Swan Lake

Performance information

Voorstellingsinformatie

Performance information

Choreography

Rudi van Dantzig, after Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov

Spanish, Neapolitan and Hungarian dances third act

Toer van Schayk

Music

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky – Swan Lake (1877)

Costume and set design

Toer van Schayk

Lighting design

Jan Hofstra

Artistic supervision

Toer van Schayk

Ballet masters

Rachel Beaujean

Charlotte Chapellier

Caroline Sayo Iura

Sandrine Leroy

Larissa Lezhnina

Judy Maelor Thomas

Guillaume Graffin

Alan Land

Jozef Varga

Musical accompaniment

Dutch Ballet Orchestra conducted by Matthew Rowe

With cooperation of

The students and pupils of the Dutch National Ballet Academy

Rehearsal teacher pupils of the Dutch National Ballet Academy

Dario Elia

Premiere Petipa/Ivanov production

27 January 1895, Mariinsky Theatre, St Petersburg

Premiere Van Dantzig/Van Schayk production

31 March 1988, Dutch National Opera & Ballet, Amsterdam

Duration

circa three hours and twenty minutes, including two intervals

Sets, props, wigs and makeup, lighting and sound

Technical department of Dutch National Opera & Ballet

Production manager

Joshua de Kuyper

Stage managers

Kees Prince

Pieter Heebink

Production supervisor

Mark van Trigt

First carpenter

Wim Kuijper

Lighting managers

Michel van Reijn

Angela Leuthold

Licht supervisor

Wijnand van der Horst

Follow spotters

Titus Franssen

Hein Hazenberg

Lee Hayes

Panos Mitsopoulos

Carola Robert

Anton Shirkin

Marleen van Veen

Follow spotters coordinator

Ariane Kamminga

Sound engineer

Florian Jankowski

Props

Remko Holleboom

Special effects

Peter Visser

Assistant costume production

Michelle Cantwell

First dresser Andrei Brejs

First make-up artist

Trea van Drunen

Orchestra manager

David den Eijlander

Introductions

Klaas Backx

Lin van Ellinckhuijsen

Cast sheet

The cast sheet for Swan Lake will be posted on this page one day before the performance and will be available until one day after the performance.

Synopsis

Follow the link below to read the synopsis of Swan Lake.

Synopsis

Act one

Party in the castle garden

To celebrate Siegfried’s eighteenth birthday, Alexander and the courtiers and neighbours have organized a surprise party for him in the garden of the castle. The Prince’s tutor Von Rasposen is irritated by Siegfried and Alexander’s friendly relationship with the local peasants. The festivities are interrupted by the arrival of the Queen, the Prince’s mother. She presents her son with a ring reminding him of his future role as successor to the throne: he will soon have to choose a bride. Siegfried is downcast at the prospect of his youth drawing to a close. As darkness falls he and Alexander ponder on the future. They decide to explore the surrounding forest.

Act two

The meeting with Odette

Lost in the forest, Siegfried and Alexander arrive at the banks of a great lake. A huge circling bird of prey fills them with fear: it is as if the form of Von Rasposen is still spying on them. The bird of prey – in fact the wicked magician Von Rothbart – summons a swan out of the dark lake, which takes on human form. In Odette, the Swan Queen, and her retinue of swan maidens, Siegfried believes he has found the realisation of his ideals of sincerity and simplicity. Surrounded by these pure shapes he is overcome with joy. He swears to remain forever true to his ideals.

Act three

The betrayal

During a ball at the castle several brides-in-waiting are presented to Siegfried. But to the amazement of the guests, and to his mother’s alarm, Siegfried refuses to make a choice; all the pomp and splendour contrast starkly with the purity of the vision experienced at the lakeside. Von Rasposen announces the last guests: Von Rothbart, his daughter Odile and their retinue. Siegfried imagines that the Black Swan, Odile, is a manifestation of the White Swan Queen, Odette, but still he wavers. Von Rothbart and Odile blind him with a sensual display of dazzling virtuosity. To Alexander’s dismay Siegfried yields and offers Odile the ring. Too late he realizes that he has betrayed his ideal, Odette. Stricken, he flees back to the lake in despair.

Act four

Reconciliation with Odette

Disillusioned and betrayed, Odette and the swan maidens tarry by the moonlit lakeside, where Siegfried finds them. Odette forgives Siegfried and attempts to comfort him, telling him that he must learn to live with reality. Von Rothbart tries to drive Siegfried away from the lake, but although Siegfried manages to defy him, he drowns in the waters. Von Rasposen abandons his futile search for the Prince, while Alexander discovers the lifeless body of his friend. In Alexander, Siegfried’s ideals will live on.

Rudi van Dantzig’s vision of Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake

Rudi van Dantzig (1933-2012) created his production of Swan Lake in 1988 for Dutch National Ballet. In the programme to accompany the first performance series, he gave his notes on the famous classical ballet. You can find a condensed version of these notes by following the link below.

‘He knew he must go’

In reviving Swan Lake – with all respect for Lev Ivanov and Marius Petipa, the choreographers who breathed new life into the ballet in St Petersburg – I took inspiration primarily from Tchaikovsky, in the way he speaks to us through his music and in his letters and diaries. As a composer of ballet music, Tchaikovsky was a revolutionary and a visionary, and was way ahead of his time with regard to the technical restrictions of ballet.

Looking at photos from the time of the tsarist ballet in St Petersburg and Moscow, at the end of the nineteenth century, we see mainly ballerinas whose posture suggests the presence of an extremely restrictive corset, and male dancers who are sturdy gentlemen you’d expect to see in a crowded salon sporting cigars and watch chains, rather than wandering around the edge of a deserted lake.

Tchaikovsky’s music, lyrical and filled with long, melancholy lines, seems far removed from this atmosphere, and to be written for the ballet artists who shortly after his death would raise dance in Russia – and then all over the Western world – to new heights and to its current level: Michel Fokine, Anna Pavlova, Vaslav Nijinsky and their contemporaries. They liberated dance from its straitjacket, the fashionable limitations and pettiness of the time, and fought for the expression of very personal emotions through movement.

What the society of the day expected, and probably what Tchaikovsky expected of himself, was to function as an accepted ‘normal’ human being in that society. However, this did not seem to be Tchaikovsky’s lot, as he was homosexual. The main theme of Swan Lake – the boy who is expected to win a bride and fails – appears to be a direct reflection of Tchaikovsky’s own life.

The main character in Swan Lake, Siegfried, distrusts the worldly knowledge that his tutor Von Rasposen deems so necessary for him. Siegfried believes himself to be close to nature, and feels more drawn to what in his eyes is the uncomplicated lifestyle of the peasants than to the political labyrinth of ranks and positions, machinations, favours and private interests familiar to him from the structured life at court.

The warm tone in which Tchaikovsky writes to his brother Modest, on 16 December 1868, about simple bonds of friendship, is in stark contrast to the letter he writes ten days later about the problem of a possible relationship with the French singer Desirée Artôt. “On the one hand, I love her with all my heart, and at the moment an existence without her seems impossible, but on the other, when I reason with myself coolly and rationally, I can think only of all the possible misfortunes predicted by my friends.”

Resembling a story by Chekhov, an excerpt from a letter written in 1866 is also analogous to a situation in which Siegfried finds himself when confronted by his brides-to-be. “Last night, something really strange happened to me at the Tarnovsky house. I was left alone with three ladies who forced me to waltz with them, one after another, while one of them played piano. I was so exhausted that I had to drag myself home.”

Tchaikovsky’s marriage to the determined music student Antonina Milyukova lasted just a few days. Although it was at least longer than that of Siegfried to Odile, the result was equally catastrophic. The night after the wedding, Tchaikovsky wrote from the train taking the young couple from Moscow to St Petersburg, “I was nearly stifled by suppressed sobs and could have cried out, but I had to keep my wife occupied with conversation until Klin, and only then did I feel justified in remaining behind alone in the dark. My only comfort was that my wife understood or perceived nothing of my barely concealed misery, appearing contented and happy throughout the journey.”

Tchaikovsky died in 1893, at the age of 53. There is controversy about the cause of his death.

“He knew he must go: unafraid, not hesitating, he paused only at the garden's edge where, as though he'd forgotten something, he stopped and looked back at the bloomless, descending blue, at the boy he had left behind.”

This is how Truman Capote ends his novel Other Voices, Other Rooms, and that is how – in my eyes – Siegfried leaves the nocturnal banks of the lake.

Text: Rudi van Dantzig

Translation: Susan Pond

Spectacular virtuosity versus serene fragility

Learn more about the history of the development of ‘the ballet of ballets’ by following the link below.

Spectacular virtuosity versus serene fragility

In composing Swan Lake in 1877, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky gave an artistic impulse to ballet music of the time that should not be underestimated. Yet initially neither his composition nor the corresponding choreography by Julius Reisinger were a big success. It was only after Tchaikovsky’s death in 1893 that the true value of the music was recognised. This led to new choreography by Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov. It is this version from 1895 that forms the basis for today’s continued worldwide success of what is known as ‘the ballet of ballets’.

In a letter to fellow composer Rimsky-Korsakov in 1875, Tchaikovsky wrote, “The theatre director has commissioned me to write the music for the ballet Swan Lake. I’ve accepted the commission, partly because I need the money and partly because I’ve long cherished the wish to have a go at this sort of music.”

So although it is remarkable that Tchaikovsky was interested in the genre – up to then, most ballet music did not rise above the level of mediocre, background sound to create effect – he obviously did see composing for ballet as a challenge. Tchaikovsky liked dancy music – which was also apparent from his other compositions up to then.

Along with the man who commissioned him, Vladimir Petrovich Begichev, who was director of the Imperial Theatres in Moscow, and the dancer Vassily Geltzer, Tchaikovsky adapted Der geraubte Schleier (The Stolen Veil), a German folk tale about enchanted doves, written by Johann Karl August Musäus. But other sources also appear to have been used in writing the libretto, including the Russian folk tale The White Duck. In composing the music, Tchaikovsky is also said to have been inspired by a newspaper article of the day about the worsening insanity of Ludwig II of Bavaria, the king who surrounded himself by swans. The story may have evoked associations with the composer’s own not exactly rose-tinted life.

Far from memorable

The premiere of the first Swan Lake took place at the Bolshoi Theatre, in Moscow, on 20 February 1877 (there are also sources that give the date as 4 March 1877), in a production by the Czech choreographer Julius Wentsel Reisinger. Unfortunately, this mediocre choreographer hardly knew what to do with Tchaikovsky’s music. He had some parts rewritten and supplemented, even adding work by other composers here and there. And various cuts were demanded by the (rather amateur) conductor, so that eventually around a third of the composition was altered.

The Moscow press reacted very negatively to the ballet production. The choreography, the dancers, the sets and the orchestra were all slated. According to the critics, Reisinger’s ballet ‘was completely lacking in imagination and as a whole was far from memorable’. In all the to-do, Tchaikovsky’s composition was pushed aside somewhat. Although some critics did recognise its quality, most found the music ‘too complex’, ‘too Wagnerian’ or ‘too symphonic’. ‘The melody is capricious and moody; not suited to ballet.’

After six years – in which yet more changes were made – Reisinger’s Swan Lake was taken off the repertoire. Tchaikovsky had clearly been ahead of his time. It was only when he produced The Sleeping Beauty (1890) with Marius Petipa and The Nutcracker (1892) with Petipa and Lev Ivanov that the exceptional quality of his ballet music was fully valued. And following his death in 1893, interest in his ballet compositions continued to rise.

Dizzying fouettés

Tchaikovsky’s music – with its rich, evocative melodies, narrative character, ingenious use of leitmotifs and brilliant orchestration – was proved eminently suitable for ballet by Petipa and Ivanov, in particular.

In 1894, for a memorial concert in honour of the composer, Ivanov – assistant to Petipa at the Imperial Mariinsky Theatre, in St Petersburg – choreographed a new work to the music from the second ‘white’ act of Swan Lake. The success of the evening led to the decision to create a completely new version for the large ballet company – around 230 dancers employed by the tsar – which was premiered in St Petersburg, on 27 January 1895.

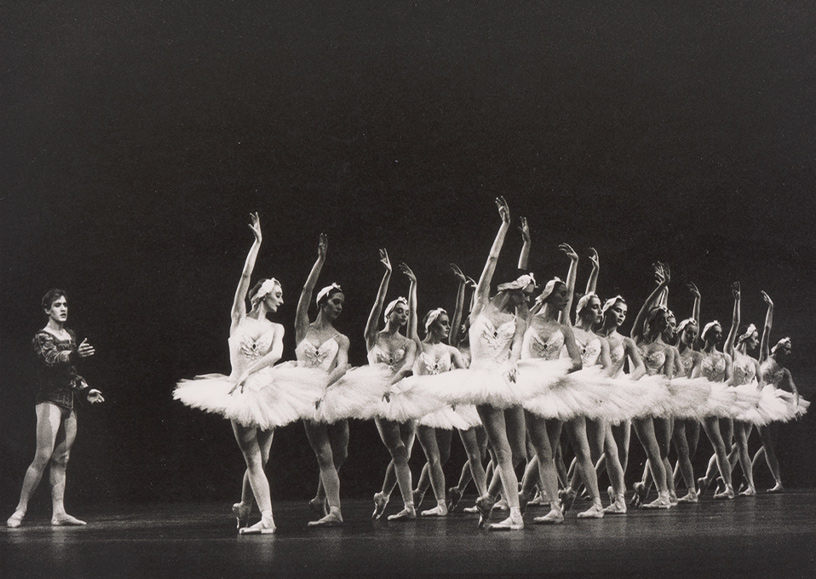

Petipa choreographed Acts 1 and 3, which take place in the palace gardens and inside the palace, respectively. What we know of this choreography is that it showed more or less a succession of separate ‘numbers’, dominated by colourful spectacle and technical virtuosity – including the ingenious pointework variations for which Petipa is renowned. All that has survived of Petipa’s contribution is the famous and notorious black swan pas de deux; the highlight of Act 3. In this duet, Odile deceives Siegfried with her sensuous, malicious powers of seduction. The 32 fouettés that form part of her variation (a dizzying sequence of turns on one leg that we owe to the original Odile, the Italian ballerina Pierina Legnani), are the terror and challenge of every ballerina – also because ballet fans worldwide count along.

Ivanov, responsible for Acts 2 and 4 of Swan Lake, was not concerned with outward display and virtuoso spectacle. In his ‘white’ acts, the emphasis is on inspiration, expressive power and musicality. Whereas Odile has to make a dazzling impression with her technique, the white swan Odette is supposed to be fragile and serene; a model of love and purity. In the dance world, the pas de deux that Odette dances in Act 2 with Siegfried is regarded as a marvel of lyricism and poetic movement. Apart from this duet, Ivanov’s choreography for the corps de ballet, the Big Swans and the four Little Swans (which can always count on a big round of applause) has survived largely intact. Ivanov’s Act 2 is still often performed unchanged today.

More than 150 versions

Over the past 130 years or so, more than 150 versions of have been created, most of which are based on the version by Petipa and Ivanov.

In the Netherlands, short excerpts from the ballet were danced by companies from abroad from 1937, and from 1949 the first Dutch dancers ventured to do the same. The first complete version seen in the Netherlands was performed by Sadler’s Wells Ballet, from London, in 1954. After this, both the Ballet der Lage Landen and the Ballet of the Netherlands Opera took Act 2 of Swan Lake into the repertoire.

Dutch National Ballet was the first company in the Netherlands to present complete versions of the ballet, in 1965 and 1973, created respectively by the Russian ballet masters Igor Belski and Marina Shamsheva and the Yugoslavian ballet master Zarko Prebil.

In its traditional form, Swan Lake is a true ‘ballerina ballet’, in which the double role of Odette/Odile forms one of the greatest challenges of the ‘cast-iron’ ballet repertoire. Many wonderful interpretations of the role have been given by leading international ballerinas like Galina Ulanova, Margot Fonteyn, Maya Plisetskaya, Carla Fracci, Natalia Makarova, Sylvie Guillem, Ulyana Lopatkina and Svetlana Zakharova.

In recent decades, however, various Swan Lakes have been produced in which the male soloist is given a more important – if not the most important – role, such as the productions by Rudolf Nureyev (some people jokingly called his interpretation The ballet named Siegfried), Mats Ek and Matthew Bourne, in whose all-male version the role of the swan queen is also danced by a man.

Vision of sincerity and purity

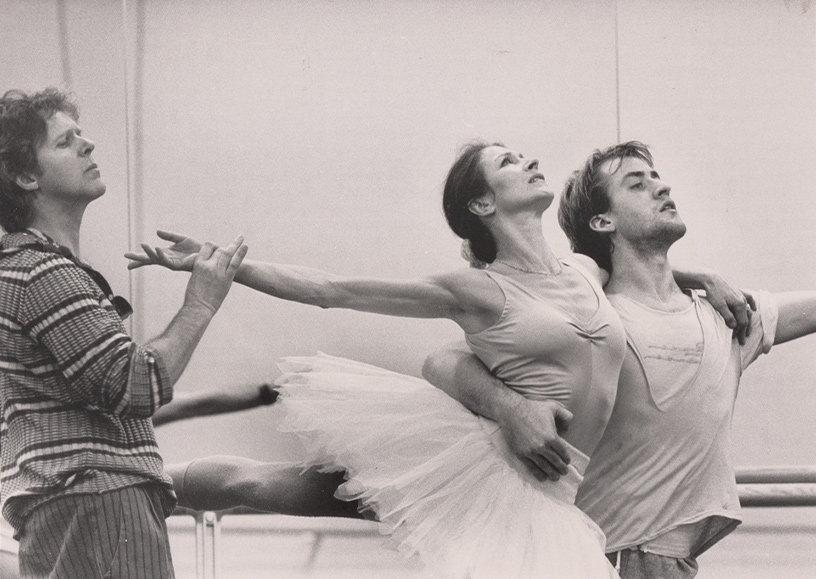

Rudi van Dantzig also placed far more emphasis on the role of the male soloist. His version – the first completely Dutch production, which he created with his good friend and artistic partner Toer van Schayk – premiered in Het Muziektheater (now Dutch National Opera & Ballet) in Amsterdam, on 31 March 1988, with star ballerina Alexandra Radius and principal dancer Alan Land in the leading roles.

In Van Dantzig’s eyes, Siegfried is a sensitive, idealistic young man, who turns his back on the conservative life of the court, which is riddled with corruption, nepotism and intrigue. The choreographer no longer sees Odette as a woman of flesh and blood who has been transformed into a swan, but as a vision symbolising sincerity and purity for Siegfried; the incarnation of his high-minded ideals.

Text: Astrid van Leeuwen

Translation: Susan Pond

The music of Swan Lake

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) composed just three ballet scores – Swan Lake, The Sleeping Beauty and The Nutcracker – but they brought about a revolution in nineteenth-century ballet music.

The music of Swan Lake

A minor revolution, however, as Tchaikovsky was not a composer to break completely with tradition. In any case, not with its good aspects. But he did refuse to produce mundane background music, like that of many of his predecessors and contemporaries – those hacks who behaved like obedient lapdogs. Tchaikovsky created autonomous and serious ballet music, comparable in many respects to his other orchestral works. Compared to the music of his predecessors and contemporaries, his ballet music is far more varied, filled with lyrical and symphonic elements, and above all narrative in character. After Tchaikovsky, Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes would continue along the path he had taken, regarding ballet as an integrated artwork, with equally important roles for music, dance and scenery.

Commissioned work

Tchaikovsky was probably not even deliberately trying to bring about the revolution that he did. He was asked to write Swan Lake in 1875 and accepted the commission, as he wrote to Rimsky-Korsakov, for the money, but also because he liked dancy music, a preference that is also reflected in many of his earlier compositions. He saw writing the music for a full-length ballet as a new challenge.

At the time, a ballet composer was expected to be at the service of the choreographer. For the premiere in 1877, this choreographer was the rather less successful Julius Reisinger. Whatever was considered unsuitable for dancing had to be rewritten, and if Reisinger thought that the score lacked a Russian dance, then Tchaikovsky had to compose one. That was simply the nature of the working relationship. After the premiere, opinions were divided, as far as the music was concerned. One critic thought it monotonous and completely unsuited to dance, whereas another found Tchaikovsky’s music so strong that he could hardly keep his attention on the feeble ballet. But whether or not they appreciated it, everyone agreed that Tchaikovsky’s music was different. The difference was that Tchaikovsky had not churned out everyday background music, but composed a mature work that was eminently suited to ballet, as proved later by the choreography of Petipa and Ivanov (and the multitude of choreographers who followed them).

Tonal approach

Tchaikovsky’s strength was that he related his composition to the subject matter. Not just to the tragic story, but also to the protagonists, their characters and their emotions. Rather than structuring his scores like a string of beads, in a succession of unrelated divertissements, as was customary at the time, Tchaikovsky composed his ballet music using broad symphonic lines, allowing themes and leitmotifs to develop. The musical meaning grew, deepened and blossomed, so that the storyline can be heard in the music.

Analysis of the music shows that each main character has their own key. B minor is the key of the swans and is the dominant key of the ballet. Siegfried has E major and Odette A minor and E major, among others, and everything blends wonderfully well tonally. The keys create specific associations with the protagonists, whilst also forming an essential part of the development of the whole work. This sort of tonal approach was new for ballet, and Tchaikovsky implemented it ingeniously. He knew how to express a story and how to convey an atmosphere in music that is difficult to capture in words. What could be more beautiful than representing the group of swans coming down to rest on a night-time forest lake with the unforgettable oboe solo, the harp and the vibrato strings? Or the sadness suggested by the wind instruments in the dance of the little swans? Or the herald of misfortune performed by the trumpets? That’s what makes Swan Lake the ballet it is: expressive, poignant, and moving.

Text: Maarten de Kroon

Revision: Stan Schreurs

Translation: Susan Pond

Painted shadows and new classical choreography

Follow the link below to read the interview with Toer van Schayk: set and costume designer of Swan Lake and choreographer of the folk dances in the third act.

Painted shadows and new classical choreography

Choreographer, visual artist, designer and former principal with Dutch National Ballet: the title ‘multidisciplinary artist’ could hardly be more applicable to Toer van Schayk. For Rudi van Dantzig’s production of Swan Lake, he designed the sets and costumes, as well as choreographing the folk dances in the third act. Exactly 35 years after its world premiere, Van Schayk is still involved in the preparations for the ballet.

“I’ve just been re-reading Tchaikovsky’s letters and diaries”, says Van Schayk. “When he writes about working on a particular piece, you think ‘Gosh, we know it as part of a classic masterpiece, but for him it was simply a task he’d completed that day.”

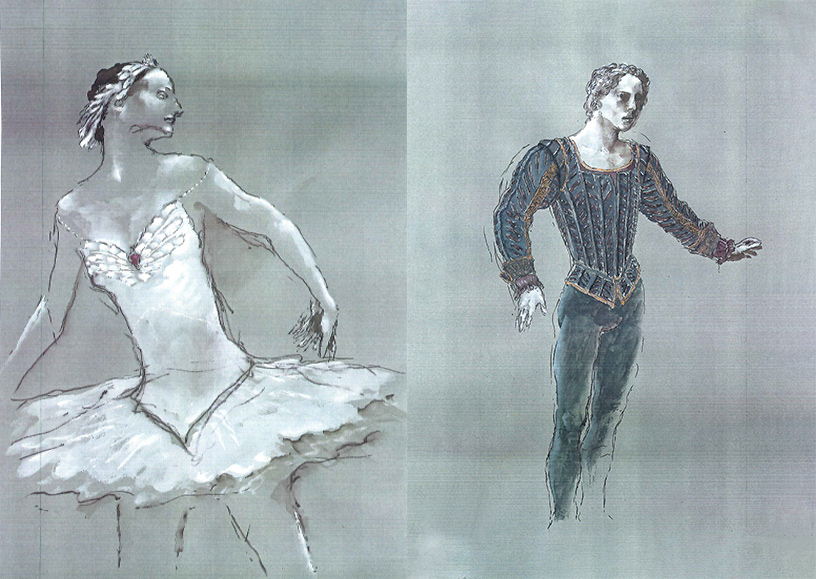

Flat sets and heavy skirts

Just as for Rudi van Dantzig, Tchaikovsky’s music was one of the main sources of inspiration for Van Schayk as well. For the set and costume designs, he also took inspiration from Dutch paintings of the seventeenth century. “Swan Lake is often put in a Gothic setting, but I’m not such a fan of the pointed Gothic. I prefer the rounded forms of the Baroque, so I based the sets and costumes on paintings from that period. In doing so, I deliberately didn’t design the scenery in three dimensions. Everything’s flat, and the shadows are painted onto the scenery, as if it were a painting.”

In the Baroque style, Van Schayk could also indulge himself in the costumes, especially with regard to the artists who don’t have to dance. “The extras can wear big, heavy skirts, which was a nice change from the lightweight costumes you always have to make for the dancers.” But of course Swan Lake has a great number of that sort of costume as well. “I really enjoyed designing them too. For example, the dresses for the women at the garden party in the first act have skirts made of layers of organza (a thin, transparent fabric – ed.) in different colours, so that you see one colour through the others.”

Like new

Besides designing the sets and costumes, Van Schayk also choreographed the folk dances in the third act, at the request of Rudi van Dantzig. “At the time, Rudi said, ‘Those folk dances aren’t really my thing.’ And he didn’t have time for them either – it’s a mammoth task creating such a big production – so he asked me to do them. Of course, Rudi and I had been working together for years already, so it all went very smoothly.” Unlike Van Dantzig, Van Schayk has always had a great affinity with folk dancing. “As a choreographer, but also when I was still a dancer. For example, I always used to really enjoy doing the Russian dances in Petrushka (a ballet choreographed by Michel Fokine to music by Igor Stravinsky – ed.).”

Practically the only choreography that has survived from the third act of the original Swan Lake is the famous black swan pas de deux, for Odile and Prince Siegfried. So it was up to Van Schayk to create completely new choreography for the folk dances in this act. But how do you do that within the boundaries and traditions of an iconic classical ballet? “The best way is to pretend that the ballet is totally new and is being performed for the first time. Then you don’t have to think, wonder how it would have gone back then, and you have the greatest freedom. That’s also the way I worked with Wayne Eagling on creating our new production of The Nutcracker, although in that ballet there are fewer sections that are set in stone.”

Not by the book

In Swan Lake, the set sections come mainly in the second and fourth acts, which are also known as the ‘white acts’. “In the second act, Rudi remained completely true to the original choreography, and although he created a new fourth act, he did so in the spirit of the nineteenth-century ballet. Some choreographers have made totally new versions of Swan Lake, but Rudi always had too much respect and admiration for the ballets of Marius Petipa and didn’t want to take a heavy-handed approach to it.” However, this doesn’t mean that Van Dantzig simply adopted the surviving sections of Swan Lake. “He incorporated many of his own ideas into the production, such as his vision of the role of the prince, so he certainly didn’t just go by the book. He also added a great deal of completely new choreography, like the courtiers’ waltz in the first act. Rudi did a really good job on that.”

Heated studio rehearsals

Just as Van Dantzig was in awe of Petipa’s production in the process of creating his Swan Lake, so the ballet masters of Dutch National Ballet have great respect for Van Dantzig’s production, in turn, says Van Schayk. That is, in part, why the ballet has hardly changed since its premiere in 1988. “The ballet masters are very loyal, and making changes is generally frowned on when reviving a ballet. That’s born of necessity, as of course for a long time it wasn’t possible to write down ballets. So if things weren’t remembered properly, then they were lost.” This tradition sometimes leads to heated discussions in rehearsals. “The older dancers, in particular, can get very worked up and shout, ‘that’s not right!’ or ‘you have to do it like this!’ You can get into big arguments about it.”

The choreographer himself, now aged 86, will be attending some of the studio rehearsals for the coming series of performances. “Not to teach the dances, though. That’s the job of the ballet masters, because I can’t show all the steps so well anymore. But if there’s something I don’t like or I think something needs improving, then I’ll certainly say so.”

Exactly 35 years after the world premiere, Van Dantzig’s production of Swan Lake is still working its magic, and the ballet – internationally regarded as one of the most beautiful Swan Lakes ever – appears only to be gaining in popularity. “And choreographically speaking, the production really is a beautiful one”, says Van Schayk. “Rudi did that very well. And”, he adds, laughing, “maybe a bit of the magic is in the scenery too. Because actually, that’s not so bad either.”

Text: Rosalie Overing

Translation: Susan Pond

‘You always want to be even better than you are’

Eight pupils of the Dutch National Ballet Academy on their role in Swan Lake.

‘You always want to be even better than you are’

Rudi van Dantzig thought it was essential that children danced in the peasants’ party in the first act of Swan Lake. So since the premiere in 1988, many young dancers have taken on the role of peasant child – a very demanding role for their age. For these programme notes, we talked to eight pupils of the Dutch National Ballet Academy who are among the latest generation to take part. “Which Dutch National Ballet dancer will be lifting me up on stage? I really don’t mind. So long as he doesn’t drop me.”

The corona pandemic, they say, barely affected their opportunities to perform with Dutch National Ballet. Julia Lemaitre (13), Juliet te Lintelo (12), Keira Wiss (13), Ichiro Yanagi (14), Dirk Hoogenbosch (14), Chris Ligthart (14), Luc Smith (13) and Jacob Wysny (13) all danced in The Nutcracker and the Mouse King. The four girls also took part in Raymonda, and Julia and Juliet performed in Giselle as well, when they were still pre-NBA pupils.

Juliet says, “It’s such fun to be on stage and to get the chance to perform for an audience.” Keira says, “What I really like is that you can get into another character and really become immersed in your role.” Ichiro adds, “And you get to wear the most wonderful costumes, with make-up to match. In Raymonda, I was a flower girl and I had the most beautiful pink dress.”

But things do go wrong sometimes, they say, giggling. Juliet tells, “In Giselle, the cart I had to be lifted onto, as a peasant child, nearly overturned once.” Julia says, “I was a young lady in the same ballet. I’d been told to stay close behind the dancers in front of me when I came on stage, but I accidentally stepped on the train of one of their dresses, and a dancer hissed, ‘You have to keep more distance’.”

Second home

All the boys have also taken part in at least one other production besides The Nutcracker and the Mouse King: in Frida, Prometheus or the Coppelia film, or in II barbiere di Siviglia with Dutch National Opera. Jacob says, “We may have missed the odd opportunity because of corona, but we’ve still had plenty to do.” Dirk says, “I really enjoy the rehearsals with the dancers of Dutch National Ballet. It’s so great to watch all those adult dancers at work.” Chris adds, “It’s also very special to see how a performance is put together from up close. First the rehearsals in the studio, and then how everything eventually comes together on stage.” Jacob says, “When I’m in Dutch National Opera & Ballet, I really feel that this is what I want. I feel so at home there.”

The corona pandemic even brought Luc an extra opportunity. “The first time I was going to take part in The Nutcracker and the Mouse King I was cast as one of the children at the party. But the production had to be postponed for a year because of the lockdown, and the second time around I got to dance the role of Frits, Clara’s younger brother. That time as well, the new corona measures meant we couldn’t perform a whole series, but I still got to dance two live performances and one livestream.”

Audition

The four boys – for whom, unlike the girls, there were no roles in Raymonda – think it’s wonderful that soon they can ‘appear again at last’ in a whole series of performances for a packed theatre. Luc says, “Soon after the summer holiday, we heard we could take part in Swan Lake.” Jacob says, “But we didn’t know then that all the boys in our class, NBA 4, would be taking part, spread over three casts.” Keira, who is in NBA 3 like the other three girls, says, “First, we were told that the girls from NBA 4 would be taking part, so for us it was a fantastic surprise that we could suddenly do the audition.”

Shortly before the autumn holiday, Judy Maelor Thomas, ballet mistress with Dutch National Ballet, came to Agamemnonstraat in Amsterdam-Zuid, where the pupils of NBA 1 to 4 do their classes, to hold the audition. Julia thought it was “pretty scary”. Juliet remarks, “She also gave plenty of corrections during the audition.” Ichiro adds, “And the worst thing is you can’t always show what you want to show. You always want to be even better than you are.” Chris says matter-of-factly, “Auditions are stressful anyhow.” Jacob says, “If I’m insecure, you see it in my body language. So if I know something’s important, I consciously press the switch and just go for it. Then everything just goes automatically, and I even manage to put feeling into the steps.” Keira comments, “It was a bit irritating that the audition was on Thursday and we didn’t hear the results till Monday. So we spent the whole weekend really wound up.”

Both dancing and acting

Ichiro, who moved to the Netherlands from Japan three years ago, saw Swan Lake once in her homeland, and Julia saw the ballet when she visited her grandma in Russia. Only Juliet and Dirk – who also saw a version once in Italy – have seen a live performance of the Dutch National Ballet’s production, choreographed by Rudi van Dantzig, when they were very young. Dirk says, “What I remember most of all is that the scenery was so beautiful.” And Juliet adds, “Actually, all I remember was that the performance was very long.”

The fact that their role in Van Dantzig’s production is so big – they’re on stage nearly all the time in Act 1 – is something they find ‘really cool and very frightening’ at the same time. Julia says, “In previous productions, it involved mainly running around and acting.” Juliet adds, “But now we’ve got a really big dancing role.” Keira says, “And we have to do steps we haven’t learned yet in our NBA 3 classes.” Luc adds, “So it took quite a long time to learn the choreography. It was only two weeks ago that we learned the last steps.” Julia says, “You have to remember the order of all those steps, and act at the same time.”

The latter is a big challenge, they say. Chris remarks, “Often, you have to react to an adult dancer, but of course during the rehearsals at school, that dancer isn’t there.” Dirk agrees, “So that’s difficult, having nobody to look at while you’re acting.” Luc says, “But luckily Dario (Dario Elia, the teacher rehearsing the ballet with them – ed.) sometimes plays the role of the adult dancer for a moment.”

Dario also talks to them regularly about how Rudi van Dantzig and designer Toer van Schayk visualised certain scenes, such as those in which two of the boys get into an fight at the back of the stage. Chris says, “They’re having a discussion that ends in anger.” Luc adds, “According to Dario, Rudi wanted us to get really angry with each other.” And Jacob explains, “Dario also taught us to look around us really well. And to be flexible. If something doesn’t go according to plan, we have to be able to respond to it.” Luc adds, “He also knows exactly which moments we have to be careful not to get in the way.”

Shoulder lift

What makes it all extra exciting is that Swan Lake is the first production in which the children really dance in couples. Ichiro says, “I found that really difficult at the beginning. I’d never danced with a boy before.” Dirk says, “We (the boys – ed.) are in NBA 4 and the girls are in NBA 3, so we hadn’t had much contact before this.” Julia says, “At the first rehearsals, we were all a bit shy.” And Chris adds, “But now it doesn’t feel so awkward anymore.”

Something a few of them are still concerned about is that in the production all eight of them get lifted by a male dancer from Dutch National Ballet onto his shoulder. Julia says, “It all has to happen very quickly as well.” Juliet adds, “But it mustn’t look rushed or strange.” Chris remarks, “In the rehearsals, we’ve all been lifted once by Dario already. You don’t realise it, but suddenly he’s behind you.” Keira says, “So that you don’t fall, you have to lean forwards a bit, but it still has to look as if you’re sitting upright.” Luc says, “And when you come down, then you shouldn’t lean forward anymore.” Jacob adds, “Because then you fall forward and lose control.” Chris says, “And then during the lift, you also have to watch out that you don’t kick the dancer by bringing your legs too far back.”

When asked which male dancer they’d most like to lift them up, the girls look blank. Juliet says, “Our idols are the ballerinas, of course.” Julia says, “What they can do is what we’ll have to be able to do later.” Juliet says, “My big role model is Olga Smirnova.” Julia and Ichiro cry in chorus, “Riho Sakamoto!”, and Keira can’t choose between Maia Makhateli and Floor Eimers.

Jacob’s heroes are Constantine Allen and Jakob Feyferlik, while the other three boys don’t really have a preference. Chris says, “I focus more on the performance as a whole.” Luc says, “In the corps de ballet, I think some are better than others, but the soloists are all fantastic.”

So who would they like to lift them then? Chris would like, “Someone who’s good at it.” Luc adds, “In Nutcracker, there was a dancer who was no good at lifting at all, so I really hope I get someone strong.” Juliet says, “I really don’t mind who, so long as I don’t fall.” And Jacob explains, “Because in that case, it’s mainly you who looks a fool.”

Text: Astrid van Leeuwen

Translation: Susan Pond

A swan’s skirt made of ten square metres of tulle

Read more about the tutus from Swan Lake by following the link below.

A swan’s skirt made of ten square metres of tulle

An essential element in classical ballet and in Swan Lake: the tutu turns a corps de ballet into a harmonious group of elegant swans. But just how ‘classical’ is the tutu itself? And how are these iconic protruding skirts made? Oliver Haller, head of Dutch National Ballet’s costume department, talks about the nineteenth century and huge mountains of tulle.

“If the tutu didn’t exist, I might not be working here! Apart from the fact that it’s attached to a beautiful bodice, I’m also really fascinated by the tulle garment itself”, begins Haller passionately. “The tutu isn’t just any old ‘skirt’ – it’s taken the tutu at least a hundred years to reach its ultimate form, and there’s a great deal involved in the process of making them.” Although the tutu is seen as an absolute classic, it’s actually a much more recent invention than you might expect. “The tutu has only existed in its current form since around World War II. But before that, it already started its evolution at the beginning of the nineteenth century.”

New lace, new opportunities

This evolution came about through an unintentional discovery. “In those days, people were crazy about lace. So a Mr Heathcoat from England wanted to develop a cheaper variety, but a flaw in his loom meant that he accidentally produced a new fabric. As he thought it was actually a very interesting material, he decided to manufacture more of it. And it became a real rage, which then crossed over to France as well. There, in the little town of Tulle, lots of lace makers decided to start using their machines for the production of this new fabric, which is how the material got its name.”

The invention of tulle opened up new possibilities for ballet costumes. Skirts made of the fabric were worn for the first time in 1831, in the production Robert le diable. “It was actually an opera, but the third act is viewed by some as the first ballet blanc: a scene where the principal ballerina and the corps de ballet of women are completely draped in white. This look became popular and the white tulle skirts were copied in many other ballets. However, these skirts were still very long, reaching right down to the ankles, as in those days no glimpse was allowed of the ballerinas’ legs, let alone their knees.” It was only when the role of the ballerina become more important and the dance steps demanded more leg room that the tutus were shortened – until eventually they reached the average length we see today.

Specialism

The short tutus, as we still know them today, are technically very different from the original romantic tutu. “The basis is actually a pair of pants, onto which we sew more than ten square metres of tulle in total. They’re all straight strips, in gradually decreasing sizes. On our Swan Lake tutus, for example, the top strip is 40 centimetres wide and 6.5 metres long, the next is 38 centimetres wide and 5.5 metres long and the bottom layer is just 4 centimetres wide and 3.5 metres long. These strips are attached in turn around the girth of the hips, so that the straight pieces automatically form a circle.”

That may sound simple, but… “All that tulle has to be pulled under the foot of the sewing machine and sewn with very small stitches to gather it. So it’s a really big job, as well as a precise one. There are very few people in the world who can do it and who are really passionate about it – and I must say I’m very happy they exist! We had many of our tutus made by two English gentlemen who lived on a farm in Essex. Every morning, they got up early and didn’t go to bed again until each of them had finished another tutu. Specialists like them can make one tutu a day, but the process normally takes around 38 hours.”

Refined costumes

Although Dutch National Ballet’s production of Swan Lake premiered in 1988, many of the original – over three hundred – costumes are still used today. “Two series ago, we did have new tutus made, to which we attached the bodices from the old costumes. I had to give them a good soak beforehand – the dirt that came off them! – but they’re still really beautiful. Just like the rest of the costumes, they were made with the utmost care. All the decoration is very subtle and refined, and this style really reflects the character of Toer (van Schayk, the designer – ed.) as I know him. Some companies choose to work very obviously with feathers, but in our costumes they’re suggested in a more abstract way. For example, you can make out feather patterns, made of fabric and gold stitching, and there are a few more true-to-life feathers in the headdresses.”

Recent icon

And just as fine feathers make fine birds, so these detailed costumes are one of the things that make Swan Lake. “The image of the corps de ballet in white tutus is now fairly iconic for Swan Lake. Maybe also partly because all those layers of tulle resemble the downy layers of feathers on a swan. It appeals to the imagination and it remains a wonderful sight. Long legs, springy tutus and finely detailed bodices – ballet doesn’t get any more beautiful than that, does it?”

Text: Lune Visser

Translation: Susan Pond

Programmaboek

BECOME A FRIEND OF DUTCH NATIONAL BALLET

As a Friend you support the dancers and makers of Dutch National Ballet. You are indispensable to them and we are happy to do something in return. For Ballet Friends we organize exclusive activities behind the scenes. You will receive the Friends magazine from us, will receive priority when selling tickets and a 10% discount in the National Opera & Ballet shop.