The Four Note Opera

Performance information

Voorstellings-informatie

Performance information

The Four Note Opera

Tom Johnson (1939)

Duration

70 minutes

The performance is sung in English

There are no surtitles

Libretto

Tom Johnson

Stage direction

Kenza Koutchoukali

Musical direction

Alejandro Cantalapiedra

Scenography and costumes

Yannick Verweij

Lighting design

Coen van der Hoeven

Dramaturgy

Laura Roling, Wout van Tongeren

Performed by artists of the Dutch National Opera Studio:

Soprano

Sophia Hunt

Alto

Martina Myskohlid

Tenor

Salvador Villanueva

Baritone

Georgiy Derbas-Richter

Bass

Mark Kurmanbayev

Pianist

Daniel Ruiz de Cenzano Caballero

Coproduction of Dutch National Opera with the Nederlandse Reisopera and Opera Zuid

Production team

Assistant director

Maarten van Grootel

Vocal coach / Head of Dutch National Opera Studio

Rosemary Joshua

Language coach

William Kelley

Movement coach

Maarten van Grootel

Masha Zhukova

Director during performances

Maarten van Grootel

Rehearsal pianists

Amy Chang

Daniel Ruiz de Cenzano Caballero

Stage manager

Roy van Zon

Artistic planning

Sonja Heyl

Master carpenter

Trinus Hertroijs

Props manager

Niko Groot

Sound technician

Juan Verdaguer

Head of the music library

Rudolf Weges

Set supervisor

Sieger Kotterer

Production management

Maaike Ophuijsen

In a nutshell

Korte inhoud

In a nutshell

The Story

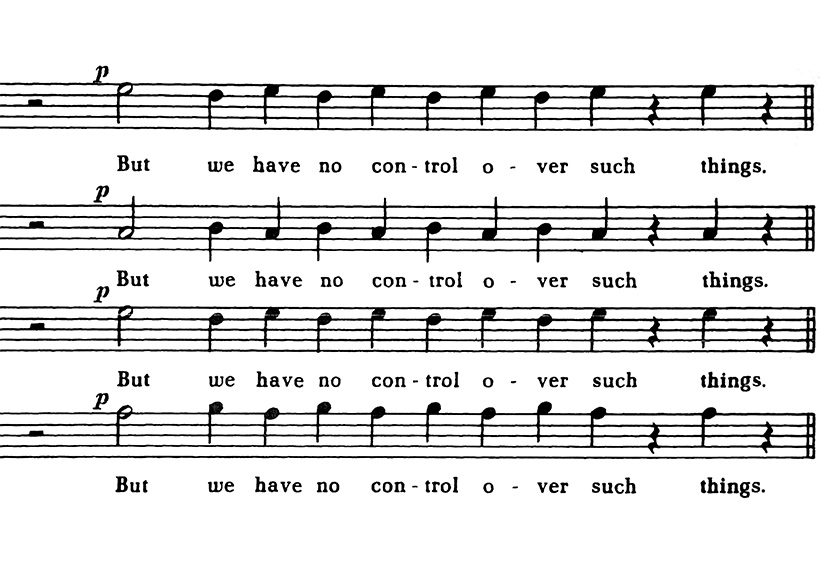

A group of opera singers and a pianist only have four notes at their disposal — A, B, D and E — and they are unable to sing about anything except the opera they are currently in. In a series of choruses, recitatives, arias, duets, trios and a quartet, they embody the clichés and the rigidity of the traditional opera world. They cannot influence what they are doing. “That is the way the opera is written – we have no control over such things” is a recurring phrase that says it all. The situation becomes untenable and the opera ends in complete paralysis.

Showcase for young singers

The Studio Ensemble of Dutch National Opera’s predecessor was responsible for the European premiere of The Four Note Opera in 1975. Over fifty years later, the work is still a wonderful showcase that lets singers display not only their vocal capabilities but also their acting skills. That makes the work a nice challenge for the young performers of Dutch National Opera Studio, the opera house’s talent development programme.

Minimalism

Composer Tom Johnson (1939) is a musical minimalist. His compositions often revolve around the consistent application of rules. In The Chord Catalogue, for instance, he systematically arranges all 8178 chords possible within the octave c-c1. And in Music for 88, he applies various mathematical number theories to the 88 keys of a piano. His oeuvre is characterised by both rigidity and playfulness.

“I always feel very uncomfortable in the Final Scene.

But what can we do?

That is the way the opera is written.

We have no control over such things.”

From The Four Note Opera

Theatrical exploration with horror elements

For this production of The Four Note Opera, director Kenza Koutchoukali and designer Yannick Verweij spent several weeks in the studio working with the young performers of Dutch National Opera Studio. The team looked for ways of using this rigid opera, which runs the gamut of clichés about opera singers, to show the damage done to the individual by certain systems — such as the ‘opera system’ ridiculed in The Four Note Opera. The horror genre turned out to be a fruitful approach. Horror films are grotesque, gruesome and sometimes laughable, but they also have a long tradition of social criticism and engagement. Kenza Koutchoukali: “Exaggerating as a way of questioning problematic systems is what we do too, and we play with that idea.”

Red dominates run-down theatre set

The artistic team for the design aspects have used a lot of blood and the colour red: red velvet, red stage curtains, red carpet. “Red is the colour of theatres, but also the colour of blood and suffering,” explains designer Yannick Verweij. The team also looked for ways to make the connection with the outside world, to show that while the opera singers might have no control over their performance in The Four Note Opera, they could have something interesting to say if only they were given the opportunity.

‘Aren’t operas like this a kind of horror story?’

The stage director Kenza Koutchoukali and designer Yannick Verweij on the process of creating The Four Note Opera

The production’s stage direction and design were subject to last-minute alterations. This means that certain details in the interview with stage director Kenza Koutchoukali and designer Yannick Verweij are no longer entirely correct.

‘Aren’t operas like this a kind of horror story?’

The Four Note Opera has no plot, the characters have nothing to say except what they are singing and the outside world seems not to exist. It is a satire on operatic clichés from fifty years ago and it is somewhat dated in its criticisms. How does a young, engaged opera director tackle that?

Kenza Koutchoukali has struggled a great deal with that very question, she admits in the green room some two weeks before the premiere. “The work is a critical satire on opera as a genre. In 1972, it was probably really interesting and topical but fifty years later it is no longer so relevant for an opera house like ours that prioritises creativity and innovation. So I asked myself what I could say with this opera today, in 2024.”

From the start of her career, she has been working with the scenographer Yannick Verweij, whom she calls ‘an intelligent maker’ and far more than ‘merely’ a designer. He is someone who can help her reflect on the concept and stage direction. He in turn calls Koutchoukali someone who ‘thinks visually’, draws on the design and uses that to develop her ideas for the production. It is a complementary partnership, as is clear during the interview: they constantly swap roles and add to what the other is saying.

In the summer of 2023, Koutchoukali was asked to do a project with the singers of Opera Studio. The idea was to have a small-scale opera, a co-production of Dutch National Opera with Nederlandse Reisopera and Opera Zuid. In the end, The Four Note Opera was chosen. Despite her initial doubts, Koutchoukali decided to investigate what she could say with this curious opera about operatic conventions. Which ultimately also poses the question: what power does opera have anyway?

Satirising dominant opera practices

The Four Note Opera was written in 1972 as a satire of dominant opera practices, running the gamut of all the clichés. It consists of a series of arias, recitatives and choruses using only four notes: A, B, D, E. The libretto is almost exclusively a commentary on what the music is doing. It embodies the lack of freedom and agency of the characters, for example in the final scene:

I always feel very uncomfortable in the Final Scene.

But what can we do?

That is the way the opera is written.

We have no control over such things.

Koutchoukali: “The opera plays with the rigidity of the classical opera structure, with a bombastic opening chorus, endless repeats and clichéd relationships between the singers. I don’t find Tom Johnson’s criticism of opera, as expressed in this work, all that relevant anymore. And I certainly didn’t want to criticise the singers or opera singing as a profession. We therefore thought it might be interesting to have the singers protesting against the work and the way they are at the mercy of the whims of the composer or the artistic team. That approach offers a lot of possibilities.”

The opera system

“Another perspective we find relevant is the fact that opera houses still operate rigid systems even today — as is the case in many different areas throughout society. An opera house is a ponderous, cumbersome institution. Many things are decided years in advance, and it is not easy to determine your position as an individual within that institution. While a lot has changed compared with the period when The Four Note Opera was written, I still regularly see operas with a woman wearing a negligée being taken from behind, to give an example. We’ve seen progress in that regard, but there is still plenty of room for improvement in terms of problematic representations of gender, colour and so forth.”

Verweij: “Kenza is an engaged creative who wants her work to have a relevant message. “So what do you then do with an opera that is so focused on itself? It’s difficult to find a way in. I wanted to come up with possible ideas by looking at the design aspect. Over the past few years as a designer, I have increasingly become specialised in assisting in complex creative processes. I try to give the director tools that will help them develop an interpretation, for instance by giving them really concrete assignments.”

In overdrive

Koutchoukali: “In this opera, the singers produce clichés in both their music and their texts. You can let them do that without commenting on it, and that would probably work too, but I wanted to go into overdrive. We tried that and it immediately felt alienating to us. The starting point is still the essence of the material but we also show the absurdity of it, almost as if the singers have been singing this same opera for fifty years. There is a very comical aspect to that. As soon as the lights go on, the show starts rolling once again! Performing! That overdrive reminded us of horror as a genre. “Exaggerating as a way of questioning problematic systems is what we do too, and we play with that idea. Aren’t operas like this a kind of horror story?”

Verweij: “That offers plenty of possibilities too for the set concept. We’ve used a lot of blood and the colour red. Red velvet, red stage curtains, red carpets: sure, red is the colour of theatres, but it’s also of blood and suffering. We also want to refer to the outside world without laying it on with a trowel. We’re still figuring out how to do that. At the moment, we have the singers producing pamphlets when they aren’t in action to see whether that approach might work.”

Koutchoukali: “The singers are enjoying the piece more and more and they feel more autonomy. We have also thought up various workshops for them. For example, Francis van Broekhuizen ran a workshop on how to feel free in your acting, the dancer Masha Zhukova has organised workshops on movement and we are working with the intimacy coordinator Markoesa Hamer for the scenes that require that.”

Verweij: “The Green Deal is an important factor in the design. DNO wants to reuse materials wherever possible, and rightly so. We’re using the glass ‘cabin’ from Ändere die Welt, and together with the Production Workshop, I’m looking for specific decor elements that would work well in a theatrical setting like this. Our lighting designer Coen van der Hoeven has designed some nicely theatrical lighting and we use a lot of smoke. We want it to look like a slick musical at times.”

Four Note Experiment

Koutchoukali: “I said to Sophie de Lint that I wanted to tackle this project as an experiment and she was all for it. What I mean by that is not having a fixed concept in mind beforehand but going into the studio with ideas and materials. Nothing was decided. However, we did discover along the way that there we didn’t have much experience of facilitating experimental processes like this. Different constraints apply in Studio Boekman compared with projects for the main theatre, and that takes some getting used to. Yannick’s initial idea was to have the singers constantly interrupted and drawn out of their comfort zone by a disturbance off stage, but at the last minute that turned out not to be feasible for technical reasons. In the end, we decided to work with old-school opera references, such as a draped red curtain, a chandelier and other elements that recall a traditional if rather dilapidated opera house. Everything feels outdated and remote.”

Koutchoukali: “But we didn’t want to use comical clothes from the dressing-up box for the costumes. We wanted it to have a certain minimalism, not standard comic theatre. We let the singers act out certain opera clichés by giving them physical instructions. You can suggest a lot with lighting and movement. Of course, we play with the contrast between what is ‘real’ and ‘not real’, the laws of theatre. Do the characters imagine that they are really performing the greatest opera of all time or do they feel pressurised to pretend that they are?”

Opera clichés

“We also play with opera clichés in the distribution of the roles. Examples are the tenor who doesn’t get a solo or the assumed rivalry between the soprano and the mezzo-soprano. In the classic repertoire, the soprano always gets the main role and that inevitably leads to rivalries behind the scenes. We magnify that dynamic in our horror-themed approach. As a genre, horror is always an exaggeration of some problematic issue and that links back to our exploration of opera as a system: rivalries, misogynistic and so on. We hope this will make the opera accessible to new audiences as well as veteran opera lovers who will be amused by this absurd romp through the clichés.”

Two weeks before the montage, Koutchoukali wondered, “Can a work that isn’t about anything still be about something? And does it even have to be? It is precisely that question – that friction – that I’ve felt from the start, that I can investigate with this experiment and this production.”

Verweij: “That dilemma for Kenza and the whole team is really about questions of how they should operate in the opera world and how to make sure the wider world gets acknowledged. It mustn’t be engagement purely for show; we want a genuine connection with what is going on in the world. Precisely that contrast between escapism and engagement is interesting.”

Text: Margriet Prinssen

‘Opera characters looking for a composer’

Composer Tom Johnson on The Four Note Opera

‘Opera characters looking for a composer’

In 2004, composer Tom Johnson wrote the following reflection on The Four Note Opera (1972) and his work as a composer.

I was 32 years old when The Four Note Opera was premiered, and that was 32 years ago. Now, with the wisdom one is expected to have at the age of 64, I should know everything about this early work, but I really don’t know much more than before. The only sure thing is that the crucial moment in the evolution of the piece was that evening very long ago when I read, with great excitement, Luigi Pirandello's Six Characters In Search of an Author. Normally characters are not even conscious of their existence on a stage. They are completely obedient to the author, they conform totally to the world the author creates, and they have no thoughts of their own. But Pirandello's masterpiece was different. His characters knew they existed in a theatrical space, and only for a couple of hours. They were aware of the audience, and of the author as well. It was not the kind of theatre that asks you to believe something that is not true. It was the kind of theatre that you have to believe, because everything is true.

Pirandello's vision had a strong impact on me, and for years one question lingered in the back of my mind: what would happen if, instead of Six Characters in Search of an Author, there happened to be some opera characters looking for a composer? It happened that some opera characters were looking for a composer, and about 10 years after reading Pirandello they found me and came to life in The Four Note Opera. This opera, my first, was premiered in 1972 in a little theater in New York called the Cubiculo, and it was an immediate success, taken over later that year by CBS-TV, then by the Netherlands Opera for a European premier the following season, and subsequently by other opera groups, both professional and non-professional, each year thereafter.

Naturally, I thought that writing other successful operas would be easy, now that I had such a good start, so three years later I wrote The Masque of Clouds, which really was a masque, with clear references to Elizabethan traditions. The main characters were the Lake (mezzo), the Forest (baritone), and the Clouds (two coloraturas), and they all had nice arias, and the idea might actually have worked if we had had a big budget and a large orchestra, but trying to do such a thing in a modest quick way was destined for disaster. The work has never been staged since.

I had always loved the American tradition known as "shaggy dog stories," those repetitive stories that take a very long time to tell until they finally end with some dumb punch line, usually a simple word play or an ironic remark, so my next operatic attempt, in 1978, went in that direction. The result was five chamber operas, about 15 minutes each, which I staged myself in a small loft space in lower Manhattan. This was also less successful than The Four Note Opera, though three of these short operas are still done from time to time: Drawers, in which a solo soprano searches for her thimble, Dryer, in which a fisherman catches fish and hangs them on the clothes line to dry, and Door, in which two women sing "yawn" a lot, and wonder whether they should answer the door.

Next came Sopranos Only in 1984, which is basically a procession for six sopranos, accompanied by flute, violin, harp, and cello. With so many sopranos in the world, there is always a need for new soprano roles, and this 35-minute piece does serve a function- most often in workshops in American universities and conservatories.

But a real success story began in 1988 with the premiere in Bremen of Riemannoper: a full evening piece for four singers and piano, with libretto extracted exclusively from the Riemann Musik Lexikon, the German equivalent of the Groves Dictionary of Music. German musicology is terribly serious, and the definitions are extremely terse and precise, so the results are bound to be amusing when singers do exactly what the text says. Take the dictionary definition of aria di bravura, for example: Durch die Aria di bravura werden Wut, Rache und Triumph ausgedruckt. (The Aria di bravura expresses rage, revenge, and triumph.) So the baritone sings one verse of "rage rage rage," another of "revenge revenge revenge," another of "triumph triumph triumph," and there you have it. Riemannoper is essentially untranslatable, so it appears only in places where audiences understand German, but its 28th staging was launched in Halberstadt recently, and some years it is performed more than The Four Note Opera.

Still, The Four Note Opera is the long term success, with six or eight translations and at least 70 different stagings that I know of. I have only seen a tiny percentage of these interpretations myself, but these have provided me with a lovely bank of memories. I recall particularly well, for example, the world premiere night in that little theater, with about 15 people in the audience, almost all personal friends, and how surprised we were that the house was sold out the following weekend. I remember the French premiere, directed by Henry Pillsbury at the Festival d’automne in Paris in 1982, with rather slow tempos and a particular French elegance. I remember a staging in Padua in 1984, with a stage set consisting simply of colored cubes, and with a real chorus of 40 volunteers. Nor will I ever forget the performance in Poland, where a young tenor with the Warsaw Chamber Company sang so beautifully that I could hardly forgive myself for not having given him a second aria. The memories continue to accumulate, and two recent stagings surprised me all over again. One of my favorite moments in the Pavana production in Valencia was the 40-bar duet, presented as an intense 40-card poker game. Why didn’t other stage directors ever think of that? An equally original and stimulating moment was the final scene, as mounted by the Atelier Lyrique de Franche Compté. The faces of the four singers peered through four holes of a painted panel, suggesting the four notes, but also suggesting that they were prisoners locked into scaffolds. The same image, without the faces, was also the poster advertising the production.

The opera has quite a different look each time it is mounted, and indeed, the success of The Four Note Opera no doubt has much to do with its flexibility. Each new cast changes the characters, each new designer changes the look, and the result is always fresh. My composing in the past 10 years has been more abstract, often mathematically based, and I don’t follow these new transformations of The Four Note Opera very much anymore, but then, the piece is 32 years old now, and like any 32-year-old, it must now make its own way. There is really nothing more a father can do.

Text: Tom Johnson

Bekijk hier de printversie van het boek