‘As a character dancer, you dance as if you’re playing an instrument’

You see them in nearly all the well-known nineteenth-century ballets: character dances – very stylised folk dances that are adapted to the rules of ballet. Although they are certainly not authentic, they have an essential function. “Without the local colour of character, and all its stylistic details, all the big classical productions would soon come to resemble one another”, says Grigori Tchitcherine. The teacher and former Dutch National Ballet dancer is responsible for rehearsing the character dances in Raymonda, which is regarded as the supreme example of how character dancing and pure classical ballet can form a beautiful, inseparable unity.

Text: Astrid van Leeuwen

Photo: Floor Eimers and Vito Mazzeo in the Pas Hongrois from Raymonda (2022) | © Altin Kaftira

About five years ago, Grigori Tchitcherine was visiting the Mariinsky Ballet – where he started his career – and he bumped into William Forsythe. The greatest innovator of the classical ballet idiom got very excited when Grigori (Grisha to his colleagues) told him he’d been teaching character dance at the Dutch National Ballet Academy since 2001. “Forsythe applauded character technique and said that actually all the dancers he worked with ought to have character classes.” Shortly afterwards, Grisha went to a performance of Don Quixote in the Mariinsky Theatre, and while Forsythe thought nobody was watching, Grisha – who was sitting on the front row – could just make out the almost seventy-year-old choreographer frantically gesturing behind the curtain of the director’s box. “He was copying all the movements from the Spanish dance, and he told me later, ‘I’ll do something with that some day’, stressing that for him folk dances are the foundation of all dance.”

‘In an ideal world, every ballet student would have character classes for years on end’

The fact that even the man whose revolutionary choreography has turned ballet completely upside down realised this and propounded it confirms to Grisha once again the enormous importance of character dance in the ballet repertoire and in ballet education. Grisha himself received that training in extenso at the Vaganova Ballet Academy in St Petersburg. “From the age of ten to thirteen, you have classes in historical dance (such as the minuet and gavotte – ed.), and then you get five years of character dance.” Moreover he was chosen along with nine other students to give frequent demonstrations of character classes and character repertoire at the Palucca dance academy in Dresden, during his final years of training. “So as a young ballet student, I became familiar with the whole repertoire, including the phenomenal character dances from Raymonda.”

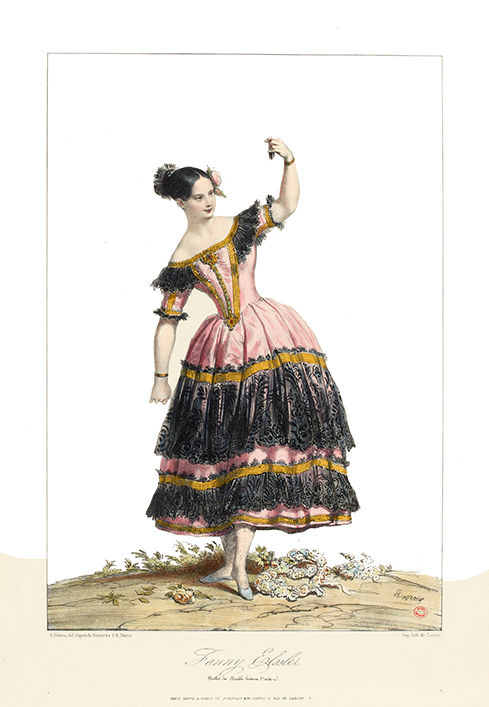

Fanny Elssler

The first instances of character dances date from the eighteenth century. Whereas nowadays the stylised folk dances are only seen in the big full-length productions, ballerinas at the time often performed them as independent ‘show numbers’. The most famous of them was Fanny Elssler (1810-1884), who had tremendous success with her interpretations of dances like the Polish krakowiak, the Italian tarantella and particularly the Spanish cachucha. “This trend”, says Grisha, “was in fact a reflection of what was happening on a daily basis in the wealthy circles in Europe. Masked balls were immensely popular, and in order to attend them you no longer learned the minuet or the gavotte, but rather the mazurka, which was derived from Polish folk dances, and the waltz, which was based on German folk music.” To illustrate this, he produces a booklet from 1891, containing hundreds of figures from the mazurka. “If you wanted to dance at such a ball, you were expected to know all of them.”

Later on, dance critics and historians would unjustly disparage the role of character dances during the heyday of Romantic ballet, in the thirties and forties of the nineteenth century. “The idea arose that there were actually two sorts of ballet: the surreal, ethereal ‘ballet blanc’ and the worldly, colourful variant. But in reality, there were practically no completely ‘white’ ballets, as they often included folk or national dances.” Take the Scottish reel in La Sylphide, for example. “Although in most other cases, they were ‘bucolic’ (pastoral – ed.) dances, in which peasant life is represented in an extremely stylised and idealised form, like the peasant pas de deux in Giselle, for example (a pas de quatre in Dutch National Ballet’s version – ed.).”

Marius Petipa

The most prominent examples of character dances that have stood the test of time are those from the productions by Marius Petipa (1880-1910). The grand master of nineteenth-century Russian ballet, who was of French origin, created numerous ballets (and adaptations of existing ballets) in which a big role was played by Spanish, Hungarian, Russian, Polish, Italian or even Indian dances (the latter totally dreamt up), such as Don Quixote, La Bayadère, Swan Lake, The Nutcracker and Raymonda. Although Petipa, according to Grisha, simply continued the work of predecessors like Filippo Taglioni, Jules Perrot and Arthur Saint-Léon, he did give an enormous boost to the renewed popularity of character dancing. This was partly due to his preference for ‘exotic’ – and at the time often topical – themes. “As he had lived in Spain for a while, he had extensive knowledge of Spanish dances, and of the ‘escuela bolera’, in particular. When I was introduced to it, years ago, I thought in amazement – and with some exaggeration – that ballet didn’t originate in Italy or France at all, as is always assumed, but actually in Spain. There are so many movements and positions in the ‘escuela bolera’ that we nowadays associate with ballet.”

Petipa borrowed the knowledge of Hungarian, Polish and Russian dances largely from his dancers, but for La Bayadère, which is situated in India, he had to make do with the limited sources available at the time and with his own imagination. “He was certainly inspired not only by dancing, but also by the model of a sofa, the colour of a carpet or the shape of a carriage. And he used all that to create an ‘exotic’ atmosphere.”

Drilling, drilling and drilling again

It was Petipa’s assistant Alexander Shiryaev who, along with two of his pupils – Andrei Lopukhov and Alexander Bocharov – compiled the first teaching method for character, which is still used today. It was later published in book form under the title Character Dance. “This method is still part of the Vaganova method, so it also forms the basis for the classes I give at the Dutch National Ballet Academy”.

In an ideal world, says Grisha, every ballet student would have character classes from an early age, and then for years on end, rather than just one. “Unfortunately, that hardly ever happens. Most Western dance companies, including Dutch National Ballet, have plenty of dancers who are only trained in classical ballet technique. This means that it costs a lot of time and energy to teach a character dance, and it’s a question of drilling, drilling and drilling again. And after that, they can only perform that one dance well, so for every subsequent mazurka or Hungarian dance you have to start the whole process again from scratch.”

Raymonda

Looking at all the character repertoire in classical ballet, for Grisha it’s Marius Petipa’s Raymonda that takes the cake. “In classics like Swan Lake and The Nutcracker, the character dances form a separate section; a divertissement to ‘lighten things up’, but in Raymonda they’re interwoven throughout the ballet and they really form a whole with the purely classical dance.”

It was Rachel Beaujean, associate director of Dutch National Ballet, who asked Grisha a few years back to assist her with her new production of Raymonda (which premiered in 2022), both with regard to research and production and to rehearse the character dances. For instance, he took responsibility for the mazurka and the Hungarian dance – “in Rachel’s version, they’re practically identical to Petipa’s original” – and they worked together on the ‘panaderos’, a Spanish-Moorish dance, while artistic director Ted Brandsen was responsible for the Arabian sabre and warriors’ dance.

Flair, panache and arrogance

According to Grisha, Alexander Glazunov, who composed the music for Raymonda, was very inspired by Franz Liszt, just as Tchaikovsky probably was, a few years before Glazunov, for his own ballet compositions. “Composers like Liszt and Brahms based their Hungarian rhapsodies on traditional Hungarian music, but mixed it with gypsy or, as we say today, Roma influences. So just like the character dances, the compositions they’re set to are absolutely not authentic; they’re actually more of a mix of the aristocratic and the temperamental.”

And that, says Grisha, is precisely what you need as a dancer in order to interpret these dances well: “Flair, panache and temperament, but also elegance and a proud bearing that verges on arrogance in the Hungarian dance. And at least equally important: enormous musicality and an understanding of the musical styles concerned. As a character dancer, you dance as if you’re playing an instrument, as it were.”