La traviata: Verdi’s contemporary operatic creation

Whenever Giuseppe Verdi’s La traviata graces the stage, an indelible image springs to mind in our collective memory: the famous ‘brindisi,’ sung by a well-heeled tenor and a soprano in an equally extravagant hoop skirt. While La traviata may have carved its place in history as a period costume drama, Verdi’s immensely popular opera is, in reality, more contemporary than we typically imagine. And the composer himself understood this better than anyone else.

Text: Eline Hadermann

Amidst his composition work for Il Trovatore in 1853, Giuseppe Verdi accepted a commission from Venice’s Teatro La Fenice for the following year. However, the choice of subject matter eluded him for a while, until September 1852, when Verdi requested a copy of Alexander Dumas fils’ La Dame aux Camélias.

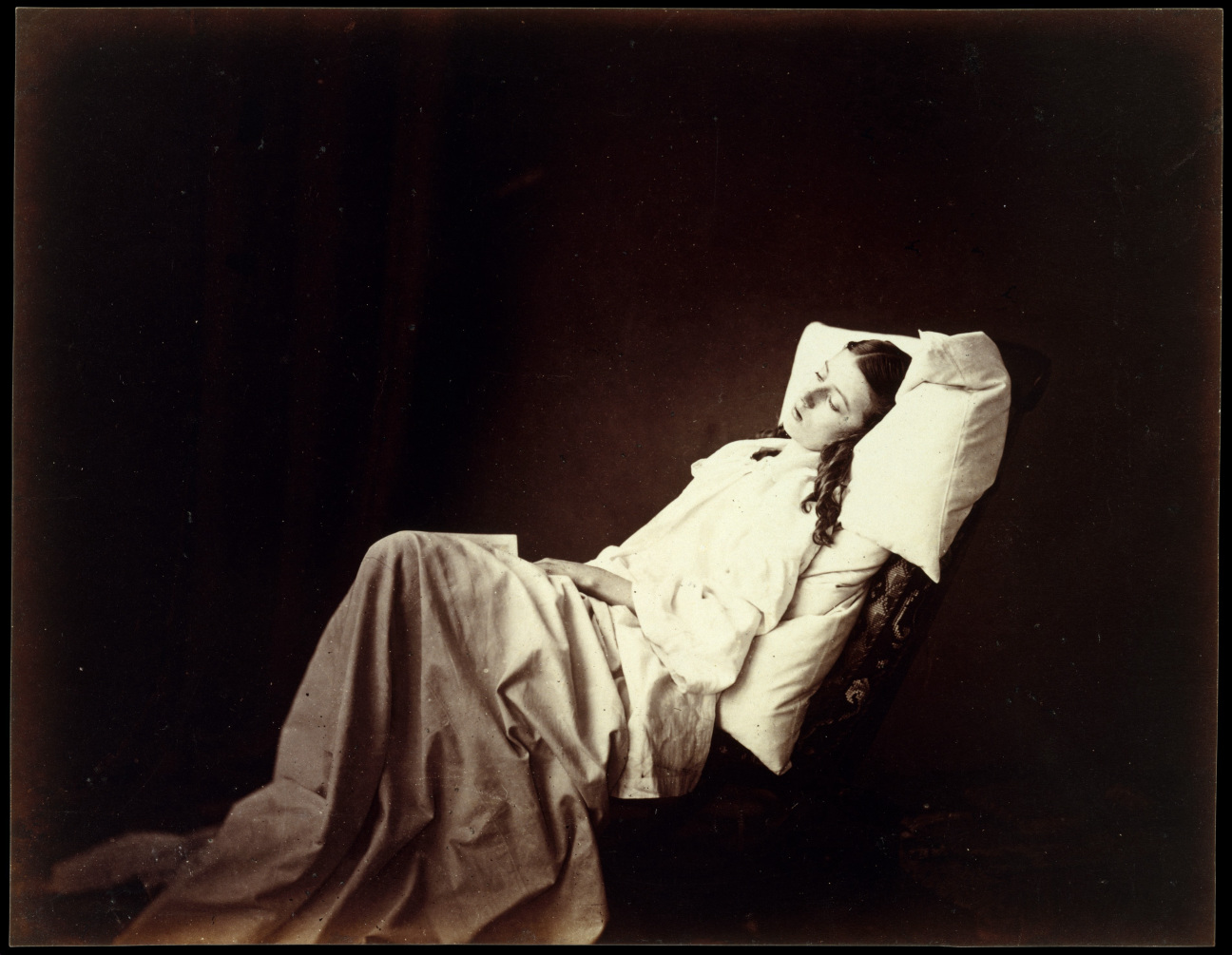

Dumas’ play, which premiered in Paris earlier that year in February, had already made a profound impact on Verdi. This drama, adapted from the book to the stage, departed from the prevailing French theatrical trend. It moved away from the romanticism of Victor Hugo and the bourgeois, moralistic texts of Eugène Scribe, instead presenting a contemporary story set in the Paris of its time. The tragic narrative of a courtesan succumbing to tuberculosis was rooted in Dumas’ own life – he based the central character on his own beloved, the renowned Parisian courtesan Marie Duplessis. Beyond the tragic love story, it also put a controversial disease at the forefront.

According to librettist Francesco Maria Piave, the writing duo was instantly captivated by Dumas’ theatrical text, and soon the choice of subject matter seemed settled. Verdi appeared content with his decision to embark on a modern narrative after a series of operas with historical themes. In January 1853, he penned a letter to his close friend Cesare De Sanctis, stating, “It is a subject of our time. Others might not have chosen it due to conventions, the era and a thousand other ridiculous objections.

Censorship

These ‘objections’ would come from the censorship authorities. In mid-nineteenth-century Italy, the censors were particularly restrictive, often intervening during the writing of librettos and dress rehearsals to ensure that contemporary morals were not offended. French theatre, originating from a revolutionary war-torn country, was considered immoral, and words referring to the Church were strictly prohibited.

However, it wasn't just censorship that presented a challenge for La traviata. In addition to the numerous concessions Piave and Verdi made in the libretto, which stemmed from a French theatre text and occasionally had the courtesan Violetta Valéry addressing church fathers, the composer also had to compromise on his staging preferences. Verdi wanted it to appear as modern as possible, with contemporary costumes, so that the audience could identify with a contemporary setting. But the censors were unrelenting: the opera had to be presented in an early eighteenth-century mise en-scène, with characters dressed in equally historical costumes. The premiere of La traviata was not presented as Verdi had envisioned it, and he even considered it a flop, partly because he believed the cast singers were not up to the vocally demanding roles.

'Consumption' and public debate

However, with La traviata, Verdi aimed to do the opposite of what the censors imposed on him: to create an opera performance where the spatial and temporal distance between the audience and the stage was as small as possible. This was a bold move in the Italian opera culture of the time. Defying the conventions of the genre, he traded romantic, heroic love stories from a distant past for contemporary social issues: those of prostitution and an epidemic disease that gripped nineteenth-century Europe.

Scientific research into what was known as 'consumption' in the nineteenth century was still in its early stages in the 1850s – the bacterium itself was only discovered in 1882 – which led to speculation about its cause and cure. The disease was highly susceptible to speculations about its contagiousness. Tuberculosis susceptibility was often attributed to undesirable environments and immoral habits, such as indulging in alcohol, sex and drugs. This referred primarily to the artistic bohemians, as well as the wealthy aristocracy and their demi-monde – the mistresses who lived in opulence thanks to the wealth of their lovers. Attitudes towards the industrialisation and rapid urbanisation of nineteenth-century Europe, which had partly facilitated such hedonistic circles, suddenly became more ambivalent.

IN THREE-QUARTER TIME

Verdi musically conveys his critical perspective on his increasingly modern world in La traviata. While his composition formally adheres to the conventions of the time and contains few radical innovations, Verdi’s musical language extends from the daring subject he had chosen. Musicologist Carolyn Abbate points out that the frequent waltz rhythms and melodies are perfect evocations of the French ‘couleur locale.’ Moreover, the three-quarter time signature also embodies the speed, constant movement and transience of the rapidly changing world in which the characters find themselves.

Remarkably, Verdi’s use of the waltz serves not only to create the right atmosphere but also to delineate the characters. From the opening scene and the famous drinking duet to her grand aria ‘Addio, del passato’ in the third act, Violetta Valéry is almost consistently accompanied by waltz rhythms. In this way, she is musically portrayed as the first opera character in history who, through an explicitly mentioned illness, symbolizes the pitfalls of the nineteenth-century consumer society almost until her last breath.