Forsythe

Performance information

Voorstellingsinformatie

Performance information

The Vertiginous Thrill of Exactitude

Choreography

William Forsythe

Music

Franz Schubert – Allegro vivace from Symphony No. 9 in C-Major

Set design

William Forsythe

Costume design

Stephen Galloway

Lighting design

William Forsythe

Staging

José Carlos Blanco

Ballet master

Larissa Lezhnina

World premiere

20 January 1996, Ballett Frankfurt, Oper Frankfurt, Frankfurt

Premiere with Dutch National Ballet

31 August 2001, Dutch National Opera & Ballet, Amsterdam

Duration

circa 11 minutes

Pas/Parts 2018

Choreography

William Forsythe

Music

Thom Willems – Pas/Parts (on tape)

Set design

William Forsythe

Costume design

Stephen Galloway

Lighting design

William Forsythe

Staging

Amy Raymond

Ballet masters

Guillaume Graffin

Judy Maelor Thomas

World premiere Pas/Parts

31 March 1999, Ballet de l'Opéra national de Paris, Palais Garnier, Paris

World premiere Pas/Parts 2018

9 March 2018, Boston Ballet, Boston Opera House, Boston

Premiere Pas/Parts 2018 with Dutch National Ballet

14 June 2019, Dutch National Opera & Ballet, Amsterdam

Duration

circa 36 minutes

Blake Works I

Choreography

William Forsythe

Music

James Blake – I Need A Forest Fire, Put That Away And Talk To Me, The Colour in Anything, I Hope My Life, Waves Know Shores, Two Men Down and f.o.r.e.v.e.r. from the album The Colour in Anything (2016)*

Set design

William Forsythe

Costume design

Dorothee Merg

William Forsythe

Lighting design

Tanja Rühl

Sound design

Niels Lanz

Staging

Stefanie Arndt

Ayman Harper

José Carlos Blanco

Ballet masters

Charlotte Chapellier

Guillaume Graffin

Sandrine Leroy

World premiere

4 July 2016, Ballet de l’Opéra national de Paris, Palais Garnier, Paris

Premiere with Dutch National Ballet

10 June 2023, Dutch National Opera & Ballet, Amsterdam

Duration

circa 30 minutes

* I Need A Forest Fire: Written by Justin Deyarmond Edison Vernon. Published by April Base Publishing. Administered by Kobalt Music Publishing Ltd.

Other tracks: (P) 2016 Polydor Ltd. (UK)

Musical accompaniment

Dutch Ballet Orchestra, conducted by Matthew Rowe

Set, lighting and sound

Technical department of Dutch National Opera & Ballet

Production manager

Anu Viheriäranta

Stage managers

Kees Prince

Wolfgang Tietze

Senior carpenter

Wim Kuijper

Senior lighting managers

Michel van Reijn

Angela Leuthold

Lighting supervisor

Wijnand van der Horst

Sound engineer

Florian Jankowski

Costume production The Vertiginous Thrill of Exactitude

Costume department of Dutch National Ballet

Costume production Pas/Parts 2018

Martine Douma and costume department of Dutch National Ballet

Costume production Blake Works I

Costume department of Dutch National Ballet, in collaboration with Klaus Schreck

Assistant costume production

Michelle Cantwell

First dresser

Andrei Brejs

Introductions (in Dutch)

Lin van Ellickhuijsen

Total duration

circa one hour and fifty minutes, including one interval

This production is part of the Holland Festival 2023

Cast sheet

The cast sheet for Forsythe will be posted on this page one day before the performance and will be available until one day after the performance.

Three compositions, countless challenges

This Forsythe programme affords the spectator the unique opportunity to see three clear examples of how choreographer William Forsythe recontextualized classical ballet vocabulary through the lens of diverse musical genres.

Three compositions, countless challenges

Forsythe’s collaboration with Dutch composer Thom Willems, composer of the electronic score for Pas/Parts 2018, has been prolific and their almost 40 years of creative work is understood as a historically significant artistic partnership in the field of ballet. Willems has always challenged the musical establishment with his compositional means, and has brilliantly defined how instrumentation, melody and harmony can be now understood in the era of electronic composition. Creating around 60 works for Forsythe, Willems compositional strategies prefigured that of many contemporary electronic music composers, James Blake – whose work also appears on the programme – included. What singles out Willems and Blake is that their compositional roots lie in their classical musical education. Like Forsythe, they investigate how academic rules might operate in a non-traditional environment. Whereas Willems acoustic scale could frequently be equated with the orchestral or symphonic, Blake has primarily applied his skills to the field of song writing. Though each composer has unique acoustic palettes, both composers imbed their idiosyncratic ‘instrumental’ sounds in dense structures that are grounded in traditional techniques.

The challenges are unique in the case of each composer. Willems has frequently proposed works with disrupted time signatures, which often present onerous demands on the dancers who must commit his music to memory. At the same time, his rhythmical fragmentation upended the logic of vocabulary choices for Forsythe, who felt compelled to keep the kinetic logic of ballet’s traditional movements intact (and this logic is always linked to a certain rhythmicity). Willems’ persistant challenges ultimately allowed for the emergence of an entirely new genre of ballet.

Blake Works I is a different story. Practicing within the popular musical idiom, James Blake most frequently uses the straightforward time signatures associated with the pop genre. What he does within those structures is creating densely syncopated, multilayered rhythmical environments that could actually be compared with some of Tchaikovsky’s most inspired dance instigations. This compositional environment allowed Forsythe to link traditional chains of ballet logic, but in a setting that provided a culturally fresh frame for the spectator to consider traditionally cohesive phrases of ballet vocabulary.

Forsythe’s choreography of The Vertiginous Thrill of Exactitude to music by Franz Schubert is now part of the contemporary classical ballet canon and is an unapologetic homage to the hard-won skills of the dancers, who, aside from their obvious technical command, have over time acquired refined ears for orchestral nuance. Schubert’s propulsive music provided the opportunity for the choreographer and his dancers to cheerfully examine the nineteenth century ‘Divertissement’ genre. However, this example adheres to rhythmical subdivisions of Schubert’s oeuvre that create an almost superhuman demand for the dancer. Their capacity to ‘hear’ the choreography’s voice, which jumps from instrument to instrument at an alarming rate, is one of the works most onerous aspects. The precariousness of this task is what the audience and the dancers both experience at the same time, and the resulting elation at the ballet’s conclusion is an affirmation of the vital, supportive community that can be created during a live performance.

Text: Nathaniel Miller

Ballet stripped to the bone

Follow the link below to read more about the great significance of William Forsythe.

Ballet stripped to the bone

William Forsythe is regarded as the most radical and influential dance innovator of the past fifty years. Dutch National Ballet now has seven of his groundbreaking ballets in its repertoire, and is paying tribute to the American master choreographer in Forsythe. The programme includes the Dutch premiere of the company’s eighth acquisition: Blake Works I.

His ‘artistic father’. That is how William Forsythe (New York, 1949) sees the Russian-American choreographer George Balanchine (1904-1983), who preceded him as the greatest innovator of the art of ballet. It may or may not be a coincidence that Ballett Frankfurt first danced a work by Forsythe in 1983, the year of Balanchine’s death. The title, Gänge – ein Stück über Ballett, would soon turn out to be significant. Forsythe was to analyse his ‘mother tongue’ down to the last tiny detail. Like Balanchine before him, he would shake up and enrich classical ballet, although in a totally different way.

Prising free and shaking up

Balanchine’s contribution was huge. He stripped ballet of its narrative character and gave it fresh vitality, adding enormous dynamism, swing and sharpness. However, he did remain true to the structure and rules of classical ballet as laid down at the court of Louis XIV.

Forsythe, on the other hand, expressly questioned the ‘laws of ballet’. Systematically, he began to prise free and shake up the frontal presentation, symmetry and entrenched logic of balletic syntax. He exposed the underlying system of classical ballet and stripped it to the bone, including its relationship to the audience.

Euphoric

Forsythe made his international breakthrough with Artifact in 1984. Anyone who saw it at the Holland Festival in 1987 will surely remember the euphoric mood that pervaded the foyers of Dutch National Opera & Ballet in the intervals. With great aplomb, Forsythe had ushered traditional ballet into the realm of contemporary art. The classical lines became quirky, balances were way off the perpendicular, arms and legs were stretched to their maximum extension and new composition strategies broke open and rearranged standard combinations of steps, whether or not according to algorithmic calculation models or philosophical treatises.

Leading companies

In the years that followed Artifact, Forsythe created groundbreaking works for Ballett Frankfurt, where he was artistic director for 20 years. While his classically oriented ballets were in demand at leading ballet companies all over the world, Forsythe’s work with his own company gradually shifted towards a more hybrid form of dance theatre. Many of these unique investigations were based exclusively on the artists upon whom they were created and were not to be reproduced by any other companies.

Back to ballet

After the closure of Ballett Frankfurt, his novel investigations continued with the more compact The Forsythe Company from 2005 until 2015. Since then, his interest in classical ballet has been rekindled. As a freelance choreographer, he has recently created new ballets for Ballet de l’Opéra national de Paris (including Blake Works I, which will have its Dutch premiere in Forsythe), as well as for English National Ballet, Boston Ballet and the Balletto del Teatro alla Scala in Milan. The American ‘boy wonder’ may have reached the age of 73, but his creations continue to challenge dancers, amaze audiences and inspire new generations of choreographers.

Text: Astrid van Leeuwen

Translation: Susan Pond

‘Even my dachshunds bark along’

Follow the link below to read an interview with composer Thom Willems.

‘Even my dachshunds bark along’

Composer Thom Willems worked with William Forsythe for thirty years. In that period, he wrote over sixty works for the choreographer. The secret of their collaboration was, says Willems, mutual respect and understanding. “We always managed to find solutions for each other’s ideas.” For Pas/Parts, one of the three ballets in this Forsythe programme, Willems pulled out all the stops. “I wanted to make twenty totally new ‘musics’. The minute one of the sections made the slightest reference to what we already knew, I threw it out straight away.”

Gänge. In 1983, that was the first revolutionary work by William Forsythe that Thom Willems saw, performed by Nederlands Dans Theater. Willems says, “Here was someone who clearly showed incredible nerve in tackling boundaries and daring to set new standards. What he did was unprecedented. Spectacular to watch. So I immediately thought ‘now there’s an interesting man!’”

At the time, Willems (1955, Arnhem) was still studying at the Royal Conservatoire in The Hague: composition with Louis Andriessen and electronic music with Jan Boerman and Dick Raaijmakers, the Dutch pioneers in this field. “Electronic music as we know it today didn’t really exist back then. There were no computers or synthesizers as yet. À la Jan Boerman, I was mainly cutting and duplicating tapes. Using the most diverse materials, we created sounds – rhythm was still much less important – and I really loved doing that. More than writing notes.”

Deeply impressed by Gänge, Willems approached Forsythe, who responded ‘very amenably’. “We dived into the studio together and afterwards he said, ‘I’ll see if I can involve you in one of my next pieces’.” Not much later, Forsythe was appointed artistic director of Ballett Frankfurt, and shortly afterwards Willems got his first commission. “We had to get a production off the ground in three months: LDC. Nowadays, I wouldn’t dare, but then I had the guts to say ‘yes’ straight away.”

‘You could never be lazy’

After having written around sixty compositions for Forsythe, Willems says that ‘continually having to reinvent yourself’ was the biggest challenge of their collaboration, which lasted over thirty years. “Especially in the nineties, things moved fast. In those days, it was premiere after premiere after premiere. It was exhausting, because you had to keep on changing yourself; improving or deteriorating, or whatever. Otherwise, we’d never have stuck it out together so long. Every time, a new constellation or a new concept had to be thought up. Either rhythmical, or just sound, or maybe almost silence. That also made the collaboration so stimulating. You could never be lazy!”

The creative process varied continually as well. Sometimes the dance came first, and sometimes the music, and often the two were created more or less simultaneously. “For The Second Detail, for example, Bill (William – ed.) was working in Toronto and I was in the music studio in Frankfurt, and every evening a tape was sent with Lufthansa to be picked up by someone from The National Ballet of Canada. And whenever I’d delivered something, there was immediate contact and Bill said, ‘Think about this, or do more of that’, or ‘fantastic, keep on like that’, or ‘could I have more of this?’”

There wasn’t a great deal of discussion prior to a new creation. “Bill showed me things he was working on, and I let him listen to things I was doing. There certainly weren’t any endless conceptual discussions. Often, we just exchanged ideas briefly in the kitchen, or during meals, and then the outlines for a new work would be established in a single evening. One of us said this, and the other said that. In that way, we complemented each other and the ideas and concepts grew, and the process was always remarkably easy.” And there was great mutual respect and understanding. “We always managed to find solutions for each other’s ideas. I for his choreography, and he for my music. The brain cells got down to work. When I worked with other choreographers, I had to give more explanation, but with him long discussions were unnecessary. You see what someone’s doing and you try to understand it, and then you put it into music, or into dance.”

In opposition

Pas/Parts was the second big commission Forsythe and Willems received from the prestigious Ballet de l’Opéra national de Paris. “Twelve years before, in 1987, we’d made In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated for the company. That piece begins with a loud bang – crash – and then the music goes on for 28 minutes at the same rapid tempo: shhh shhh shoo, shhh shhh shoo, shhh shhh shoo. It’s the tempo of a really brisk walk, like many of the tempi in Stravinsky’s ballets. But as a composer, you keep trying to find oppositions to yourself, of course, so when Pas/Parts was commissioned, I thought, ‘now let’s try to make twenty or thirty “musics” each lasting one to two minutes, which apart from differing widely are all totally unique as well’. That became my task, so if one of the sections made the slightest reference to what we already knew, I threw it out straight away. So musically speaking, Pas/Parts is rather peculiar, in a nice sort of way, as it arises from that idea of ‘Does it sound familiar? Out with it, don’t do it! The way it should be is the way it shouldn’t be!’” A second source of inspiration for Pas/Parts was the advent of the great, world-famous DJs at the end of the nineties. “Those DJs can do one thing, and that’s pinch someone else’s sample and repeat it endlessly, stirring the whole thing up into an ecstasy for a pill-swallowing audience. From ecstasy to ecstasy to ecstasy. So my idea was to also work with samples and repeat them on end, but then to see if we could do more with them than just stir up ecstasies.”

Unprecedented music

All in all, says Willems, this led to the most curious solutions. “And yes, of course it caused quite a bit of excitement. Even my dachshunds – Blinkie Palermo and Puzzel van Ravensburg – bark along at a certain point. But there’s one section I’m personally very fond of: it consists of only extremely low sounds, which was unprecedented music, especially for a theatre like Paris Opera. And as the cherry on top of the cake, Pas/Parts then ends with familiar music, namely a cha cha cha. So we land on safe ground after all and everyone can sigh with relief, ‘Aha, something we know!’”

As soon as he’d got the collection of ‘musics’ ready, he went to Paris, where Forsythe was already at work with the dancers. “Then we decided on the order of the fragments on the spot and put the piece together. Based on the dance and the music, you go in search of solutions and a dramaturgy that works: what’s the structure of the piece, what’s the development, and how does it end, in a way that actually makes sense.” For Willems, the magic of Pas/Parts lies in the element of surprise, both musically and choreographically speaking. “Bill gave me some nice surprises in a few sections.”

Up to here and no further

Pas/Parts, in 1999, was the last big classical production Forsythe created for the time being. After that, he started concentrating on experimental, theatrical works, particularly after founding The Forsythe Company in 2005. That also had consequences for Willems’ involvement. “Bill went in a different direction, and then you arrive at different musical solutions as well. To save on the costs of a music studio, I also started creating more on the spot and playing live myself, in the studio with the dancers and surrounded by an array of synthesizers. I thought that was great. If there’s one thing I enjoy, it’s improvising. And of course it worked really well with that adventurous group of dancers.”

In 2015, The Forsythe Company ceased to exist. “Bill took a different path, and I took a different path too. It was done. And after years of just working and touring, I really needed a break. Added to that, what else can you invent after sixty or seventy ballets? What new standards can you set and which taboos are still left to break down? When you start something – like the collaboration with Bill – it’s a complex tangle. Then you develop and work on the knots, and after thirty years you find you’ve unravelled it all.”

Ravel’s Boléro

Willems is now working on his first opera, about the art of painting, which he is composing on commission from a visual artist in Berlin. “That’s the next big project, and it’s deman- ding all my attention for the moment. I don’t know yet when the premiere will be, but the work already has a title that I really like: Het gewicht van licht (The weight of light).”

Something else he’s been doing in recent years is studying music again. “Over the past thirty years, I didn’t have time for that, but during the corona period I immersed myself in (Maurice – ed.) Ravel, which was a huge revelation. Of course I knew Ravel, but with hindsight I realise my knowledge of his music was superficial. Now I’ve been able to spend two years priming myself and amusing myself with his scores, his ideas and other people’s analyses of his work. Through Ravel, I’ve gained a better understanding of l’objet juste (the sacrosanctity of the melody – ed.).”

Enthusiastically, he talks about an idea he’s recently been airing to anyone who’ll listen. “Ravel’s Boléro was the first conceptual composition in music history, and everyone’s familiar with it. Seven billion people can hum along to the piece. 22 November 2028 is the centenary of the premiere of Boléro. How fitting it would be if every concert hall, opera house and ballet company gave a performance of this ‘international anthem’ on that day – as a tribute to humanity, and of course because it’s sublime music. Nobody is better at musical ‘colouring’ than Ravel.”

Text: Astrid van Leeuwen

Translation: Susan Pond

Three masterpieces by Forsythe

More information on The Vertiginous Thrill of Exactitude, Pas/Parts 2018 and Blake Works l, as well as quotes from some of the dancers.

Three masterpieces by Forsythe

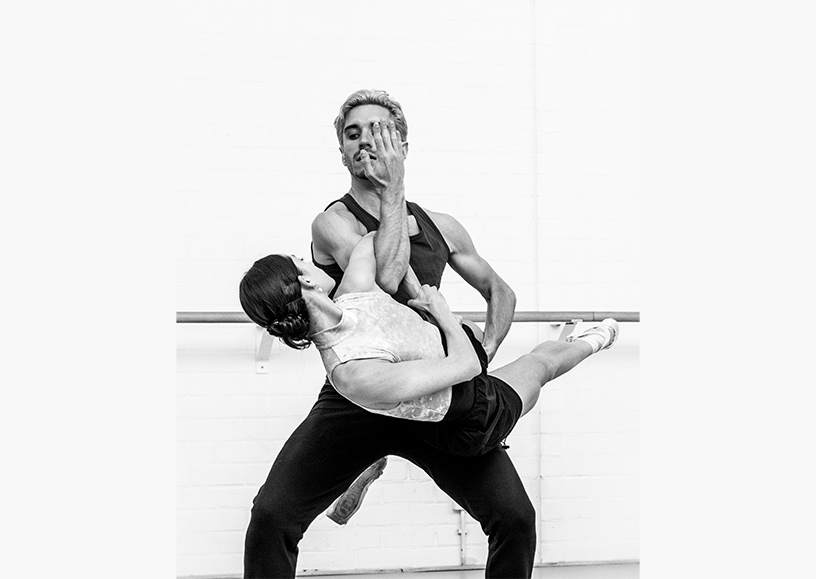

The Vertiginous Thrill of Exactitude

Set to the final movement from Franz Schubert's Symphony No. 9, The Vertiginous Thrill of Exactitude displays all the traditional accoutrements of classical dance: tutus, point shoes, virtuosity, lyricism, and a friendly display of formal manners between the sexes. Originally the last part of Forsythe’s full-length Six Counter Points, the pas de cinq (three women, two men) provides a breathtaking display of classical technique that serves to illustrate the way in which Forsythe sees the ballet vocabulary as part of a range of choreographic possibilities – distilled here to its purest and most brilliant form. An affectionate homage to both Marius Petipa and George Balanchine in its courtly partnering conventions, compositional structure (solo variations set amongst pas de deux, pas de trois and ensemble sections), and speedy, precise allegro work, The Vertiginous Thrill of Exactitude nonetheless belongs utterly to our time in its overt celebration of the dancers' ability to make technical difficulty into a triumph of physical mastery, and in its self-aware embodiment of a whole tradition of dance.

Text: Roslyn Sulcas

“It’s a dream to be able to work with William Forsythe and to dance The Vertiginous Thrill of Exactitude. The special thing about the choreography is that it’s actually both classical and modern ballet. You do very technical, controlled movements on pointe, while your upper body and arms are relatively free. So for me, the piece is about the purity of dance: it shows exactly what a human body is capable of.”

Anna Ol (principal dancer)

“When I’d just joined the Mariinsky Ballet at the age of seventeen, I was allowed to attend a rehearsal of Vertiginous. All I could think was ‘I hope I never have to dance that ballet’, as it looked so difficult! But now I can’t wait. The piece is extremely challenging and musical, and it urges you to push your boundaries – at every moment and in each movement. The fact that I’m no longer afraid of it makes me realise that I’ve really grown as a dancer over the past six years. That makes Vertiginous very special to me!”

Victor Caixeta (principal dancer)

Pas/Parts 2018

Pas/Parts 2018 is the first of two ballets on this Forsythe programme that were originally created for the Ballet de l’Opéra national de Paris. Unsure about the work after the initial performances in 1999, Forsythe put the ballet aside for 17 years only to revive a significantly altered version in a staging for San Francisco Ballet in 2016. Still convinced that work on the difficult score was needed, he consequently produced this iteration of the work for Boston Ballet in 2018.

Pas/Parts 2018 is episodic in structure and each of the nineteen scenes follow each other with mostly abrupt breaks between them. What choreographically binds the work are the thematic threads that weave through the dramatically different musical episodes – the most recognizable of which are the pulsing but static group tableaux of a very formal nature. While these tableaux involve few spacial reconfigurations, the contrapuntal density of arm details gives the structures a baroque feel. That reflection on one hand, on a courtly, stately manner of conduct and the sometimes reckless, impulsive choreographic reactions to Thom Willems coolly chaotic score on the other, lends the work an unpredictable, yet distinctly historical atmosphere.

Anna Tsygankova: “It takes absolute mind concentration to get this choreography in your body. Just learning the steps was a real tour de force. We were bombarded by so much information in the first rehearsals, added to which Forsythe has such a totally unique, special movement style. Once you’ve got the hang of all that, then you have to find the right phrasing of the steps in the music. Whereas that music – or rather soundscape – was a totally alien world to me at the beginning. How was I supposed to find rhythm and timing in music like that? But the more I listened to it, the more I enjoyed it.”

Young Gyu Choi: “Musically speaking, Forsythe’s works are always a challenge. In addition, you need a clean, cast-iron technique to dance Pas/Parts, although you need to find a freedom within that technique. And that’s exactly what makes it so difficult: you have to be both extremely free and extremely precise at the same time.”

Anna: “Once we’d mastered the details of the choreography and the musical phrasing, the répétiteurs told us it was time to take the freedom to put our own personalities into the ballet. So on stage, you have to dare to let go of the great concentration demanded by this work, so that you go into a sort of meditative trance. If you manage to do that, then the complex choreography becomes absolute fun. Young and I each have our own very different roles in the ballet, but actually I’d like to dance all the roles. The boys’ solos are really cool as well.”

Young: “I’d rather stick to my own solo. I really love this role, and now we’re performing the ballet again, I can dance it with even more panache.”

Principal dancers Anna Tsygankova and Young Gyu Choi talk about Pas/Parts 2018

Blake Works I

Blake Works I, staged for the Ballet de l’Opéra national de Paris in 2016, was the first work Forsythe had created in the classical idiom after a hiatus from ballet of more than 17 years. The work is not unlike The Vertiginous Thrill of Exactitude insofar as it deploys a distinctly historical approach to the genre, versus the analytical approach Forsythe had used in the majority of his ballet oriented oeuvre. Blake Works I radiates his affection for the language of ballet, and even revives several iconic fragments from works of the genres great practitioners that had deeply influenced him during his formative years. The work is grounded in the French school and makes use of many of the demanding intricacies of that particular style.

“Right from the start, the rehearsals for Blake Works I were great fun! We often dance to classical music, so this swingy pop music makes a welcome change. It’s also interesting to discover how Forsythe experiments with the boundaries of ballet. All his movements seem to seek out a certain limitation and then exceed it. Yet they remain organic, and they feel very logical for your body. It’s really special to be following in the footsteps of the Parisian dancers – particularly as we can add a bit of our own personality to the choreography as well. That really feels like an honour!”

Elisabeth Tonev (grand sujet)

“Blake Works I is a great deal of fun – but you do have to concentrate hard! Lots of the steps are similar, but just that bit different: the same leg with a different arm, or twice to the left and then once to the right. And they’re choreographed more to words than to counts, so you have to listen well to the singing and not just blindly rely on a simple four-four time. However, it does allow you to play with the dynamics of your movements, which gives you the freedom – within certain limits – for your own interpretation. Blake Works I is a brain-teaser, but a really nice one!”

Jan Spunda (grand sujet)

Programmaboek

BECOME A FRIEND OF DUTCH NATIONAL BALLET

As a Friend you support the dancers and makers of Dutch National Ballet. You are indispensable to them and we are happy to do something in return. For Ballet Friends we organize exclusive activities behind the scenes. You will receive the Friends magazine from us and you will receive priority when ordering tickets.