La traviata

Performance information

Voorstellingsinformatie

Performance information

La traviata

Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901)

Duration

2 hours and 40 minutes, including one intermission

This performance is sung in Italian, with surtitles provided in Dutch and English

Opera in three acts

Makers

Libretto

Francesco Maria Piave

Musical direction

Andrea Battistoni

Stage direction

Tatjana Gürbaca

Set design

Henrik Ahr

Costume design

Barbara Drosihn

Lighting design

Stefan Bolliger

Dramaturgy

Bettina Auer

Revival direction

Meisje Barbara Hummel

Cast

Violetta Valéry

Adela Zaharia

Flora Bervoix

Martina Myskohlid*

Annina

Inna Demenkova

Alfredo Germont

Bogdan Volkov (27 and 31 Jan, 3 and 6 Feb)

Liparit Avetisyan (9, 12, 15, 18 Feb)

Giorgio Germont

George Petean

Gastone

Salvador Villanueva*

Barone Douphol

Roger Smeets

Marchese d’Obigny

Michael Wilmering

Dottore Grenvil

Bart Driessen

Giuseppe, servo di Violetta

Dimo Georgiev

Domestico di Flora

Sander Heutinck

Commissionario

Christiaan Peters

* Dutch National Opera Studio

Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra

Chorus of Dutch National Opera

Chorus master

Edward Ananian-Cooper

Original production by Den Norske Opera, Oslo

Production team

Assistant conductor

Aldert Vermeulen

Assistant director

Nico Weggemans

Assistant director during performances

Meisje Barbara Hummel

Directing intern

Robyn Terpstra

Rehearsal pianists

Peter Lockwood

Fabio Cerroni

Amy Chang

Daniel Ruiz de Cenzano Caballero

Language coach

Fabio Cerroni

Assistant chorus master

Ad Broeksteeg

Language coach chorus

Valentina di Taranto

Stage managers

Pieter Heebink

Emma Eberlijn

Sanne van Loenen

Artistic planning

Emma Becker

Costume production assistant

Lars Willhausen

Master carpenter

Wim Kuijper

Lighting manager

Coen van der Hoeven

Props master

Hanna Tynkkynen

First dresser

Jenny Henger

First make-up artist

Isabel Ahn

Head of Music Library

Rudolf Weges

Surtitle director

Eveline Karssen

Surtitle operator

Irina Trajkovska

Dramaturgy

Laura Roling

Set supervisor

Sieger Kotterer

Production management

Emiel Rietvelt

Chorus of Dutch National Opera

Sopranos

Aliya Akhmadeeva

Lisette Bolle

Else-Linde Buitenhuis

Jeanneke van Buul

Caroline Cartens

Nicole Fiselier

Kitty de Geus

Melanie Greve

Oleksandra Lenyshyn

Simone van Lieshout

Tomoko Makuuchi

Vesna Miletic

Sara Pegoraro

Jannelieke Schmidt

Claudia Wijers

Altos

Maaike Bakker

Elsa Barthas

Daniella Buijck

Rut Codina Palacio

Johanna Dur

Valerie Friesen

Yvonne Kok

Carlijn Kooijmans

Maria Kowan

Liesbeth van der Loop

Itzel Medicigo

Sophia Patsi

Marieke Reuten

Klarijn Verkaart

Ruth Willemse

Tenors

Thomas de Bruijn

Wim-Jan van Deuveren

Frank Engel

Milan Faas

Dimo Georgiev

John van Halteren

Stefan Kennedy

Robert Kops

Roy Mahendratha

Tigran Matinyan

Frank Nieuwenkamp

Richard Prada

François Soons

Julien Traniello

Bert Visser

Basses

Ronald Aijtink

Nicolas Clemens

Jeroen van Glabbeek

Julian Hartman

Hans Pieter Herman

Sander Heutinck

Dominic Kraemer

Matthijs Mesdag

Maksym Nazarenko

Christiaan Peters

Matthijs Schelvis

Jaap Sletterink

René Steur

Harry Teeuwen

Rob Wanders

Extras

Keerthi Basavarajaiah

Renato Bertolino

Andrea James Child

Creso Euclydes

Yannick Jhones

Mario Krastev

Judy Lijdsman

Alexey Shkolnik

Rob Winters

Manon Wittebol

Child extras

Ruza Haalmeijer

Mimi Maan

Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra

First violin

Ionel Manciu

Hed Yaron Meyerson

Saskia Otto

Arno Bons

Mireille van der Wart

Rachel Browne

Maria Dingjan

Marie-José Schrijner

Noëmi Bodden

Petra Visser

Annerien Stuker

Ilka van der Plas

Julie Adelsteinsonn

Second violin

Charlotte Potgieter

Cecilia Ziano

Laurens van Vliet

Tomoko Hara

Elina Hirvilammi-Staphorsius

Jun Yi Dou

Bob Bruyn

Eefje Habraken

Wim Ruitenbeek

Babette van den Berg

Melanie Broers

Lana Trimmer

Viola

Anne Huser

Galahad Samson

Kerstin Bonk

Francis Saunders

Veronika Lénártová

Leon van den Berg

Olfje van der Klein

Jan Navarro

Cello

Eugene Lifschitz

Joanna Pachucka

Daniel Petrovitsch

Mario Rio

Eelco Beinema

Pepijn Meeuws

Yi-Ting Fang

Double bass

Ying Lai Green

Jonathan Focquaert

Harke Wiersma

Arjen Leendertz

Ricardo Xambre Neto

Flute

Juliette Hurel

Beatriz Da Silva Baiao

Oboe

Remco de Vries

Ron Tijhuis

Clarinet

Julien Hervé

Romke-Jan Wijmenga

Bassoon

Lola Descours

Marianne Prommel

Horn

David Fernandez Alonso

Wendy Leliveld

Richard Speetjens

Pierre Buizer

Trumpet

Alex Elia

Jos Verspagen

Trombone

Alexander Verbeek

Remko de Jager

Rommert Groenhof

Tuba

Hendrik-Jan Renes

Timpani

Danny van de Wal

Percussion

Ronald Ent

Martijn Boom

Harp

Charlotte Sprenkels

In a nutshell

In het kort

In a nutshell

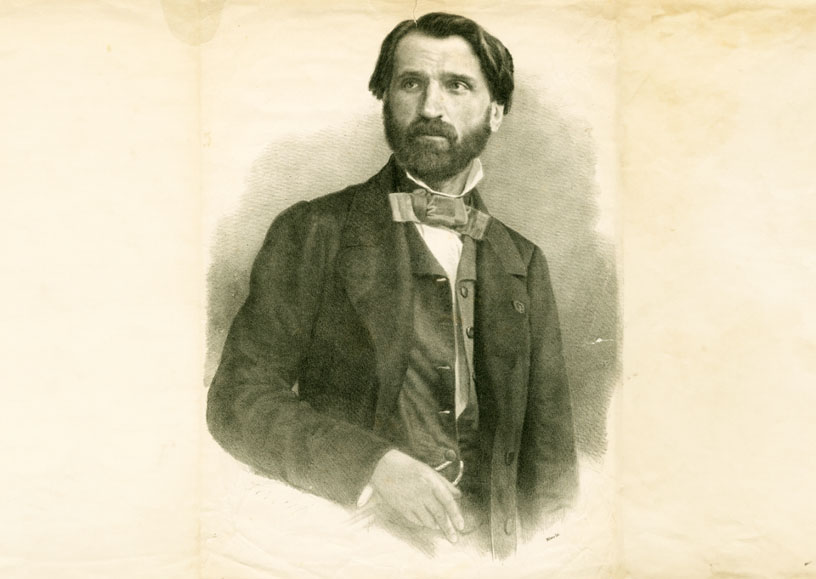

Giuseppe Verdi

Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) is one of the most important Italian composers in the history of opera. He had his international breakthrough in 1842 with Nabucco, which was followed by a highly productive period, culminating in the successful triad of Rigo- letto (1852), Il Trovatore (1853) and La Traviata (1853). In later life, Verdi continued to compose highly successful operas, including Aida (1871), Otello (1887) and his swan song Falstaff (1893). Throughout his long career, Verdi kept renewing and developing his musical-dramatic language.

Different faces of Violetta

Giuseppe Verdi and his librettist Francesco Maria Piave based their La Traviata (1853), on La dame aux Camélias (1848), a novel and play by Alexandre Dumas fils. La dame aux Camélias tells the story of the doomed love affair between courtesan Marguerite Gautier and her bourgeois lover Armand Duval. Dumas had modelled the character of Marguerite after Marie Duplessis, a Parisian courtesan with whom he himself had had a brief affair. Duplessis had died of tuberculosis in 1847, the year before Dumas’ novel appeared, at the age of only 23. Incidentally, the historical Duplessis never tried to escape her life as a courtesan; that was Dumas’ invention.

Contemporary opera

With La Traviata, Verdi wanted nothing more than to create a contemporary opera about his own time, rather than a distant past. Musically, we see this in the large-scale use of the waltz rhythm in the opera. Waltz music was extremely popular and ubiquitous in the salons and parties at the time. Verdi also wanted the sets and costumes to be completely contemporary, so that the audience would also physically see themselves reflected on the stage. The composer, who had experienced issues with censorship before, however had to give in: the setting of the opera had to be changed to the 18th century in order to make it more palatable for audiences. Never in his lifetime would Verdi get to see La Traviata in contemporary costumes.

“There is no art in turning a goddess into a witch, a virgin into a whore, but the opposite operation, to give dignity to what has been scorned, to make the degraded desirable, that calls for art or for character.”

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Tatjana Gürbaca

Director Tatjana Gürbaca originally created this production of La Traviata in 2015 for Den Norske Opera in Oslo. In 2021, when Dutch National Opera brought the production to Amsterdam, Gürbaca was present throughout the rehearsal period to revise her production with fresh insights. In her staging, Gürbaca makes the coldness and cruelty of the Parisian community, which runs on money and unbridled consumerism, particularly visible.

Set and chorus

The set designed by Henrik Ahr is highly minimalistic. The action takes place on and around a wooden platform that gradually comes apart in the course of the performance. There are no walls or other objects providing the performers with a point of reference. A key reason for this is the prominent role played by the chorus in this production. The chorus are present not just in the party scenes, where they have a singing part, but also at other times, serving in a sense as a backdrop in their own right.

“You know that we are living in a material world, and I am a material girl…”

Madonna

The story

Het verhaal

The story

The terminally ill courtesan Violetta Valéry is the most desirable woman in Paris. The parties she throws are the hottest in town and men are willing to spend large amounts of money for just a piece of her. Not so Alfredo Germont: what he has to offer and asks of Violetta is something immateria— love.

At first, Violetta is sceptical: she cannot imagine living any other life. Faced with the short time she has left to live, however, she decides to take the plunge. Together with Alfredo, she retreats to the countryside, far away from Parisian society, in a bid to start life afresh.

This proves impossible when Giorgio Germont, Alfredo’s father, pays Violetta a visit. His daughter’s marriage and respectability are in danger, now his son has brought shame on the family by living with a courtesan. He appeals to her to break off the relationship in order to save his daughter. For the sake of the young girl, Violetta makes the extremely painful decision to end her relationship with Alfredo.

Back in Paris, it proves impossible for her to pick up where she left off. She can no longer find her place in a world where she was once completely at home. On her deathbed, she hopes, against her better judgement, that the love of Alfredo can still save her.

Timeline

Tijdlijn

Timelin

1813

Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi is born on 10 October 1813 to a family of modest means in Le Roncole, a village in the Duchy of Parma. He first shows signs of his musical talent playing the organ as a child in the local village church. After completing secondary school in Busseto, Verdi continues his musical education with a scholarship to the conservatoire in Milan.

1824

On 15 January 1824, Alphonsine Plessis is born in Nonant-le-Pin, a hamlet in Normandy. At the age of fifteen, she moves to Paris where she finds work in a clothes shop. She soon discovers men are willing to pay for sexual favours. In no time she learns to read and write, and to converse elegantly, changing her name to Marie Duplessis and becoming the most sought-after courtesan in Paris. Her soirées in her salon are attended by all the leading men in Parisian society and she has relationships with various prominent figures.

1842

After suffering various blows — he loses his wife and two children in the space of two years — Verdi achieves success with his first operatic hit, Nabucodonosor (Nabucco). The main female role, Abigaille, is sung by Giuseppina Strepponi, who at the age of 27 has already had a tumultuous life. Not only has she built up a successful career as a singer, she has also given birth to three illegitimate children by different fathers, giving the babies up for adoption.

1847

On 3 February 1847, Marie Duplessis dies of tuberculosis. She is only 23 years old.

1848

Verdi and Giuseppina Strepponi, who became a couple in Paris the previous year, buy a country estate close to Busseto. Their relationship meets with disapproval in Italy, not just because of the aura of scandal surrounding Strepponi but also because they live together for twelve years before marrying.

1848

Alexandre Dumas fils, who had a brief affair with Marie Duplessis, draws on his personal experiences for his novel La dame aux Camélias. The novel tells the tragic love story of the courtesan Marguerite Gautier, who suffers from tuberculosis, and her admirer Armand Duval. Marguerite renounces her life as a courtesan for Armand and the couple retire to a home in the countryside. However, Armand’s father persuades Marguerite to break off the relationship with Armand because he fears it will damage the marriage prospects of his innocent youngest daughter. Marguerite spends the final days of her life alone and in misery.

1852

The stage adaptation of La dame aux Camélias, also by Alexandre Dumas fils, premieres on 2 February 1852 in the Théâtre du Vaudeville in Paris. The play is a huge international hit.

1 January 1853

On New Year’s Day, Verdi writes to his good friend Cesare de Sanctis: “I’m working on La dame aux Camélias for Venice; we are probably going to call it La traviata. A contemporary subject! No other composer would dare tackle it because of the costumes, the period and a thousand other scruples. But I’m thoroughly enjoying working on it.” Little did Verdi know then that he would never see a performance of La traviata in a contemporary setting in his lifetime: that was deemed too controversial and the opera was routinely performed in eighteenth-century costume.

6 March 1853

La traviata has its premiere in Teatro La Fenice in Venice. Much against Verdi’s wishes, the role of Violetta Valéry is played by the sturdy soprano Fanny Salvini-Donatelli. The day after the premiere, he sends a short letter to his friend Emanuele Muzio. “La traviata was a fiasco; is that my fault or the singers’ fault? Only time will tell.”

6 May 1854

After some minor changes, La traviata is performed again in Venice, this time in the Teatro San Benedetto. This second production is an overwhelming success. La traviata soon conquers the world and has been part of the standard operatic repertoire ever since.

1886

The first performance of La traviata in the Netherlands takes place on 11 September 1886, in the Théâtre Royal Français de la Haye (now the Koninklijke Schouwburg) in The Hague. The opera is sung in French.

1968-2021

The Traviata directed by Tatjana Gürbaca, which premieres on 4 December 2021, is the fifth production of La traviata performed by Dutch National Opera since the company was founded in 1965. The previous productions were by Jean-Marc Landier (1968), Tito Capobianco (1974, returning in 1978 and 1984), Alfred Kirchner (1993) and Willy Decker (2009, returning in 2013).

‘Verdi’s genius is in how he deploys simple means’

Interview with the conductor Andrea Battistoni

‘Verdi’s genius is in how he deploys simple means’

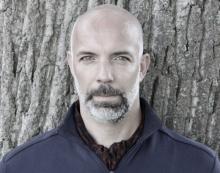

Interview with conductor Andrea Battistoni

As an Italian, Battistoni grew up with Verdi’s music. “The music from operas such as Rigoletto, Il trovatore and La traviata have been in my system from a young age.” But that isn’t necessarily an advantage: “Overfamiliarity with the music has its pitfalls. That’s why I still always go back to the score and examine it afresh. It’s not because I want to stick literally to what is written on the page — my aim is not to perform a work come scritto — but because that lets me find a faithful interpretation. Indeed, alert listeners will hear the occasional acuti (high notes) and puntature (minor changes made to help singers with tricky passages) that are not found in the score.”

Simple means with maximum effect

What fascinates Battistoni about Verdi’s music is the sophisticated simplicity. “At first sight, La traviata seems rather a basic, straightforward opera. Harmonically, it is quite simple and conventional. But what makes Verdi exceptional is how effectively he deploys such simple means.”

“La traviata makes extensive use of the waltz rhythm, a triple time signature, on a scale that is unique in Italian opera. Sometimes it is waltz music the characters themselves are hearing, for example in Violetta’s salon and in the famous ‘Brindisi’. At other times the waltz rhythm functions more as a memory, a window on Violetta’s state of mind and the impossibility of ever truly erasing the past.”

According to Battistoni, Verdi had good reasons for choosing the waltz for this particular opera. “Verdi wanted to make an opera about the times he lived in. And what was the most popular music in his day? Exactly: the waltz.”

Battistoni also sees the composer’s genius at work in the overture. “The overture starts with just a few violins playing a very simple melodic arc. This is actually a kind of flash-forward because the melody only reappears in the third and final act when Violetta is dying. In other words, the opening bars already contain a premonition of the inevitable end. But you already hear hints of the love affair in the overture too, with the love theme that Violetta sings in the ‘Amami, Alfredo’ in the second act. This lets Verdi convey the inextricable link between love and death in this opera from the start.”

Film director

In Battistoni’s opinion, Verdi’s dramatic skills are particularly on show in the first act. “Verdi’s approach is almost like that of a film director. He points his camera at different characters, conversations and situations, then skilfully assembles these elements to create a cohesive whole. There are the major chorus passages that express the feverish nature of the party, interspersed with snatches of conversation between the partygoers. That’s all followed by the music played by a small orchestra backstage. And against this backdrop of frivolous festivities, Violetta and Alfredo have a deep and meaningful conversation. Then you have an intimate love duet, after which the chorus comes in at full volume. The act ends with Violetta’s wonderful closing aria, in which you also hear Alfredo’s voice in the distance. You don’t know whether he is really standing below her window serenading her or whether this sound is purely in Violetta’s mind. The audience has to process a dense narrative with a lot happening in quick succession in this act, but you don’t miss anything because Verdi’s ability to tell a story is unparalleled.”

Three Violettas

It is sometimes said that the role of Violetta Valéry requires three sopranos, one for each act. There is definitely an element of truth in this, thinks Battistoni. “The first act requires a flexible voice for the coloratura, which underlines Violetta’s frivolity and her attitude to life at that point. In contrast, the role becomes highly lyrical in the second act and even turns quite dramatic in the final act. You need to be a vocally versatile singer in order to sing well in all three acts. But the role is equally challenging in terms of acting. The singer needs to have the kind of stage presence and acting skills that captivate the audience and keep her at the centre of attention at all times. The opera revolves around Violetta and the singer needs to be able to carry that off. There are good reasons why Violetta is known as a diva role.”

Conventional voices

The situation is different with Alfredo and his father, Giorgio Germont, says Battistoni. “Verdi reserved his most modern, revolutionary music for Violetta. Musically, Alfredo and Germont are much more conventional, in line with what Verdi was writing for such voices at this point in his career. We know Verdi loved the baritone voice and he often wrote incredibly melodic parts for it. That is absolutely the case for the father. Alfredo, on the other hand, is more of a typical tenore amoroso, with music that is both lyrical and passionate at the same time.”

“I think the musical conventionality of Giorgio and Alfredo Germont serves to emphasise the two characters’ rather bourgeois attitudes. Giorgio Germont clearly personifies the hypocritical bourgeoisie who make Violetta and Alfredo’s love affair in the second act an impossibility, but Alfredo is far from being a hero either. He is very much driven by his own emotions and needs. When he aggressively insults and humiliates Violetta during the party in the second act by telling everyone he pays for her favours, we see he has not really been able to break with his bourgeois background.”

Violetta’s death

In the third and final act, Violetta is on her deathbed, where she sings the moving aria ‘Addio del passato’. “At this point, the action pauses and Verdi gives us an insight into Violetta’s soul. The aria starts with a wonderfully pure vocal line, then the tempo speeds up slightly and the words she sings become ever more intense — because text and music always go hand in hand for Verdi. The second stanza of this aria is often left out in performances but we decided to keep it in. The text here is even more dramatic and harrowing: Violetta sings about her grave and how no one will leave flowers there or shed a tear for her. The aria ends with a filo di voce, a faint vocal line where you almost hear the life ebbing from Violetta. It’s a moment that can’t fail to move you.”

Several decades after La traviata, Giacomo Puccini let another courtesan die on stage in La bohème. But whereas Puccini’s Mimi expires almost imperceptibly in silence, Violetta’s death is quite different: an extensive affair in which she even seems briefly to find renewed energy at the end, before collapsing. “That difference is because La bohème aims for realism whereas La traviata is still much more in the Romantic tradition. You see that too in Verdi’s other operas from this period, such as Rigoletto. To have Gilda singing the finale after she has been stabbed and stuffed into a sack is hardly realistic… These operas are connected by a certain Romantic ambience that fetishises lengthy female death scenes. If you look at the Romantic literature from this period, you see the same fascination with dying women.”

But today’s audiences still need Violetta’s protracted tragic death, argues Battistoni. “The audience has accompanied her and empathised with her throughout the opera. We desperately want it to end well for her after all. But what if Doctor Grenvil were to suddenly offer Violetta a medicine that cures her at once? Then the opera would be much less satisfying as an artwork. Like so much fiction, an opera like La traviata lets us experience the cruel and painful side to life. It shows us that things don’t always work out for the best, however much we want them to. And that is the power of art.”

Interview: Laura Roling

The populated desert

An interview with stage director Tatjana Gürbaca

The populated desert

An interview with stage director Tatjana Gürbaca

Giuseppe Verdi was a political composer, as is evident from Rigoletto, Il trovatore and La traviata. In all three operas, the composer turns characters on the margins of society into tragic main protagonists on the stage.

“Absolutely. Indeed, Verdi repeatedly had run-ins with the censors throughout his life. To give an example, when Verdi composed Rigoletto, Victor Hugo’s Le roi s’amuse, the play on which Rigoletto was based, was still banned. In the case of his opera Un ballo in maschera, he had to change the setting because an opera about a historical regicide was too close to the bone for the censors: he had to set the action in America instead. The historical character on which La traviata is based, the courtesan Alphonsine Duplessis, died in 1847 aged only 23. One year later, Alexandre Dumas fils published the novel La dame aux Camélias, soon to be followed by a stage adaptation. So when Verdi decided to make this the subject of an opera, it was still highly topical. The historical Duplessis had only been dead six years when the opera premiered in 1853.”

Verdi wanted his operas to reflect the social conditions of his day and to take a stand.

“Yes. Even in his operas that are set in the distant past, such as Don Carlos or Macbeth, he managed to tell the story in such a way that it had a message for his own day. His operas still have that force nowadays. Verdi’s stories deserve to continue to be told, especially La traviata!”

“I feel Violetta makes a crucial statement in the first act when she describes Paris as a popoloso deserto, a populated desert. She is referring to a kind of society we are still familiar with today: soulless people who have no empathy and who worship money – just one-dimensional consumers in a large city. Anyone who fails to observe the unwritten rules of this society driven by money is punished mercilessly — like Violetta at Flora’s party in the second act. After all, the owner can’t allow his toy to escape.”

In La traviata, Verdi imbues the life and death of a prostitute with tragic grandeur. The term ‘courtesan’ is somewhat euphemistic and overly glamorous. In one of his letters, Verdi is blunter, calling her a ‘whore’.

“Verdi’s decision to make someone with this profession the central character is striking as the serious operas of his day were mainly about historical figures, rulers, amorous aristocrats and madmen. The characters were always elevated in some way. Verdi’s choice of a story from everyday life in which a marginalised individual is the main character is incredibly modern.”

Beautiful, fragile, unselfish, ailing and erotic — isn’t Violetta the epitome of the typical female victim we see in so many nineteenth-century operas?

“On the contrary. She is an incredibly modern character and thoroughly emancipated. She is a highly successful ‘material girl’, the queen of Paris’s most exclusive parties where the city’s rich gather. She is the most desirable prostitute and earns vast amounts of money through her work.”

“It is her illness that brings her to a deeper insight. It makes her ask herself what she wants to do with the time left to her now that she no longer needs to continue earning money. For the first time, she spies an opportunity to make a life for herself according to her own wishes. When she meets Alfredo at the party in the first act, she sees him as a route to a different life. He offers her something her world was lacking: love. After all, anything is permitted in Parisian society except having feelings. Love is a dangerous luxury that you can’t afford because it makes you weak and vulnerable. Even so, I don’t see that encounter with Alfredo as love at first sight. It is more a case of Alfredo being Violetta’s new project. For the first time, she can offer herself not in return for money but from a sense of sacrifice.”

“I find it fascinating how the role of money in the opera is tied so closely to Violetta’s story. In the first act, Violetta earns her own money. In the second act, she sells all her possessions to finance her life in the countryside with Alfredo. In the third act, she gives away her money to the poor. As death approaches, money loses its value for her.”

What is it exactly that kills Violetta? What does her suffering a terminal disease mean?

“I’m not that interested in which specific disease it is that afflicts Violetta. What’s more important is that her disease acts as a catalyst prompting her to take leave of the world she was living in. Suddenly Violetta looks at her surroundings through new eyes and she realises she no longer wants to be a part of it. I think Verdi saw the disease as symbolic to some extent. Unlike Puccini, for instance, Verdi was not a strict realist.”

Verdi expressly forbade the singer playing the role of Violetta to cough in the third act, when she is dying of tuberculosis.

“That is correct. It is not simply about a physical disease. In my view, Violetta is killed by the emotional sterility of this world. When she dies, the music doesn’t end on a quiet or tender note but with a fanfare. The character of Violetta has great revolutionary potential, and she ends her life with an act of resistance. When we started preparations for this production, the Occupy movement was at its height in Spain. Women were dancing the flamenco in front of banks as a form of protest, to draw attention to the country’s culture and what truly matters rather than money. They were taking a stand for their dignity. The same applies to Violetta.”

Is it telling that Violetta dies of tuberculosis?

“Yes, having her die of a lung disease is very apt. She suffocates, she can’t breathe in the ‘populated desert’ she finds herself in. Spitting blood, a symptom of tuberculosis, suggests an internal rotting process as well. It is as if she is bleeding to death inside.”

Why does Violetta fall in love with Alfredo of all people, a naive newcomer from the provinces?

“There is a poignant moment in Dumas’ novel when she says, ‘It is enough for someone to look at me with pity when I cough’. It seems Alfredo is the only one to show her pity. It is precisely because he is not part of Parisian society and doesn’t know the rules or play the dirty games. It is his naivety, innocence and frankness that attract Violetta at first and that she finds so moving.”

“But in the end it is Alfredo’s naivety that causes the relationship to fail. He turns out to be a dreamer incapable of decisive action. When they retreat to the countryside, he doesn’t even realise for ages that Violetta is financing their life together. In fact, this is a radical role reversal: rather than being paid by men, Violetta is now the one paying for a man. Perhaps this is going too far, but you could call Alfredo the prostitute in this relationship.”

“It is also striking that Verdi doesn’t give the couple a love duet in the scene in the countryside. It is as if Violetta and Alfredo live separate lives, and in fact they barely meet on the stage.”

After he humiliates Violetta at Flora’s party in the second act, Alfredo immediately regrets his cruel behaviour. So why doesn’t he return to the ailing Violetta earlier in the third act?

“That is because his father, Giorgio Germont, has successfully forced Alfredo into a conventional way of life whether Alfredo likes it or not. I believe there are other factors at play too. Alfredo misjudges the situation; he doesn’t realise what Violetta’s true condition is. I also feel he is afraid to see her again, as that would mean Violetta and Alfredo having to talk about what went wrong between them. That would take this great love affair into the realm of reality, where it does not belong. From the start, their love consists of projections on both sides. If the two lovers were to be honest with each other, that would severely damage the ideal image that each has of the other.”

Is Giorgio Germont the villain who drives the lovers apart because he demands Violetta give up Alfredo?

“No! Many productions position him as Violetta’s real opponent. But if you consider the situation he is in, his character becomes extremely complex and interesting. Germont is from a different generation to Alfredo and Violetta and has very different values. He has a heart, as is made clear by the wonderful music when he sings of his home and family. What counts for him is family, not money. As a father, he does everything he can to look after his family, even if that means he has to be tough.”

“He is also the only character in the opera who doesn’t have a noble title or come from Paris — he is from Provence. It seems he has come to Paris to conduct business with the nobility. Accordingly, he is under great pressure to find some way into this society and become part of it. In Verdi’s operas, pressure from a group or community often sets off tragic or catastrophic decisions, actions and events. That is also the case for Germont’s actions.”

When Germont visits Violetta on her deathbed, he asks her forgiveness. That must mean he is only too aware of what he did to her.

“That Germont is aware of what he has done may make it only worse. Someone who does something without understanding what it implies is amoral because they have no morals. Germont, on the other hand, is immoral because he knows the harm he is inflicting upon Violetta and yet he still does it.”

Is Violetta’s real opponent society as a whole — as so often in Verdi’s work?

“The real opponent is the social structure within which Violetta operates. That’s why we will have the chorus on stage more than is strictly required according to the musical score. The chorus is important both as an antagonist and as the backdrop for Violetta’s actions. The most dramatic moments are the contrapuntal ones when Violetta breaks free of social conventions, rebels and immediately forms a serious threat to the social structure. An example is the big duet with Germont and Violetta. Germont has persuaded her to give up Alfredo so that his sister can have a better life. Suddenly the music changes course. Violetta sings ‘Morrò’ (I will die), but rather than being passive and resigned the music is full of fight, almost aggressive. Her death sounds more like a threat here. Women like Violetta are dangerous precisely because they know so much about the powerful men in society. They really could disrupt the established order.”

Interview: Bettina Auer

Based on a translation from German into Dutch by Laura Roling

Rhythm 0

Rhythm 0

Rhythm 0

One of the sources of inspiration for the director Tatjana Gürbaca was Rhythm 0, a 1974 work by the Serbian performance artist Marina Abramović. The performance was a compelling illustration of the fatal consequences that the objectification of a fellow human can have.

In a performance lasting six hours in Studio Morra in Naples, Abramović turned herself into an object. Seventy-two items were laid out on a table, including a rose, a feather, perfume, honey, bread, grapes, wine, scissors, razor blades, nails and a loaded gun. Visitors were free to do whatever they wanted with the objects and with Abramović.

It started with innocent interventions, like moving an arm, but some participants soon started to exhibit more extreme behaviour. They used the razor blades to remove Abramović’s clothing and then started cutting Abramović herself with the blades. One person even cut her neck and drank her blood. Eventually the loaded gun was placed in Abramović’s hand and pointed at her, while her finger was placed on the trigger. At that point a fight broke out between the members of the audience.

Abramović said later, “This work taught me that if you give the audience complete control, it can kill you. I felt that my body had been violated: they cut my clothes, they stuck the thorns of a rose in my stomach… Someone even pointed the gun at my head and someone else took it away. The atmosphere turned aggressive. After precisely six hours, as planned, I stood up and started to walk towards the audience. Everyone took off fast to avoid having to confront me.”

The courtesan

De courtisane

The courtesan

Courtesans often tend to be romanticised. Not without reason, as the life of a courtesan certainly had its glamorous aspects. Courtesans were not women you hired for the night (or by the hour). They were kept in style for long periods by wealthy lovers, prominent men who provided them with accommodation, an extremely generous allowance and every luxury. What the men received in exchange was not just sex: the courtesan had to be a captivating companion, capable of holding an entertaining conversation with highly educated men occupying leading positions in society. With her beauty, intelligence and charm, the courtesan stood at the top of the prostitution pyramid.

But the glamour frequently hid deep suffering, as is testified by the life of the real-life courtesan Marie Duplessis, the woman on whom Dumas’ Marguerite Gautier and Verdi’s Violetta Valéry are based. She was born in 1824 in rural Normandy as Alphonsine Plessis. Her family was poor and dominated by her violent and alcoholic father. Alphonsine was taught to read and write a little in preparation for her Confirmation in the local church, but that was the full extent of her formal education.

At the age of twelve she was already being prostituted by her own father. When she moved to Paris aged fifteen, she became one of the city’s many grisettes, young working women who supplemented their meagre wages by offering men company in return for a meal, small presents or an evening out on the town. Grisettes were the ideal prostitutes for impecunious male students. Mimi in Puccini's La bohème is a typical grisette, a young woman of humble origins living in a shabby attic room and earning her income in part as a seamstress.

Alphonsine used her contacts with the students to educate herself, soaking up knowledge and skills like a sponge. She progressed from grisette to lorette, a prostitute who can live comfortably off her earnings and does not need to do any other work, but as a consequence loses any vestige of respectability in society. The lorette had little financial security: her clients might have money to spend, but not in endless amounts. She therefore had to make sure she always looked her best when out in public, to keep improving her knowledge and skills in all areas and to draw the right kind of attention in the hope of climbing the ranks and becoming a courtesan.

Which Alphonsine indeed managed. She changed her name to Marie Duplessis — the addition of ‘Du’ suggesting noble ancestry — and broadened her clientele to include aristocrats and artists. The first signs of tuberculosis (consumption) appeared three years before her death. In the nineteenth century, TB was a fatal and widespread lung disease that killed as many as one in seven people. Marie Duplessis died in 1847 aged only 23, although it is not entirely clear whether this was due to the tuberculosis or a sexually transmitted disease such as syphilis — another possibility.

What is certain is that Marie Duplessis, unlike the fictional characters based on her, never made any attempt to give up her life as a courtesan. On the contrary, in the course of her brief life she had climbed to the pinnacle of her profession. That is evident from a letter sent by the author Charles Dickens, who was staying in Paris when she passed away. “For several days all questions political, artistic, commercial have been abandoned by the papers. Everything is erased in the face of an incident which is far more important, the romantic death of one of the glories of the demi-monde, the beautiful, the famous Marie Duplessis.”

Text: Laura Roling

Programmaboek

Become a Friend of Dutch National Opera

Friends of Dutch National Opera support the singers and creators of our company. That friendship is indispensable to them, and we are happy to do something in return. For Opera Friends, we organise exclusive activities behind the scenes and online. You will receive our Friends magazine and have priority in ticket sales.