‘All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others’

On George Orwell and the continued appeal of Animal Farm

Text: Laura Roling

Animal Farm by George Orwell was published in 1945, just after the Second World War had ended. This satirical parable about Stalinism became one of the most widely read and relevant books of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries

George Orwell gave Animal Farm the somewhat misleading subtitle of ‘A Fairy Story’. It would have perhaps been more accurate to call it ‘An Animal Fable’ because Orwell’s tale owes a debt in many respects to this centuries-old genre in which tales about animals are used to expose and criticise human behaviour.

Portrait: George Orwell (1943)

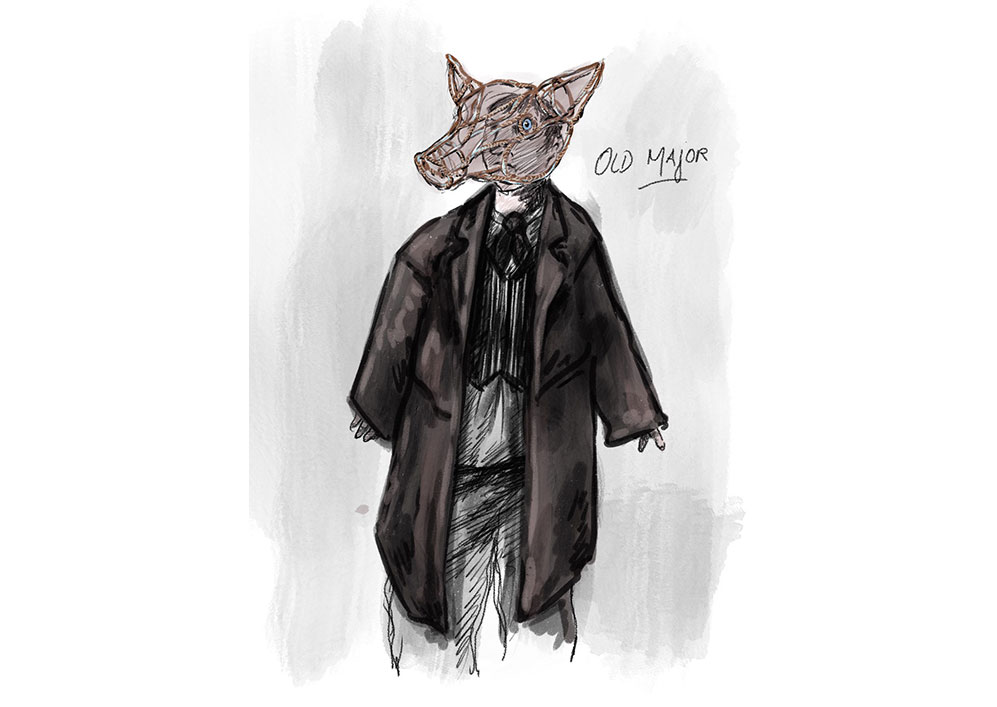

The parallels between the animals in Animal Farm and historical figures and events are indeed unmistakable. The book opens in a farm barn where the animals have gathered around the venerable pig Old Major — a reference to Vladimir Lenin and his Marxist ideas — who calls on them to revolt against the humans. He teaches the animals the song ‘Beasts of England’ (reminiscent of the Internationale) and tries to impress upon them the image and ideals of a post-revolutionary world.

However, Old Major does not live to see the revolution; it breaks out suddenly and is soon over, with the animals successfully driving the humans out. In its wake, the animals try to build a new, post-revolutionary society. The pigs Snowball (Leon Trotsky) and Napoleon (Stalin) draw up seven golden rules based on Old Major’s speech:

THE SEVEN COMMANDMENTS

1. Whatever goes upon two legs is an enemy.

2. Whatever goes upon four legs, or has wings, is a friend.

3. No animal shall wear clothes.

4. No animal shall sleep in a bed.

5. No animal shall drink alcohol.

6. No animal shall kill any other animal.

7. All animals are equal.

Barely have the pigs finished writing the commandments on the wall when they start claiming more and more privileges for themselves. As the animals responsible for all the ideas, they excuse themselves from the hard physical labour on the farm and decide they should eat most of the milk and apples. When Snowball presents a plan for the construction of a windmill that he says will eventually make life on the farm more pleasant and comfortable, Napoleon freezes him out and he is forced to flee. With a private army of dogs (a reference to the NKVD, the forerunner of the KGB) and the pig Squealer as his mouthpiece spouting propaganda, Napoleon increasingly develops dictatorial traits, presiding over a regime — like that of Stalin — based on lies, indoctrination, threats and executions.

Little remains of the ideals of the Seven Commandments by the end of Animal Farm: Napoleon is in cahoots with the neighbouring farmers; he wears clothes, sleeps in a bed, drinks copious amounts of alcohol and has other animals executed (a reference to Stalin’s Great Purge from 1936 to 1938). And the Seven Commandments on the barn wall have surreptitiously been reduced to a single commandment: ‘All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others’.

Criticism of the Soviet Union

George Orwell (the pen name of Eric Arthur Blair) wrote Animal Farm towards the end of the Second World War. He initially had some trouble getting it published. Stalin’s Soviet Union had been an important ally of the UK in the war and the British wanted to avoid causing offence. Gollancz and Faber & Faber were among the publishers that rejected the manuscript. The London publishing company Jonathan Cape was on the point of printing the book but was persuaded not to after all by a civil servant from the Ministry of Information — possibly a Russian spy in reality.

Despite this initial reluctance, when Animal Farm was finally published in Britain in 1945, by Secker & Warburg, it was a resounding success. The novel did well in the United States too. The collapse of the wartime alliances and the first signs of the Cold War undoubtedly played a role in this. The Western world had become more receptive to Orwell’s anti-Soviet message as it eyed the communism of Russia — or indeed, in the case of the US, any form of socialism at all — with great distrust.

However, George Orwell himself was no opponent of socialism, or even communism as such. In the Spanish Civil War, he had fought alongside Spanish Trotskyists. As a firm believer in democratic socialism, it was Stalin’s betrayal of the ideals of the revolution and his totalitarianism that Orwell felt so strongly about and that he criticised in his fiction and socially engaged journalism

In 1947, he wrote a preface to the Ukrainian edition of Animal Farm, published that year (which was mainly aimed at Ukrainians in exile living in the parts of Western Europe controlled by the British and Americans). “In my opinion, nothing has contributed so much to the corruption of the original idea of Socialism as the belief that Russia is a Socialist country and that every act of its rulers must be excused, if not imitated. And so for the past ten years I have been convinced that the destruction of the Soviet myth was essential if we wanted a revival of the Socialist movement.”

First Commandment: Whatever goes upon two legs is an enemy

RELEVANCE IN THE POST-SOVIET ERA

We are now living in a very different world. Statues of Stalin were removed from public spaces in the Soviet Union in the 1960s and the city of Stalingrad was renamed Volgograd in a process of de-Stalinisation. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Soviet Union was dissolved in 1991. The American political scientist Francis Fukuyama even proclaimed the ‘end of history’. “What we may be witnessing is not just the end of the Cold War, or the passing of a particular period of post-war history, but the end of history as such: that is, the end point of mankind's ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.”

Fukuyama’s words seem naive from the perspective of 2023. While Stalin’s totalitarian reign of terror may have ended, the mechanisms exposed in Animal Farm are as relevant today as they were in 1945. The way the rhetorically gifted pig Squealer is able to convince the farm animals of his ‘alternative facts’ is highly topical. Many people turned up to Donald Trump’s inauguration as president of the United States, but the crowds were not as big as for Trump’s predecessor Obama. When the media remarked on this, Trump was incensed and spoke of “fake news”. According to his spokesperson Kellyanne Conway — who was sent out to perform as a kind of Squealer — his claim had been based on “alternative facts”. The machinations of politicians and their spin doctors often seem to have been taken straight from Animal Farm. In Western Europe too, democratic processes are increasingly under pressure and people stay within their social-media bubbles where they hear only a certain version of events.

There are parallels too between Putin’s Russia today and Animal Farm. The Kremlin is framing the ‘special military operation’ in Ukraine as a sequel to the Second World War, but this time with the Russians fighting Western fascism in Ukraine. Many Russians are influenced by such rhetoric. On 2 February 2023, the eightieth anniversary of the victory over the Germans in Stalingrad was celebrated in Volgograd. To mark the occasion, the city was temporarily renamed Stalingrad, and a statue of Joseph Stalin, no less, was ceremoniously unveiled while President Putin looked on. It is not the first Stalin monument to appear in the city in recent times: in 2019, a concrete bust of Stalin was unveiled to commemorate the 140th anniversary of his birth. The Reign of Terror seems to have been forgotten and replaced by an alternative truth.

- Animal Farm will run from 3 to 16 March at Dutch National Opera.