, for his performance in his ballets Klaar af! and Concertino during a previous tour to Paris by Nederlands Dans Theater. On 11 July – his 31st birthday – he is presented with the award in a packed Théâtre des Nations (now Théâtre de la Ville) in the French capital. This is followed, in 1964, by the EMS Culture Award for choreography, presented to him and to fellow choreographer Rudi van Dantzig at a banquet at the Kurhaus in Scheveningen, where Zizi Jeanmaire and ten dancers from Roland Petit’s Les Ballets de Paris give a short performance in honour of Van Manen.

1964

Boekenbal

In 1964, under the name Omnibus, Van Manen makes a series of five short dance sketches for the Boekenbal (a ball held on the eve of the Dutch Book Week), which still takes place in the Concertgebouw at the time, attended by Queen Juliana and members of the cabinet. The swinging, hilarious Omnibus turns out to be a huge success with the writers and journalists who are present. Later, Benno Premsela remembers that “the concert hall went completely crazy”. In an interview days before the premiere, Van Manen himself says, “Being funny is much more difficult than being dramatic. Humour is based on surprise, and on spontaneous dénouements. That’s why I made the ballet as quickly as possible. With full concentration, of course, but without lengthy puzzling that might affect the spontaneous character

1965

Essay in de stilte

In the spring of 1965, Van Manen creates his first – and only – work in almost total silence, entitled Essay in de stilte (Essay in Silence), for which he receives a State Award for Choreography for the third time. Not only does the title of the ballet refer to Van Manen’s exploration of different forms of silence (much of the choreography is set to the rhythm of the steps, the dancers’ breathing and an amplified heartbeat), but it also underlines the essence of Van Manen’s already clear mastery: as a ‘writer without words’, he wants to present his story as concisely and powerfully as possible, without superfluous decoration.

Hailed by The New York Times

The first tour of the United States by Nederlands Dans Theater takes place in the summer of 1965. The company performs at the renowned Jacob’s Pillow Festival in Massachusetts, where it dances more than fifty different works in fourteen days. Although the American press pays most attention to the pieces by the American choreographers creating work for Nederlands Dans Theater at the time (such as Glen Tetley, John Butler and Anna Sokolow), it is Van Manen who receives most praise. According to The New York Times, he is “an extraordinarily gifted choreographer who can express a broad and rapidly shifting panorama of emotional situations through movement alone.”

Metaforen - still a success today

Metaforen follows at the end of 1965, created like Essay in de stilte for twelve dancers, with Alexandra Radius, Han Ebbelaar, Marian Sarstädt and Gérard Lemaître as soloists. Of all Van Manen’s more than a hundred and fifty works, this is the oldest one still being performed today – with great success. Using an imaginary mirror wall on stage, Van Manen not only plays a refined game of reflection and symmetry in Metaforen, but also calls into question the traditional gender division in classical ballet, in two duets – the first for Ebbelaar and Lemaître, and the second for Radius and Sarstädt.

1966

Vijf schetsen

In March 1966, Van Manen creates the duet Vijf schetsen in just five days, for his young muses Alexandra Radius and Han Ebbelaar, to Paul Hindemith’s Fünf Stücke für Streichorchester. The ballet marks a breakthrough in the career of the dancing married couple. Alexandra Radius says, “We danced the duet very often, both in the Netherlands and abroad, and it opened up an international career for us, as we also danced it for our audition for American Ballet Theatre” (where the couple worked for two years, from 1968, before making the transition to Dutch National Ballet).

1968

'One of the best in Europe'

In the spring of 1968, Nederlands Dans Theater returns to the United States for a tour lasting two months. For the first time, the company performs in New York, which is the Mecca of modern dance at the time. The performances at City Center are a personal triumph for Van Manen. The Wall Street Journal reports that “Hans van Manen emerges as a great figure in the dance world”. And Clive Barnes, the authoritative critic from The New York Times, writes, “Van Manen is a remarkably gifted and original choreographer; one of the best in Europe. He is imaginative, inventive and daring” and, three days later, “Van Manen is an exceptional technician, and – so rare in ballet – an artist who is extremely aware of what he is doing”.

Stopwatch

Although the bond between Van Manen and managing director Carel Birnie worsens considerably after the tour of America, due to an escalating conflict (Birnie wants the planned tour to Greece to go ahead despite the military coup that has taken place there, which Van Manen fiercely opposes), Van Manen’s productivity at Nederlands Dans Theater remains undiminished. He has already expressly distanced himself from mime and the anecdotal in dance, and in the late sixties this leads to several works that revolve around experimenting with form, whereby he regularly imposes restrictions on himself and his dancers. For instance, he uses a stopwatch for Variomatic, which premieres on 6 July 1968.

Eroticism, aggression and humour

In the autumn of 1968, Van Manen creates Three Pieces, an anniversary ballet, as it is the hundredth production presented by Nederlands Dans Theater since its foundation in 1959. The ballet for sixteen dancers swathed in lingerie, to music by the Polish composer Grazyna Bacewicz, takes place against the cool, white tiled set (designed by Jan van der Wal) of what appears to be a bathroom or swimming pool, and its theme is voyeurism, or as Van Manen puts it, “Watching while others make love.” In this masterpiece, which is later performed by various other companies (as recently as 2016 by Introdans), three elements come together that will often surface in Van Manen’s later works: eroticism, aggression and humour.

1969

Paragon of contemporary abstraction

Squares, which premieres on 24 June 1969 at Théâtre de la Ville, in Paris, grows to become another Van Manen ‘classic’, while at the same time the ballet is still a paragon of contemporary abstraction. It is a ‘danced installation’, as it were, for which Van Manen collaborates with visual artist Bob Bonies, who designs an elevated square dance floor – which can also tilt and reach the vertical – above which a square neon frame is suspended. Within the restrictions – and the possibilities – of this set, Van Manen plays an amazing game of space, light, colour and stark movements, partly inspired by three Gymnopédies by Erik Satie.