Mahagonny: anti-opera or classic?

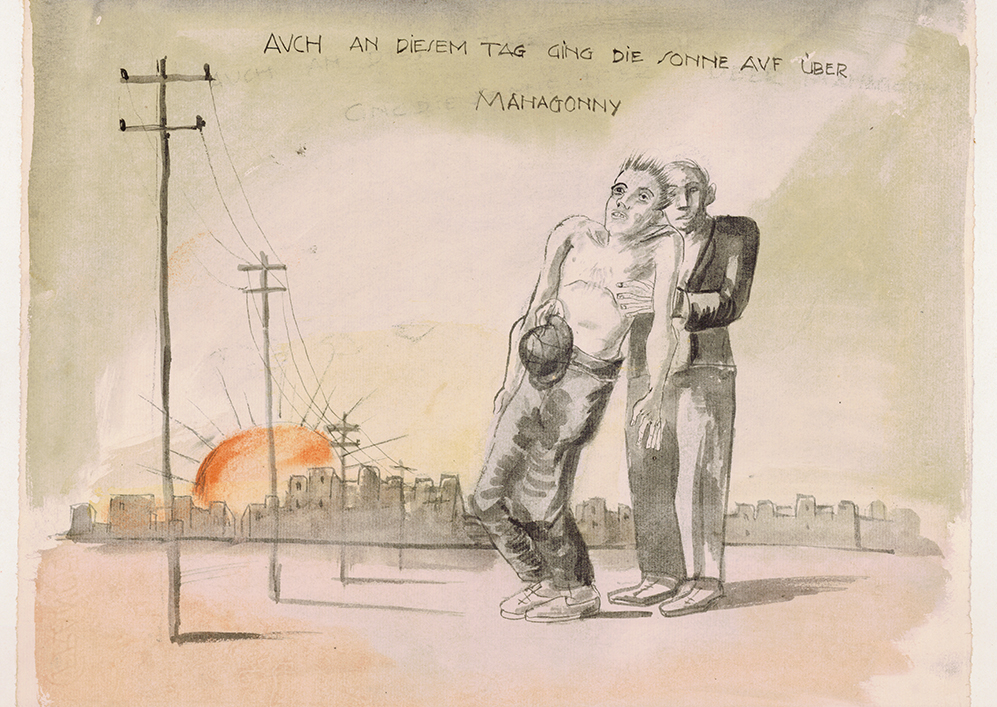

In 1927, the composer Kurt Weill wrote a short work of music theatre based on a series of poems Bertolt Brecht had penned about the fictional city of Mahagonny. Encouraged by the result, Weill and Brecht decided to develop the concept further into a full-length opera.

Text: Wout van Tongeren

That work, Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny, can be seen in a way as an anti-opera, in which the two left-wing thirty-somethings Weill and Brecht incorporated biting criticism of the antiquated opera business. But there is something parasitic about Mahagonny as an opera that criticises opera. Brecht and Weill deliberately wrote their anti-bourgeois work for the established circuit of opera houses, and they deployed distinctive elements of the genre precisely to highlight the tradition’s limitations and create room for an alternative. This attempt to shake up the world of opera demanded courage, not just from Weill and Brecht but also from the opera houses that included the work in their programmes.

The most vehement reactions to Weill and Brecht’s so-called ‘cultural Bolshevism’ came from conservatives and far right groups. The world premiere in Leipzig in March 1930 was disrupted by protests orchestrated by supporters of Hitler’s NSDAP. The opera was soon pulled from the programme. In other German cities too, performances of the opera sparked riots. Mahagonny’s biggest success was in a production in Berlin at the end of 1931, which ran for fifty consecutive nights. That run came to an end in 1932, the year in which the NSDAP became the largest party in the German parliament. In the months that followed, the situation in Germany became so intolerable for Brecht and Weill (who was Jewish) that they felt forced to flee their home country.

In the decades following the Second World War, there were new productions of the opera in Germany and elsewhere. Now, with dozens of productions in over twenty countries since the year 2000, Mahagonny is fast becoming a fixture in the established repertoire. But what does it mean when a work that was conceived as a criticism of the genre becomes part of the operatic canon? Does Mahagonny still have the power to disrupt, to strike a critical note?

Gratification of desires

Weill was convinced that the opera of his day had become isolated. He felt it should do more to appeal to a broader public. And it should be open to influences from society, not in a superficial way but down to its core and deep within its musical structure. Brecht was even more radical: he was not sure opera had any future at all. In his view, the operatic practice of the day with its focus on visual and musical entertainment served an outmoded social system. It might survive for some time yet, but both capitalist society and the associated world of opera were obsolete and untenable in the long run. Indeed, Brecht and Weill’s decision to make ‘pleasure’ the subject of their production was intended as a criticism of the vacuous culture of opera devoted purely to sensory delight.

The story is told with big jumps in the narrative, featuring characters who all seem somewhat off-beat and are difficult to empathise with. That is deliberate. Brecht and Weill did not want audiences to be caught up in the story; instead, they were meant to reflect critically on the subject matter from a certain distance. The opera recounts the history of the city of Mahagonny, founded to give people (men above all) the opportunity to indulge their desires in return for their cash. It is a society that revolves around consumerismn, a place where meaningful work no longer exists. After some early problems, the city hits upon its golden rule: anything goes as long as you can pay for it. That is fine until one of the inhabitants, Jim, runs out of money. He immediately loses all his rights. His death sentence for being penniless ushers in the city’s decline. Jim’s fall reveals the absence of any social cohesion or meaningfulness in Mahagonny, exposing the design flaw in the city’s social underpinnings.

The gratification of desires can never be the ultimate goal because it knows no end — there is always something new to enjoy. When enjoyment is all that matters, only something external can bring it to an end; in Jim’s case that is the point at which his wallet is empty. Jim seems to realise this shortly before his execution: “The pleasure I bought was no pleasure, the freedom I bought no freedom. I ate and wasn’t full, I drank and got thirsty.” Mahagonny descends into chaos. Prices rise, the population fragments into competing groups marching in protest and the city burns to the ground.

Divergent music theatre

Weill was aware he was composing his opera at a time when radio, gramophone records and dance halls had created a new musical landscape. Indeed, he drew from contemporary ‘light music’ such as jazz, schlager songs and popular dances for his own music, while at the same time using composition techniques from the classical tradition. The composition plays with kitsch effects and includes numerous stylistic references, but it is more than simply an amusing dalliance with forms: Weill wanted to create a modern kind of opera. To do that, he reverted to the structure of the ‘number opera’, an older form that had been rejected by influential figures such as Wagner and Verdi.

In Weill’s modern take on the number opera, the various arias and ensembles are composed as more or less independent songs. The music does not serve to propel the action forward or engender an emotional response in the audience, but instead signals the meaning of that moment — seduction, conflict, show — often fairly emphatically. Both text and music are designed to let the opera communicate directly with the audience: the sentences are simple and forthright, the vocal lines contain little ornamentation and they follow the natural melody of the words.

It is striking how this opera, like Dreigroschenoper and Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess, has resonated with the same popular culture from which the composer drew inspiration. ‘Alabama Song’ has become particularly well known after being covered by David Bowie and The Doors, among others. The way in which elements of the opera have lived on beyond their original context reflects Mahagonny’s open character. In contrast to Wagner’s ideal of a Gesamtkunstwerk in which music, text and image fuse to form a grandiose, carefully crafted whole, Brecht and Weill created a divergent form of music theatre in which the narrative progresses in leaps and bounds, the spectator’s attention is deliberately scrambled and the text, music and images remain recognisably separate elements.

In short, Weill and Brecht came up with a serious alternative in their attempt to shake up the opera world. Mahagonny may contain polemical and ironic elements but it genuinely does offer an alternative, constructive form of opera. That is precisely why the work has survived beyond the circumstances of its origins and become part of the repertoire.

Mahagonny as a classic

Director Ivo van Hove’s production of Mahagonny, presented by DNO, essentially treats it as a repertoire opera. For example, the performances are in the original German, which in a production for a Dutch audience undermines the directness of the texts as intended by Weill and Brecht to some extent. Conceptually, the stage direction is historically informed and uses the opera’s potential for social criticism to say something about society today — but in that sense the approach is no different to that taken with many other classics of the operatic repertoire. There is certainly no question of an attack on the modern opera establishment — could we even expect this from an opera created ninety-three years ago? On the contrary, the production is a reminder that the world of opera has in fact been able to absorb what were once radical innovations. In short, there is little that is shocking for modern audiences in this Mahagonny.

‘It turns out that Brecht and Weill’s cynical interwar utopia is surprisingly topical’

However, by treating Mahagonny as a repertoire work, the production demonstrates one of the strengths of our operatic culture, namely its ability to reflect on our world today in a dialogue with works that were created in a different time. It turns out that Brecht and Weill’s cynical interwar utopia is surprisingly topical. It could be argued that our society is more dominated than ever by the gratification of desires. Equally, Mahagonny could be seen as a parable of the dubious triumph of neoliberalism in the decades following the fall of the Berlin Wall. Mahagonny’s social criticism continues to bite, but whereas the opera originally also constituted a self-referential criticism of the medium of opera, other media now seem better equipped for such medium criticism — as Van Hove and his team seem to suggest with the decision to locate the story on a film set. Indeed, it is the world of film and television, mediated by cameras, that seems particularly driven by the pleasure economy, or even to be spurring it on. As the philosopher Slavoj Žižek writes, “Cinema doesn’t give you what you desire, it tells you how to desire”. But what about the internet, where satisfying desires has become a billion-dollar industry? Could the story of the city of Mahagonny — whose name means ‘city of nets’, we are told in the opera — also be interpreted as a story of the rise and moral decline of the worldwide web?

BERTOLT BRECHT ON OPERA

“The question needs to be asked now as to whether opera has not already reached a state in which further novelties no longer reinvigorate the genre but merely lead to its destruction.”

Bertolt Brecht – “Anmerkungen zur Oper Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny” (1930)

KURT WEILL ON OPERA

“Opera should focus on the interests of a broad public, which will need to become its target audience in the near future if it wants to retain any kind of raison d’être.”

Kurt Weill - Antwort auf die Rundfrage: “Wie denken Sie über die zeitgemäße Weiterentwicklung der Oper?” (1927/1928)

Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny is to be seen at Dutch National Opera & Ballet from 6 to 27 September 2023