Momentum for Majoie Hajary

An interview with Maarten van Hinte and Ellen de Vries

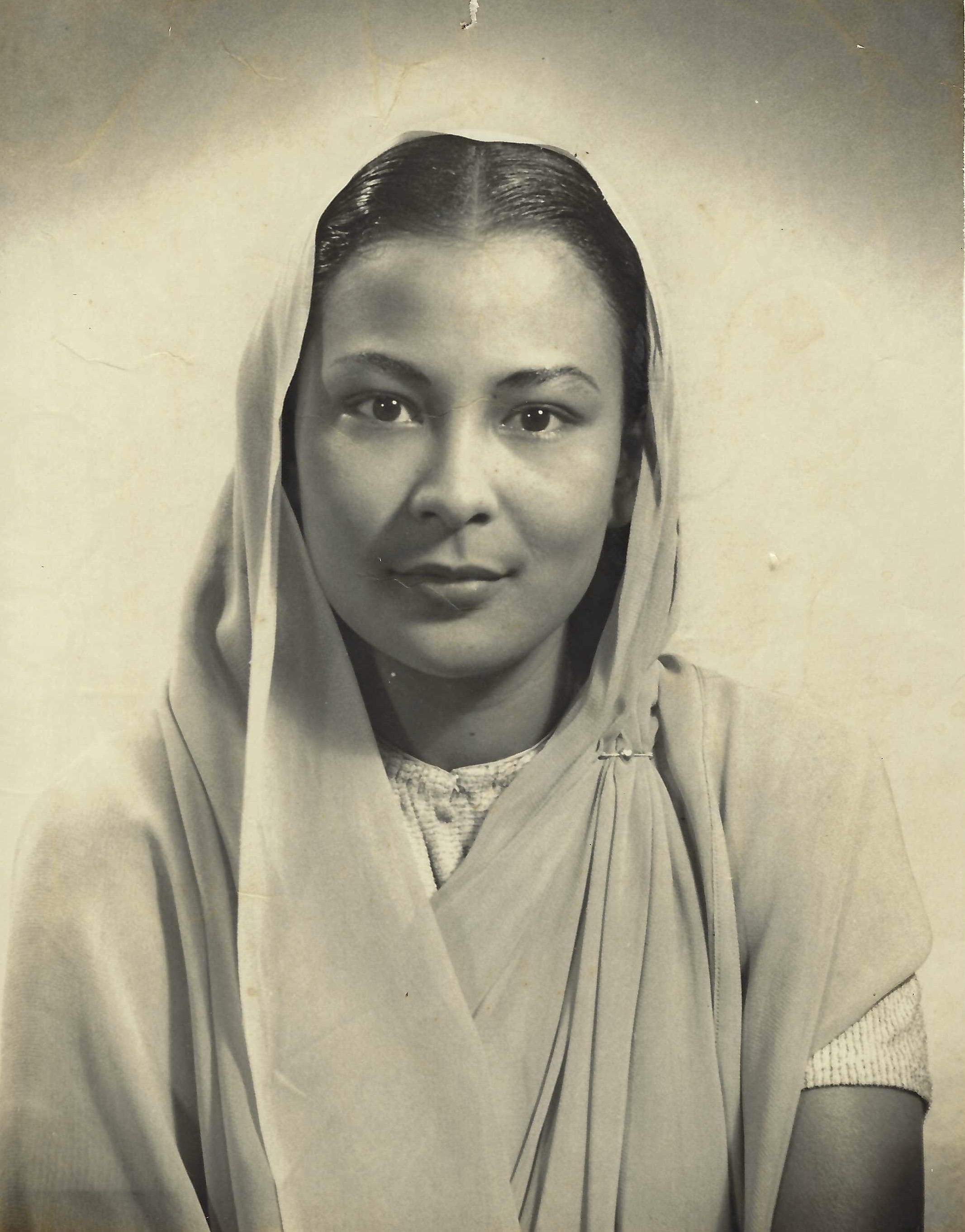

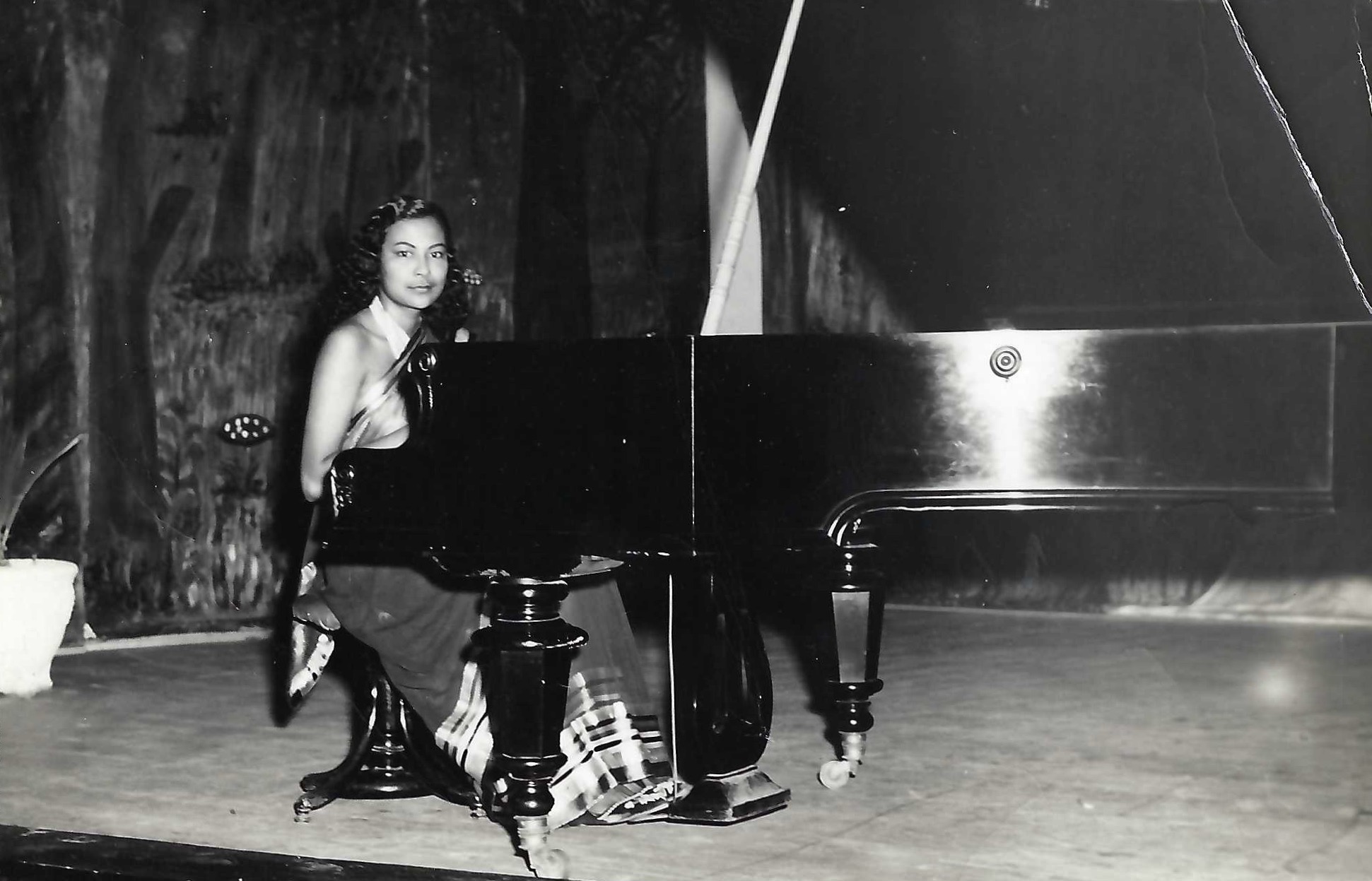

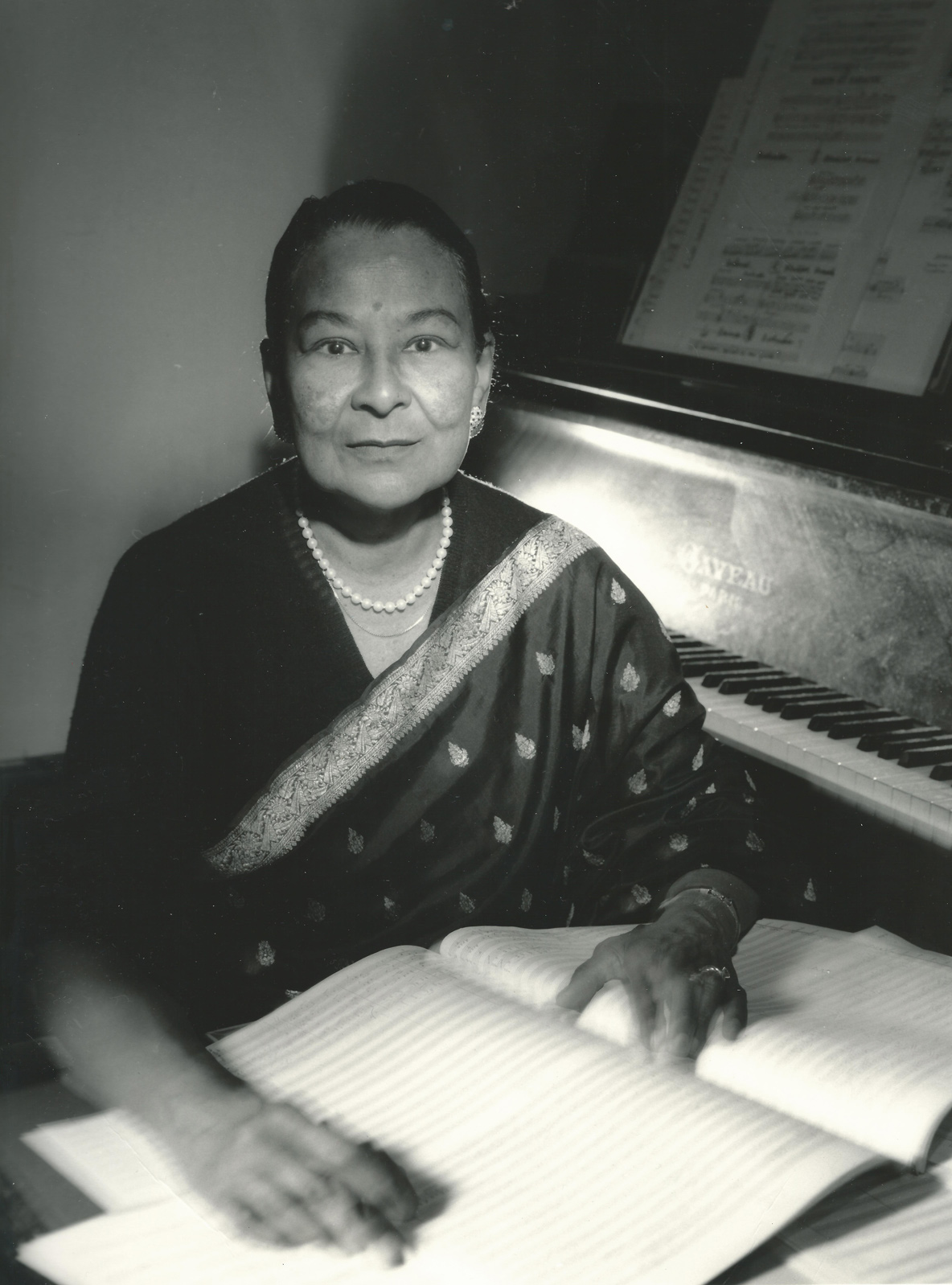

‘A composer is only appreciated when he or she is dead’. That is what pianist and composer Majoie Hajary (1921-2017) said in a 1972 interview. She personally provided the proof for this theory: it was not until after her death in 2017 that she slowly started to rise to fame. ‘Her time is now,’ says Maarten van Hinte, who will lead the panel discussion at Dutch National Opera’s Blue Raga foyer evening about Majoie Hajary on 22 October. We sat down with Van Hinte and Hajary’s biographer Ellen de Vries to talk about this exceptional artist.

Majoie Hajary was born in Paramaribo, Suriname, in 1921, the daughter of an Indo-Surinamese father and an Afro-Surinamese-Chinese mother. She left Suriname as a teenager to study piano and composition at the Amsterdam Conservatoire of Music. She went on to study with Nadia Boulanger in Paris, among others, and blossomed into a sought-after concert pianist. Although she never lived in Suriname as an adult, and reverted to Dutch nationality after having been a French national for a while, she cherished her ties with Suriname throughout her life, both in her heart and in the works she composed. This is illustrated by her grand, but never completed, opera La larme d’or (The golden tear) about Suriname’s colonial history.

In awe

Maarten van Hinte met Majoie Hajary at her home in France when he was a little boy. What he remembers most of all is how in awe he was of Hajary. ‘My family and I lived in France for a while when I was young, as did Majoie at that time. My mother knew her from Paramaribo, mostly because my aunt was friends with her and studied in the Netherlands at the same time as Majoie. When my mother went to visit Majoie at some point, she brought me with her. I remember Majoie as very elegant and refined, a truly sophisticated lady and a woman of the world. She was a Surinamese lady who was married to a member of the French elite – that in itself was remarkable at the time and it definitely made an impression. It was awe-inspiring how she moved between those worlds and managed to connect them.’

It was Van Hinte’s mother who told him that Hajary was not just a pianist, but a composer too. ‘My mother was well-aware that Majoie was underrated and said: “people underestimate who she is.” That’s something I’ve always remembered.’

Musical influences

Another person who was surprised that Majoie Hajary has remained under the radar until now is writer and researcher Ellen de Vries, whose biography of Hajary will be published in lbate 2024. ‘I had heard of Majoie from some Surinamese friends of mine, but I didn’t know much about her when I was contacted by her niece Chandra van Binnendijk, who was working on a biography of Majoie with a colleague. Personal circumstances prevented Chandra from completing the biography and she asked me to take over. That’s when I took a deep-dive into her life. It was bizarre to me that Majoie was such an unknown entity, even in Suriname. Her music is truly exceptional and surprising. It’s definitively deserving of a wider audience.’

What makes Hajary’s music so special in De Vries’s opinion are the cultural and musical influences that are reflected in her compositions. ‘She mixed classical music with music from Asia – she spent some time in Japan – and from the African countries where she lived, as well as blending in jazz elements. Her body of work isn’t all that large, but she constantly came up with new arrangements for different instruments, giving her works a new spin time and again.’

Since Hajary lived and performed in so many places during her lifetime, De Vries’s research took her all over the world. De Vries: ‘I went to Suriname, of course, to find people who might be able to tell me about Majoie. I discovered that it was mostly the older generation that knew her and saw her performances, such as her oratorio Da Pinawiki (The passion week – ed.) in the 1970s. But I also had the website about Majoie translated into different languages, in hopes of hearing from people all over the world and perhaps uncovering new recordings of her work. That would help answer the question of how we view Majoie’s music today and what place she deserves in the canon of music.’

Universal story

‘Her time is now.’ That is Van Hinte’s answer to this question. ‘The history of Suriname – and basically that of the entire Caribbean – has long been oversimplified. It isn’t until now that people are starting to recognise the value of the country’s diversity and the effect it’s had on the rest of the world. Majoie saw her childhood in Suriname as a gift that fuelled her curiosity about many different cultures. In her works – and in her opera La larme d’or in particular – she expresses her commitment to the story of Suriname and her belief that the richness of the country’s diversity is meaningful enough to warrant the making of an opera. That’s why her message resonates, especially in this day and age. It’s an impactful message, also for the Netherlands, where the value of a diverse society didn’t really sink in until about 30 years ago.’

‘I’d like to add,’ De Vries says, ‘that Hajary wrote an opera about Surinamese heroes such as Boni (a Surinamese freedom fighter (1730-1793) – ed.) as early as in the 1980s, even before La larme d’or. Many of these revolutionaries are only now getting their moment in the sun, for instance by being featured in musicals. She was way ahead of her time in that sense as well. What’s more, she wrote the libretto in different languages, which tells you that she had great ambition.’

Van Hinte: ‘It’s these international ambitions that show us how Majoie felt about the history of Suriname. She believed it to be just as important to her own community as to the world at large, expressing through her work that Suriname’s history tells a universal story with universal heroes such as Boni. In short, it’s safe to say that her work was a political statement.’

Source of inspiration

Besides a way to reflect upon society as it exists today, Van Hinte and De Vries believe that Hajary’s work can also serve as a source of inspiration to a new generation of artists. Van Hinte: ‘The narrative tends to be that classical music is created by white people, but that’s not true. It hasn’t been for a long time. The fact that Majoie’s work is now in the spotlight is bound to be inspirational to young artists, particularly to those of Surinamese descent, because it shows them that classical music may have its origins in the Western world, but no one is excluded from writing or playing it.’

‘Over the past few months, Majoie’s works have been performed relatively often, by musicians of different ages and different ethnicities,’ De Vries adds. ‘Including by young Surinamese countertenor Arturo den Hartog (who will also be performing at the Blue Raga foyer evening – ed.). That’s your proof that Majoie is striking a chord and that she’s being discovered by a wider audience.’

Blue Raga

On 22 October, Dutch National Opera presents the foyer evening Blue Raga foyer evening will be held on 22 October. One of the highlights of this event will be Van Hinte’s interview with Ellen de Vries about Majoie Hajary, her body of work and her opera Le larme d’or in particular. Fragments from the opera, including Blue Raga, will also be performed. Van Hinte: ‘It’s going to be an exciting evening. We’ve asked artists with a background in classical music as well as artists from outside the classical world to reflect upon Majoie and her work. Together with them, we will explore how her work was influenced, for instance by Indian music and traditional maroon music. Most of the audience will probably know little about Majoie, so we see it as an opportunity to introduce her to them.’ The evening could also be an opportunity to find new sources about Hajary. De Vries: ‘Musicians have different networks than writers do, so if we’re lucky we might stumble across a few recordings we don’t know about yet. I’m hoping for a bit of a snowball effect.’

And how they want the audience to feel at the end of the evening? Van Hinte and De Vries have the same one-word answer to this question: ‘inspired.’

Text: Rosalie Overing