Tchaikovsky was not the most obvious candidate for Vsevolozhsky to approach. Although he was a celebrated composer with regard to symphonies, Tchaikovsky had little understanding of ballet music, according to the norms of the day. His first ballet composition, Swan Lake, turned out to be a flop in 1877. Fortunately, Vsevolozhsky recognised the composer’s special qualities, and it was only after Tchaikovsky accepted the commission that Vsevolozhsky asked Marius Petipa to create the choreography. That choice was more or less self-evident, as the Frenchman had already been working at the Imperial Ballet of the Mariinsky Theatre since 1847 – first as a soloist and later as a teacher and choreographer – and was held in high esteem.

Together with Petipa and Tchaikovsky, Vsevolozhsky – who wrote the libretto and designed the sets and costumes – made The Sleeping Beauty a tribute to Tsar Alexander III. By referring to the court of Louis XIV, the makers put the tsar’s court on a par with the splendour with which the French Sun King surrounded himself. Nevertheless, the remarks of Alexander III after watching the dress rehearsal remained restricted to ‘very nice’. The critics found the ballet ‘far too serious’, writing that the work had ‘no plot’ and was ‘not a ballet, but a fairy tale; one big dance divertissement’. They thought Tchaikovsky’s music was ‘too symphonic and heavy’. The audience, however, were very enthusiastic about The Sleeping Beauty.

SLEEPING BEAUTY COMES TO THE WEST

Among that audience was the Russian impresario Sergei Diaghilev. Although The Sleeping Beauty had already been danced in 1896 in Milan, it was Diaghilev who brought the production to the attention of the wider Western audience in 1921. For his production,he called on Nikolai Sergeyev, the former director-general of the Mariinsky Theatre, who had fled to the West following the October Revolution, taking with him books containing the notation of the original choreography of The Sleeping Beauty, The Nutcracker and the Petipa/Ivanov version of Swan Lake. So Diaghilev’s company Les Ballets Russes was able to present a production that was more or less identical to the original version. However, we cannot know the extent to which Sergeyev had adapted the original. And neither is there total certainty about the originality of the music used. There was no complete score of Tchaikovsky’s composition to hand in 1921. The composition was rewritten on the basis of reduced piano scores by Igor Stravinsky – a great admirer of Tchaikovsky’s Sleeping Beauty.

The huge cost of The Sleeping Princess, as Diaghilev christened his production, nearly brought the company to its knees. But it was due to Diaghilev’s efforts that interest in the ballet was aroused in the West. From then on, various companies began to stage their own versions of the story. The two most legendary productions are the 1939 version by Nikolai Sergeyev for the Vic-Wells Ballet (now The Royal Ballet) and the one created by Bronislava Nijinska (former dancer with Les Ballets Russes) and Sir Robert Helpmann in 1960 for the company of the French Marquis de Cuevas (the latter production did lead to the bankruptcy of that company).

A RELENTLESS BALLET

There are some people today who dismiss The Sleeping Beauty as a ballet cliché. Yet the companies, choreographers and dancers who do recognise the value of Petipa’s original are still in the majority by far. For them, The Sleeping Beauty is the unsurpassed highlight of the French-Russian dance style. The rich dance vocabulary, the long, graceful lines that accentuate the elegance of the performers, the musicality of the choreography and the belief in purity and perfection that is radiated by the production as a whole make the ballet the most flawless and successful example of Petipa’s art. The narrative element is of secondary importance. The goals aimed for by Petipa were the display of elegant, delightful dancing and sparkling virtuosity, rather than the expression of emotions. His dance gems, mostly set in taut, straight patterns, are therefore reminiscent of hard, glittering diamonds. Such cool, clear choreography leaves little room for covering things up, which makes The Sleeping Beauty a relentless ballet to perform. The almost supernatural demands made on the dancers mean it is still regarded as the touchstone of the classical ballet repertoire today.

SIR PETER WRIGHT’S VERSION

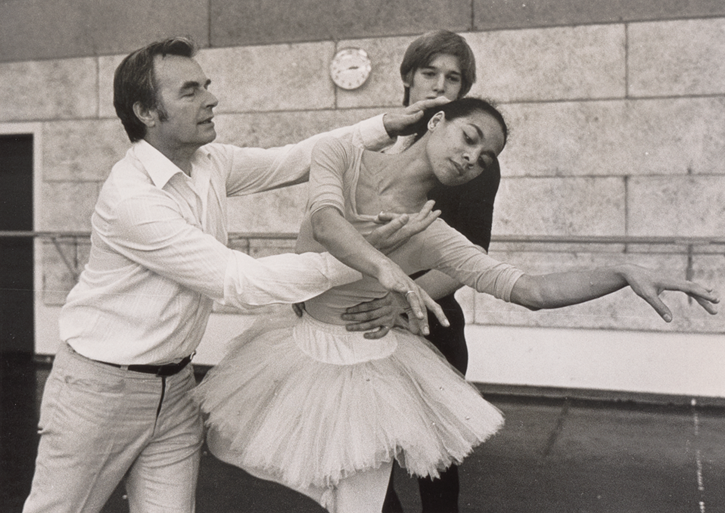

Dutch National Ballet danced its first complete Sleeping Beauty in 1968, in a version by the Polish choreographer Conrad Drzewiecki. Four years later, the ballet was staged by Ronald Casenave, who based it on the production by Le Grand Ballet du Marquis de Cuevas. Neither version stayed in the repertoire for long, unlike the third version presented by Dutch National Ballet in 1981, by the Englishman Sir Peter Wright.

Wright’s Sleeping Beauty is Petipa at his best. The production has all the radiance, lustre and allure that the imperial ballet master had in mind. Although Wright has remained faithful to tradition, he believes it is impossible to dance The Sleeping Beauty as it was danced a hundred years ago. “Today’s audiences would be bored to tears. So paradoxically you have to adapt the ballet if you want to do justice to tradition.”

Philip Prowse – the designer of the breathtaking sets and costumes – situated the story at the French court of the seventeenth and eighteenth century. The fashions of the time are reflected in the costumes and their rich details, and the scenery exudes a magnificence that appears to come straight from the Mariinsky Theatre. Wright and Prowse breathed new life into The Sleeping Beauty and preserved the glittering legacy of Marius Petipa for modern audiences today.

Author: Astrid van Leeuwen

With thanks to Yvonne Beumkes and Bert Westra