‘Mata Hari was a style icon’

Text: Astrid van Leeuwen

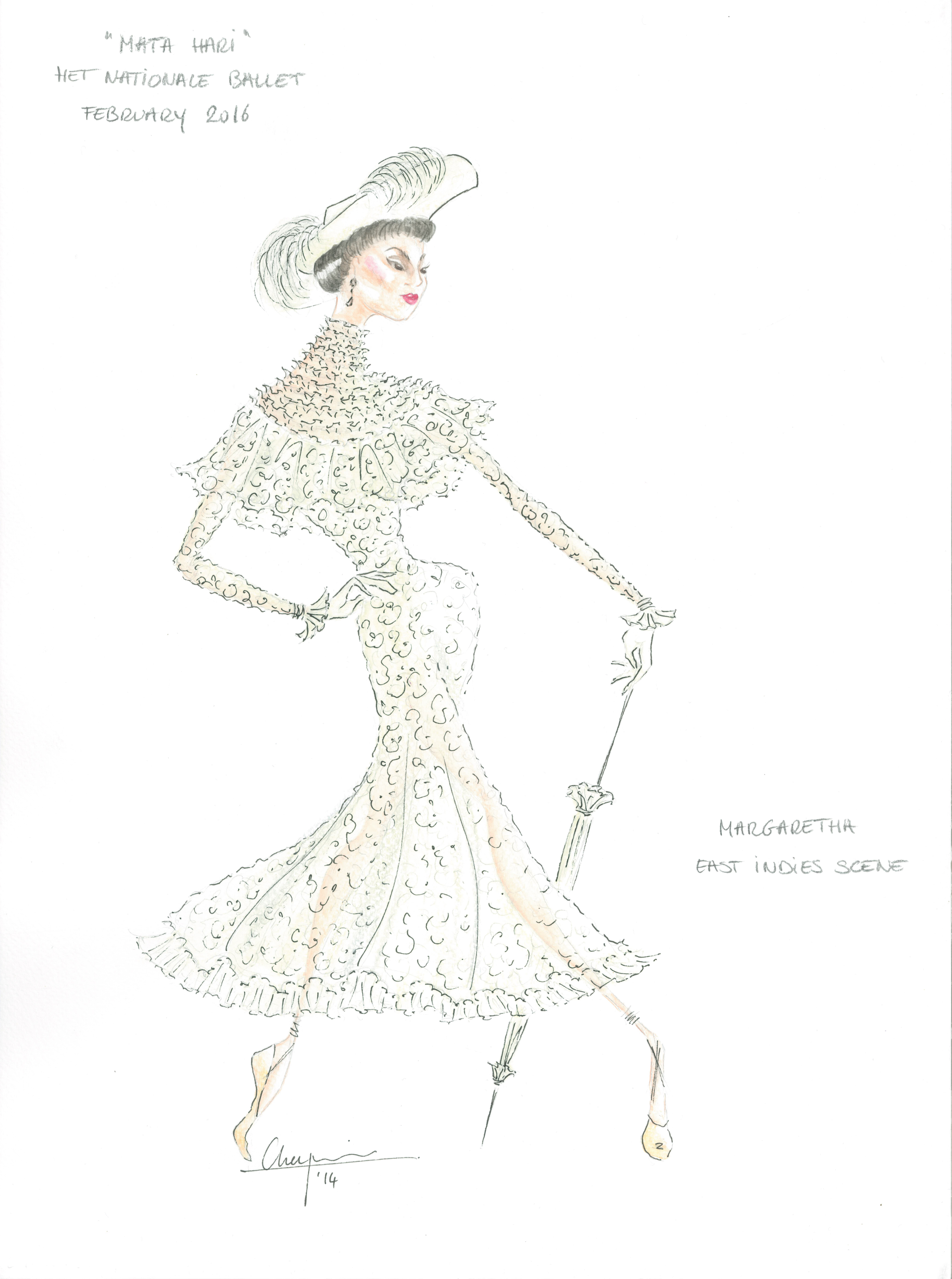

Interview with costume designer François-Noël Cherpin

Fashion and costume designer François-Noël Cherpin saw Mata Hari as a very special challenge. It was the first time that a ballet production in which the Frenchman was involved was linked so directly to the fashion of his homeland. “Fantastique!”, he says, with big dark twinkling eyes, thinking of the wealth and variety of his sources of inspiration. “But I didn’t stay historically accurate. I wanted a lighter, more contemporary look, without frou-frou and frills”.

François-Noël Cherpin used to know Mata Hari as he thinks most people know her. “As that exotic dancer and spy, who’s had several films made about her, like the one with Greta Garbo in the main role. But quite honestly, I’d never realised she was Dutch”.

Things have changed since then. Nowadays you can safely say that Ted Brandsen’s regular costume designer is an expert. He laughs, “Once Ted started talking about her ten or eleven years ago, she was everywhere”.

Not only did Brandsen infect him with his fascination, but there was of course an extra dimension for the fashion-loving Cherpin. “Margaretha Zelle, alias Mata Hari, was an extremely fashionable woman. Even in the most difficult periods of her life – like when her father went bankrupt or when her marriage was on the rocks – she was still immaculately dressed and groomed. During that marriage, which took her to Indonesia, she was a high society lady who carefully followed the European fashions. Later on, too, when she was a successful dancer, she was one of the best-dressed women of the Parisian beau monde”.

RAPID SUCCESSION OF FASHIONS

The ballet Mata Hari covers a period of almost forty years; a time when the world underwent radical change, which was of course reflected in the fashions. “We start off around 1880, the era of the second bustle or tournure, when the seat of a lady’s dress was ‘raised up’, as it were, with cushions”. This was followed by the Belle Époque, one of Cherpin’s favourite periods. “It was an exceptional time, with beautiful, refined fashions, whereby a woman’s silhouette became S-shaped, with extra emphasis on the breasts and buttocks”. At the start of the twentieth century, orientalism was ‘en vogue’. “Partly as a result of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, art from the Orient became very popular all of a sudden, and that was reflected in the fashions”. But shortly afterwards, the fashion scene changed again. “Led by fashion designer Paul Poiret, the silhouette became longer and thinner, and the corset disappeared. It was a forerunner of the ‘boyish look introduced by Chanel after World War I”.

For the extravagant Margaretha Zelle, all these changes were a source of inspiration, says Cherpin. “She was a style icon; a star à la Lady Gaga or Madonna. She made an appearance at all the big events, and everyone wanted something from her – to be near to her and to share in her success”.

A CONTEMPORARY TWIST

Beaming, Cherpin says that he could really go to town. “Totalling three hundred designs, Mata Hari turned into a real costume parade”. He also knew straight away that he wanted to give his own interpretation of the various fashion silhouettes. “I did use historical elements, but always with a twist. I wanted to create a lighter, more contemporary look. Light in the sense of weight – after all, people have to dance in the costumes – but also light in appearance. I used lots of transparent fabrics”. And he wanted to keep the lines of his designs as pure as possible; almost graphic, without detracting from the theatrical expressiveness. “I wanted to get to the essence of each silhouette, as it were. So no frou-frou and frills. That’s better for the dancers as well. If you’ve danced yourself, as I have, you always think about how a costume feels when you have to jump and turn in it, or be lifted”.

VISUAL JOURNEY

In addition, says Cherpin, the designs are of course influenced by the various countries Margaretha Zelle lived in and where she performed as Mata Hari. “As a creative team, we wanted to take the audience on a visual journey, with a strong cinematic quality. So each phase of her life was given its own look and palette of colours. For her younger years in the Netherlands, I chose subdued, monochrome colours: soft grey and lilac, in reference to Dutch landscapes and skies. For her time in Indonesia, I went for light shades and colonial white. And I portrayed Mata Hari’s triumphant years in Paris with an explosion of colour, in the style of the Moulin Rouge, which she visited regularly”.

In Act 2, the colours become gradually darker, says Cherpin. “The spirit of the times changed. During World War I, family values regained importance. Women were expected to wait at home till their husbands returned from the front. Mata Hari’s sensuality and mystery meant that she didn’t fit in. World War I was her downfall”.

FANCY DRESS PARTY

The principals who alternate in dancing the title role in Mata Hari are really put to the test, says Cherpin, also with regard to their costumes. “They wear no fewer than ten different designs, and the look changes regularly as well”. But the dancers barely have time to go to their dressing room in between the scenes. “The main character of Mata Hari is on stage practically all the time. Sometimes, she shoots off into the wings, where a small dressing room has been set up for her. But sometimes she actually changes on stage – and occasionally even while dancing”.

Text: Astrid van Leeuwen