Raymonda

Content

- Preface

- Credits

- Cast sheet

- Synopsis

- History of Raymonda

- Interview with Rachel Beaujean (with contributions from Grigori Tchitcherine)

- The music for Raymonda

- Jérôme Kaplan about the set and costumes for Raymonda

- Youval Kuipers about the fight choreography for Raymonda

- Biographies artistic team

- Biographies soloists

- Biographies character dancers

Preface by Ted Brandsen

Voorwoord door Ted Brandsen

Breathtaking splendour with new fervour

Like a reincarnation! That’s how you could describe the world premiere of our new Raymonda production in April 2022. Following an extremely difficult corona period for the dancers – in which they could originally only work in the confines of their living rooms on keeping their technique up to scratch – they gave their all, under the guidance of associate artistic director Rachel Beaujean, in order to make a success of the production. And they exceeded their goal by far! In its first series of performances, Raymonda was always received with standing ovations, got four- and five-star reviews in the Dutch and international press, and was proclaimed ‘Production of the Year’ by the leading British magazine Dance Europe.

It is therefore with a great sense of pride that we now present our second series of performances of Raymonda, through which we’re sure to also reach many people who couldn’t get a ticket for the first series. I’m particularly proud of Rachel, who did years of research into this world-famous ballet, which had never been performed in full in the Netherlands before, and created her own interpretation of Marius Petipa’s last masterpiece on the basis of that research. In doing so, she succeeded in adding new fervour to the breathtaking splendour of this large-scale classical fairy-tale ballet, whilst also giving a new interpretation of the story, which is suitable for and relevant to the times we live in today.

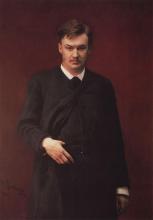

The fact that Raymonda still attracts such admiration 125 years after its original staging is due not only to Petipa’s choreographic masterpiece – in which he combined all the knowledge and expertise from his entire career – but also to the impassioned music of Alexander Glazunov. And especially for our production, the Frenchman Jérôme Kaplan has designed wonderfully refined, yet also extremely fresh and timeless scenery and costumes, inspired by the different countries and spheres in which Raymonda takes place, in the Middle Ages.

For our dancers, Raymonda provides plenty of opportunity to prove themselves in challenging solos, spectacular variations and colourful character dances. In addition, this glittering and moving fairy-tale spectacle – complete with happy ending – creates a positive counterbalance, for them and for you, at a time when we’re surrounded by so many conflicts and wars. In the fervent hope that 2024 will bring us more peace and tolerance, I wish you a pleasant and loving Christmas and New Year and, for now, a festive and magical evening.

Ted Brandsen

Director Dutch National Ballet

Credits

Credits

Credits

Choreography

Marius Petipa

Production and additional choreography

Rachel Beaujean

Music

Aleksandr Glazoenov – Raymonda, opus 57 (1898)

Set and costume design

Jérôme Kaplan

Lighting design

James F. Ingalls

Assistant research, production and staging Mazurka, Pas Hongrois and Romanesca

Grigori Tchitcherine

Choreography warriors and sabre dance

Ted Brandsen

Fight choreography

Youval Kuipers

Music preparation and supervision

Boris Gruzin

Musical advice

Matthew Rowe

Olga Khoziainova

Score and arrangement

Lars Payne

Dramaturgical advice

Janine Brogt

Staging Pas Classique Hongrois

Guillaume Graffin

Larissa Lezhnina

Ballet masters

Guillaume Graffin

Michele Jimenez

Sandrine Leroy

Larissa Lezhnina

Judy Maelor Thomas

Jozef Varga

Musical accompaniment

Dutch Ballet Orchestra conducted by Vello Pähn

With cooperation of

The students and pupils of the Dutch National Ballet Academy (Amsterdam University of the Arts)

Staging students of the Dutch National Ballet Academy

Dario Elia

World premiere

7 January 1898, Mariinsky Theatre, Saint Petersburg

World premiere production Rachel Beaujean at Dutch National Ballet

3 April 2022, Dutch National Opera & Ballet, Amsterdam

Sets, props, wigs and makeup, and lighting

Technical department of Dutch National Opera & Ballet

Production manager

Anu Viheriäranta

Stage managers

Wolfgang Tietze

Pieter Heebink

Production supervisor

Sieger Kotterer

First carpenter

Jop van den Berg

Lighting managers

Wijnand van der Horst

Lighting supervisor

Angela Leuthold

Michel van Reijn

Sound engineer

Raymond Roggekamp

Follow spotters

Lee Hayes

Hein Hazenberg

Famke van der Marel

Panos Mitsopoulos

Laura Nagtegaal

Anton Shirkin

Marleen van Veen

Follow spotters coordinator

Ariane Kamminga

Props

Jurgen van Tiggelen

Costume production

Costume department Dutch National Opera & Ballet, in collaboration with: Das Gewand, Ina Kromphardt Kostüm & Schnitt, Martine Douma, Jeanine Pieterse, Hermien Hollander, Renske Kraakman, Lisa Kaimer, Saskia Stöckler, Esther Datema, Herma Stal, Fred van Gestel, Anita van Dinther, Merel Kaspers

Assistant costume production

Eddie Grundy

First dresser

Andrei Brejs

First make-up artist

Frauke Bockhorn

Introductions

Lin van Ellinckhuijsen

Swantje Schäuble

Hanke Sjamsoedin

Duration

two hours and fifty minutes, including two intervals

Dutch Ballet Orchestra

First violin

Sarah Oates, concertmeester

Cordelia Paw

Kotaro Ishikawa

Suzanne Huynen

Robert Cekov

Jan Eelco Prins

Tinta Schmidt von Altenstadt

Majda Varga-Beijer

Bert van den Hoek

Tineke de Jong

Marijke van Kooten

Marina Meerson

Lena ter Schegget

Inger van Vliet

Myrte van Westerop

Second violin

Radka Dijkstra-Dohnalová

Olga Caceanova

Willy Ebbens

Christiane Belt

Michiel Commandeur

Casper Donker

Sandra van Eggelen-Karres

Saskia Frijns

Anita Jongerman

Leonie Kleiss

Irene Nas

Francesco Vulcano

Viola

Naomi Peters

Arwen Salama-van der Burg

Maria Ferschtman

Joël Waterman

Örzse Adam

Eduard Ataev

Bas Egberts

Wouter Huizinga

Ingerid Waleson

Karen de Wit

Cello

Artur Trajko

Lies Schrier

Evelien Prakke

Willemiek Tavenier

Emma Besselaar

Csaba Erdös

Wijnand Hulst

Oliver Parr

Xandra Rotteveel

Double bass

Jean-Paul Everts

Annelies Hemmes

Lucía Mateo Calvo

Florian Lansink

Louis van der Mespel

Jurjen de Roest

Flute

Sarah Ouakrat

Karin Leutscher

Marie-Cécile de Wit

Oboe

Juan Esteban Mendoza Bisogni

Arthur Klaassens

Clarinet

Ina Hesse

Abraham Gomez Chapa

Joris Wiener

Bassoon

Janet Morgan

Maud van Daal

Horn

Ward Assmann

Lies Molenaar

Christiaan Beumer

Hendrik Marinus

Trumpet

David Pérez Sánchez

Erik Torrenga

Andreas Oosterkamp

Trombone

Bram Peeters

Wilco Kamminga

Marijn Migchielsen

Tuba

Ries Schellekens

Timpani

Peter de Vries

Percussion

Richard Jansen

Michiel Mollen

René Oussoren

Arjan Roos

Harp

Kerstin Scholten

Jet Sprenkels

Piano

Daan Kortekaas

Banda:

Trumpet

Hans van Loenen

Bas Otten

Alejandro Zamorano Fernández

Euphonium

Dominique Capello

Rickwin Poelma

Gerd Wensink

Synopsis

Synopsis

Synopsis

Act 1

Scene one - birthday party

Raymonda is the great-niece of Countess Sybille de Doris, who raised her at her home in Provence. Her grandfather, the Hungarian Grand Duke Sandor of Belovár, sent Raymonda to his sister Sybille, following the loss of both her parents. Raymonda has grown up in the warm, relaxed atmosphere of the court, where she has always been surrounded by love. She went on adventures with her friends in the charming landscape of Provence and occupied herself with music, dance and poetry. Now she stands on the threshold of adulthood. She cherishes a great affection for the young, brave knight Jean de Brienne.

On her birthday, Raymonda’s friends are busy preparing for the party. The atmosphere is cheerful and expectant. Jean arrives and greets Countess Sybille. Raymonda’s best friends Henriette and Clémence enter as well, along with their boyfriends Bernard and Béranger. The castle fills with people and children from the neighbourhood. Everyone is waiting for Raymonda to arrive, and the children scatter flowers to welcome her.

A radiant Raymonda appears, delighted that so many guests have come to her party. Jean de Brienne’s presence lends her wings. Together, they thoroughly enjoy the party, until the arrival of two young knights who are friends of Jean. They invite him to a big tournament taking place elsewhere and ask him to leave with them immediately. Raymonda doesn’t want him to go, but Jean can’t resist the temptation. The prospect of fighting and the glory he could achieve are more important to him than Raymonda’s disappointment. He gives her a beautiful scarf as a token of his love, but for Raymonda the gift can’t make up for his unexpected departure. Jean takes his leave nonetheless.

The arrival of Raymonda’s grandfather, Grand Duke Sandor, creates a diversion. After a happy reunion with his sister and granddaughter, he requests everyone’s attention. He says he has chosen Raymonda to succeed him as grand duchess, and hands her the insignia of her new title. He announces that another party will be held in a few days time, to celebrate Raymonda’s inauguration. The arrival of another guest is announced unexpectedly at the eleventh hour. It is the celebrated, warlike and art-loving sheikh of Córdoba, Abd al-Rahman. He was not aware of the birthday party, but is welcomed to the court nevertheless as an old acquaintance of the grand duke. He is immediately invited to attend the festivities for Raymonda’s inauguration and accepts the invitation. He is impressed by Raymonda, kissing her hand politely and elegantly. His attentions confuse her. Although she is fascinated by this stranger, she doesn’t understand the strong feelings that he suddenly arouses in her. What is happening to her?

The guests take their leave and Raymonda remains behind with her best friends to calmly reflect on all the events of the party. Raymonda is not exactly sure of her feelings. So much has happened during the day and she has conflicting emotions. Henriette and Clémence dance an old court dance with Bernard and Béranger. The simple, emotive melody reminds Raymonda of a lullaby. She plays pensively with the scarf Jean gave her and begins to dance with it. The soft music of the lute creates a dreamy atmosphere. As Raymonda says goodnight to her friends, reality seems far away. She wants to sleep, but in the half-light between waking and sleeping, she is overwhelmed by an intense sensation

Scene two - dream

Raymonda sees before her Jean de Brienne, who has embodied her ideal of a man since she was a young girl. But despite her desire, he remains at a distance, surrounded by a group of girls who all remind her of herself. Finally, Jean breaks free of the circle of girls and approaches her. At last, Raymonda can bask in Jean’s loving attention once again. All is well between them now and their confusion and estrangement seem to have been just a figment of their imagination. But this doesn’t last for long. Once again, Jean disappears in the night-time mist, surrounded by the girls who are Raymonda’s alter egos. When she tries to reach him again, she feels only thin air.

Then she suddenly sees Abd al-Rahman in front of her instead of Jean. His overwhelming male personality fascinates Raymonda once again and she is utterly confused. She feels his presence as a threat, yet cannot escape the magnetism of this man, who is so different to Jean de Brienne in every respect. Abd al-Rahman declares his love, and Raymonda is swept up by his emotions. Then the vision vanishes as suddenly as it appeared. As Raymonda wakes up, the dream loses none of its power. She realises that something has happened to her that is unfathomable. Are these feelings real, or no more than an illusion? Can she ever return to being the girl she was yesterday? And does she want that? Or does a whole new life await her?

Act 2

Inauguration

In a walled garden, the guests gather for the inauguration of Raymonda as the Grand Duchess of Belovár. Contrary to expectation, Jean de Brienne has not yet returned from the tournament. All the guests arrive and are welcomed by Countess Sybille, Grand Duke Sandor and Raymonda’s friends.

Soon after Raymonda appears with her friends to greet all the guests, Abd al-Rahman makes an impressive entrance, accompanied by a large retinue. He greets the grand duke and Countess Sybille, and declares his love for Raymonda in no uncertain terms. Now that her dream has suddenly become reality, in the light of day, Raymonda feels her resistance and doubts melt away. Abd al-Rahman moves her to the depths of her soul. How could she deny these feelings? Her family and friends don’t know quite what to make of this sudden change in Raymonda, and decide to postpone their reaction for the moment.

The festivities get underway and Abd al-Rahman’s male retinue performs an exciting sword dance. It is followed by a Spanish dance that is possibly even more compelling, in which Abd al-Rahman takes part himself. Then he invites Raymonda to dance to the Arabic music of his retinue. Raymonda’s friends and family look on in concern, as she improvises and enchants Abd al-Rahman with her dancing. The couple’s utter devotion to one another is clearer than words could express. The tension is defused by a wild dancing spree in which everyone takes part, and the guests from Provence, Hungary, Spain and Arabia mingle freely.

Jean de Brienne returns as the proud victor of the tournament. When he sees Abd al-Rahman at Raymonda’s side, he realises something unexpected is going on. Raymonda approaches him and tries to explain what happened to her while he was away, but Jean doesn’t want to listen. He is furious and turns on Abd al-Rahman. The latter doesn’t want to fight, but has to defend himself. Raymonda steps cool-headedly between the two men, begging them not to fight. But Jean can’t stop himself and when Abd al-Rahman is distracted for a moment, he wounds him with his sword. Abd al-Rahman falls and Raymonda rushes to his side. Kneeling by him, she only draws breath again when she sees that the wound is not fatal. Jean’s flagrant breach of his chivalrous code bewilders her. Looking at him, it’s as if she sees a stranger. Her expression tells Jean that he has lost her for good. Their youthful love is over. All that Jean can do is accept this new reality and leave with his companions. The court and all the guests gradually recover from the shock. Grand Duke Sandor and Countess Sybille give Raymonda and Abd al-Rahman their blessing.

Act 3

The wedding

The wedding of Raymonda and Abd al-Rahman is celebrated at the court of Belovár, with a big divertissement of Hungarian dances in their honour.

Controversial libretto and masterly choreography and music

History of Raymonda

Controversial libretto and masterly choreography and music

Raymonda was the last great masterpiece by Marius Petipa, the choreographer whose oeuvre influenced our idea of classical ballet once and for all. After its premiere in St Petersburg in 1898, Raymonda has always remained successful in Russia, but its weak yet controversial storyline meant that the complete ballet was hardly even performed in the West. In recent times, however, a Raymonda revival seems to be underway, as other companies besides Dutch National Ballet are also presenting their own interpretation of Petipa’s glittering jewel of a ballet.

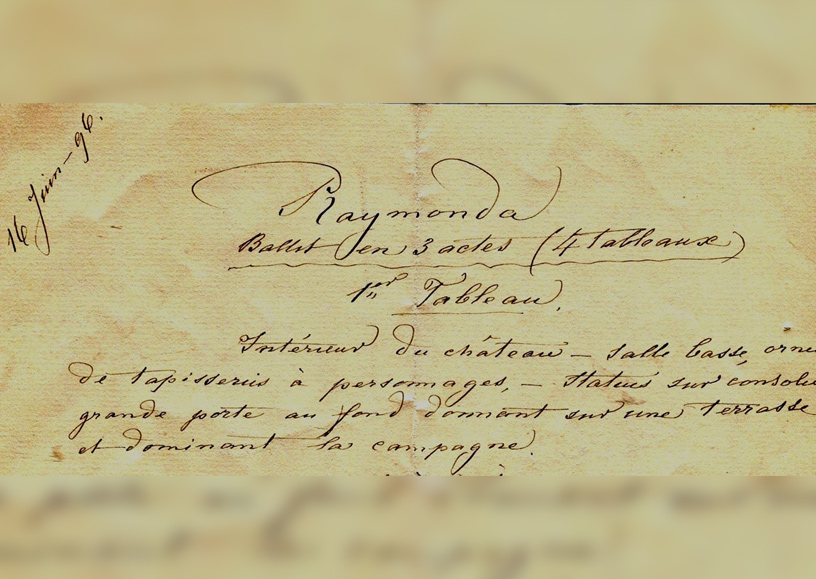

“Dear Mr Petipa, Attached to this is Mme. Pashkova’s manuscript. You could do something with it. There is little dance; on the other hand, there is too much pantomime. When you have a moment of time, you will tell me what to do. Your very devoted Vsevolozhsky.”

In 1895, along with this short, unenthusiastic note, Ivan Alexandrovich Vsevolozhsky, the director of the Imperial Theatres in St Petersburg, sent Marius Petipa a version he had already adapted himself of the libretto of Raymonda written by Lydia Pashkova. At the time, Petipa had already been a choreographer with the Imperial Ballet for 33 years – and principal choreographer from 1871 – and during that time he had created one ballet spectacle after another for the company.

Pashkova had been pestering Vsevolozhsky with letters since 1889, in which she offered him scenarios for ballets, such as The Beauty from Canton, Cinderella (performed in the Mariinsky Theatre in 1893), Melusina and the erotic, if not banal Halim, the Bandit of Crimea, which Petipa managed to avert from the Mariinsky stage with some difficulty. Both Petipa and Vsevolozhsky knew – as shown by Vsevolozhsky’s note – probably all too well that Pashkova was no gifted librettist, but rather a mediocre writer who regularly visited far-flung places and was mainly interested in fashion, ballrooms, high-society marriages and divorces, and other gossip and scandals. However, Vsevolozhsky could not avoid her, as after her first marriage to the Russian poet and author Nikolai Teleshov, Pashkova married Hippolite Pashkov, a journalist who held a high position at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and was close to the Russian court, which funded the Imperial Theatres.

Superficial nonsense

So Petipa was none too happy with the libretto for Raymonda. It was a rather superficial, simplistic – and according to some even ridiculous – story about the white Christian crusader Jean de Brienne, who rescues Raymonda, a noble beauty, from the hands of the villainous Saracen (North-African Arab) and Muslim ruler Abderakhman. Pashkova had impressed upon him that the story was based on a mediaeval legend, but although a knight named Jean de Brienne appears to have existed, the legend has never been found. She also feigned a sincere historical interest, but Pashkova seems mainly to have sought an excuse for writing an ‘exotic’ story. She cleverly latched on to the renewed interest at the time in the Middle Ages and the ‘holy’ crusades, as well as the prevailing fascination with orientalism.

So Petipa took the liberty of making adjustments to the original libretto, which was later described as ‘very weak and geographically confusing’, by Petipa biographer Nadine Meisner, and was even dismissed as ‘nonsense’ by Petipa’s choreographic heir George Balanchine. On 18 June 1896, Petipa wrote to Vsevolozhsky, “I have taken the liberty of changing the plot of the ballet somewhat, and it is therefore absolutely necessary that in August I receive the valuable advice of Your Excellency, who has already revised the script by Lydia Pashkova.”

More passion

In close cooperation with Alexander Glazunov – the young composer engaged for Raymonda by Vsevolozhsky– Petipa put more passion into the libretto, focusing mainly on Raymonda’s development and her despair in love. This placed more emphasis on the lyrical aspects, as in a symphonic ballet, rather than on the actual, rather flimsy storyline. The fact that he had thus not taken Pashkova seriously enough, in her eyes, was to cost Petipa dearly. The title page of the score of Raymonda, which was published before the premiere, stated: ‘The scenario by Lydia Pashkova and Marius Petipa’. But all the subsequent publications stated: ‘Ballet in three acts – a work by Mme. L. Pashkova’. In other words, she was specified as the author of the ballet, while Petipa was only named as responsible for the ’dancing and staging’.

Learning about freedom while chained

Just as he had done previously with Tchaikovsky, for The Sleeping Beauty, The Nutcracker and Swan Lake, Petipa provided Glazunov with detailed instructions for the storyline, length, time signatures and tempos of the various music sections. The collaboration between the 79-year-old, long-celebrated choreographer and the 30-year-old composer, who was writing his first ballet, had its ups and downs, as shown by a letter from Petipa to a friend: “Mr Glazunov does not want to alter a single note in the variation of Mlle. Legnani (the original Raymonda – ed.), and neither will he make a small cut in the galop. It is terrible to compose the ballet with a composer who has already had the music printed and sold it to the publisher.”

Glazunov wrote later in his biography, when he had gained fame as a composer, “The necessity of taking account of the requirements of the choreography restricted me … but it also toughened me up in dealing with symphonic problems. I had to fulfil the choreographer’s wishes and sometimes go no further than phrases of sixteen or thirty-two bars, but even despite these iron fetters, the best school for developing and fostering a sense of musical form was not disrupted. Isn’t being chained the best way to learn about freedom?”

The fact that Glazunov nevertheless held Petipa in high esteem was revealed in 1907, at a concert on the occasion of his silver jubilee, when he profusely thanked the old master, who was present at the concert, for their collaboration, on which the audience gave Petipa a standing ovation. It was an unprecedented – and for the management of the Imperial Theatres at the time probably extremely unwelcome – accolade for the master choreographer, who had left two years earlier due to opposition and harassment.

Last spectacle ballet

Whatever the case, the pair succeeded in making an absolute masterpiece of Raymonda, whereby Pashkova’s superficial scenario turned out to be no more than a vehicle for Petipa’s brilliant choreography and Glazunov’s beautiful music. The premiere of Raymonda took place on 7 January 1898, at the Mariinsky Theatre in St Petersburg. After the three Tchaikovsky ballets, it was the last large-scale and extremely successful ballet spectacle created by Petipa in the closing decade of the nineteenth century.

“Petipa’s creativity, great artistic taste and mastery were revealed in their full beauty and power in Raymonda. The ballet master carefully avoided any stunt used purely for effect – everything about Raymonda is artistic, intelligent and fine. For this reason, the production was a glorious success, such as not seen on the ballet stage for a long time (..) the audience unanimously expressed their delight and amazement at Petipa’s phenomenal artistic creativity”, wrote the Russian music magazine Theatre Echo the day after the premiere.

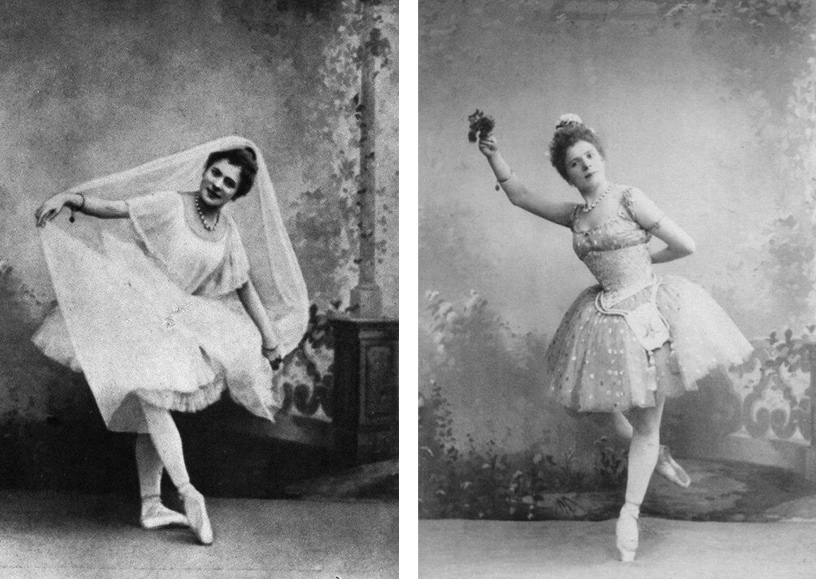

Technical wonder

Apart from the choreography and the music, the Italian ballerina Pierina Legnani, who danced the role of Raymonda, also received great praise. Legnani, one of Petipa’s favourites and generally regarded as one of the greatest ballerinas of her generation, enchanted the premiere audience with her variations and the pas de deux. For nineteenth-century standards, she was a true technical wonder. “Despite the extreme difficulty of her role (she appeared in all four acts), Mademoiselle Legnani danced exquisitely – with incomparable grace, plasticity and powerful movement”, wrote a dance critic from Theatre and Music.

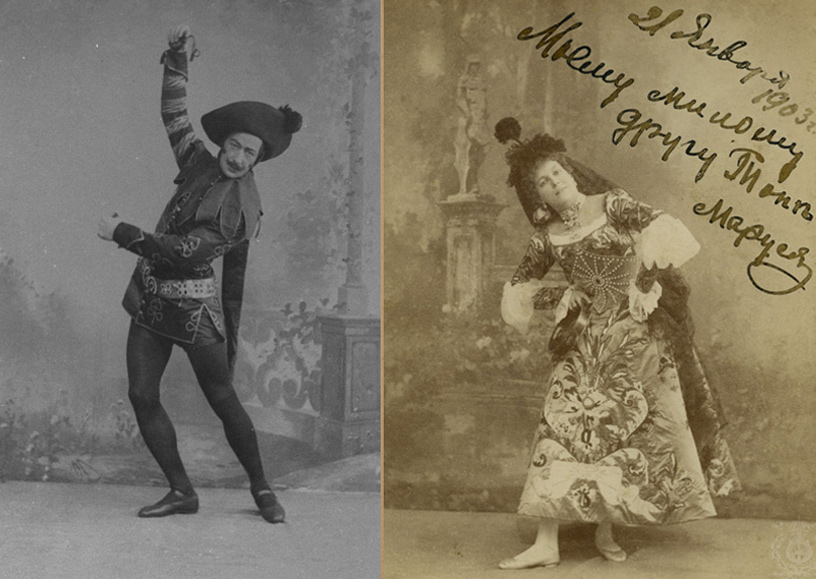

The young Russian dancer Sergei Legat, who was just 22 at the time, danced the role of Jean de Brienne, while his 54-year-old compatriot – and former teacher – Pavel Gerdt played Abderakhman. Olga Preobrazhenskaya and Claudia Kulichevskaya danced the roles of Raymonda’s friends Henriette and Clémence at the premiere. Petipa created the most wonderful virtuoso solos for the three women, comparable to those of Princess Aurora and the fairies in his Sleeping Beauty. The two productions had other things in common as well, including a dreamlike vision scene, a ‘cour d’amour’ to celebrate the return of the male protagonist and an exuberant wedding act as a finale.

From St Petersburg to Moscow

Due to the ballet’s great success, Raymonda soon became one of the standard works in the Russian ballet repertoire. In St Petersburg, Petipa’s original version remained practically unchanged for thirty years, despite new stagings by Fedor Lopukhov (1922) and Agrippina Vaganova (1933). That was until Vasily Vainonen created a new production in 1938, with an adapted libretto by himself and Yuri Slonimsky. For the first time, Abderakhman was not the bad guy, and Raymonda eventually chose him (in subsequent versions, this was changed back again).

Raymonda was introduced to Moscow as early as 1900. Initially, the ballet was taught to the Bolshoi Ballet, in strict accordance with Petipa’s instructions, by Alexander Gorsky – who had performed as a cavalier and in the Saracen dance at the world premiere in 1898. Eight years later, however, Gorsky created his own version of the ballet, which deviated considerably from Petipa’s original. Fortunately, the greatest choreographic gems (including the Grand Pas Classique Hongrois in the third act) were preserved, sometimes against Gorsky’s will. For instance, the Bolshoi ballerina Ekaterina Geltser (who had danced the role of Raymonda back in Petipa’s time in St Petersburg) strongly opposed Gorsky’s adaptations, so he had to tolerate her performing all her solo variations unchanged.

It is generally accepted that Gorsky’s version was more lively and probably more dynamic, but at the same time more eclectic and less refined than Petipa’s original. In any case, Gorsky’s production soon came under attack. Supporters of classicism found his changes unacceptable, while avant-gardists accused him of making concessions and half-hearted decisions. Yet Gorsky’s version survived for over thirty years, and although many of his adaptations were later changed back again, Gorsky’s influence can still be seen in the Bolshoi productions by Leonid Lavrovsky (1945 and 1960) and Yuri Grigorovich (1984 and 2003).

From Sergeyev to Nureyev

Around 1903, the choreography for Raymonda was written down by Nicolai Sergeyev and others, using the method of Vladimir Stepanov, a former dancer with the Imperial Ballet and one of the first people to embark on dance notation. This and other notated Petipa masterpieces is currently kept in the archives of Harvard University, in America, but as the Raymonda notation consists mainly of minimal lines and arrows, and is thus barely ‘legible’ to anybody nowadays, it is not easy to ascertain which parts of the ballet are original and which are not.

One of the most important versions that still exists – believed by experts to be the closest to Petipa’s choreography – is in any case the one by Konstantin Sergeyev, which was created for the Mariinsky Ballet in 1948 and is still performed by the company today. It is certain that Sergeyev also added his own sections, which were created ‘in the spirit of Petipa’, but nevertheless his version has formed the definitive inspiration for many later versions of Raymonda.

For example, the legendary dancer Rudolf Nureyev, who deserted to the West in 1961, took his notes of Konstantin Sergeyev’s production as his basis, when he taught a complete version of the ballet to The Royal Ballet, to be performed at the Spoleto Festival in Italy. The company later went on to perform only the third act of the ballet. Nureyev then staged Raymonda for Australian Ballet, Zürich Ballett and American Ballet Theatre. But it was the version he created in 1983 for Ballet de l’Opéra national de Paris – where he had just been appointed artistic director – that became the best-known, and it is thus often regarded in Europe as the most important full-length production of Raymonda to date and the first to be created completely outside Russia.

Raymonda in the West

Up to then, it had long been the case that most performances in the West were only of parts of Raymonda. As early as 1909, Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes danced the czardas and the Grand Pas Classique Hongrois from the ballet, in Paris, as part of Michel Fokine’s arrangement for the gala performance Le Festin. And in 1915, the ballerina Anna Pavlova presented a two-act version, entitled Raymonda’s Dream, in New York, choreographed by Ivan Clustine. George Balanchine and Alexandra Danilova – who had both danced with the Mariinsky Ballet (formerly the Imperial Ballet) – staged an abridged version of Raymonda in 1946 for the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, for which Alexandre Benois designed wonderful sets and costumes. For his New York City Ballet, Balanchine went on to create three of his own Raymonda pieces, to music by Glazunov: Raymonda Pas de Dix (1955), Raymonda Variations (1961) and Cortège Hongrois (1973). The first, Raymonda Pas de Dix, was also the first ‘Raymonda work’ to enter the repertoire of Dutch National Ballet, in 1964. It was only much later, in 2005, that Dutch National Ballet presented a pas de deux from Petipa’s ballet, and in 2014 the company danced the Grand Pas Classique Hongrois from the ballet for the first time.

In recent years, however, an international revival of Raymonda seems to be underway, and the great significance and stunning beauty of the masterpiece by Petipa and Glazunov has been underlined by various new, full-length productions. Some choreographers have chosen to remain close to the traditional choreography and storyline, such as Sergei Vikharev, who made a partial reconstruction of Raymonda from the original notation for Balletto del Teatro alla Scala, in Milan, in 2011. That choice was also made, for example, by Annemarie Holmes and Kevin McKenzie for their production for the National Ballet of Finland (2003) and American Ballet Theatre (2004), and by Ray Barra in his version for Bayerisches Staatsballett, in Munich, in 2001.

Others, however, have decided to give their own personal twist to the ballet, whereby most have also chosen to steer clear of the controversial, discriminating implications in the original libretto (where the Western Christian is the hero and the Saracen Muslim the villain). For instance, in his version for Australian Ballet (2006), the Australian choreographer Stephen Baynes linked the story of Raymonda to the marriage between Hollywood star Grace Kelly and Prince Reinier of Monaco. And in his production for the Royal Swedish Ballet (2014), the Swedish choreographer Pontus Lindberg links the world premiere of Raymonda in 1898 to the opening of the Opera House in Stockholm in the same year. He presents the ballet as a rehearsal at the new theatre at the time, whereby a ménage à trois arises between the principal couple and a young male dancer.

The Best of Petipa

In 2022, no fewer than two exciting new productions of Raymonda saw the light of day. In her last year as artistic director of English National Ballet, the Spaniard Tamara Rojo presented a distinctive version of the ballet in London. Raymonda takes the guise of a sort of Florence Nightingale, a nurse who gets engaged to a British soldier during the Crimean War, but soon afterwards develops feelings for his ally Abdur, a leader in the Ottoman army.

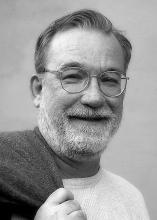

A few months later, the world premiere of the first Dutch production of Raymonda took place in Amsterdam. Following successful interpretations of classics like Giselle, Paquita and Les Sylphides, associate artistic director Rachel Beaujean created her own version of Marius Petipa’s last great masterpiece. Respect for tradition took priority, because, says Beaujean, “In Raymonda, you see choreographic ideas from earlier famous ballets like Swan Lake and The Sleeping Beauty, but then in the most refined and purest form imaginable. You could easily call it ‘The Best of Petipa’.” At the same time, Beaujean and her team deliberately did not want to close their eyes to the stereotypical, discriminating way in which Petipa’s Raymonda polarises the courtly, elegant West and the barbaric, unrestrained East. So in her version, Beaujean unites these two world in a new dramaturgy, focusing on rapprochement rather than dichotomy.

Text: Astrid van Leeuwen

With thanks to Grigori Tchitcherine and Peter Koppers

‘An incredibly beautiful ballet’

Interview with Rachel Beaujean (with contributions from Grigori Tchitcherine)

‘An incredibly beautiful ballet’

Over the years, Dutch National Ballet has presented its own distinctive interpretations of nearly all the big ballet classics. But one production was still missing: Raymonda, the last great masterpiece by the French-Russian choreographer Marius Petipa. So in 2022, associate artistic director Rachel Beaujean decided to create her own version of this ballet, but not without giving a big twist to the story. She says, “Petipa’s choreography for Raymonda is simply too beautiful to remain unseen, but for these gems you have to think up a crown and setting that fit the times we’re living in today.”

No, she never saw Raymonda as a child or young ballet student. “Simply because the ballet wasn’t performed in the West when I was young. It was Rudolf Nureyev who brought the production to the West, long after its premiere in St Petersburg in 1898. In 1964, he created his first version of Petipa’s masterpiece for The Royal Ballet, in Britain, but soon afterwards it was only the third act that was performed. However, the version he made in 1983 for Paris Opera – shortly after being appointed artistic director there – did hold firm, and it’s still danced today.”

So Rachel Beaujean initially got to know Raymonda through video and film. “Apart from Nureyev’s version, it was mainly a film of the Mariinsky Ballet from 1980, with Irina Kolpakova as Raymonda, which made a deep impression on me. This Mariinsky version was created in 1948 by Konstantin Sergeyev, who appeared himself in one of the early adaptations of Petipa’s ballet, so it was close to the source.”

Precisely the fact that Raymonda was Petipa’s last big hit production – following ballets like The Sleeping Beauty, The Nutcracker and Swan Lake – is what makes the ballet so rich and special, says Beaujean. “In Raymonda, he was able to incorporate and perfect everything he’d done before, in the way of solo variations, pas de deux and other choreographic elements. From the vision variations to the Pas d’Action: they’re all incredibly beautiful. I thought”, says Beaujean passionately, “it was inconceivable that Dutch audiences would never get to see all this beauty.”

Preparations for the first production of Raymonda to be made in the Netherlands started already in 2018, four years before the premiere of the ballet. “Ted Brandsen and I began by familiarising ourselves with the existing interpretations.” For instance, they watched the version made by Ray Barra in 2001 for the Bayerisches Staatsballett, in Munich, which follows the original libretto by Lydia Pashkova. “Ted and I soon realised we didn’t want to do that. In our view, the nineteenth-century story has clear elements of white supremacy, and we didn’t want to close our eyes to that fact at Dutch National Ballet. Petipa’s choreography for Raymonda contains many absolute gems, but Ted and I believed that you have to think up a crown and setting for those gems that fit the times we’re living in today.”

So whereas in the original libretto, Raymonda puts up no resistance to her predestined marriage to the white crusader Jean de Brienne, in Beaujean’s version she is a young woman who makes her own decisions. “In the original story, she’s in danger of being abducted by the Muslim Abd al-Rahman, who’s enchanted by her beauty. Although Raymonda develops feelings for him, eventually she marries De Brienne anyway, who rescues her from the clutches of Abd al-Rahman. In our version, it’s clear from the start that there’s an attraction between Raymonda and Abd al-Rahman, and that she makes a deliberate choice for true love.”

À la Bridgerton

Beaujean compares her intervention in the story to the choices made by the makers of the popular Netflix series Bridgerton. In this costume drama about British high society during the Regency period – at the beginning of the nineteenth century – the characters are played by a mixed cast of white and black actors, which is surprising, as it does not reflect the reality of the period. Beaujean says, “Just like in Bridgerton – even though Raymonda takes place in the Middle Ages – we, too, want to sketch a world where women do make their own decisions and where people from different cultures do get married to one another.” She laughs, “What’s more, in the production we saw in Munich I immediately found Abd al-Rahman much more fun, colourful and sexy than Jean de Brienne. So I simply didn’t think it was logical that she would marry a person who turns out in the story to be so vain and really rather dull.”

Original notation

Following previous successful interpretations of classics like Giselle, Paquita and Les Sylphides, Beaujean worked for over four years on her research into the history of Raymonda and on the creation of her new version of the ballet. She was assisted not just by Ted Brandsen, but also by Grigori Tchitcherine, a former dancer with Dutch National Ballet and, since 2001, a teacher of classical ballet and character dance at the Dutch National Ballet Academy.

Tchitcherine – who trained at the famous Vaganova Ballet Academy in St Petersburg and went on to dance with the Mariinsky Ballet for five years – was more or less brought up on Raymonda. “As a boy of eleven, I was already dancing in the Arabian boys’ dance in the production by the Mariinsky Ballet. And I was already under the spell of Raymonda in those days.” Beaujean says, “Grisha (as Tchitcherine is known by his colleagues – ed.) has the knowledge of an archivist. He knows everything about the history and the various productions of the ballet.”

Initially, Beaujean and Tchitcherine thought that the original notation of Petipa’s ballet from 1898 – made by Vladimir Stepanov and stored in the archives of Harvard University – would prove essential for creating their new Raymonda production. But after Tchitcherine had managed, with some difficulty, to get hold of it, the notation turned out to provide much less clarification and value than they’d expected. Beaujean explains, “People always speak highly of that Stepanov notation. Many choreographers say they’ve used it in reconstructing the great classical ballets, but I think that in nearly every case it was mainly a publicity stunt.” Tchitcherine adds, “Stepanov’s notes are very sketchy and consist mostly of a few lines and arrows. At most, you see where the dancers stood on stage at the time, but not what the choreography looked like or its style.”

Living art form

In the end, the two concluded, the choreography as still danced by the Mariinsky Ballet is probably the closest to Petipa’s original. Beaujean says, “So we took that as our starting point.” Tchitcherine says, “Although nobody can say for sure which parts are still by Petipa and which are by Konstantin Sergeyev, who adapted the production in 1948 for the Mariinsky. Sergeyev did want to remain as faithful as possible to Petipa, but he also tailored the ballet to the times in which his version was created. He made changes to the order of the libretto and added new choreography, whereby he also ‘borrowed’ material from others.” Beaujean says, “That’s more or less what I did too. Sometimes I had to adjust certain steps a bit, because they didn’t fit the feeling I want to convey. And some parts – including the variations for Abd al-Rahman and the love pas de deux in the vision scene and at the end of the second act – required totally new, or mainly new choreography. Each scene was preceded by endless deliberation. It was one big adventure. Sometimes, I’d go into the studio a bag of nerves, but fortunately I’d always feel relief after finishing a section, in the knowledge that another egg had been laid”

It was anyway never Beaujean and Tchitcherine’s intention to create a faithful reconstruction of Petipa’s masterpiece. Beaujean says, “Ballet is a living art form. You have to make adjustments to dynamics, tempo and virtuosity, otherwise today’s audiences would be bored to tears.” Tchitcherine agrees, “Presenting ballet as it was in Petipa’s day is like returning to silent movies.”

Musical puzzle

On top of that, Beaujean’s intervention in the storyline also gave rise to an enormous musical puzzle. Beaujean says, “In Alexander Glazunov’s composition for Raymonda, each character has their own leitmotiv, in the style of Wagner. That means you can’t just switch around the scenes as you like. For four months, I worked with Grisha, first pianist Olga Khoziainova and musical director Matthew Rowe on a new compilation of the music sections. We were continually weighing up what I thought was necessary and what they thought was acceptable. In other words, what can you tinker with and what must you leave exactly as it is?”

One blessing in disguise was that Petipa and Glazunov themselves were not enamoured of the original libretto by Lydia Pashkova, so they’d already made changes to the storyline and added sections. “So the composition is not as sacred and intact as, for example, the music of the second act of Giselle.”

Elegant and timeless

Early on in the creative process, Beaujean already knew that she wanted the sets and costumes for her new Raymonda production to be designed by the Frenchman Jérôme Kaplan, who had made his debut with Dutch National Ballet in 2010, with his designs for Alexei Ratmansky’s highly acclaimed Don Quixote. Beaujean says, “At the time, my continually gaming sons said they thought the scenery was so beautiful and so graphic, and that in a certain way it made the production modern, even though Don Quixote takes place sometime in the eighteenth century, in Spain.

I realised that I wanted the same look and feel for Raymonda. If a work of art is good, then it’ll still be around a hundred years later, like Petipa’s ballets, and it should have designs of the same quality. Jérôme’s work has that quality! For Raymonda, he’s designed a wonderful, imaginative representation of the Middle Ages, and so – with regard to the costumes – he doesn’t have everyone walking around in those stiff mediaeval pointed hats. His designs are refined and classical, yet at the same time elegant, chic, colourful and timeless.”

Star team

With Kaplan and all the other artists who worked on the creation of this new Raymonda production at her side, Beaujean says she could pride herself on a ‘star team’. “We drew on all the expertise we have to hand. Grisha, for example, was not only a huge help in my research into the history of Raymonda, but was also responsible for rehearsing the character dances in the second act. Boris Gruzin – who’s conducted countless performances of the ballet for the Mariinsky Ballet and the Bolshoi Ballet – put together our new sequence of Glazunov’s music sections and gave his seal of approval to the whole. Janine Brogt, who previously wrote the librettos for Ted Brandsen’s Coppelia and Mata Hari, assisted me with dramaturgical advice. Former principal dancer Larissa Lezhnina, who also danced with the Mariinsky Ballet for years, joined ballet master Guillaume Graffin in rehearsing the Grand Pas Classique, and for the sword fights we engaged ‘fight choreographer’ and stuntman Youval Kuipers. Raymonda is not the work of one or two people. It takes a whole ‘village’ to create such a large-scale production.”

Cherishing the classics

Looking back, Beaujean is ‘incredibly grateful’ that Ted Brandsen gave her the opportunity to create this new production of Raymonda, following her earlier adaptations of other famous classics. Because although she was mainly known during her dancing career as the muse of Hans van Manen, she has a big soft spot for the nineteenth-century Russian dance heritage. “I think it’s really important that we cherish the great classics. I grew up with that mentality in my time with Dutch National Ballet as well. Former artistic director Rudi van Dantzig really loved ‘the Russians’ (the Russian ballerina Galina Ulanova, for example, was an important source of inspiration for his Romeo and Juliet – ed.), and I soon came to understand that if you want to help develop the art of ballet further, you can’t ignore that incredibly rich Russian tradition; that gigantic artistic legacy. Yet I do feel afraid that it might all disappear. Nineteenth-century classical ballet is a very vulnerable art form, as it’s so specific and demands so much discipline and dedication from the dancers. And because it requires so much in the way of expertise and financial resources to present top-quality productions. So even if it were to be the last contribution I could still make, I’ve taken on the task of devoting myself to preserving the classics and the enormous history behind them for posterity.”

Text: Astrid van Leeuwen

Alexander Glazunov: the musical bridge between east and west

The music for Raymonda

Alexander Glazunov: the musical bridge between east and west

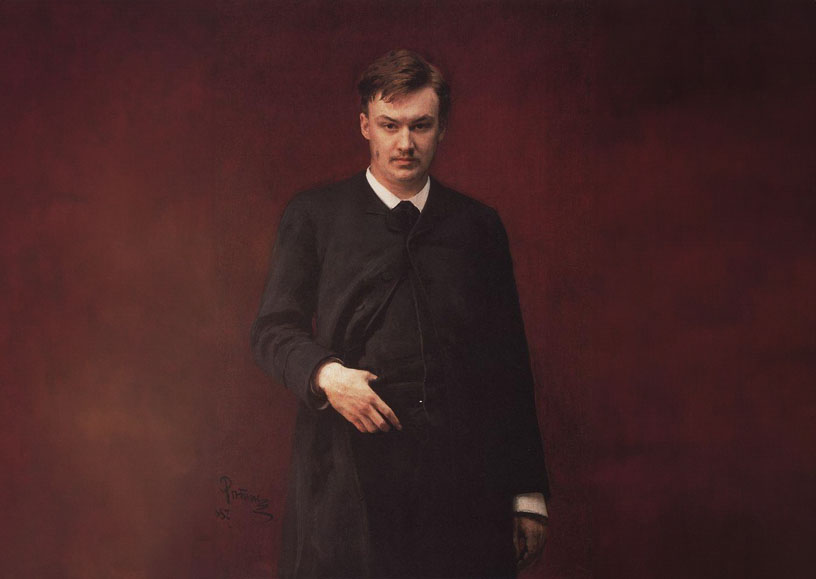

The Russian composer Alexander Glazunov was an expert in reconciling nationalism and cosmopolitanism in music. His characteristic composition style is also clearly heard in his first ballet, Raymonda. In close collaboration with Marius Petipa, he created a ballet that grew to become a true masterpiece.

When Alexander Glazunov was born in 1865, the composition profession in Russia was dominated by a few composers know as ‘The Mighty Handful’. The five members – Mily Balakirev, Alexander Borodin, César Cui, Modest Mussorgsky and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov – were autodidacts and fervent supporters of a national musical style. According to them, composers were supposed to take inspiration from Russian folk music and stories from the motherland. They looked down on academic music education, such as that received by their contemporary Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. Such education was associated with the West, which was at odds with the authentic Russian music culture.

Musical prodigy

While Alexander Glazunov started relatively late by the standards of musical child prodigies – the average being around six-and-a-half – a first attempt at composition at the age of eleven is an exceptional achievement. His talent did not go unremarked by Balakirev, who asked Rimsky-Korsakov to guide the young composer. Under his wing, Glazunov developed rapidly, and in the words of his master, “made progress not daily, but literally hourly”. After just under two years of private lessons, he had learned more or less all he could. He was no longer a student, but a fellow composer.

Russian national style

The musical formalities studied by Glazunov during his private training soon became a blueprint for the Russian national style. But what actually makes music Russian? A piece composed by a Russian composer? Does it come from a particular rhythm, or a specific melody or harmony? Compared to the West, Russia was relatively late in developing its own tradition of classical music. A turning point came when Tsar Peter the Great introduced radical political and cultural changes in the eighteenth century. Although Peter the Great was not too fond of music himself, he regarded European music as a sign of civilisation and saw it as a means of westernising the country. He invited Western composers to come and inspire the composers of his own country.

Western art music became a huge rage in Russia, to the point where people were hardly aware of the existence of Russian composers. The focus on European music meant that Russian composers had to adopt the Western style if they wanted their compositions to actually be performed. Halfway through the nineteenth century, however, doubts arose about whether Russian classical music ought to be composed in accordance with Western standards. The ‘father of Russian music’ Mikhail Glinka, and young composers like the members of ‘The Mighty Handful’, started a new musical tradition, in which they took inspiration from folk music and stories. The musical idiom they developed was based on two elements. On the one hand, they were inspired by the sounds and rhythms of village songs, Cossack and Caucasian dances, and hymns. On the other, they invented new harmonic constructions to create a distinctly Russian style and timbre. The new harmonic conventions had little to do with Russian authenticity, but at least they were not Western – and that was a goal in itself.

Duality

The musical ideals of ‘The Mighty Handful’ were taught to and impressed on Glazunov from an early age. Although he was regarded as their musical heir, Glazunov became increasingly influenced by Tchaikovsky and by Western composers. On turning twenty, he came to realise that the battle between the academic West and the nationalist East was no longer worth the effort. His music became more individualistic and melodious, and brimmed with talent. Before writing the music for Raymonda, Glazunov had composed the dance suite Scenes du Ballet, which demonstrated his ability to combine the folklore, nationalist style and the more cosmopolitan, Western-oriented style in his music.

One man’s breath is another man’s death

On seeing the Petipa-Tchaikovsky trilogy, Glazunov swore that one day he would create his own ballet in the same grand style and tradition. Scenes du Ballet and his adaptation of the short ‘ballet blanc’ Les Sylphides were just a foretaste of how he wanted to use his expertise and skills. Following the sudden death of Tchaikovsky, Marius Petipa was forced to look for a new composer. In the spring of 1896, Glazunov finally got the commission his heart longed for: composing the music for Raymonda. He did not let the fact that he had not yet received a libretto stop him. In his enthusiasm, he began to write furiously straight away.

While he was composing the music, Glazunov worked closely with Petipa, who gave him a very detailed plan of each scene – complete with specific tempos and time signatures, and the precise number of repeats. It was not that he did not trust the composer, as he had given similar checklists to Tchaikovsky. It gave Glazunov the opportunity to understand the nature and emotion of the choreography. Within the strict limitations of the set choreography, he managed to compose music of an intense, lyrical sensitivity. Through the close collaboration between choreographer and composer, the music for Raymonda does not play a subordinate role, as was often the case in classical ballets at the time, but the composition and the choreography complement one another.

Despite the instructions he was given, Glazunov still succeeded in putting his own, unique mark on the composition for Raymonda. The melodies and timbres pay tribute to the Tchaikovskian tradition, and are sometimes reminiscent of passages from Swan Lake and The Sleeping Beauty. Yet he did not renounce his roots: the national style taught to him from an early age. Raymonda has harmonies with folk references that recall the musical idiom of ‘The Mighty Handful’. The musical synthesis between East and West also remains an unmistakable element in his other compositions, and he thus bridges the gap as no other composer had done before him. The life and compositions of Alexander Glazunov still continue to arouse admiration for and interest in this once celebrated composer.

Text: Stan Schreurs

‘A salad of styles’

A glimpse into the ‘kitchen’ of set and costume designer Jérôme Kaplan

‘A salad of styles’

A nineteenth-century Russian ballet set in France and Hungary in the Middle Ages, which includes dance styles ranging from supremely classical ballet to sword fighting dances, Arabian dances and Eastern-European folk dances: in every respect, Raymonda is a product of very diverse influences. Costume and set designer Jérôme Kaplan took on the challenge of bringing together all these styles and historical details in the decor for the ballet.

In doing so, Kaplan set himself the goal of creating a historical setting with a fresh look. He says, “Some people think that classical ballet always stays the same, but in order to keep it alive, you actually have to keep adapting and changing things. And that includes the sets and costumes.”

Bright colours and refined patterns

For Raymonda, this meant that Kaplan had to depart from the style of the original nineteenth-century ballet. “In those days, the idea of what things must have looked like in the Middle Ages was very different to how we see the period nowadays, partly due to archaeological findings. So the sets and costumes of the original ballet by Marius Petipa are pretty dark and are rather Gothic in character. As we now have a more complete, and thus more realistic picture of the Middle Ages, the style of our Raymonda is a bit different: the colours are brighter and the patterns more refined.”

However, this doesn’t mean that the nineteenth-century influence is completely absent from Kaplan’s designs. “It remains important to preserve the best aspects of the original ballet. Moreover, it’s impossible to completely ignore the nineteenth-century style, if only for the big role played by the tutu. Although the tutu didn’t exist yet in the Middle Ages, you can’t get around it in classical ballets like this one.”

Pre-Raphaelism

Kaplan eventually found the middle road between the time when the story of Raymonda takes place and the period when the original production was created: Pre-Raphaelism – a nineteenth-century art movement characterised by a great interest in the Middle Ages. Kaplan says, “As Pre-Raphaelism arose in the nineteenth century, yet focuses on the Middle Ages, this movement makes it possible to look at the nineteenth-century style through a mediaeval filter.”

But he needed more than just Pre-Raphaelism as his source of inspiration. “A huge number of different influences come together in Raymonda, besides the atmospheres of the Russian nineteenth century and the French Middle Ages. A major role is also played by Hungarian and Eastern-European influences. And then you also have Abd al-Rahman and his retinue, who come from the Middle East and lend an exotic touch to the production with their Arabian costumes.”

Like cooking

All these influences, says Kaplan, make Raymonda a ‘big salad of styles’. “I often compare designing to cooking”, he laughs. “You gather top-quality ingredients and combine them in a dish to which you add your own personal taste. Those ingredients come from all over the place. For instance, the palace in the first act is based on the Papal Palace in Avignon, the only mediaeval palace still found in the South of France. And the inspiration for the Hungarian costumes came from an old book found by a friend of mine at a flea market in Hungary.”

Tasting

The next challenge is to ensure the end result stays clean. “Because if you have to incorporate so many historical details in one production, you run the risk of losing your way in them. You have to pay enough attention to these details – from the embroidery on a dress to the buckles on a boot – but at the same time you have to retain a view of the whole. That’s not always easy, but I think it helps that I’m designing both the sets and the costumes for this production. That means I can zoom in on details while also keeping an eye on the whole from a certain distance.” During the stage rehearsals, Kaplan literally looks at it from a distance. “It’s only then that you really see what the designs look like. You have to try things out before you can decide whether to make cuts, additions or adjustments. That’s just like cooking too. You have to taste it first before you can decide whether to add more salt.”

In his ‘kitchen’, Kaplan collaborates closely with the rest of the artistic team responsible for the production, including Rachel Beaujean, Ted Brandsen and head of the costume department Oliver Haller. “That’s one of the reasons I love designing the sets and costumes for ballets: you work together on a wonderful ballet production and everyone wants it to be a big success. My aim as a designer is therefore not to present the latest ‘Kaplan creation’ on stage, but to contribute to a successful Raymonda, such as I’d enjoy watching as a member of the audience.”

Rosalie Overing

‘The sword fight sums up the key point in the new dramaturgy’

Youval Kuipers about the fight choreography for Raymonda

‘The sword fight sums up the key point in the new dramaturgy’

Probably the most exciting moment of the story of Raymonda takes place in the second act: the confrontation between Jean de Brienne and Abd al-Rahman, which ends in a gripping sword fight. To give the right feel to the fight and make it as historically accurate as possible, Rachel Beaujean called on fight choreographer Youval Kuipers. Kuipers says, “Rachel and I speak the same language. Even though we come from different circles, we have the same goal: to tell a story through movement.”

His choreography for the sword fight between Jean de Brienne and Abd al-Rahman underwent thorough analysis beforehand. Kuipers explains, “My choreography is based on reconstructions of mediaeval European fighting styles that come from books on fighting of the day. They’re manuscripts in which weapon masters use drawings to systematically explain how someone can defend themself with all sorts of weapons within a particular fighting style. This allows you to completely reconstruct a mediaeval fighting style from start to finish. From these manuscripts, we also know that European fighting styles were very refined, technical and practical, with a special aestheticism that lends itself well to spectacle.”

Each fighting style has its own historical weapons. “Whereas traditional productions of Raymonda often use light fencing swords and a stylised way of fighting, for this production I wanted to use a historical fighting style, with specific weapons that were used in that period,” Kuipers says. “For Raymonda, which takes place in the eighth century, those are one-handed swords similar to Viking swords. This creates a new, exciting and spectacular element that people aren’t used to seeing in a classical ballet.”

Blend

For Kuipers, who usually works as a fight choreographer on film sets and for stunt shows, it was a whole new experience to choreograph the fights for a classical ballet. “I’m used to creating fights for films, where the music is only composed afterwards. But now the composition was already there, so I had to ensure that the main points of the fight coincided with the music with regard to rhythm and structure.” Working with dancers also gave rise to a refreshing interaction. “Dancers have so much movement experience and are used to making unfamiliar movements fit their own body. I could even leave parts of my choreography up to them. So together, we devised ways of magnifying certain actions by letting the energy of one character’s attack flow into another. By learning from one another, we created a blend of the arts of dancing and fighting, so that the fight scene fits seamlessly into the rest of the ballet. It was a very special experience, for which I’m incredibly grateful to Dutch National Ballet.”

A fight like a micro-story

Kuipers thinks it’s important that the fight scenes serve the story, rather than just being used for spectacular effect. So the dramaturgy for Dutch National Ballet’s production – in which Raymonda chooses Abd al-Rahman over Jean de Brienne – is also reflected in the sword fight between Jean de Brienne and Abd al-Rahman. “In life or death situations, you see the true nature of a person. So this fight had to expose the true nature of the two men. While the hot-headed Jean starts the fight, Abd al-Rahman tries to avoid the fight like a true nobleman.”

Raymonda, too, who is more self-determined in this version of the story, gets an interesting role in the fight, says Kuipers. “Whereas Raymonda was originally a bystander who didn’t want to get mixed up in the ‘male world’ in front of her, in this production we’ve let her play an active role in mediating the conflict. When she also effectively becomes physically involved in the fight, by obstructing Jean’s weapon, he pushes her aside and hurts her, whereas Abd al-Rahman catches her. This, of course, immediately clarifies Raymonda’s choice for Abd al-Rahman. In this way, the fight choreography sums up the key point in the new dramaturgy: the male roles of nobleman and angry barbarian are swapped around, and Raymonda is more self-assured then ever.”

It is precisely that narrative capacity that Kuipers likes about fight choreography. “A fight is actually a micro-story, with a beginning, a middle and an ending – just like a ballet story. The fact that these disciplines are now coming together in a new ballet production is unique.”

Text: Eline Hadermann

programmaboek

Become a Friend of Dutch National Ballet

As a Friend, you support the dancers and makers of Dutch National Ballet. You are indispensable to them and we are happy to do something in return. For Ballet Friends we organize exclusive activities behind the scenes. You will receive the Friends magazine from us and you will receive priority when ordering tickets.