Innocence

Content

Performance information

Voorstellingsinformatie

Performance information

Innocence

Kaija Saariaho (1952-2023)

Duration

1 hour and 45 minutes, no interval

The main singing language is English, and additional languages are Finnish, Czech, French, Romanian, Swedish, German, Spanish and Greek.

Dutch surtitles based on the translation by Jasmijn van Wijnen, and English surtitles based on the translation by Aleksi Barrière.

Opera in five acts and one epilogue.

Makers

Libretto

Sofi Oksanen (original Finnish) & Aleksi Barrière (multilingual version)

Musical direction

Elena Schwarz

Stage directions and dramaturgy

Simon Stone

Set design

Chloe Lamford

Costume design

Mel Page

Lighting design

James Farncombe

Choreography

Arco Renz

Dramaturgy

Aleksi Barrière

Cast

The Waitress (Tereza)

Jenny Carlstedt

The Mother-in-Law (Patricia)

Lenneke Ruiten

The Father-in-Law (Henrik)

Thomas Oliemans

The Bride (Stela)

Lilian Farahani

The Bridegroom (Tuomas)

Markus Nykänen

The Priest

Frederik Bergman

The Teacher

Lucy Shelton

Markéta (student 1)

Vilma Jää

Lily (student 2)

My Johansson

Iris (student 3)

Julie Hega

Anton (student 4)

Rowan Kievits

Jerónimo (student 5)

Camilo Delgado Díaz

Alexia (student 6) Olga Heikkilä

Residentie Orkest

Chorus of Dutch National Opera

Chorus master

Edward Ananian-Cooper

Composition commission and co-production

Dutch National Opera, Festival d’Aix-en- Provence, Royal Opera House (London), Finnish National Opera and Ballet and San Francisco Opera

In collaboration with The Metropolitan Opera (New York)

Production team

Staging

Louise Bakker

Assistant director and assistant director during performances

Isabel Schröder

Junior assistant director

Hasse van der Veldt

Assistant conductor

Leonard Elschenbroich

Rehearsal pianists

Jan-Paul Grijpink

Frédéric Calendreau

Assistant chorus master

Lochlan Brown

Language coaches

Stephan Rehm (Duits)

Iida Antola (Fins)

Stage managers

Merel Francissen

Marjolein Bergsma

Pieter Heebink

Jossie van Dongen

Artistic planning

Emma Becker

Orchestra inspector

Harm Jan Schwantje

Evelien van der Weijden

Nadia Frissen

Master carpenter

Edwin Rijs

Lighting manager

Cor van den Brink

Props manager

Niko Groot

Costume supervisor

Claire Nicolas

Jojanneke Gremmen

First dresser

Jenny Henger

First make-up artist

Frauke Bockhorn

Sound technicians

Florian Jankowski

Timo Kurkikangas

Dramaturgy

Jasmijn van Wijnen

Surtitle director

Eveline Karssen

Surtitle operator

Jan Hemmers

Head of music library

Rudolf Weges

Set supervisor

Mark van Trigt

Production management

Maaike Ophuijsen

Chorus of Dutch National Opera

Sopranos

Lisette Bolle

Taylor Burgess

Jeanneke van Buul

Caroline Cartens

Melanie Greve

Simone van Lieshout

Tomoko Makuuchi

Sara Pegoraro

Jannelieke Schmidt

Altos

Elsa Barthas

Rut Codina Palacio

Yvonne Kok

Fang Fang Kong

Maria Kowan

Myra Kroese

Sophia Patsi

Marieke Reuten

Klarijn Verkaart

Tenors

Wim Jan van Deuveren

Milan Faas

Ruud Fiselier

John van Halteren

Stefan Kennedy

Raimonds Linajs

Frank Nieuwenkamp

Francois Soons

Bert Visser

Basses

Jorne van Bergeijk

Julian Hartman

Sander Heutinck

Richard Meijer

Maksym Nazarenko

Vincent Spoeltman

Rene Steur

Rob Wanders

Extras

Keerthi Basavarajaiah

Flory Curescu

Niels Gordijn

Niels van Heijningen

Evgenia Rubanova

Britt Scheltens

Bao Tieu

Nico Weggemans

Residentie Orkest

First violin

Lucian-Leonard Raiciof

Ilya Warenberg

Naomi Bach

Orges Caku

Yuki Hayakashi

Momoko Noguchi

Pieter Verschuijl

Francisca Portugal

Floortje Gerritsen

Giulio Greci

Daniel Perzhan

Gideon Nelissen

Belén Pérez Carreras

Myrte van Westerop

Second violin

Justyna Briefjes

Gerard Spronk

Barbara Krimmel

Ben Legebeke

Abel Rodriguez Garcia

Sergiy Starzhynskiy

Cato Went

David Pablo Bellido Herrero

Diederik Jan van Wassenaer

Yulia Gubaydulina

Lotte Reeskamp

Phoebe Tarleton

Viola

Timur Yakubov

Hannah Strijbos

Judith Wijzenbeek

Moira Bette

Elisabeth Runge

Jan Buizer

Tanja Trede

Iteke Wijbenga

Marieke de Jong

Michiel Wittink

Cello

Gideon den Herder

Iedje van Wees

Justa de Jong

Miriam Kirby

Tom van Lent

Sven Weyens

Julie-Anne Manning

Diana Sanz Pascual

Double bass

Frank Dolman

Jos Tieman

Astrid Schrijner

Reinout Hekel

Peter Luit

Bas Vliegenthart

Flute

Eline van Esch

Rieneke Brink

Dorine Schade

Oboe

Roger Cramers

Hilje van der Vliet

Vincent Wijk

Clarinet

Hans Colbers

Jasper Grijpink

Alfonso Saiz Revuelta

Bassoon

Gretha Tuls

Simon Vandenbroecke

Erik Reinders

Horn

Ron Schaaper

Elizabeth Chell

Mariëlle van Pruijssen

Mirjam Steinmann

Trumpet

Erwin ter Bogt

Robert-Jan Hoffman

Trombone

Timothy Dowling

Arno Schipdam

Wouter Iseger

Tuba

Elias Gustafsson

Timpani

Chris Leenders

Percussion

Martin Ansink

Murk Jiskoot

Joeke Hoekstra

Gerda Tuinstra

Harp

Mathilde Wauters

Piano

Sepp Grotenhuis

Celesta

Daan Kortekaas

Innocence in a nutshell

Innocence in het kort

Innocence in a nutshell

The composer: Kaija Saariaho

The oeuvre of the acclaimed Finnish composer Kaija Saariaho (1952-2023) stands out for the unique way in which she utilises the timbre and the density of sound. Her first opera, L’amour de loin, premiered in 2000. It was followed by Adriana Mater (2006), the monodrama Émilie (2010) and Only the Sound Remains (2016).

Whereas in previous operas Saariaho had shown herself to be a virtuoso in creating a lyrical, meditative musical atmosphere, her fifth and final opera Innocence (2021) marks a change in direction with a stronger narrative drive. The multilingual libretto, with nine different languages being spoken and sung, the relatively large cast of thirteen soloists and the exploration of various forms of expression in the human voice constituted a challenge that pushed Saariaho to produce an exceptionally rich, multi-faceted work. For example, in addition to classical singing, Innocence features Sprechgesang, traditional Finnish folk singing and highly rhythmical spoken texts.

The repercussions of a school shooting

Innocence revolves around the repercussions of a shooting at an international school. Why did the perpetrator do what he did? Could it have been prevented? And do his family, friends and classmates share some of the blame? In this opera full of suspense, Saariaho tackles a subject that is highly topical in Europe. In Finland, the country that both the composer Kaija Saariaho and the librettist Sofi Oksanen are from, the school shootings in Jokela (2007) and Kauhajoki (2008) are still fresh in people’s memory. Indeed, it is no coincidence that Innocence is set in Finland.

The libretto

The libretto for Innocence was written by the Finnish author Sofi Oksanen; she collaborated closely with the dramaturg Aleksi Barrière on this, her first opera libretto. The opera combines two timelines. On the one hand is the here and now, the day on which Tuomas marries Stela, who has no idea why there are so few guests at the wedding. On the other hand, there is the timeline of memory, with the victims of the shooting committed by Tuomas’ brother.

The staging

Director Simon Stone and set designer Chloe Lamford developed an innovative rotating set that brings the opera’s different timelines together. We see not only the restaurant where Stela and Tuomas are celebrating their wedding but also the school where the shooting took place ten years earlier. By playing with the design of these spaces — which range from incredibly realistic and true to life to disorientingly empty — the set adds an important layer to the visual expression of the tragedy that is at the heart of Innocence.

The story

Follow the link below to read the story of Innocence.

The story

The story of Innocence unfolds along two timelines. In one, a wedding takes place in Helsinki in the 2000s. In the other, in a world of memories, seven people look back at a tragedy that took place ten years earlier. Gradually, the connection between the present and the past is revealed.

Ten years after a cold-blooded shooting at a school, Stela is marrying Tuomas, the perpetrator’s brother. Stela knows nothing about the family’s horrific past, which is referred to as ‘The Tragedy’. Tuomas’ parents cannot agree on whether to tell her or not.

At the wedding, the waitress Tereza fills in for a colleague at the last minute and discovers to her shock that she knows the family: her daughter Markéta was one of the victims of the shooting. Tereza reveals all to Stela. Tuomas’ mother lays the blame on Markéta, who had joined others in bullying and humiliating the shooter.

Stela is prepared to accept everything out of love for Tuomas, but Tuomas sees his chance of starting all over again ruined for good. He confesses the truth — that he knew more about his brother’s plans than he ever let on.

Kaija Saariaho – A portrait

Dutch National Opera mourns the passing of Kaija Saariaho. Saariaho was one of the most influential composers of our time who made a crucial contribution to the development of contemporary opera through the intimate sound world of her music and her theatrical sensitivity.

Kaija Saariaho – A portrait

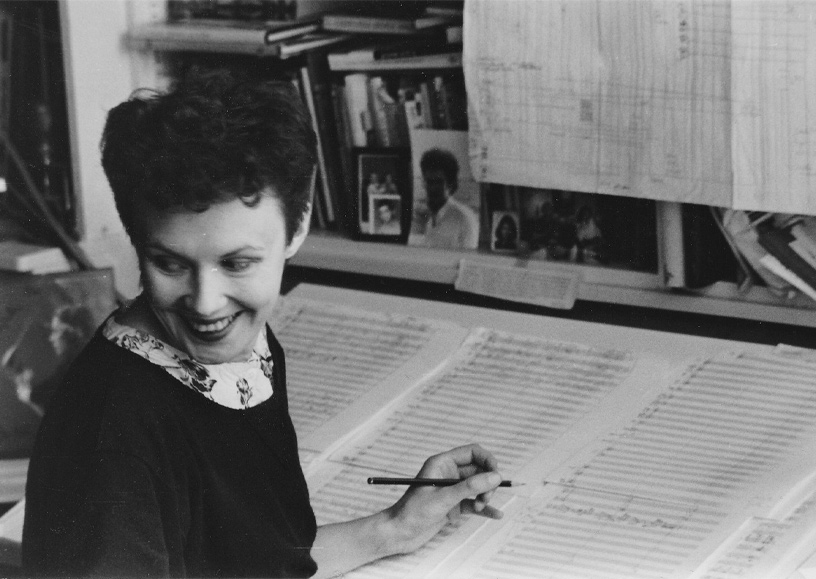

Kaija Saariaho (1952-2023)

Director Sophie de Lint: “With Innocence, Kaija Saariaho crafted one of her most haunting and poignant scores. We were eagerly anticipating her presence in Amsterdam for the Dutch premiere of this work and are deeply saddened by her passing. We will pay tribute to this exceptional composer and hope to honour her appropriately with the premiere of Innocence. Her musical genius will endure through this production and through her legacy.”

1952

On 14 October 1952, Kaija Saariaho is born as Kaija Laakkonen in Helsinki, Finland. (The surname Saariaho is from her first marriage.) As a child, she learns to play various musical instruments. She also starts composing at a young age. She loves the fine arts as well and she takes a course in graphical design. Her affinity with the visual arts will become evident later on in her compositions, in which she seems to be painting with sound.

1980

After completing her music course at the Sibelius Academy in Helsinki, Saariaho continues her training at Freiburg’s music academy and does summer courses in the modernist hub of Darmstadt. It is here that she encounters spectralism for the first time. Spectralism is a practice that takes the entire spectrum of sound from pure tones to white noise as the raw material and arrives at new compositional results by analysing the components of the sound.

1982

Saariaho moves to Paris to develop her skills further at the avant-garde Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique (IRCAM). Inspired by spectralism, she carries out computer analyses of the sound spectrum of individual notes produced by various instruments. She also develops techniques for computer-assisted composition, experiments with musique concrète – using recorded sound fragments as the raw material — and writes compositions that combine live performance with electronic sound.

1984-86

Verblendungen (1984, for orchestra and tape) and Lichtbogen (1986, for ensemble and electronics) are Saariaho’s first major successes. In both compositions, Saariaho mobilises dense sound, often at slow speeds, and lets the live instruments compete and interact with the electronic sound.

1994

In the course of the 1990s, Saariaho increasingly puts the human voice and instruments centre stage in her compositions. The violin concerto Graal théâtre (1994) is an early example of her mature idiom. Her focus is on evoking sparkling, slowly evolving soundscapes that resemble visual effects in their dreamy tendencies: light on water, the night sky — whether full of stars or pitch black — and the spectrum of colours.

2000

Saariaho’s first opera, L’amour de loin, premieres in Salzburg. The libretto is by Amin Maalouf, and Peter Sellars is in charge of the stage direction. With refined melodic lines and a lyrical warmth, Saariaho tells the story of the medieval troubadour Jaufré who dreams of an idealised love to escape the tedium and superficiality of his life. It is a drama of the inner self in line with Olivier Messiaen’s contemplative Saint François d'Assise, the opera that persuaded Saariaho it was possible to write an opera without narrative music.

2006

Adriana Mater, Saariaho’s second opera, premieres at the Opéra national de Paris. It is Saariaho’s second collaboration with Amin Maalouf (libretto) and Peter Sellars (stage direction). This work for four vocal soloists revolves around motherhood and violence during a civil war.

2010

In the monodrama Émilie (2010), written for the Finnish soprano Karita Mattila, Saariaho explores the inner turmoil of the eighteenth-century philosopher and mathematician Émilie du Châtelet during her pregnancy. Once again, the libretto is by Amin Maalouf.

2016

Only the Sound Remains, a two-part opera for countertenor and bass-baritone that was inspired by Ezra Pound’s translation of Japanese Noh dramas, has its world premiere at Dutch National Opera. Once again, Saariaho’s regular partner Peter Sellars is responsible for the direction.

2021

Innocence has its world premiere at the Festival d’Aix-en-Provence. Saariaho’s fifth opera is a fascinating new chapter in her oeuvre. The riveting libretto, with nine different languages being spoken and sung, the relatively large cast of thirteen soloists and the exploration of various forms of expression in the human voice constitute a challenge that pushes Saariaho to produce an exceptionally rich, multifaceted work.

2023

Kaija Saariaho dies from brain cancer on 2 June 2023 in Paris at the age of 70. Her final composition, the trumpet concert HUSH, premieres posthumously on 24 August 2023 at the Helsinki Festival.

Speaking in tongues

Follow the link below to read more about Innocence’s unique characteristics.

Verschillende talen en stijlen

Kaija Saariaho’s operas tend to occupy their own elusive worlds. Her first, L’amour de loin, stages an elliptical exchange between two characters marooned as far from one another as the twelfth-century setting seems to us. Only the Sound Remains hinges on the ingrained abstraction of the Japanese Noh tradition. Even Adriana Mater – once Saariaho’s most present, realist opera – unfurls its meditation on an unknown crisis in an unspecified place

Innocence changes all that. Here we are unequivocally in the composer’s native Finland, in the present day. The subject matter could hardly be closer to home. We meet characters like ourselves, suffering tangible traumas, exchanging facts and opinions, sometimes via plain speech. We see them, in Simon Stone’s production, among drab institutional furniture and under merciless strip lighting. They are surrounded by their own half-eaten snacks, their own strewn coats and bags.

When Innocence was first staged at Aix-en-Provence in the summer of 2021, those images took Saariaho by surprise. “It is not what I imagined,” the composer admitted. “At first I was worried about the technical elements – how the voices would work in all these different rooms. I had imagined all the characters together on stage all the time. But I never argue with stage directors, because it’s their job to make the staging just as it’s mine to make the music. And of course, Simon’s work is brilliant.”

Thirteen leading roles

Innocence’s sprawling cast list signals yet another break from Saariaho’s established modus operandi. Until now, her operas have focused on intense dramatic force fields anchored by two, three or perhaps four individuals. Here there are 13 principle stakeholders in a drama no less emotionally charged. The initial concept was for an opera titled Fresco. It would examine the seismic effects of a colossal tragic event on 13 individuals – the number of diners depicted in da Vinci’s mural The Last Supper, characters in whom Saariaho imagined ‘different lives, different secrets and different degrees of innocence’.

As the composer faced the near-impossible task of establishing 13 distinct personas in the medium of sung music, dramaturg and librettist Aleksi Barrière proposed an inspired dramatic solution: to use a cocktail of different languages and vocal techniques, including speaking and folk singing. “It opened my palette,” Saariaho explained, “and it meant we could use a bit more text, as speaking is so much quicker.”

Responsible for that text was the celebrated Finnish author Sofi Oksanen – an experienced playwright and novelist, but new to opera. “I thought Sofi’s way of dealing with trauma and different layers of time would be useful,” said Saariaho. With Barrière as a guiding dramaturge, the three arrived at a shortlist of three possible scenarios for the tragic event on which their opera would pivot. It was Oksanen who made the final choice: a shooting at an international school and the contrasting but convergent lives it shatters.

Only the victims are portrayed on stage. But are those we meet – survivors and relatives of the murderer – really so ‘innocent’? “No heinous crime can be perpetrated in the Nordic countries without some sense of collective soul-searching, born of the societal principle that if a land can produce a monster, all of its citizens are somehow culpable. ‘That is why we wanted the opera set in Finland,” says Saariaho; “we have had these sorts of things happen.”

Language

The composer took it upon herself to vicariously ‘live everything that these people are going through’ – to channel their individual and acutely challenging emotions, from which her calligraphic musical gestures might then emerge. Embedded in that process was the task of creating character identities based on language. What some critics interpreted as a shift in Saariaho’s aesthetic is rationalized by the composer as a natural exploration of contrasting linguistic qualities. “For decades now I have tried to understand why different languages call for different orchestrations, for example,” she said. “Some of it I do understand of course: some phonics are very distinct in different languages but still there is a kind of secret part that is fascinating.”

Setting multiple languages Saariaho doesn’t speak proved testing. “Aleksi arranged for natives to speak the words for me at different speeds, to give me an idea of the prose,” she explained. She made computer analyses of the words and examined their musical anatomy – not unlike the parallel exercise undertaken, via more analogue means, by the opera composer Leoš Janáček. “It was a crazy, long, complex composition process and one that I will never in my life return to,” exclaimed the composer, with as much despair as her demure disposition will allow.

Finno-Ugric folk music

One particular language cuts into the score for Innocence with particular potency. It is that of the character Markéta, sung by a specialist in singing techniques from Finno-Ugric folk music, Vilma Jää. Markéta stands apart from the rest of the cast for reasons that will become obvious. So does her fantastical music, using the distinctive voicebreaking techniques of the Viena Karelian ‘yoik’ – a herding call of the Sámi people indigenous to Finland’s northern reaches. Saariaho and Jää explored vocal techniques together. The composer recalls that she ‘heard myself, as a little girl, my grandmother calling cows on the field,’ when tailoring Markéta’s music to Jää’s voice.

The result of all this is a collage that doesn’t feel like a collage – threads of individual character, vocal style and language woven into the consistent and unifying fabric of Saariaho’s music. Her hallmarks remain steadfast: textures of extraordinary coloristic delicacy; lucid and cutting strings; decoratively lyrical wind and brass; and a chorus murmuring with unsettling atmospheric noise. Added to this is a new rawness, a new propensity to lash out, particularly from Saariaho’s orchestra.

Concentration

She used Berg’s Wozzeck and Strauss’s Elektra for guidance, but insists they were not ‘models’ in anything other than timing; Saariaho wanted her opera to clock in at under 100 minutes with no interval to diffuse the tension. As in Wozzeck, there is a sense of hopeless tragedy tugging at the score from the start of Innocence, even if some forty minutes pass before we know a single life has been lost (Wozzeck also has vernacular music slice into its score at moments of particular dramatic pertinence).

Unlike Elektra, whose orchestra rages and thrashes in psychological sympathy with the characters on stage, emotions are notably restrained in Innocence – until they can no longer be contained and split the entire ensemble momentarily open. “That comes partly from Sofi [Oksanen],” says Saariaho; “she does the same in her books: lets things out very gradually or with a sudden surprise.”

The composer describes the gun violence experienced recently in the Western world as ‘beyond belief’. She lives in Paris which witnessed the Bataclan massacre and identifies ‘strongly’ with those Nordic countries that have experienced shootings. Despite her opera’s reluctance to let anyone off the moral hook, she leads us into some sympathy with the victims.

Ultimately, she allows some of them the promise of hope. ‘There are ways to continue living after an event like this,’ says Saariaho; ‘not to forget, just to continue living. But perhaps those rays of sunshine are quite timid.’

Text: Andrew Mellor for The Royal Opera

Andrew Mellor is Copenhagen correspondent for Opera News, Associate Editor (Scandinavia) of Opera Now, and author of The Northern Silence – Journeys in Nordic Music and Culture (Yale University Press).

‘We feel an incredible empathy with each and every character’

Follow the link below to read the interview with conductor Elena Schwarz.

‘We feel an incredible empathy with each and every character’

Innocence is Kaija Saariaho’s most recent opera, and sadly her last. Elena Schwarz thinks it is one of the most harrowing operas of recent years. ‘This work has an astonishing ability to confront us with our deepest emotions and major moral dilemmas.’

Innocence is a new opera that most people will not know. How would you describe it?

“I think I would use two images. It feels to me like a mosaic with a lot of fine details, which are not only aesthetically pleasing in their own right but also combine to create a truly overwhelming effect. But a mosaic is perhaps too static an image for this powerful work. It also feels to me like a spiral that carries us with it, playing with our perception of time and reality.”

“We are sucked into an illusion, a situation that is gradually revealed to be very different from what we thought. I think audiences will feel guided through the opera, partly thanks to how subtly Saariaho has structured the music. The opera has so many layers for you to discover, with lots of surprises.”

According to Saariaho, the opera was inspired by Leonardo da Vinci’s fresco The Last Supper. What was she trying to say with that?

“Like the painting, the opera has thirteen characters. Someone looking at the painting without knowing the cultural associations will just see an ordinary supper. But there is this extra layer: each individual is in the grip of strong emotions and has their own hidden agenda, which we only discover gradually when we examine the painting more closely.”

“We come into the opera without any background information so it starts as a perfectly ordinary wedding party where people are toasting the bride and groom. But then that extra layer appears, and in its wake the shadows and complexities. I like that image; it genuinely helped me understand the work. It is a story that evokes strong images, which are supported by the score, the emotionally powerful music composed by Saariaho.”

How has Saariaho shaped the opera? What does she do musically to engage us with the story?

“Saariaho had a specific term for how she composed and created tension in her music: the timbral axis. That’s the idea of dissonance and darkness at one extreme and clarity and light at the other. She viewed her music through that lens, and I think if you listen to the opera with that fact in mind, you will experience it as oscillating between the darkness and the light. There are times when the music is very dissonant, as well as moments when she almost suggests tonality and where she plays with your sensations like in a watercolour, almost but not quite sounding a chord. You hear that in some of the choral passages, where just one voice deviates slightly from the rest.”

“It creates a whole range of possibilities in this opera, and Saariaho explores them all. In the prologue, you have the rather forceful polyphonic music for the orchestra and then at the end of the third act, you have a lone singer singing one falsetto note. The sound world of this opera is wide-ranging and interesting; the vocal parts include speech and lyrical singing as well as folk music. The music is raw and abrasive where necessary, but is also allowed to breathe in other places. It switches from highly complex to very pure, but invariably has so much clarity. And beauty.”

Are there certain musical accents that stand out in this opera?

“There are lots of lovely moments in the score for me. I’ve always loved Saariaho’s choral work and I think she does something quite special with the role of the Teacher. That character is almost always accompanied by the choir, which echoes and reinforces her experience. You have the feeling the entire room is resonating with this one person. Saariaho wrote the role specifically for Lucy Shelton using a kind of Sprechgesang, a mix of speaking and singing, which gives the music a really nice colour.”

“I also think the use of Finnish folk singing works very well, the traditional calls to the herd to get them to come home, sung in this opera by Vilma Jäa. In addition, I found Saariaho uses a trio of harp, celesta and piano, an amazing sound, to mark a shift in the timeline. That is definitely something to look out for; it creates an almost fairy-tale atmosphere at times.”

Innocence is a real ensemble piece with thirteen roles. How does Saariaho differentiate the characters?

“There are no insignificant roles in this opera. Saariaho has found a way to distinguish each character by using a musical language specific to them, for example, a harmony or a kind of leitmotif. She also has a unique approach — subtle and at the same time powerful — to combining them and connecting each character musically to one another and their surroundings. I find it very cinematographic the way the atmosphere switches, sometimes with blurred transitions.”

“Having so many different languages in one piece of music is quite unique. The nine languages serve as an additional tool for defining the singers and characters on stage. It feels completely organic and has a dramatic logic within the structure of the opera. Rather than creating distance, it actually brings us closer to the individual characters. There is only one brief passage where they all come together and all the students sing at the same time. That is the only moment when the languages collide with one another. To a certain extent, the opera reflects the complexity of our society in which we are constantly switching between all those different languages.”

What does Innocence mean for you personally?

“The opera is called Innocence but it really questions what that is, whether someone can ever truly be innocent. That moral question is the opera’s starting point. The opera tells the story of people who are wrestling with incredibly profound traumas. We see them trying to pick up their lives after a huge tragedy. We see the human side to everyone, which brings a little light into the narrative. That is explored beautifully in the music and the libretto, which fit together perfectly, moving from darkness and adversity to vulnerability. Each individual has moments, however brief, when we look into their soul, and those are the moments when I feel a real connection with them. It is very much a story for our times, one that portrays the issues we are struggling with in the here and now.”

This is the last opera Kaija Saariaho was able to complete before her death. How does it fit in her oeuvre as a whole?

“Many of the themes she had explored previously in earlier works come together in this opera. The different forms love can take, for example, and the inability to communicate with one another, and also the subject of violence and the repercussions of a hugely tragic event. Motherhood, another prominent theme in Saariaho’s work, is a key aspect here too.”

“It is an opera that combines so many different elements through the story and the amazing libretto. People who have never heard anything by Saariaho before will definitely enjoy Innocence, but people familiar with her work will hear so many echoes of previous operas and other compositions by her. In that sense, Innocence is a fantastic legacy.”

Text: Benjamin Rous

The absence of innocence

A conversation with stage director Simon Stone.

The absence of innocence

The mass shooting of innocent children and their teachers in schools is a crime so appalling that it seems to belong in the realm of nightmare rather than of real life. Yet in the United States, where the majority of shootings happen, there have been hundreds since the Columbine massacre in 1999, in which 12 students and a teacher died. Part of its particular horror is that the shooters (mostly, though not all, men) are more often than not part of the communities whose future they apparently set out to destroy.

Can there be a clearer marker of societal breakdown? Once the dead have been counted and the news crews have departed, a wound is left in the collective psyche which cries out to be cauterised. But how can this be achieved, when the violence is so random, the killer is often dead and therefore beyond justice, and the victims extend so far beyond the bodies on the floor?

School shootings in popular culture

Popular culture has long been transfixed by the apparent randomness of the crime and its dangerously alluring link to teenage alienation, ‘I don’t like Mondays,’ sang the Boomtown Rats in 1979, quoting the killer in the Cleveland Elementary School shooting in San Diego earlier that year. ‘You better run, better run outrun my gun,’ sang the American Indie band Foster the People in Pumped Up Kicks, an unexpectedly successful 2011 debut single about a neglected boy who finds power in his absent father’s six-shooter gun. Briefly banned from some US radio stations after the Sandy Hook Elementary School shootings in 2012, which resulted in 26 school deaths, Pumped Up Kicks exemplifies the queasy fascination of the subject: the song is a crowd-pleaser that has since been referenced in TV series ranging from Gossip Girl to Homeland.

Columbine brought filmmakers into the picture. In his 2002 documentary Bowling for Columbine Michael Moore investigated how and why it happened, attributing it to the lethal combination of inequality, fear and guns in America, where the right to bear arms is part of the foundational story. A year later, Gus Van Sant moved it into fiction with Elephant, a film about a shooting by two boys at a Portland, Oregon high school, that has had a profound effect on Innocence director Simon Stone.

‘I think Elephant is a guiding light for a lot of my generation. I saw it when I was 17 and it’s an absolute masterpiece. It fundamentally de-glorifies violence. It makes you fall in love with each person, each of the victims and makes you have to engage with the kind of normality of the perpetrators and how it could be you,’ he says.

The idea of a literally unspeakable atrocity, which begins and ends with the society on which it is visited, is the bedrock of Innocence. A family sits down to a feast celebrating the wedding of their beloved son. It is meant to be a fresh start, but the bride is an outsider who knows nothing about her fiancé’s background. How can a marriage succeed if it is founded on evasions? All it takes is one coincidence for the whole charade to be broken apart but – given that it is all taking place in a small community – is there even such a thing as coincidence?

‘Before’ and ‘after’

From this premise, the opera moves beyond the usual blood-soaked depiction of communal violence. Only in a single scene, when he is bullied by his schoolmates, is the killer given a face: the rest of the time he is a shadow. Though the terror and pathos of the shooting are devastatingly evoked by Kaija Saariaho’s music, we are only witnesses to the before and after of it.

This, says Stone, is the key to the production. ‘At some point in the story, there is a human who became a monster. I don’t give anyone an opportunity to identify with him, nor to feel like they’ve seen him. So it’s as if he is a projection all of our worst nightmares. I want the audience to be able to believe that that could be their child and that we are all, as a society, complicit in the creation of these people. I think that not glorifying a shooter is absolutely correct. But I also think that dehumanising them is to absolve ourselves of our responsibility.’

The multi-level, revolving stage allows this before and after to happen simultaneously, suggesting that a shooting is not just a case of one thing leading to another to another, but that at every stage, and on every level, there is both suffering and responsibility. Instead of ending with the assertion that the dead should never be forgotten and can never forgive, Innocence boldly reframes what constitutes catharsis, that surge of emotional release which has been part of a story-telling tradition that goes back to the ancient Greeks.

We are accustomed to seeing evil avenged and wrong-doers punished, even if – like Medea or Othello – their wrong-doings are the result of monstrous injustices. Tragedy exists to let us off the hook. They bleed, we weep, and then we all go home purged. ‘The difference here,’ says Stone, ‘is that there is a distance in terms of time; it’s something that people should have been able to move on from, but so much has been left undiscussed and unresolved. So it’s in some ways an active exorcism for all of the characters.’

What makes a monster?

In her 2003 novel We Need to Talk about Kevin, Lionel Shriver posed the question: what makes a monster? Is it nature or nurture? For in the mind of his distraught mother, through whose eyes the story is viewed, Kevin is indeed a monster, though that doesn’t prevent her from agonising as to whether some personal failing or disastrous misjudgement of her own might have set her son on the course to his murderous rampage.

It is not coincidental that two of the most vivid antagonists of Innocence are also mothers: one is haunted by her dead daughter, and the other has been frozen into a rictus of denial by the deeds of her murderous son. The wedding at which they meet should be ushering in a happy future, but cannot do so until the ghosts of the community to which both belong are laid to rest.

Part of the horror, says Stone, ‘is finding out that your child was not only capable of doing something terrible, but also that they’d been planning it and becoming increasingly capable of it under your watch, and the level of complicity that puts on you. The parents all think their children are innocent, but there is a moment when children graduate from being essentially innocent to being adults before their time. What’s beautiful about the piece is several of the student population also admit their own deeply flawed personalities, so it’s about everyone discovering how quickly what can seem like harmless school playground politics can tap into a real adult trauma.’

Reconciliation with the truth

The catharsis of Innocence, then, is not about violence and retribution but about the power of reconciliation with the truth. School shootings, it suggests, are not about one shooter and a load of victims. Nor, the multilingual presentation insists, are they the problem of any single culture. Nobody is innocent, everyone is implicated. Without honesty, there can be no forgiveness, and without forgiveness, there can be no peace. With a loving will, all these things may one day come to pass.

Text: Claire Armitstead for The Royal Opera

On the other side of violence

Dramaturge and translator Aleksi Barrière looks back on the making of Innocence.

On the other side of violence

In the spring of 2013, Kaija Saariaho invited Sofi Oksanen and me to dinner. She had received a proposal from the Royal Opera House to write an opera inspired by the contemporary world, and was excited to compose, for the first time, a work for the stage that she envisioned would contain numerous characters, languages and perspectives on the same event. Kaija called the project Fresco.

For this, she needed a virtuoso storyteller who could approach the complexity of our world through carefully crafted characters: Sofi. A dramaturge and translator familiar with opera was also needed because Sofi would be writing her first opera libretto, and she would do so in Finnish, whereas the final work would be multilingual. This was how I ended up at this first dinner, trying to answer Sofi’s first question: what subject has not yet been dealt with in an opera?

Of course, this question was about more than the allure of novelty. Operas have been written about the full range of human experience: love, jealousy, ambition, gods, tyrants, murderers, rapists, slaves, rebels. To what contemporary phenomenon could we apply the tools of opera to expand our understanding of the ways human beings cause and feel pain, and survive?

Possible topics

Three artists, three generations, three forms of expression. During our discussions, we let the list of possible topics grow. Sofi recently published her novel When the Doves Disappeared (2012), in which Estonian characters survive the Second World War and changes in government by fighting or adapting, lying to others and to themselves. Kaija was composing an opera based on a Noh play about a soldier whose traumatized ghost demands a ritual from the living to finally find peace (Only the Sound Remains, 2016). I had just directed a performance of the Kindertotenlieder, setting Mahler’s songs on the death of children in the aftermath of the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting, and focused on the grieving of the parents (Tu ne dois pas garder la nuit en toi, 2013). Fresco was something completely different from our other projects at the time, we thought. However, the questions troubling each of us were engaging in a secret conversation like the roots of trees underground. As our discussions progressed, Sofi worked on an original story about the revelation of a hidden crime from the past at a family party; she called it The Uninvited Guest.

Wedding pictures

Kaija had come up with a formal idea for a group fresco, in the style of Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper, and Sofi had drawn an association between that image and wedding photos, where solemn faces conceal hidden family dramas. The structure she built is similar to many of her novels: the interaction of two intertwining timelines, or narrative levels, sets off a series of revelations and gradually enriches our understanding of the characters. The implementation of this arc in this new work is, perhaps partly due to the density of the libretto form, one of Sofi’s most refined achievements as an author.

The characters grew as my translations were completed and started circulating between the three of us via e-mail in the summer of 2016. Sofi polished the text and Kaija used recordings of the translations to develop a melodic and harmonic language for each character, from which the rest of the opera’s music grew. Our decision to give certain roles to actors instead of singers enabled both a larger use of text and new ways for Kaija to weave it into the music.

Individual and connected

The work was no longer just Fresco, an abstract polyphonic form, and not simply The Uninvited Guest, the dilemma of an individual in relation to a group. We were giving birth to Innocence, a drama of thirteen people’s guilt and selfrecrimination; each the isolated prisoner of their own trauma, yet simultaneously bound through shared trauma.

In the same way, languages isolate people as much as they bring them together. In Innocence, the multiple languages coil the text and music together into an exploration of the layered desolation of our world.

When the work was rehearsed for the first time in the summer of 2020, amidst pandemic restrictions, it proved to be as important as it was challenging to build an opera that, by its very nature, required artists of different languages and disciplines to come together and create something in common. Beyond the message, the medium is a method.

‘Unexplained tragedy’

So how did this answer Sofi’s original question of addressing a new topic with the tools of opera and language? Sofi developed a wonderful answer with her libretto. She used the example of a school shooting and an abundance of roles to show how multifaceted and utterly structural the creation of violence is. A bloody act committed by a young person is always considered, as the libretto recalls, an ‘inexplicable’ ‘tragedy’. Sofi’s text evokes the superficial public debate that occurred following the Columbine, Dunblane, Kauhajoki, or Alphen aan den Rijn shootings: plenty of talk about youth violence, about the graphic nature of film and video games, and sometimes about the availability of guns. These are factors we could and should address better as a society.

However, broader questions remain taboos. These taboos arise from our rigid understanding of what falls under individual responsibility, from problems we fail to see as societal – such as mental health – and from the silent violence produced by workplaces, families and communities. Innocence considers how problematic our choices can be if we do not examine our own values and motives, and if we cling vehemently to convenient roles and narratives. Through its thirteen character arcs on loneliness and connection, the opera reminds us of the importance of bringing hidden stories to light, into public discourse: giving visibility to all narratives and to their interplay.

Eliminating physical violence

Only in a multilingual musical work for the stage is it possible to polyphonically weave together so many stories and interactions. However, artistic expression not only has a responsibility to present public narratives and our struggles with them; it must reflect on how they should be presented. As studies have shown, school shooters often revel in images created by the film industry on the topic, just as members of the military enjoy watching and quoting scenes from war films, even those that take a pacifist stance. How, then, can art avoid tolerating, normalizing or even encouraging violence while simultaneously depicting it? In the development phase of Innocence, the earliest and perhaps most radical decision we made was to exclude all physical violence – the shooting, and even the shooter himself – from the text and music, spotlighting, instead, the stories and voices that receive less visibility in a society enamoured with spectacle. In focusing on slower timelines of grieving and healing, Kaija’s music embraces the psychological reality of memory, trauma, repression and acceptance. Associative dream-state logic becomes more truthful and also more engaging than the thrill of pseudorealistic spectacle.

Alongside choreographer Arco Renz, director Simon Stone has developed a beautiful way of centralizing trauma, and giving it physical reality. As a skilled creator of images, Simon has also tried to tease the viewer’s expectations of visible violence, and part of his process has been to carefully dose the physical violence and appearance of the shooter. It would be interesting to see a production in the future that fully adopts the distinguishing principle of the text and music, and completely rejects the macabre fascination with violence that the mass media has cultivated in us. As an art form, theatre has an obligation not only to critique mainstream images but also to develop new images that are lacking in the homogenized public space. This opera is an invitation and a tool in that direction.

For its creators, it has been a continuation of our previous work and its climax. Above all, we hope it will inspire others to give visibility to the missing narratives we need, and encourage many difficult and necessary conversations.

Text: Aleksi Barrière

Instinctive atmosphere

Follow the link below to read the interview with set designer Chloe Lamford.

Instinctive atmosphere

In 2018, stage designer Chloe Lamford and director Simon Stone began to conceive of Innocence, their second collaboration together. What emerged was a design not only technically rich – full of literal twists and turns – but also an atmosphere that perfectly conjures the opera’s themes of memory, trauma and loss. Here, Lamford shares her sketches and references – from the work of Finnish architect Alvar Aalto to Edward Yang’s Yi Yi (2000) and Lars von Trier’s Melancholia (2011) – and looks back on her time creating an architecture whose layered collaging is emblematic of her characteristic versatility as a designer.

What was the process of designing Innocence?

“Working with Simon is particularly interesting because he creates spaces that are very theatrical, but they also have a real sense of place. So although the set is revolving and open to the audience, all of the interiors also have substance and a sense of reality. That’s the really exciting thing about working with him. The architecture is innately theatrical in terms of how it functions and feels really atmospheric.

Our process was examining architecture, and finding the right emotional space for this building that could move seemingly seamlessly between the restaurant action and memory space of the school, and that we could collage and create an architecture that could be all those things – that could be memory space and could be reality, and could be a space of loss and trauma. It was about researching and layering and finding all these different architectural and filmic references to build the right atmosphere.”

Were there challenges in trying to reconcile the present-day restaurant-wedding action with the memory space?

“The challenge was to create a space that could hold – because the opera jumps between these two realities – the reality of 10 years since the tragedy and then the reality of the incident itself. Simon’s amazing idea was that it’s the same building. So for me, it was really plotting through how each space could live against each other. It was a lot of working out how to do things secretly away from the audience so that you’re, as an audience, always experiencing its source of magic.”

When you approach projects, what do you look at for visual references?

“I look at film, I look at installations, I look at a lot of photographers. I really like to look outside of theatre and opera. Especially when your space needs to feel really real, or have a sense of reality.”

You’ve cited Alvar Aalto as a reference. Are you and Simon fans of his? And given that the opera is set in Finland, did Aalto’s Finnish roots have any impact?

“We’re definitely both big fans of modernist architecture and those stripped-back but beautifully proportioned spaces and buildings. To me as well, the sparsity and elegance of those slender lines and the way things are balanced were a huge influence. Because, in my head, the rooms with the sparsest of detail create a real sense of place and are quite atmospheric. When you put a figure into a space that’s very clean like that, you’re not reading acres of information, you’re reading specific information.

Aalto is so influential, he does crop up in lots of [other] design references, but because he’s Finnish it’s incredibly interesting and evocative here.”

What lies beneath this simple, clean elegance? Can something else be communicated?

“We created a space that looks very simple and beautiful. But you know, it can be both a restaurant and a school. So when you take away the restaurant, we’ve painted grubby little stains into the walls and the floor and it’s got this kind of heavy usage attached to it. It’s so clean, but then when you layer this history onto it, this history of pain – it’s sort of like how you might place a crisps packet in an empty canteen – suddenly you’re seeing everything really sharply against it. And that feels really aesthetically satisfying and really strong.

I mean, the restaurant itself isn’t the most beautiful restaurant either. It’s got a slightly rundown feel with the combination of event chairs and strange sort of chinoiserie panels and dingy lighting. It’s deliberately not the most luxurious space. That event furniture thing, that was a reference to Melancholia.”

Melancholia takes a lavish wedding setting but turns it somewhat dark, and tired. Did this resonate with you?

“Yeah, it's a little depressing, let’s say. And that felt right as a kind of base layer for the wedding. There’s this hidden secret to the family that gets revealed. And during the opera, as we start to discover the story, it felt right that the setting wasn’t all wonderful and happy. We referenced various films. In Yi Yi, they have these amazing, heart-shaped balloons that we really fell in love with. Like they’re trying very hard to be joyful, but it all comes across as quite sad.”

Smaller details like these can make a space feel more authentic. Can you speak more on the school notice boards you designed?

“We looked at a lot of imagery of schools. I mean, we’ve all pretty much been to school. Actually, at the Finnish National Opera, the props department helped us find posters from schools that have the right text on them and the right messaging. They helped us with food in the restaurant and food labels.”

What about the furniture? Was the make and material also modelled on Aalto and modern design?

“I think it definitely influenced us a lot. The school furniture is all modern, but it’s also minimal. I was looking for things that worked within those spaces, but it’s modern furniture.”

What was it like combining the architecture with the music?

“I’m really fascinated with making atmosphere. It’s definitely something that I do in my work, and try to do quite instinctively. You know, when layers feel right in relation to the libretto. But of course, because it was a new opera, we didn’t have the music. So it was really fascinating. We had snippets and little sections, which were very stimulating. And then we had the libretto. So we really created the design from this visual instinct.”

When it all came together, was it what you imagined it would be?

“It’s probably better, I think, because for me, the opera is just so incredible, and so evocative. I hope that the space and the music really talk to each other. That’s always my aim, that the two feel like they come from the same place. It’s kind of a sense of collaging. Multiple architectural spaces talking to each other and having the right conversation. Innocence is quite special in that respect.”

“There is just one more thing to say, actually, about the atmosphere of the piece. We create this restaurant space that is within the building that rotates, and we build school spaces. But we also take everything away, and it becomes an absence of things. It becomes this really strange empty memory space, where the wounds of a character are laid bare and exposed and confronted. The sparseness becomes so much. And you see so clearly a person’s pain within an empty room, and that felt quite key as well. It’s like revisiting the trauma and the emptiness. It’s very potent, and that was something we discovered in the making of the piece. That this kind of absence felt right.”

Text: Eloise Giegerich for The Royal Opera

Programmaboek

BECOME A FRIEND OF DUTCH NATIONAL OPERA

Friends of Dutch National Opera support the singers and creators of our company. That friendship is indispensable to them, and we are happy to do something in return. For Opera Friends, we organise exclusive activities behind the scenes and online. You will receive our Friends magazine and have priority in ticket sales.