Der Rosenkavalier

Performance information

Voorstellingsinformatie

Performance information

Duration

4 hours and 20 minutes, including 2 intervals

The performance is sung in German.

Dutch subtitles based on the translation by Thomas Graftdijk.

English subtitles courtesy of Jonathan Burton.

Comedy for music in three acts

Makers

Libretto

Hugo von Hofmannsthal

Conductor

Lorenzo Viotti

Director

Jan Philipp Gloger

Set design

Ben Baur

Costume design

Karin Jud

Lighting design

Bernd Purkrabek

Dramaturgy

Klaus Bertisch

Sophie Becker

Cast

Die Feldmarschallin Fürstin Werdenberg

Maria Bengtsson

Der Baron Ochs auf Lerchenau

Christof Fischesser

Octavian

Angela Brower

Herr von Faninal

Martin Gantner

Sophie

Nina Minasyan

Jungfer Marianne Leitmetzerin

Iris van Wijnen

Valzacchi

Marcel Reijans

Annina

Eva Kroon

Ein Polizeikommissar

Scott Wilde

Haushofmeister der Feldmarschallin

Erik Slik

Haushofmeister bei Faninal

Ian Castro*

Ein Notar

Alexander de Jong

Ein Wirt

Lucas van Lierop

Ein Sänger

Angel Romero

Drei adelige Waisen

Dana Ilia**

Maria Kowan**

Marieke Reuten**

Eine Modistin

Tomoko Makuuchi**

Ein Tierhändler

Richard Prada**

Vier Lakaien

François Soons**

John van Halteren**

Nicolas Clemens**

Christiaan Peters**

Vier Kellner

Frank Engel**

Jorne van Bergeijk**

Hans-Pieter Herman**

Sander Heutinck**

Hausknecht

Peter Arink**

* Dutch National Opera Studio

** Chorus of Dutch National Opera

Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra

Chorus of Dutch National Opera

Chorus master

Edward Ananian-Cooper

Nieuw Amsterdams Kinderkoor (part of Nieuw Vocaal Amsterdam)

Children’s chorus master

Pia Pleijsier

Production team

Assistant conductor

Aldert Vermeulen

Junior assistant conductor

Giuseppe Mengoli

Assistant director

Meisje Barbara Hummel

Frans Willem de Haas

Assistant director during performances

Frans Willem de Haas

Directing intern

Louky van Eijkelenburg

Rehearsal pianists

Jan-Paul Grijpink

Sandra Westphal

Amy Chang

Language coach

Miriam Kaltenbrunner

Language coach chorus

Cora Schmeiser

Assistant chorus master

Ad Broeksteeg

Stage managers

Marie-José Litjens

Wolfgang Tietze

Julia van Berkel

Emilia Caron

Artistic affairs and planning

Sonja Heyl

Orchestra inspector

Pauline Bruijn

Costume supervisor

Mariama Lechleitner

Master carpenter

Jop van den Berg

Lighting manager

Angela Leuthold

Coen van der Hoeven

Props manager

Jolanda Borjeson

First dresser

Sandra Bloos

First make-up artist

Isabel Ahn

Sound technician

David te Marvelde

Dramaturgy

Laura Roling

Jasmijn van Wijnen

Surtitle director

Eveline Karssen

Surtitle operator

Maxim Paulissen

Set supervisor

Mark van Trigt

Production management

Emiel Rietvelt

Edgar Lamaker

Chorus of Dutch National Opera

Sopranos

Ineke Berends

Lisette Bolle

Jeanneke van Buul

Caroline Cartens

Nicole Fiselier

Oleksandra Lenyshyn

Simone van Lieshout

Tomoko Makuuchi

Vesna Miletic

Sara Moreira Marques

Elizabeth Poz

Altos

Elsa Barthas

Anneleen Bijnen

Rut Codina Palacio

Johanna Dur

Yvonne Kok

Maria Kowan

Itzel Medecigo

Marieke Reuten

Carla Schaap

Klarijn Verkaart

Tenors

Thomas de Bruijn

Frank Engel

Milan Faas

John van Halteren

Raimonds Linājs

Roy Mahendratha

Tigran Matinyan

Richard Prada

Mirco Schmidt

François Soons

Julien Traniello

Rudi de Vries

Basses

Peter Arink

Bora Balci

Jorne van Bergeijk

Nicolas Clemens

Jeroen van Glabbeek

Julian Hartman

Agris Hartmanis

Hans Pieter Herman

Sander Heutinck

Matthijs Mesdag

Maksym Nazarenko

Christiaan Peters

Matthijs Schelvis

Jaap Sletterink

Vincent Spoeltman

René Steur

Nieuw Amsterdams Kinderkoor

Part of Nieuw Vocaal Amsterdam

Bram de Bree

Helena Jeremiasse

Jonathan Lever

Josephine Halsema

Liva Ririassa

Barbara Klee

Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra

First violin

Ionel Manciu

Saskia Viersen

Camille Joubert

Marieke Kosters

Valentina Bernardone

Henrik Svahnström

Sonja van Beek

Anuschka Franken

Sandra Karres

Paul Reijn

Inge Jongerman

Mascha van Sloten

Tessa Badenhoop

Hike Graafland

Tineke de Jong

Marina Malkin

Irene Nas

Derk Lottman

Julia Kleinsmann

Vadim Tsibulevsky (on-stage)

Second violin

David Peralta Alegre

Marlene Dijkstra

Margot Kolodziej

Karina Korevaar

Floortje Gerritsen

Joanna Trzcionkowska

Helena Druwé

Wiesje Nuiver

Jeanine van Amsterdam

Eva de Vries

Vanessa Damanet

Monica Vitali

Charlotte Basalo Vázquez

Lilit Poghosyan Grigoryants

Lotte Reeskamp

Marieke Boot

Jarmila Delaporte

Anna Lipkind-Mazor (on-stage)

Viola

Dagmar Korbar

Laura van der Stoep

Marjolein de Waart

Stephanie Steiner

Nicholas Durrant

Avi Malkin

Suzanne Dijkstra

Michiel Holtrop

Giles Francis

Odile Torenbeek

Marian van den Berg

Ernst Grapperhaus

Iteke Wijbenga

Maaike-Merel van Baarzel (on-stage)

Cello

Floris Mijnders

Douw Fonda

Atie Aarts

Nitzan Laster

Carin Nelson

Anjali Tanna

Nil Domènech Fuertes

Rik Otto

Pascale Went

Emma Kroon

Sebastian Koloski

Ilia Laporev (on-stage)

Double bass

Luis Cabrera Martin

Gabriel Abad Varela

Mario Torres Valdivieso

Peter Rikkers

Andreia Rosa Pacheco

Sorin Orcinschi

Larissa Klipp

Julien Beijer

Bas Vliegenthart

Nienke Kosters (on-stage)

Flute

Hanspeter

Spannring

Elke Elsen

Piccolo

Ellen Vergunst

Leon Berendse (on-stage)

Adeline Salles (on-stage)

Oboe

Jeroen Soors

Herman Vincken

Juan Pedro Martinez García-Casarrubios

Arthur Klaassens (on-stage)

Clarinet

Rick Huls

Leon Bosch

Annemiek de Bruin

Tom Wolfs

Peter Cranen

Harrie Troquet (on-stage)

Maria du Toit (on-stage)

Herman Draaisma (on-stage)

Bassoon

Margreet Bongers

Dymphna van Dooremaal

Jaap de Vries

Susan Brinkhof (on-stage)

Anke Benning (on-stage)

Horn

Fokke van Heel

Stef Jongbloed

Miek Laforce

Fred Molenaar

Christiaan Beumer (on-stage)

Wouter Brouwer (on-stage)

Trumpet

Ad Welleman

Jeroen Botma

Marc Speetjens

Gertjan Loot (on-stage)

Trombone

Harrie de Lange

Wim Hendriks

Raymond Munnecom

Tuba

David Kutz

Timpani

Marc Aixa Siurana

Percussion

Matthijs van Driel

Diego Jaen Garcia

Nando Russo

Pieter Mark Kamminga

Tom Pritchard

Sekou van Heusden

Harp

Sandrine Chatron

Marianne Smit

Celesta

Daan Kortekaas

Piano

Justyna Maj (on-stage)

Harmonium

Daan Kortekaas (on-stage)

Extras

Dick Addens Wies Berkhout

Annemarie Brandhorst

Wil Brandhorst

Andrea James Child

Frans Dam

Arjan Filmer

Liah Frank

Niels Gordijn

Sabine van der Helm

David Heyl

Rowan Kievits

Henk Melchers

Lidiane Moreira

Federica Panariello

Rowin Prins

Alexey Shkolnik

Anton van der Sluis

Alicia Verdú Macián

Mike Wijdenbosch

Laura Woolthuis

Liza Zhukova

Der Rosenkavalier in a nutshell

In het kort

In a nutshell

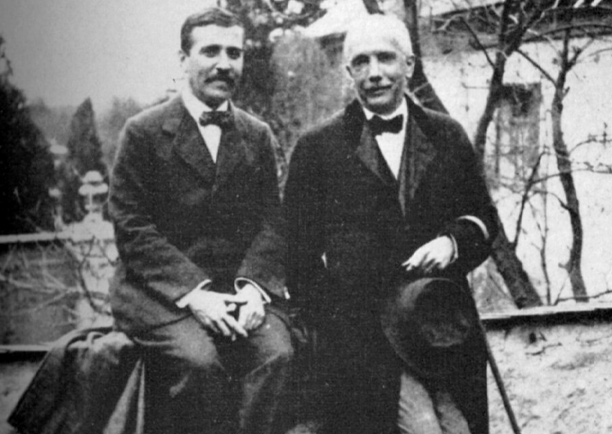

Richard Strauss and Hugo von Hofmannsthal

The artistic partnership between the German composer Richard Strauss and the Austrian poet/dramatist Hugo von Hofmannsthal is regarded as one of the most successful and productive in the history of opera. After Strauss had turned Hofmannsthal’s play Elektra into an opera (1908), their first full collaboration resulted in Der Rosenkavalier (1911). The composer and his librettist challenged one another artistically and kept each other on their toes. The artistic partnership, which lasted until Hofmannsthal’s death in 1929, produced a great variety of works that still feature in today’s core repertoire, ranging from social comedies situated in Vienna in bygone days, like Der Rosenkavalier and Arabella (1933), to the hybrid work Ariadne auf Naxos (1912) and the symbolic fairy tale Die Frau ohne Schatten (1919).

Musical synthesis

Der Rosenkavalier is seen as a turning point in the operatic career of Richard Strauss. It formed a radical break with works like Salome and Elektra, the impetuous one-acters that had made the composer an international sensation. In creating Der Rosenkavalier, Strauss and Hofmannsthal explicitly aimed to produce a work that blended different musical influences into a whole. Alongside Mozartian vocal lines, you hear Viennese waltzes from various periods, shades of Richard Wagner and 20th-century timbres.

The silver rose

In the opera, Octavian is appointed ‘Rosenkavalier’ and receives the task of handing a silver rose to Sophie von Faninal on behalf of Baron Ochs, as a token of their betrothal. In the eyes of director Jan Philipp Gloger, this silver rose embodies the core themes of the opera: “The silver rose is decadent, beautiful and very costly. At the same time, it’s also fake. It doesn’t fade, but remains eternally frozen in time. So the silver rose represents the impossible: the urge to freeze time and stave off transience. And the silver rose is also a sign of wealth and social standing; an object that few people can afford.”

The story

Follow the link below to read the story of Der Rosenkavalier.

The story

I.

In the absence of her husband, the Marschallin (Princess Marie Thérèse von Werdenberg) has spent the night with her young lover Octavian. Their idyll is rudely interrupted by Baron Ochs auf Lerchenau. Octavian disguises himself as the chambermaid Mariandl, and soon has to fend off the advances of Ochs. The penniless baron tells the Marschallin of his plan to marry Sophie, the daughter of the wealthy Faninal. He is now urgently in search of a ‘Rosenkavalier’, someone to present his fiancée with the traditional silver rose as a token of their engagement. The Marschallin suggests that Octavian, Count Rofrano, should perform the honours.

The Marschallin then receives a motley crowd of people appealing to her charitable conscience. Once alone again, she broods pensively on the passing of time. Even the return of Octavian cannot cheer her up, as sooner or later he will leave her for a younger woman.

II.

At the home of Faninal, preparations are being made for the arrival of the ‘Rosenkavalier’. On handing over the rose, Octavian and Sophie fall in love at first sight. When Ochs appears, Sophie is shocked by his churlish brashness. On no account does she want to marry him. Octavian tells the baron that he must renounce his wedding plans. The conflict between them escalates. Faninal tells his daughter she must choose between a marriage to Ochs or the convent. Ochs remains behind in delight, and when he also receives a note from Mariandl, the Marschallin’s chambermaid, his day is made.

III.

At an inn, Octavian disguises himself as Mariandl again, in order to trick Ochs. When he is alone with her, all sorts of apparitions scare the living daylights out of the baron. In terror, he calls for the police. Faninal appears too, and indignantly calls off the marriage to his daughter. When the Marschallin arrives as well, Octavian removes his disguise and Ochs flees. The Marschallin realises immediately that Octavian and Sophie are in love, and knows it is time to say farewell. The two young lovers remain behind and declare their love for one another.

Timeline

Tijdlijn

Timeline

1864

Richard Strauss is born in Munich. His father is the gifted horn player Franz Joseph Strauss.

1874

Hugo von Hofmannsthal is born in Vienna as the only child of bank manager Hugo van Hofmannsthal and Anna Fohleutner. The future poet and author grows up in sheltered surroundings and receives private education.

1882

Following university studies in philosophy, aesthetics and art history, the young Richard Strauss chooses for a career in music. This decision is prompted by a visit to Bayreuth with his father to see a performance of Parsifal.

1890

Hofmannsthal publishes his first poems under the pseudonyms ‘Loris’ and ‘Theophil Morren’.

1903

Hofmannsthal meets director Max Reinhardt, for whom the writer produces his own free adaptation of Sophocles’ Elektra. Hofmannsthal’s Elektra is to form the basis for the opera of the same name by Strauss.

1905

Strauss’ third opera Salome is premiered in Dresden and is his first big success in the opera genre.

1909

Strauss’ fourth opera Elektra, based on the play by Hofmannsthal, is premiered. The poet and the composer become close artistic partners.

1911

Der Rosenkavalier, resulting from the first full collaboration between Strauss and Hofmannsthal, is premiered on 26 January. It is followed by Ariadne auf Naxos (1912), Die Frau ohne Schatten (1919) and Die ägyptische Helena (1928). The only Strauss opera in these years not arising from the artistic partnership is Intermezzo (1927), for which Strauss writes the libretto himself, following Hofmannsthal’s refusal.

1911

On Tuesday 29 November 1911, ten months after the world premiere in Dresden, the Dutch premiere of Der Rosenkavalier takes place in the Building for Arts and Sciences, in The Hague. For the premiere, the Residentie Orkest is conducted by Richard Strauss himself.

1929

At the funeral of his own son, Hofmannsthal suffers a heart attack and dies.

1933

Arabella, resulting from the final collaboration between Strauss and Hofmannsthal, is premiered in Dresden.

1949

After creating the operas Die schweigsame Frau (1934), Friedenstag (1936), Daphne (1937), Die Liebe der Danae (1940) and his last opera Capriccio (1942), Strauss dies at his country house in Garmisch-Partenkirchen.

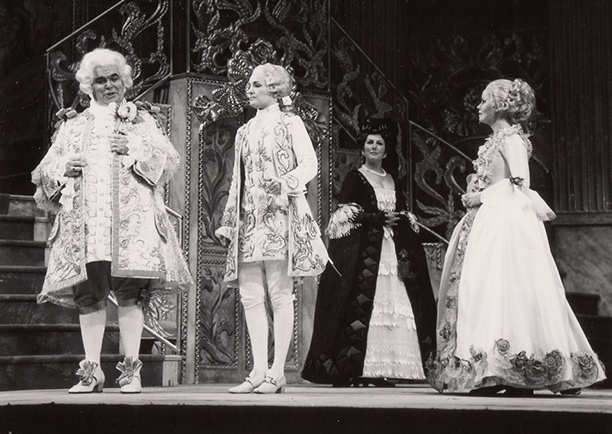

1965

On 17 November 1965, Der Rosenkavalier is the first opera production presented by Dutch National Opera, conducted by Richard Kraus and directed by Johan de Meester. The renowned Dutch soprano Gré Brouwenstijn sings the role of the Marschallin. This production is revived in 1967.

1976

On 2 June, Dutch National Opera presents a new production of Der Rosenkavalier for the Holland Festival, conducted by Edo de Waart and directed by John Cox. This production is revived in 1977, 1981 and 1987.

2004

Dutch National Opera presents a new production of Der Rosenkavalier, directed by Brigitte Fassbaender (herself renowned for her interpretation of Octavian), based on a concept by Willy Decker. The production is conducted once again by Edo de Waart. The production is revived in 2011, conducted by Simon Rattle.

2015

Dutch National Opera celebrates its 50th anniversary with a new production of Der Rosenkavalier, conducted by Marc Albrecht and directed by Jan Philipp Gloger.

2023

Jan Philipp Gloger’s production is revived by the director himself. Chief conductor Lorenzo Viotti conducts his first Strauss opera.

An interview with Jan Philipp Gloger and Klaus Bertisch

Director Jan Philipp Gloger and dramaturg Klaus Bertisch have returned to Dutch National Opera to revive their 2015 production of Der Rosenkavalier. A conversation on changing perceptions of the work and the timelessness of its central themes.

‘Der Rosenkavalier lives entirely in and through its characters and their interactions’

What does reviving this production entail?

JPG: ‘It feels like I’m truly re-creating the production. Der Rosenkavalier is an opera that lives entirely in and through its characters and interactions. Since most of the singers in the cast are new to this production, we get to flesh out the characters anew. Having other singers with different stage personalities makes all the difference. Maria Bengtsson, for instance, brings a certain bitterness to her performance, while in 2015 the girlish aspects of the character of the Marschallin were more prominent.”

KB: ‘What I like about Jan Philipp’s approach to the opera is the amount of attention he pays to detail. Especially in a work like Der Rosenkavalier, all details matter. Together they construct a bigger, layered whole.’

Jan Philipp Gloger (JPG): ‘Apart from a few minor adjustments to the costumes, the design of the production has remained the same. It’s hyper-realistic, contemporary, but at the same time situated in a timeless “now”. Looking back, I’m very happy that we opted for three “tableaux”, one for each act. It allows us to show the contrasts between rich and poor, between the social layers that run through this opera.’

Klaus Bertisch (KB): ‘In the first act, there’s the beautiful and elegant home of the Marschallin, which gives us a clear indication of her wealth and social status. This poses a stark contrast with the relative poverty of the people who visit her levée (ceremonial morning ritual, ed.). However, all that glitters is not gold. If you look more closely at the sets, you see that her windows are barred, suggesting that she may be living in a gilded cage. Then there’s the image of the second act, the wedding party in fake-baroque style that Faninal throws for his daughter. Everything there seems exaggerated, ostentatious and in bad taste. And then, in the third act, we move to a shabby hotel, which again allows us to show the difference between the poor workers and the rich people who come there for their “Viennese masquerade”.’

You’re revisiting the opera after eight years – has your perspective on the work changed?

JPG: ‘Times are changing quickly, and this has brought certain aspects of the work more sharply into focus. Awareness of structural inequality and abuse of power has significantly increased with movements like #MeToo. This means that we can’t look at Ochs’ behaviour in the innocent light we did before. He isn’t just the silly old fool, but a prototype of a toxic white man trying to abuse his power and position. He cracks bad jokes that make no one laugh, he thinks the world should bend to his will, and he chases young servant girls. Luckily, the opera gives us a lot of opportunities to put his behaviour on display critically, especially in the way other characters respond to him.’

KB: ‘In a way, our original interpretation of the opera already brought structural inequalities to the fore, such as social hierarchies and the gap between rich and poor. Some characters in Der Rosenkavalier belong to the highest ranks of the nobility and are very wealthy, such as the Marschallin and Octavian. For Baron Ochs, the situation is different. He belongs to the nobility, which puts him high on the social ladder, but financially, he’s completely destitute. That’s why he wants to marry Sophie, the daughter of Faninal, a nouveau riche who has acquired a lot of money, but doesn’t possess the grandeur of old nobility. Faninal strives for something he can’t really buy, which becomes painfully clear from the extremely decadent yet tasteless party he throws in our production. And then there is a large group of people who have neither high social standing nor money. They may not be the main characters in the opera, but they make their presence felt in every act. In the first act, they come to the Marschallin’s levée. In the second act, they are serving at Faninal’s party. And in the third act, Octavian conspires with them to rebel against Ochs.’

In your production, the silver rose is even more present than in the libretto. What does this signify?

JPG: ‘The silver rose is first of all a symbol of materialism. It’s decadent, beautiful and very expensive. At the same time, it’s also fake. Unlike real roses, the silver rose lasts forever and represents the attempt to preserve and conserve what is about to fade. In that sense, it’s closely connected to a very important topic in the opera: that of vanity, in the sense of transience. Everything is governed by time, nothing is eternal. It’s a fact of life, and the opera presents two ways of dealing with it. On the one hand, there’s the Marschallin, who is very aware of the passing of time and submits to it. “Die Zeit, die ist ein sonderbar Ding,” she says – time is a strange thing. She knows that she’s getting older, that things will change, and she commits to enjoying the present moment, knowing that it won’t last forever. Ochs, on the other hand, in a way tries to deny the passing of time. He painfully attempts to act younger than his age, and focuses blindly on the future wealth that his match with Sophie will bring him. It says a lot about him that he insists on carrying out the ceremony with the silver rose. It’s a deal: Ochs wants Faninal’s money, and Faninal wants Ochs’ status.’

KB: ‘In our production, the silver rose appears throughout the work, as do real roses, sold by street vendors. What happens in the third act is very telling. Sophie and Octavian prefer real roses to the artificial silver one. They embrace the current moment, its truth and its transience. And for the rose peddler who ends up with the silver rose, it means sudden wealth.’

The opera is a ‘comedy for music’. What’s your approach to humour, and how do you balance it out with the more tragic moments in this work?

JPG: ‘I think the humour in this opera arises from the many social situations we witness. The funny parts of the opera show us social performances by various characters who want to present themselves in a certain light. For me as a director, it’s exciting to have artists playing characters who are then in turn performing certain versions of themselves. This is where part of the humour in the piece lies. I also think it’s important that there is this potential for identification: we can all recognise aspects of ourselves in the different characters, depending on where we are in life, and what our outlook and attitude are like.’

KB: ‘There are so many different layers and interests at play in the social interactions in the opera, and as audience members, we know and see more than the characters in the opera do – that’s also why certain moments can be so funny.’

At the same time, there are moments of heart-rending beauty in the opera, such as the presentation of the rose, and the final trio and duet of the opera.

JPG: ‘Yes, and I believe these are often the moments that opera-goers long for when they come to a performance of Der Rosenkavalier. But these moments only work because the overall dramaturgy of the opera is so strong. Surrounding these “musical islands”, these isolated moments of sheer beauty and emotion, are high-energy scenes of human interaction, struggle and chaos. Without this structure, these scenes wouldn’t have such an impact.’

Hofmannsthal carefully constructed the language of Der Rosenkavalier to sound archaic rather than contemporary. How did you deal with this?

KB: ‘We treated it as an integral part of the work. Even for audiences at the world premiere of the opera in 1911, this was a language that felt distant, like it was a hundred or even two hundred years old at least. What Hofmannsthal and Strauss were doing was taking a step back in time, actively making the opera “historical”, without losing sight of the timeless aspects. In our production of Der Rosenkavalier, language is also very closely connected to the social performances that are given by the various characters. In the second act, for instance, we feel that Sophie, who comes from a bourgeois background, is trying her best to learn to speak the affected language of the nobility.’

JPG: ‘As a director who mostly works in theatre, I always tell my actors that language is not always the expression of an inner feeling, but rather an attempt to cope with an inner feeling. And that’s also how I approach the language of Der Rosenkavalier.’

If we look at the libretto, the Marschallin is only 32 years old and already considers herself middle-aged. Ochs can’t be much older than she is. Octavian, on the other hand, is just 17. How has this impacted your approach to the work?

JPG: ‘We need to keep in mind that Strauss and Hofmannsthal set their work in 18th-century Vienna, when middle and old age came much sooner in life. So, we have chosen to present characters that are roughly the same age as the singers who interpret them.’

KB: ‘And the pressure to look a certain way, to stay young, is not exclusively something for “women of a certain age” anymore. In today’s world, cosmetic surgery is virulent, not only among people who are getting older, but also among young people. Our notions of age and beauty have changed.’

How are we to interpret the happy ending for Octavian and Sophie? Hofmannsthal himself stated that their love probably wouldn’t last.

JPG: ‘I am not one of those cynical directors who doesn’t believe in love. The moment Sophie and Octavian share at the end of the opera is genuine and real, even though I know that their relationship is probably not going to stay like this forever. If anything, that’s what the opera tells us: everything will fade and nothing is eternal – but it can be true, and real and big in the moment.’

Text: Laura Roling

Continuing a tradition

Follow the link below to read more about the music of Der Rosenkavalier.

Continuing a tradition

The music of Der Rosenkavalier

Despite the intensive work it required, composing Der Rosenkavalier represented something of a respite for Richard Strauss. For one thing, this is apparent from the relatively short time it took him to compose the work (Strauss received the libretto for the first act on 4 May 1909, and on 26 September 1910 the music was finished). In contrast to the three one-act works that had preceded it [Feuersnot, Salome and Elektra, respectively, ed.], Der Rosenkavalier consisted of three long acts. Whereas the allure of Salome and Elektra lay in their tempestuous ferocity, this time Strauss took pleasure in lovingly dwelling on the individual details of each of the three major acts.

The characters that populate Der Rosenkavalier are sharply drawn with the help of leitmotifs and the evocation of certain associated moods. The least fully realized figure in this regard is Sophie, whose characterization suffers somewhat on account of the changes made to the second act. For Hofmannsthal, however, she was never meant to be anything but a pretty, respectable and above all average girl who helps to fulfil the destiny of the Marschallin. (‘The very fact that Quinquin falls for this perfectly ordinary girl in this crisscrossing double affair is the joke that makes the work a unified whole and ties together the two strands of the plot,’ the poet wrote on 12 July 1910).

Octavian is a rather more independent figure than Sophie, with his pointed leitmotif which opens the opera and reappears throughout the work, but ultimately, he too is principally illuminated by the reflected glow of the Marschallin. And despite his own distinctive leitmotif, Sophie’s father Faninal essentially serves only to contribute to the buffo mood.

Waltzes

The plot is carried by the Marschallin, even though she does not appear in the second act, and Baron Ochs. It is clear from the correspondence between Strauss and Hofmannsthal that Ochs was the composer’s favourite and the Marschallin the poet’s. In fact, the working title of the opera was Ochs auf Lerchenau, and on 2 May 1910, Strauss wrote: ‘As for the title? My preference is Ochs!’

The point where these two fundamentally different figures intersect is the prevailing Viennese atmosphere – musically speaking: the waltz. On the one hand, this keeps Ochs from becoming too vulgar in Strauss’s hands, and on the other, it ensures that the Marschallin is not overly refined, in psychological terms – not an unthinkable possibility, given Hofmannsthal’s tendencies. Strauss had used waltzes in earlier works, but nowhere does he explore every gradation of this dance form as fully as in his score for Der Rosenkavalier. In terms of their expressive qualities, they range from the polished, graceful waltz in the breakfast scene of Act I to Baron Ochs’ rather coarse favourite waltz. In between, there is a plethora of waltz music, right from the first act, even though it is the third act where they abound most fully. Often the waltz rhythm continues on in the background of the dialogue scenes, without ever turning into a distinct dance tune. For example, the scene between Octavian and Sophie following the presentation of the rose is built entirely on this rhythm.

Even Octavian’s leitmotif occasionally assumes the rhythm of a waltz. On the other hand, it is telling that the Marschallin only falls under the spell of the waltz when she is in the company of others; in her big scene at the end of act one, the waltz rhythm does not appear at all.

Mozart and Wagner

In a letter from Hofmannsthal from October 1908, the poet mentions Strauss’ intention to adhere to the model of pre-Wagnerian opera, distinguishing between self-contained ‘numbers’ and recitative passages, and indeed he mostly achieved that aim. Der Rosenkavalier contains a few pieces that can plainly be regarded as ‘closed forms’, for example the Italian tenor’s aria in the first act, as well as the trio and the duet in the third act. Regarding the latter, Hofmannsthal wrote on 6 June 1910: ‘Moreover, I have succeeded in placing the entire psychological content of the ending in numbers, duets or trios, with the exception of some very short parlando passages. That works perfectly, since the final act is not only the funniest, but also the one with the most “songs”. For the very last duet, between Quinquin and Sophie, I was tied to the verse chart you gave me, but I actually quite liked being forced to follow a melody. There’s something Mozartian to it, and a departure from that intolerable and endless Wagnerian bellowing about love.’

At the same time, the opera also contains pure parlando recitative passages, for example in the dialogue between Ochs and the Marschallin in act one and during the interrogation scene in act three, in which the orchestra is mainly there to support the singers and thus plays a secondary role. With these two extremes, Strauss finds a link to the pre-Wagnerian ‘number opera’. In many scenes these two extremes grow closer to each other, albeit in a somewhat tempered form. Just as Hofmannsthal – despite the historical framing – managed to produce a modern comedy of manners instead of a true opera buffa, the composer, too, succeeded in creating a synthesis of old and new, while preserving the continuity of musical development.

Fritz Gysi is right when he says in his Strauss biography: ‘Not Wagner and not Mozart, but Richard Strauss!’, though it should be added: ‘Richard Strauss, yes, but on the shoulders of his great forebears.’ Wagner’s influence is also unmistakable in Der Rosenkavalier. To begin with, there are the parodic echoes and quotations, such as the climactic Tristanesque ‘build-up’ in the introduction (which the score indicates is to be played ‘durchaus parodistisch’) and the use of Tristan’s ‘day’ motif for Octavian’s words ‘Warum ist Tag?’ in the first act. And in broader terms, the piece still outwardly resembles a dramatic symphonic opera in the Wagnerian mould. Here, though, the leitmotif has largely been stripped of its deeper psychological dimensions, having been reduced to the simple principle of a pre-Wagnerian reminiscence motif.

Tradition and innovation

The singing in the major dramatic scenes usually proceeds in a light, conversational tone; but the orchestra, which holds entire sections together by solidly formed motifs, creates an impression of alternating between recitative and self-contained forms. This is the case, for example, in the big scenes between the Marschallin and Ochs at the end of the first and second acts, as well as in the scene featuring the presentation of the rose. The unifying element in these instances is often the waltzes. At times the singing voice is drawn into the melodic line of the orchestra at the end of phrases. By blending this quasi-closed form in the orchestra with quasi-recitative in the singing voice, Strauss manages to combine the principle of dramatic symphonic opera, the prevailing form of the 19th century, with the pre-Wagnerian number opera, the old opera buffa, whose spirit animates Der Rosenkavalier.

At the same time, however, after the harmonic excesses of Elektra, which at times verged on atonality, this opera represents a return to the more restrained sound and tonal harmonies of the past. In accordance with established operatic tradition, the cantabile melody again comes into its own, even though it is not necessarily always voiced by the singers. The orchestra has been reduced in size and calibrated in such a way that it does not drown out the singing voices. At the same time, however, it has not lost the clarity and expressiveness it acquired in Salome and Elektra; the most striking example of this can be found in the scene depicting the presentation of the rose.

In musical terms, Hofmannsthal’s ‘Komödie für Musik’, a modern comedy of manners in baroque attire, was at the time of its composition a completely new combination of dramatic symphonic, Wagnerian technique and pre-Wagnerian opera. In terms of both the dramatic material and the music, Strauss hit upon new ways for him and his fellow early 20th-century opera composers to break free of Wagner’s influence. The frequent mention of pre-Wagnerian examples in the correspondence between the two artists should definitely not be seen as historicising. As Der Rosenkavalier clearly shows, it was by no means their intention to resurrect an old genre and thereby turn back the clock; nor did they wish to break with tradition. Rather they sought to breathe new life into that tradition by taking their cue from older examples. The fact that they succeeded in doing so with Der Rosenkavalier is evident from the work’s epoch-making success.

Text: Anna Amalie Abert

Translation: Steve Leinbach

Unwritten afterword to Der Rosenkavalier

In March 1911, two months after Der Rosenkavalier had its world premiere in Dresden, the Austrian magazine Der Merker published an ‘Unwritten Afterword’ by Hugo von Hofmannsthal. In it, the poet shares his thoughts on the way in which his collaboration with the composer Strauss constitutes a unified whole, on how the characters were shaped and on the way in which the piece brings together past and present.

Unwritten afterword to Der Rosenkavalier

A work is a whole; even a work produced by two people can become a whole. Contemporaries have much in common, even their most personal qualities. Threads run back and forth, and related elements rush to intermingle. Anyone who tries to separate them out is doing an injustice. Anyone who singles out one thing at the expense of another forgets that the totality always shines through, unnoticed. The music must not be torn from the text, nor the word from the animated image. This work was made for the stage, not for the printed page or for the individual at his piano.

Man is infinite, while a puppet is narrowly limited; there is much that flows back and forth between people, while puppets stand in neat opposition to each other. The dramatic figure always exists somewhere between these two poles. The Marschallin is not there for herself, nor Ochs for himself. They are opposites, and yet they belong together. The youth Octavian stands between them and serves to link them. Sophie faces the Marschallin – the girl versus the woman – and once again it is Octavian who stands between them; he both separates them and connects them. Like her father, Sophie is profoundly bourgeois, and this group stands in contrast to the nobility, the powerful, who can get away with a lot. Ochs – however he may behave – is still a sort of nobleman; he and Faninal complement each other. One needs the other, not only in this world but also, as it were, in a metaphysical sense. Octavian draws Sophie to him – but is his hold on her truly eternal? There is some cause for doubt. This is how groups stand in opposition to one another: those who are joined are separated, while those who are separate are joined together. They all belong together, and what is best lies between them: it is immediate yet eternal, and it is here that there is space for music.

One might have the impression that it must have taken a great deal of effort to conjure up a bygone era, but that is merely an illusion, which could not stand up to more than an initial cursory glance. The language of the characters is not to be found in any book; yet it hangs in the air even now, for there is more of the past in the present than one might suspect. Nor are the Faninals, the Rofranos, the Lerchenaus of the world extinct, though their servants do not stroll around today in such magnificent colourful uniforms. The manners and customs that seem fabricated are real and rooted in tradition, and the manners and customs that seem real are fabricated. In that respect, too, there is a living whole. You can’t deprive the characters of their mode of speech, for the two emerged at the same time. It is colloquial language, perhaps more so than elsewhere in the theatre, but it does not seek to be the sole medium from which all life flows into the characters, but rather, to do so in tandem with the music. Where language seems to be at odds with the music, it may not be entirely unintentional; where it completely surrenders to the music, it happens from within.

Music is infinitely loving and binds all things together: as far as the music is concerned, Ochs is not obnoxious – the music senses what lies below the surface. To the music, his satyr’s face and Rofrano’s youthful countenance are only alternating masks, from which the same eyes peer out. To music, the Marschallin’s sorrow is as sweet and melodious as Sophie’s childlike joy. Music has only one purpose: to allow the harmony of all living things to flow forth, to the joy of all souls.

Text: Hugo von Hofmannsthal

Translation: Steve Leinbach

Programmaboek

BECOME A FRIEND OF DUTCH NATIONAL OPERA

Friends of Dutch National Opera support the singers and creators of our company. That friendship is indispensable to them and we are happy to do something in return. For Opera Friends, we organise exclusive activities behind the scenes and online. You will receive our Friends magazine, have priority in ticket sales and a 10% discount in the Dutch National Opera & Ballet shop.