‘Mata Hari concocted her own imaginary life and created her own reality’

Interview with Ted Brandsen

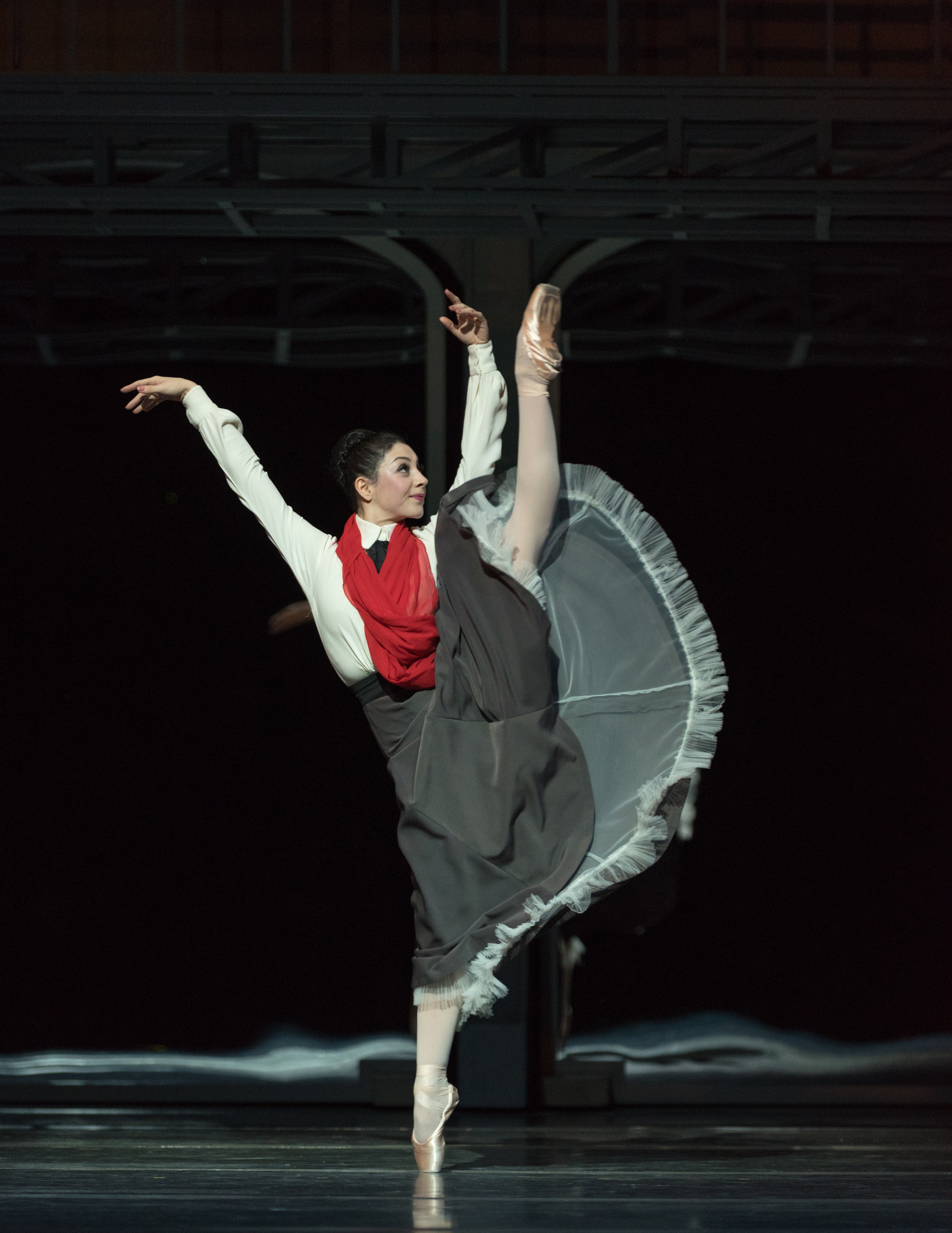

Dutch National Ballet is celebrating its sixtieth anniversary season with a programme made up entirely of productions created in the Netherlands. There are masterpieces by Hans van Manen and Toer van Schayk, new creations by young, promising and internationally acclaimed choreographers, and of course several full-length ballets. Besides the all-time favourite The Nutcracker and the Mouse King and a completely new in-house production of the nineteenth-century ballet Raymonda, the company is also reviving Mata Hari, the successful ballet created in 2016 by artistic director Ted Brandsen, which is based on the life of one of the most iconic women in Dutch history. “Because”, says Brandsen, “it’s important that Dutch National Ballet is innovative not only in the pure dance of the abstract repertoire, but also in telling new stories of our own; stories that distinguish us from other companies around the world”.

Ted Brandsen well remembers how twenty years ago, as the newly appointed artistic director of West Australian Ballet, he looked for inspiration to build up a new repertoire for the company in Perth. “Up to then, I’d made mostly abstract ballets, but I suddenly realised there – at the other side of the world – how much my fellow dancers and I had repeatedly been moved in the preceding years by Rudi van Dantzig’s Romeo and Juliet. By the story, by the enormous power of expression and by all the emotions it conveys. That memory of Rudi’s ballet and the strong emotion it evoked in me there and then inspired me to create my first narrative ballet: Carmen”.

A PREFERENCE FOR STRONG WOMEN

Brandsen’s Carmen was a hit. The ballet won the Australian Dance Award in 2000, was shown on Australian television and turned out to be an audience favourite in the Netherlands, too, on Brandsen’s return to Dutch National Ballet in 2002. Brandsen had found his way to the narrative repertoire, alongside the pure dance works he continued to choreograph. His Carmen was followed by Pulcinella, Coppelia and, in 2016, Mata Hari, which is based on the life of the Frisian woman Margaretha Zelle, alias Mata Hari, who was strong and independent, just like the character of Carmen in the novel, film, opera and ballet.

“I’d been fascinated by Margaretha Zelle for years”, says Brandsen. I like women who don’t conform to the standard image, who depart from the norm and choose their own path, and who therefore often write history. I think Mata Hari belongs in this category, like Madame de Staël, Queen Elizabeth I, Eleanor Roosevelt and Aletta Jacobs, for example”.

The way that Zelle took control of her own life was something he also found exceptionally intriguing. “From her teenage years on, she had many trials to bear. Her father left the family after his shop went bankrupt, her mother died shortly afterwards, she had an unhappy marriage, her son died in mysterious circumstances and then her daughter – the only beautiful thing still left in her life – was also taken from her. Yet none of these events seem to have tamed her huge vitality. Instead of giving up, she continually transformed herself. Every time her role had played itself out, she reinvented herself, as it were, like a Madonna or Lady Gaga avant la lettre. Ordinary real life was too narrow for her, so instead she concocted her own imaginary life and made it even bigger, creating her own reality”.

FAST-FLOWING RIVER

Looking back, says Brandsen, it was no mean feat creating a production about Zelle’s turbulent life. “The big question, of course, was how to tell that fast-flowing river of her life story in dance, and why it should be done in dance at all. How could we do it in a way that couldn’t have been done better some other way? It was an extremely exciting process”.

The first ‘obstacle’ to overcome in narrative ballet, says Brandsen, is that the audience has to detach themselves from their everyday outlook and their normal frame of reference. “The same goes for opera. You have to create a certain suspension of disbelief, because as soon as people start thinking ‘Good grief, that woman looks weird in those pointe shoes’, it just doesn’t work. I’ve often seen that sort of ballet myself in the past, where everything is portrayed very literally – down to the carpets and tablecloths – like an English costume drama on pointe. But in my view, narrative ballet has to have a certain degree of abstraction, although the audience does have to be able to follow the story, as well as your choreographic approach. It remains an exciting challenge to find the right balance between the two”.

CINEMATIC ‘FLASHES’

In their production, Ted Brandsen, librettist Janine Brogt, composer Tarik O’Regan, costume designer François-Noël Cherpin and set and lighting designers Clement & Sanôu really wanted to express the element of ‘malleability’ that characterised Margaretha Zelle’s life. Brandsen says, “Our production isn’t a historical treatise. It’s not an account of ‘then this happened and then that’, and neither does the performance focus on just one incident or period of her life. So much happened, and she went to so many places and experienced so many dramas. We want to capture that feverish, hectic, faster-than-you-can-keep-up-with train of events. So we opted for a libretto that describes her life in flashes; in a rapid succession of short scenes that follow one another in a cinematic way”.

Brandsen and librettist Janine Brogt talked at length about which ‘key moments’ should be shown. Brandsen says, “For instance, I really wanted to include Mata Hari’s audition for Serge Diaghilev in the production. Even though she wasn’t accepted, she took her dancing very seriously. In the Dutch East Indies, she studied Indonesian dance in great detail, and in Paris she trained for a few hours a day. This link to ‘our’ world (the ballet world – ed.) also made her very interesting to me, of course”. Brandsen laughs, “I could never have made a ballet about Marie Curie, for example”.

So gradually a framework was established, within which Brandsen and Brogt decided which scenes should be elaborated on because they lent themselves well to choreography, and which scenes would be better as transitional fragments. Brandsen says, “But in both cases, there are never scenes that stand alone – they’re all necessary for understanding the storyline well”.

CELEBRATION OF DANCE

Brandsen looks back on the creation process of Mata Hari with ‘a lot of gratitude’. “It was an intense period, in which we were able to work on this new production with great focus. The collaboration with Anna Tsygankova (who danced the role of Mata Hari at the world premiere – ed.) was hugely inspiring, and it was also a gift to work with the other Mata Haris and with the whole group of dancers. At the start, we worked in the studio with an electronic tape of Tarik O’Regans music, and later with a piano score, but the moment when we heard the full orchestration – which was not till the first stage rehearsals – was absolutely fantastic. Seeing everything come together – dancers, sets, costumes and orchestra – was a very special experience”.

He says it feels just as special to be reviving the production now. “First of all, we’ve got three new Mata Haris and many new men who dance the roles of her lovers. So we have to get all these dancers prepared for their important roles, which makes the rehearsal process exciting and challenging”.

“In addition, this is the first big production we’ve presented since the outbreak of the corona pandemic. Nearly the whole company – around seventy dancers – will soon be on stage together, and there are also around seventy musicians in the orchestra pit. It’s almost unreal. The ballet masters come to me in disbelief, saying, ‘Will I really soon be taking a rehearsal with 57 dancers?’. But at the same time, it’s all very familiar. After working in small groups for a long time, it’s wonderful that everyone – dancers, musicians and staff – is together again and involved in a production. I see it as a celebration of our art form; a celebration of what everyone in Dutch National Opera & Ballet stands for – from the costume department to the lighting team, and from the props department to the stagehands. I’m so happy we’re back again and so grateful for all the support we’ve received from our audiences and from the government. I really hope our audiences return to the theatre and that the dancers can once again perform to full houses”.

Over the past five years, his view of Mata Hari has been confirmed, rather than changed. “If people had any idea at all beforehand about Mata Hari, it was usually an image of a sultry, wicked, cunning person: a heartless predatory female and a shrewd spy. But that’s not how we wanted to portray her in our production. For us, she was more a victim of her situation: it was wartime, things were bad in France, people needed a scapegoat and they found one in this former celebrity and sexually liberated woman, who behaved differently to what was expected of women in those days. In 2017, on the commemoration of the centenary of her death, many previously inaccessible archives were opened up, which actually confirmed and endorsed the image we had sketched in our production. So my interest in her has not diminished in the slightest. She wasn’t a ‘villain’; she was someone who took every opportunity to survive and make something of her life, despite all the setbacks. Every time something went wrong and she was kicked down for the umpteenth time, she just climbed back up again”.

Text: Astrid van Leeuwen