‘Exoticism’ dictated her early career – she was sometimes dressed as a bird, locked in a cage, singing of her ‘home’ in Africa (‘Afrique’), even though she wouldn’t set foot there until later in life. Some may view this as exploitation, and there’s no escaping that fact. But I believe that for Joséphine Baker, it was the first time she could reveal herself in front of an audience on her own terms. Even that initial image I had of her in a banana skirt is a powerful one of agency – a female force at the center of a crude representation of male dominance.

While many speak of Joséphine’s larger-than-life presence through the lens of performance, I think her impact was most beautifully realized through her involvement in France’s resistance movement during World War II. Recognition from her home country wasn’t confirmed until the Civil Rights Movement, when Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. invited her to speak at the March on Washington in 1963, and when Coretta Scott King asked her to be the face of the movement after King’s assassination.

So, to say she was turned into an icon would not be an overstatement. But for me Joséphine Baker is not merely an icon for women. She is not just an icon for Black people. She is an icon of liberty. She challenged and combated her environment through various modes of expression. In music, however, she was limited in terms of experimentation. She left the United States just as the Harlem Renaissance was coming into full bloom, and mostly worked as a vaudevillian dancer early on. She never learned to sing the blues and missed the beginning of the jazz age; although she flourished in the stylings of the French music hall — a neatly, confined frame, where she could push boundaries without being too explicitly confrontational.

I first programmed songs Joséphine was known for on a 2014 debut recital program. These songs touched on themes which seemed to pervade her life – exploitation and objectification, issues surrounding identity, the difficulties in maintaining intimate relationships, and the roles that she played — from an exotic entity in a foreign place to a charmer, nurturer, and activist.

The director Peter Sellars then encouraged me to broaden my exploration of Baker and her influence on me as a performer. So, Peter invited the poet Claudia Rankine to contribute text; I felt it pertinent to consider Baker’s body through dance, so Peter asked the choreographer Michael Schumacher to develop a deconstructed charleston with me; and the International Contemporary Ensemble introduced me to the composer Tyshawn Sorey. Together we compiled words, movement, and music that examined and highlighted various undercurrents of Joséphine Baker’s life, in an effort to share an in-depth portrait of a dynamic being.

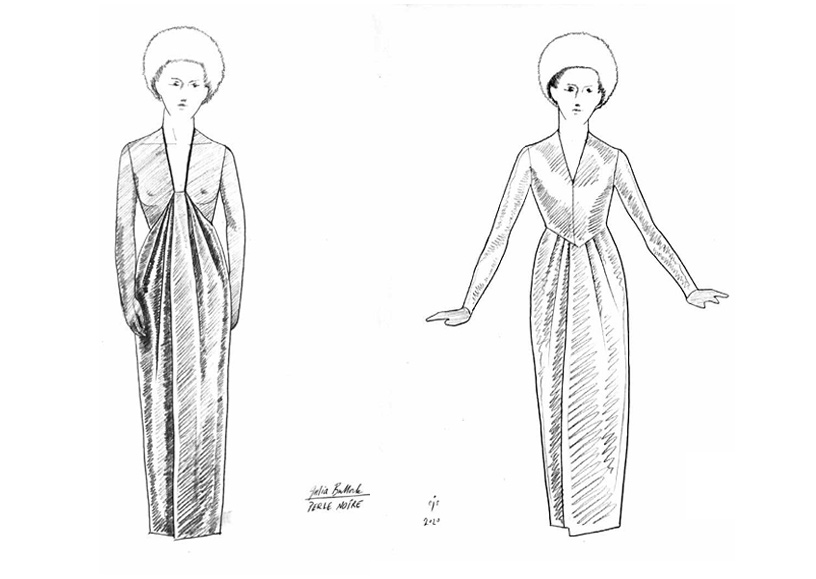

In 2016, after performing the source material in a relatively raw form called Josephine Baker: A Portrait. Tyshawn and I retitled the work into Perle Noire: Meditations for Joséphine. This project was in fact not so much about her; it was actually a work especially for her. We’ve since shared Perle Noire: Meditations for Joséphine in a wide range of venues across the United States – from outdoor theaters and cabaret settings to museums of visual art. Each time we return to this piece, it presents us with new opportunities to collectively reexamine the material and to investigate how to more pointedly share why the themes permeating Baker’s story still resonate today.

To share our Perle Noire for the first time in Europe and in an operatic space carries significance for me, not only because I am now a permanent resident in Germany, but also because Baker had fled the United States with the hope to escape racism, various other forms of oppression and live with more freedom. However, despite her status and privileges as an extraordinary performer, she still had to reckon with the reality that dehumanizing, colonialist practices and attitudes were still unresolved across Europe… a place where she so wanted to feel safe and that she wanted to call home.