Four Temperaments

Preface

Voorwoord

Muziek als gemene deler

Welcome to Dutch National Ballet’s new season! We hope you’ve had a great summer and we’re looking forward to seeing you in our theatre again.

We’re opening this season with Four Temperaments: four works by choreographers from four different generations. In their works, these choreographers each share their own vision of ballet, with one common denominator: they all enter into a close relationship with the music to which they created these works. Starting with George Balanchine, who took a composition by Paul Hindemith as the starting point for his groundbreaking The Four Temperaments. This iconic work, which occupies an important place in twentieth-century ballet history, has lost none of its thrill and still intrigues today’s audiences and dancers.

Hans van Manen also based his internationally famed Frank Bridge Variations on a piece of music with almost the same name: Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge by Benjamin Britten, one of the greatest British composers of the twentieth century. Van Manen succeeds in giving each of the short variations in the composition its own colour and atmosphere, and thus conjuring up a totally different world every time. This is one of the reasons that Frank Bridge Variations is regarded as a true masterpiece.

Alongside these two famous and popular ballets, we’re presenting two world premieres in Four Temperaments. The first is by myself: The Chairman Dances, a work for a large ensemble to the music of the same name, by the American composer John Adams. The piece was originally composed for the opera Nixon in China, but it is real dance music, which is precisely what inspired me to choreograph to it. The programme closes with a second world premiere, by our former Young Creative Associate Juanjo Arqués. Full Frontal is about the stress we are experiencing more and more often in today’s society. These feelings of stress are reflected in and reinforced by Michael Gordon’s composition Weather One, to which Arqués created his latest work.

Together, these four works give an interesting view of what ballet can be: a language, an expression of emotions and a pure and powerful interpretation of music.

I hope you enjoy this varied and swinging start to Dutch National Ballet’s season!

Ted Brandsen

Director Dutch National Ballet

Credits

Credits

Credits

The Four Temperaments

Choreography

George Balanchine

Music

Paul Hindemith - The Four Temperaments: Theme with Four Variations for String Orchestra and Piano (1940)*

Piano

Ryoko Kondo

Lighting design

Jan Hofstra

Howard Eldridge

Staging

Patricia Neary

Ballet master

Guillaume Graffin

World premiere

20 November 1946, Ballet Society, New York

Premiere at Dutch National Ballet

17 september 1961, Stadsschouwburg Amsterdam

(now: Internationaal Theater Amsterdam)

Duration

circa 30 minutes

*Music Published / Licensed by: © Schott Music, Mainz / Albersen Verhuur B.V., ’s-Gravenhage

The Chairman Dances

World premiere

Choreography

Ted Brandsen

Music

John Adams – The Chairman Dances (1985)

Costume design

François-Noël Cherpin

Lighting design

Wijnand van der Horst

Ballet master

Larissa Lezhnina

World premiere at Dutch National Ballet

16 September 2023, Dutch National Opera & Ballet, Amsterdam

Duration

circa 12 minutes

Frank Bridge Variations

For Sol and Paul

Choreography

Hans van Manen

Music

Benjamin Britten - Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge, opus 10 (1937): Introduction and Theme, Adagio, March, Bourrée Classique, Wiener Walzer, Moto Perpetuo, Funeral March, Chant, Fugue and Finale*

Set and costume design

Keso Dekker

Lighting design

Bert Dalhuysen

Ballet masters

Rachel Beaujean

Jozef Varga

World premiere at Dutch National Ballet

18 March 2005, Dutch National Opera & Ballet, Amsterdam

Duration

circa 24 minutes

*Music Published / Licensed by: © Boosey & Hawkes, Londen / Albersen Verhuur B.V., ’s-Gravenhage

Full Frontal

World premiere

Choreography

Juanjo Arqués

Music

Michael Gordon – Weather One (1997)

Set and costume design

Tatyana van Walsum

Lighting design

Yaron Abulafia

Sound design

Ian Dearden

Libretto/dramaturgy

Fabienne Vegt

Assistant to the choreographer

José Carlos Blanco

World premiere at Dutch National Ballet

16 September 2023, Dutch National Opera & Ballet, Amsterdam

Duration

circa 21 minutes

Musical accompaniment

Dutch Ballet Orchestra conducted by Matthew Rowe

Set, lighting and sound

Technical department of Dutch National Opera & Ballet

Production manager

Anu Viheriäranta

Stage managers

Kees Prince

Wolfgang Tietze

Set supervisor

Sieger Kotterer

First carpenter

Peter Brem

Lighting managers

Michel van Reijn

Angela Leuthold

Lighting supervisor

Wijnand van der Horst

Follow spotters

Carola Robert

Marleen van Veen

Famke van der Marel

Hein Hazenberg

Anton Shirkin

Follow spotters coordinator

Ariane Kamminga

Sound engineers

Arnout Verdonk

Costume production Frank Bridge Variations

Kostuumafdeling Het Nationale Ballet

Costume production The Chairman Dances

Atelier Martine Douma

Costume production Full Frontal

Costume department of Dutch National Ballet in collaboration with Renske Kraakman

Assistant costume production

Eddie Grundy

First dresser

Andrei Brejs

Introductions (in Dutch)

Jacq. Algra

Totale voorstellingsduur

circa 2 hours and 25 minutes, including 2 intervals

‘Without ears, you don’t see anything’

Hans van Manen about George Balanchine

Hans van Manen about George Balanchine: ‘Without ears, you don’t see anything’

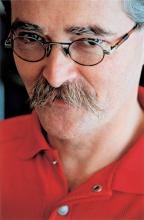

In the early fifties – when Hans van Manen was still a dancer – he saw his first ballet by George Balanchine, and it was love at first sight. “From then on, every Balanchine ballet scored ten out of ten for me!” And the Russian-American great master, who passed away in 1983, still regularly looks over Van Manen’s shoulder. “For me, he’s the greatest – and always will be. But I do occasionally say, ‘And now you can clear off!’”

“I think Concerto barocco was the first ballet. No, actually I’m sure it was. I saw it in the Stadsschouwburg, in Amsterdam”, says Hans van Manen about his first Balanchine experience. “At the time, I’d probably just started dancing with the Ballet of the Nederlandse Opera, which had an extensive repertoire, but I knew immediately that this was of a totally different order! I was bowled over straight away. What struck me most was that everything was so clear. And then the way he used the group of dancers, getting two women to dance a duet – in those days already – and how musical the whole choreography was. At the time, I was already familiar with Bach’s Double Violin Concerto, and everything fitted perfectly. During that one performance, I immediately comprehended forever that a great master was at work here.”

Tongue-tied

That same week, Van Manen waited for the choreographer and artistic director of the recently founded New York City Ballet in the dressing room corridor of the Stadsschouwburg. “Just for something to say, I asked him how I could join his company as a dancer. To which he answered, very matter-of-factly, ‘You’ll have to come to the US and audition.’” But that never happened, says Van Manen. “Like Balanchine, I wanted to become a choreographer, and I didn’t see myself doing that in America. Not just because of the huge competition there, but also because I wanted to belong to one group, and there was much more opportunity for that in the Netherlands.”

Later, he says, he did meet Balanchine again on several occasions. Like in the seventies, when Wiener Staatsballett was dancing Balanchine’s Brahms-Schönberg Quartet and Van Manen’s Adagio Hammerklavier in the same programme, and director Gerhard Brunner invited the two choreographers – and other guests – to his house for dinner. Van Manen says, “I hardly dared say or ask anything. I was hugely impressed, and of course that can easily make you tongue-tied. But it was a wonderful evening nevertheless, because the conversation was great and ears are important too.”

Just too late and exactly on time

From that first introduction in the early fifties, Van Manen gave each subsequent Balanchine ballet ‘a full ten out of ten’. “Every single one is exceptional, and they’re all so fantastically different.” This meant that later, Van Manen would often say that Balanchine was always looking over his shoulder in the rehearsal studio. “That’s because”, says Van Manen, “he was ahead of me in being as clear as possible in every aspect of a ballet: in the solutions you need to find in a pas de deux, and in the way you deal with groups, etc. Without thinking about it, I learned that straight away. I immediately understood what he meant by ‘visibility’. You don’t need to understand dance at all. You read a Balanchine ballet like you read a good book: you just keep turning the pages, and at the end you’re extremely satisfied.”

Another thing that connects the two choreographers is their nerve in using a great diversity of music styles and pieces. Neither did they shy away from choosing music by Bach, for example, who – at the time – was still often regarded as ‘sacrosanct’ by music purists. Their taste did differ, however, and Balanchine once asserted that ‘the art of dance would be better off not venturing into Beethoven’s world’; an assertion that was completely overturned by Van Manen, when he choreographed Adagio Hammerklavier in 1973. Van Manen says, “Balanchine was also interested in rodeo, American folk music, Broadway and the circus. Whereas I made works to music by The Rolling Stones, James Brown and John Cage.” But something the two definitely share is their love of jazz and swing. Van Manen says, “If you see that the steps really fit the music – as in the case of Balanchine – then it swings. Swinging is being just too late and exactly on time. Then you create space between the notes as well, and that’s essential for swing.”

Humor is essential

Asked what his favourite Balanchine ballet is, Van Manen finds it hard to say, but he admits, “I do get quite excited by his Violin Concerto. You understand exactly where it all comes from. The ‘folk dance bits’ in it, the eye contact, the humour and the way Karin von Aroldingen (a dancer from the original cast – ed.) waves playfully to the others when she comes on in the finale – it’s all so ingenious.” Even in the most serious of ballets, says Van Manen, humour is essential. “As a choreographer, you have to be able to distance yourself, and humour helps with that. And anyway, every joke you tell has a grain of truth in it.”

In Van Manen’s opinion, The Four Temperaments is also a masterpiece. In the programme with virtually the same name, it precedes Van Manen’s Frank Bridge Variations. “It’s a wonderful ballet, although I can never quite explain why.” He goes on to try, nevertheless, quoting Balanchine: ‘See the music, hear the dance’. “People always think you need your eyes for ballet, but without your ears you don’t see ballet. It’s like the lift in the hallway where I live. When I’m in my apartment (quite a distance from the lift – ed.), I can ‘see’ everything. I can hear from every ‘click’ or ‘plop’ whether the lift is coming from up or down, and from which floor.”

Stealing’s okay, but imitating isn’t

However great Van Manen’s admiration, he says he’s never copied a single step from Balanchine. “His ballets were just an enormous source of inspiration. Although actually, I really hate the word ‘inspiration’. Following Picasso and Stravinsky, I prefer to say, ‘I steal wherever I can’. That means you’re allowed to steal, but not to imitate. You see something in an artwork by someone else, which that person hasn’t seen themselves, and then you take it a step further or do something totally different with it.”

And that applies not only to Balanchine, but also to other choreographers who have ‘inspired’ him. “Jerome Robbins and Martha Graham too.” And as Alexandra Radius and Han Ebbelaar remark in the recently published book Levensdans: Van Manen has certainly absorbed something of the French style and virtuosity as well, as he was formed as a dancer partly by Françoise Adret (artistic director of the Ballet of the Nederlandse Opera at the time) and danced for a brief period with Roland Petit’s Les Ballets de Paris. Van Manen says, “If Han and Lex think that, then there must be some truth in it. I’ve never been crazy about the urge the French have to tell stories in dance, but of course you always come from somewhere. You can’t progress without your past.”

So Balanchine is not the only one regularly looking over his shoulder during rehearsals, he says. “Picasso and Stravinsky do it too, and a hell of a lot of others besides. But not for the whole hour and a half. Only when you get stuck and think, ‘how would so-and-so have solved it?’ And anyway I get some pretty critical observers over that shoulder of mine. They can also start to get irritating if they’re not needed. So I have no qualms about saying ‘sod off’ once in a while! Even to the greatest master of them all – Balanchine.”

The last of the Mohicans

If Balanchine hadn’t passed away at the age of seventy-nine, would he have carried on choreographing into his later years, like Van Manen himself? “I should think so! As an artistic director, he had his own group, and then you have a responsibility to give that group new works to dance. But actually, it doesn’t matter. The fact that his ballets are still danced all over the world means he’s still at work, as it were.”

“Nevertheless, you do sometimes realise they’re no longer with us: Balanchine, Robbins, Merce Cunningham. I’m the last of the Mohicans. Even though I, too, have stopped choreographing new works. It seems the sensible thing to do. There comes a time for looking back and gaining an overview, and that’s what I’ve been doing in recent years.”

New York, New York

Balanchine’s ballets and Van Manen’s ballets are still danced worldwide, and in Van Manen’s case by an increasing number of prominent companies in recent years, including some in the United States. Nevertheless, 2022 was the first time in many years that Dutch National Ballet had performed a Van Manen ballet in New York. At the renowned Fall for Dance Festival, the maestro and the four dancers from his Variations for Two Couples were showered with thunderous applause by a rapturous audience at New York City Center, which was sold out for two nights.

Van Manen, ignoring all the success for a second, says, “There was one terrible review, where the critic talked about irons, as apparently he’d never seen that you can also do a big lift in a pas de deux close to the ground.” But he adds proudly, “The rest raved, and of course it was fantastic to stand there in front of such an ecstatic crowd. Because”, he says, “even if the New Yorkers agree that New York is no longer New York, it’s still NEW YORK!!! You realise that when you’re standing there. After all, it is – and always will be – the city my great role models came from. With Balanchine in the lead.”

Text: Astrid van Leeuwen

The Four Temperaments

Gloomy, cheerful, imperturbable and hot-headed

The Four Temperaments: gloomy, cheerful, imperturbable and hot-headed

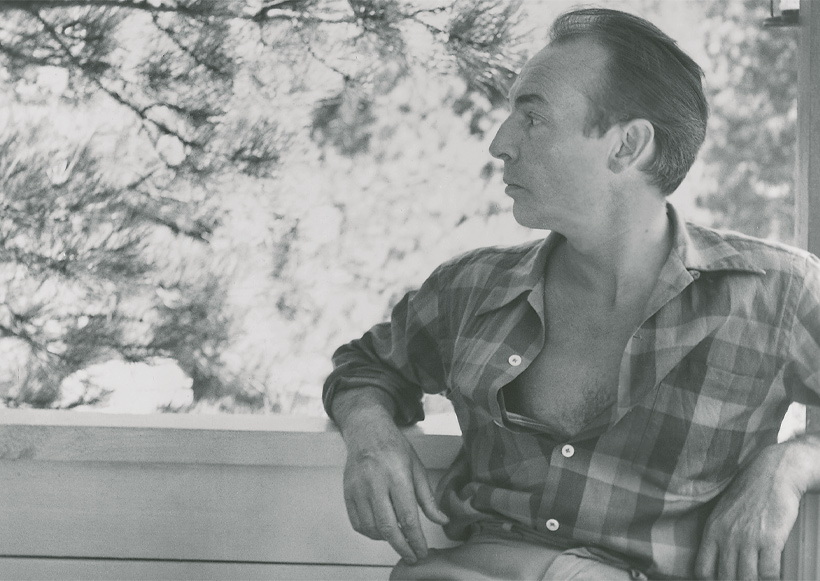

The Four Temperaments is one of the early works by the Russian-American choreographer George Balanchine (1904-1983). Besides being a key work in his oeuvre, it was also the first Balanchine ballet to be taken into Dutch National Ballet’s repertoire, in 1961. It is hard to believe it has now been around for over 75 years. The ingenious, tricky choreography that frequently crackles with energy still adds a magical dimension to Hindemith’s composition of the same name.

Balanchine created The Four Temperaments in 1946 for the opening programme of Ballet Society, the forerunner of New York City Ballet. Although the work does not tell a story, it does have a theme. As the title suggests, the ballet–like Hindemith’s music – is inspired by the Ancient Greek classification of character traits into four main types: melancholic, sanguinic, phlegmatic and choleric. Balanchine gives an abstract and subtle rendition of these ‘temperaments’ just by adding differences to the way energy is discharged in the dancing. The ballet is also a clear example of how this most important dance innovator of the twentieth century revitalised the age-old aesthetic traditions of ballet by injecting them with the dynamic vitality and swinging high spirits of American jazz dance and showdance.

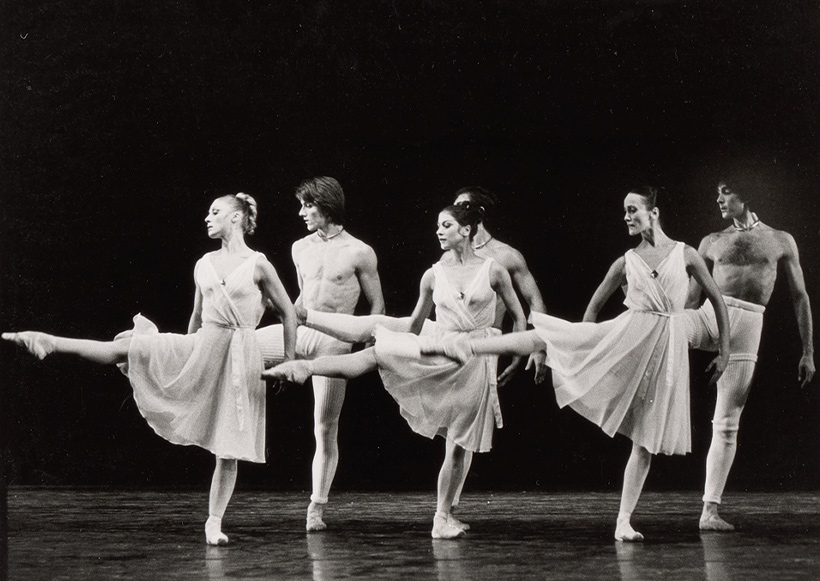

One of Balanchine’s most famous quotes is ‘Ballet is woman’, and although there are also some wonderful male roles in The Four Temperaments, the women do predominate. With their high leg extensions and pronounced hip movements, they keep rising to the surface like long-legged ‘insects’.

The opening section of the ballet, Theme, consists of three short duets, which are contemplative, fiery and lyrical in turn. This is followed by Melancholic, the first of the four temperaments, interpreted by a male soloist who is joined first by two female dancers and then by another four. The gloominess of this character is expressed by the way the dancer appears to be pulled towards the ground. Then follows the cheerfulness of Sanguinic, in flowing, energetic dance patterns for a soloist couple and four female dancers. In Phlegmatic, the imperturbability is expressed by the languid and polished interplay of lines through which a male soloist and a quartet of female dancers demonstrate Balanchine’s characteristic intertwining movements.

The last temperament is Choleric. Impatience and hot-headedness are portrayed here in a dazzling, explosive variation for a female soloist. She is soon joined by the other dancers, and a grand finale follows – featuring protracted high lifts – in which all the themes are briefly re-introduced as if to underline that different temperaments can go together very well, even within one person.

Text: Astrid van Leeuwen

A CELEBRATION OF DANCE, MUSIC AND ZEST FOR LIFE

Ted Brandsen on The Chairman Dances

A celebration of dance, music and zest for life: Ted Brandsen on The Chairman Dances

The Chairman Dances, by choreographer and artistic director Ted Brandsen was actually supposed to premiere a year ago, as part of the programme planned to open the season, Celebrate. But things turned out differently. The war in Ukraine broke out and Brandsen decided that a festive programme was no longer appropriate, and neither was the cheerful piece he had in mind for The Chairman Dances. So the title of the programme changed from Celebrate to Shadows and The Chairman Dances made way for Kurt Jooss’ The Green Table. Brandsen says, “Unfortunately, that terrible war is still ongoing. But that makes it especially important to reflect on the strength of the people who, even in the most difficult of circumstances, manage to find hope and carry on with their lives. You could see The Chairman Dances as a celebration of that strength and zest for life, and also of the joy that dance and music can bring us. I hope to be able to give the audience a bit of that feeling.”

Foxtrot for Orchestra

For The Chairman Dances, Brandsen took the music of the same name by the American composer John Adams as his starting point. The composition was originally created for Adams' opera Nixon in China, but it has now been used by many choreographers as a stand-alone piece of music. Brandsen says, “And it really is dance music. There’s good reason that the subtitle is ‘Foxtrot for Orchestra’; a reference to ballroom dancing.” This nod to ballroom dancing is reflected, in turn, in Brandsen’s choreography; a piece for ensemble, from which individuals break free now and then. “It’s as if they dance for a moment in the spotlight, like in ballroom dancing, and the others make room for them.”

Enormous momentum

The compelling character of Adams’ composition is reflected both in the choreography and in the costume and lighting designs. “The music is very inspiring. I already used it in 1998, to choreograph an occasional piece for West Australian Ballet. The composition still really appeals to me, partly for its enormous momentum. That verve is also displayed in the costumes by François-Noël Cherpin, who has been designing the costumes for all my ballets since 1990, and the colourful lighting designs by Wijnand van der Horst.

Text: Rosalie Overing

Frank Bridge Variations

Unity in constrasts

Frank Bridge Variations: eenheid in constrasten

Frank Bridge Variations is het eerste werk dat Hans van Manen voor Het Nationale Ballet maakte nadat hij in januari 2005 bij het gezelschap terugkeerde als vaste choreograaf, een functie die hij al eerder – van 1973 tot 1987 – bekleedde. Uitgangspunt voor de choreografie is de compositie Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge van Benjamin Britten (1913-1976), die het stuk schreef als eerbetoon aan zijn leermeester Frank Bridge. De compositie voor strijkorkest, waarmee Britten internationale erkenning verwierf, bestaat uit elf virtuoze, karaktervolle en soms ook parodiërende variaties op een thema dat de Engelse componist ontleende aan Bridges strijkkwartet Three Idylls. Van Manen gebruikte negen van de elf variaties voor zijn ballet (de twee andere vond hij te romantisch), waarin hij zich, ingegeven door de muziek, uitleeft in contrasten: scherp en vloeiend, exact en vrij, driftig en melancholiek. Maar hoe uiteenlopend ook, samen vormen de delen van de choreografie een even vanzelfsprekende als verbluffende eenheid, waarin zelfs de meest vertrouwde Van Manen-karakteristieken van een nieuwe gloed worden voorzien.

De choreografie begint met een krachtige openingsscène voor de vijf paren, gekleed in eenvoudige wijnrode en bronskleurige tricots. Vervolgens maken zich twee solistenkoppels uit het ensemble los. In de duetten van het eerste paar overheerst de ingehouden spanning – hoe vertraagd de bewegingen ook zijn die Van Manen op het Adagio en Chant creëerde, de dans is geladen met energie. De duetten van het tweede paar, gedanst op de Wiener Walzer en aan het slot van het ballet, zijn lichter van sfeer; tederheid en sensualiteit voeren hier de boventoon. Tussen de solistenduetten door stelen de beide mannelijke solisten de show met twee enerverende solo’s: de een vol trots en branie op de March, de ander wervelend als de razende woede in het Moto Perpetuo.

Van Manen is geen ‘winden-waaien-om- de-rotsen-choreograaf’, zoals hij dat zelf eens kernachtig formuleerde. Integendeel, hij streeft naar zo min mogelijk ballast om op die manier zo essentieel, zo controleerbaar mogelijk te zijn. Vandaar dat de structuur van zijn bewegingscomposities altijd helder en van een geraffineerde eenvoud is. Dit geldt zeker ook voor zijn Frank Bridge Variations, waarin hij vaak met simpele passen een maximum aan zeggingskracht weet te creëren. Tekenend hiervoor is de Funeral March, waarin het ensemble langzaam voortschrijdt over het toneel – een weergaloos effect waaruit een onbestemde dreiging spreekt, een gevoel dat nog wordt versterkt door de geraffineerde vormgeving van Keso Dekker en dito belichting door Bert Dalhuysen.

In de pers werd Van Manens Frank Bridge Variations ontvangen als een ‘voltreffer’. Een van de recensenten schreef: “Het ballet is fascinerend van begin tot einde (..) en zó muzikaal dat het lijkt of Van Manens gedanste antwoord op Benjamin Brittens negen miniaturen het enige juiste is.”

Tekst: Astrid van Leeuwen

‘A ballet about real people and actual feelings’

Juanjo Arqués on Full Frontal

Juanjo Arqués on Full Frontal: ‘A ballet about real people and actual feelings’

The new creation by the Spaniard Juanjo Arqués had to be postponed twice due to corona restrictions. The first wave of corona put paid to the plans, as did the Omicron variant last year. This meant that Arqués’ sources of inspiration and ideas for his new work changed as well. Now the premiere is imminent at last, he has chosen a theme that many of us have had to deal with both during and since the corona pandemic: the impact of stress on our daily lives.

Yes, he’s also stress-sensitive himself, admits the 46-year-old Juanjo Arqués. “As an artist, you automatically have to contend with tension and nerves. Especially as I’m someone who always takes risks. If I’m asked to choreograph a work within a few weeks, I’m quick to say yes, but then you’re usually stressed for weeks afterwards. On top of that, I have a mild form of ‘urban phobia’, so I don’t feel very comfortable in big crowds of people or on those ultra-long metro escalators.”

However, he says, his new piece Full Frontal is absolutely not an autobiographical work. “What concerns me is the role stress plays in our society and the effects it has on us.” Recently, he has been delving into the subject in detail – both into stress caused by external factors, such as noise, crowds, bad news and disasters, and into mental, inner stress. “Of course stress also has its positive sides. For instance, it can boost your immune system and help you defend yourself and others against threats or danger. But how do we deal with chronic stress? If you want to be a well-balanced person, then you need to keep such stress under control.”

URBAN ADAPTATION OF MICHAEL GORDON’S WEATHER ONE

In search of a piece of music for his new creation, Arqués came across Michael Gordon’s Weather One, which has agitated, strident sounds that for him clearly represent the urgency of stress and the associated fear and uncertainty. “It’s a composition that’s often been used by choreographers – including Itzik Galili in the Netherlands – so it’s really suited to dance. Only I won’t be using the piece in its most familiar version. Originally, Weather One was written for string orchestra, and Gordon later added sounds and effects that relate to nature. But for Full Frontal, with Gordon’s agreement, sound designer Ian Dearden is replacing these with sounds we associate mainly with life in a big city. After all, the sound of thunder doesn’t usually lead directly to stress, unless your house is struck by lightning, of course. So Ian will replace the thunder with the sound of an explosion or car crash, and the sounds of an Aeolian harp, for example, will become those of a church bell in his arrangement.”

WHEN THE AMYGDALA JUST KEEPS RACING ON

Arqués talked at length with dramaturge Fabienne Vegt, his regular set and costume designer Tatyana van Walsum and lighting designer Yaron Abulafia (for whom Full Frontal is the first collaboration with Arqués) on about how to transform his subject into a ballet. “We discussed the many external reasons for experiencing stress, from urban noise to aircraft flying overhead, and from bombardments to earthquakes. But also how stress can take over your state of mind, often subconsciously, when the part of your brain called the amygdala just keeps racing on and you can’t stop worrying – often about something totally insignificant.”

Arqués also spent a lot of time analysing Gordon’s composition. “The piece consists of diverse parts that are linked together, but like in many films there’s a sort of midpoint halfway through; the point at which the situation can’t actually get any worse, and from there it goes via other, smaller plot points towards a solution. That’s also the case in Gordon’s music. At the beginning, it’s very chaotic, then it builds up further and even further, and then suddenly there’s a sort of turning point.”

RAW MOVEMENT IDIOM

At the time of the interview, Arqués had only just had the first few exploratory rehearsals with his cast of dancers – five men and four women. With them, too, he will explore the phenomenon of stress and its effects in more depth, which he says will influence the choreography. “What I can say about it at the moment is that the movement idiom will be reasonably raw. My piece is about urgency, so not about decoration or perfection. I’ll be discussing themes like fear, worry, resistance and human resilience with the dancers. What do you do, for example, if you lose everything, after an earthquake like those in Turkey and Syria? How do we help each other in a situation like that, and how do you manage to get over it?”

In the ballet, the dancers will be wearing street clothing (designed by Van Walsum). “So that there’s less distance from the audience and it’s easier for people to identify with them”, says Arqués. Van Walsum’s designs also include two big screens. “I’m going to use them not just for people to appear from and disappear behind, but also to create shadows and suggest a multiplicity of the nine dancers – like a throng of people, as it were.” Abulafia’s lighting designs will also contribute to the meaning and the tension of the piece. “By using moving straight lines, I can create walls and define the space.”

NOT IMPOSING A STORY

The last thing Arqués wants is for his new creation to impose a story on his audience. “A journalist wrote about one of my earlier works that although it had a narrative feel to it, there was no narrative. Full Frontal will be like that as well. I don’t want to refer to one specific event or situation. My ballet is about the condition humaine. It reflects an aspect of our society and is about real people and actual events and feelings.”

He laughingly dismisses the question of whether some of the audience might not come away even more stressed than before. “That’s not my call. A ballet can be light, or it can be weightier. People’s preference is a personal choice. In recent years, I’ve often choreographed for operas, and most opera directors aren’t afraid of provoking people – quite rightly so. Moreover, as a spectator you’re anyway primarily a voyeur, an observer, so I don’t think you could get stressed from a twenty-minute ballet.”

Text: Astrid van Leeuwen

Music and dance in harmony

The music pieces in Four Temperaments

Music and dance in harmony: The music pieces in Four Temperaments

Since the fifteenth century, ballet music has grown from a simple accompaniment to complex compositions. The four ballets in Four Temperaments also attest to this evolution, whereby music and dance play equal roles.

The American-Russian choreographer George Balanchine (1904-1983) once spoke the famous and oft-repeated words: “See the music, hear the dance”. He thus expressed his vision of music as an essential part of the creation of a choreographic work. This view is also an extremely important aspect of the working process of the other three choreographers in the programme Four Temperaments: Hans van Manen, Ted Brandsen and Juanjo Arqués.

Harmonious character studies

The motto ‘See the music, hear the dance’ also formed the starting point for Balanchine’s groundbreaking The Four Temperaments. In 1940, he commissioned the German composer Paul Hindemith (1895-1963) to write around fifteen minutes of music – “something for piano that I can play at home”. However, Hindemith composed a piece lasting nearly thirty minutes, in which he explores the contrasting features and moods of the Ancient Greek temperaments at great length. The piece comprises five sections: one theme and four variations, whereby each variation corresponds to one temperament, in which Hindemith manipulates musical elements like time, rhythm and tempo to characterise the personality traits.

The first variation, associated with the melancholic temperament, opens with a dark rhythm that is reminiscent of a French Baroque overture. The dissonant piano is in stark contrast to the subdued, consonant violin. In the middle section of this piece, the strings and piano speed up and the tension increases, until it explodes in a slow, heavy march that is based on a sicilienne (originally an Italian folk dance that evolved into a music form). Hindemith uses alternating slow and quicker tempos, dissonance and a subtle interplay between strings and piano, in order to create a feeling of sadness and wistfulness. The melancholic variation is in complete contrast to the second, sanguinic variation, which opens with a cheerful, lively waltz with high-spirited melodies, and closes with a fiery statement, once again based on a sicilienne. The piece thus represents the lively, optimistic characteristics of a sanguine temperament.

The third, phlegmatic section starts off rather soporific and detached, although its measured tempo and calm rhythm also give a feeling of balance and stability. In direct opposition to this is the fourth and final variation. The choleric section begins with flaring passion, whereby the piano and strings vie to become the dominant part. The strings win in the middle section, but not without the piano questioning this conquest. The battle between the two instrument groups reflects the hot-headed character of a choleric temperament and is reinforced by the quick tempo and staccato playing.

Virtuoso variations

For Frank Bridge Variations, Hans van Manen also took inspiration from a composition of almost the same name: Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge by Benjamin Britten (1913-1976). In this ballet, Van Manen demonstrates his skill in creating strong contrasts – just like the ones heard between the different variations in the music.

From 1927, Britten had lessons in composition from the British composer Frank Bridge (1879-1941), and Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge is a musical tribute to his teacher. The theme Britten used as the basis for his variations comes from the second part of Bridge’s Three Idylls for String Quartet, which also explains the title of Britten’s composition. The introduction immediately demands the listener’s attention and briefly acquaints us with this ‘Theme of Frank Bridge’. It soon resolves into the Adagio, the first variation. The Adagio slows down the original theme, allowing the rich timbres of the string orchestra to be heard to the full. The development from the lively March in the second variation, via the dreamy, tender Romance, to the wild musical phrases in the following sections shows how Britten succeeds in composing a wonderful drama of musical contrasts from one single theme.

Compelling foxtrot

For the quadruple bill Four Temperaments, artistic director Ted Brandsen created a new ballet to the swinging piece of music The Chairman Dances by the American composer John Adams, which he originally wrote for his opera Nixon in China. The composition The Chairman Dances is lively and jazzy, reflecting the foxtrot dance style that gives the work its subtitle: ‘Foxtrot for Orchestra’. The piece has a mix of driving rhythms and a colourful orchestration, in which Adams’ characteristic minimalist style flourishes.

The piece opens with the rich, deep and warm timbres of the bassoons and violas playing the main theme, following which more instruments are gradually added to create a pulsating structure. The full orchestra then plays different rhythms, building up a busy sound that finally ebbs away again, so that only the piano and percussion instruments remain to play the chord scheme of the major theme. The composition alternates between 2/2 and 3/2 time, thus maintaining a steady, strong beat. This creates a tension that is kept up by the composition for the whole thirteen minutes. The Chairman Dances closes with a remarkable ending that symbolises a gramophone winding down: a nod to the third act of Nixon in China.

Turbulent soundscapes

For his new work Full Frontal, the young choreographer Juanjo Arqués used music by the contemporary composer Michael Gordon. Weather One, orchestrated for string sextet, breaks through the boundaries of both classical music and pop music. Gordon’s minimalist style is somewhat reminiscent of John Adams, but his compositions are not nearly as complex. He transforms subtle rhythms into incredibly powerful music that suggests a mix of punk rock, jazz and classical modernism.

Gordon’s conflicting, simultaneous rhythms create forceful, energetic music. His Weather One – the first section of the four-part work Weather – is inspired by chaotic weather patterns. The way in which Gordon has written the parts for the strings creates a hypnotic and meditative listening experience. Strongly inspired by Vivaldi’s motoric way of composing for strings, Gordon has written a work that is continually in motion and driving forwards.

Each composition in Four Temperaments represents a multi-layered work to which the dance does full justice. From classical masterpieces to innovative contemporary works, the four composers have succeeded in inspiring choreographers to enter into the dialogue between music and dance.

Text: Stan Schreurs

programmaboek

BECOME A FRIEND OF DUTCH NATIONAL BALLET

As a Friend you support the dancers and makers of Dutch National Ballet. You are indispensable to them and we are happy to do something in return. For Ballet Friends we organize exclusive activities behind the scenes. You will receive the Friends magazine from us and you will receive priority when ordering tickets.