Lohengrin

Content

- Performance information

- In a nutshell

- The story

- Timeline: Lohengrin in dates

- In conversation with director Christof Loy

- An interview with artist and set designer Philipp Fürhofer

- Wagner’s last Romantic opera

- On Lohengrin’s composition and musical innovations

- Lohengrin as an expression of Wagner’s worldview

- Biographies artistic team

- Biographies singers

Performance information

Voorstellings-informatie

Performance information

Lohengrin

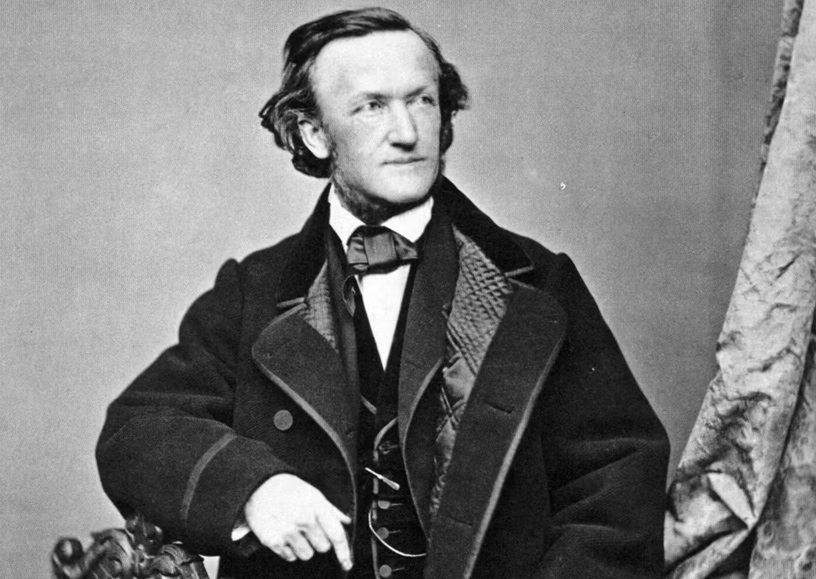

Richard Wagner (1813-1883)

Duration

4 hours and 30 minutes, including two intervals

This performance is sung in German with Dutch and English surtitles.

Romantic opera in three acts

Makers

Libretto

Richard Wagner

Musical direction

Lorenzo Viotti

Stage directon

Christof Loy

Associate director

Georg Zlabinger

Set design

Philipp Fürhofer

Costume design

Barbara Drosihn

Lighting design

Cor van den Brink

Video

Ruth Stofer

Choreography

Klevis Elmazaj

Dramaturgy

Niels Nuijten

Cast

Heinrich der Vogler

Anthony Robin Schneider

Lohengrin

Daniel Behle

Elsa von Brabant

Malin Byström

Friedrich von Telramund

Thomas Johannes Mayer

Ortrud

Martina Serafin

Der Heerrufer des Königs

Björn Bürger

Vier Brabantische Edle

Christiaan Peters

François Soons

Harry Teeuwen

Jeroen de Vaal

Edelknaben

Taylor Burgess

Vida Matičič Malnaršič

Elsa Barthas

Yvonne Kok

Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra

Chorus of Dutch National Opera

Chorus master

Edward Ananian-Cooper

Production team

Assistant conductor

Aldert Vermeulen

Junior assistant conductor

Alejandro Cantalapiedra

Assistant director

Astrid van den Akker

Assistant director during performances

Astrid van den Akker

Intern stage direction

Arthur Buchholz

Rehearsal pianists

Ernst Munneke

Irina Sisoyeva

Language coach

Franziska Roth

Language coach Chorus

Cora Schmeiser

Assistant chorus masters

Ad Broeksteeg

Kuo-Jen Mao

Stage managers

Marie-José Litjens

Roland Lammers van Toorenburg

Emma Eberlijn

Julia van Berkel

Artistic planning

Vere van Opstal

Orchestra inspector

Frouke Terpstra

Assistant stage design

Manuel Curiman

Assistant costume design

Oliver Velthaus

Costume supervisor

Maarten van Mulken

Master carpenters

Wim Kuijper

Jop van den Berg

Lighting manager

Peter van der Sluis

Props manager

Peter Paul Oort

Special Effects

Ruud Sloos

Koen Flierman

First dresser

Jenny Henger

First make-up artist

Trea van Drunen

AVM producer

Jonna van den Berg

Sophie Gipmans

Camera operator

Chantal Bergemann

Sound technician

David te Marvelde

Titelregie

Eveline Karssen

Surtitle operator

Irina Trajkovska

Head of music library

Rudolf Weges

Set supervisor

Puck Rudolph

Production management

Emiel Rietvelt

Chorus of Dutch National Opera

Sopranos

Patricia Attele

Diana Axentii

Lisette Bolle

Taylor Burgess

Caroline Cartens

Marion Dumeige

Nicole Fiselier

Melanie Greve

Deasy Hartanto

Maaike Hupperetz

Simone van Lieshout

Tomoko Makuuchi

Vida Matičič Malnaršič

Vesna Miletic

Sara Moreira Marques

Sara Pegoraro

Elizabeth Poz

Janine Scheepers

Jannelieke Schmidt

Kiyoko Tachikawa

Altos

Marion van den Akker

Irmgard von Asmuth

Elsa Barthas

Ellen van Beek

Anneleen Bijnen

Daniella Buijck

Rut Codina Palacio

Johanna Dur

Valérie Friesen

Yvonne Kok

Fang Fang Kong

Carlijn Kooijmans

Myra Kroese

Itzel Medicigo

Maria de Moel

Sophia Patsi

Marieke Reuten

Carla Schaap

Klarijn Verkaart

Ruth Willemse

Tenors

Gabriele Bonfanti

Thomas de Bruijn

Wim-Jan van Deuveren

Milan Faas

Ruud Fiselier

Cato Fordham

Livio Gabrielli

Dimo Georgiev

Pablo Gregorian

John van Halteren

Erik Janse

Stefan Kennedy

Robert Kops

Leon van Liere

Raimonds Linajs

Roy Mahendratha

Tigran Matinyan

Frank Nieuwenkamp

Sullivan Noulard

Martin van Os

Dean Parker

Richard Prada

Mirco Schmidt

Raymond Sepe

François Soons

Julien Traniello

Jeroen de Vaal

Bert Visser

Rudi de Vries

Basses

Ronald Aijtink

Peter Arink

Bora Balci

Nicolas Clemens

Emmanuel Franco

Jeroen van Glabbeek

Julian Hartman

Agris Hartmanis

Hans Pieter Herman

Sander Heutinck

Tom Jansen

Roele Kok

Matthijs Mesdag

Maksym Nazarenko

Gulian van Nierop

Christiaan Peters

Hans Pootjes

Matthijs Schelvis

Jaap Sletterink

Rene Steur

Harry Teeuwen

Rob Wanders

Marijn Zwitserlood

Dancers

Nicky van Cleef

Clara Cozzolino

Oskar Eon

Jaroslaw Kruczek

Carla Pérez Mora

Guillaume Rabain

Anton van der Sluis

Giulia Tornarolli

Sien Vanderostijne

Riccardo De Totero

Sandra Pericou (backup)

Luigi Vilotta (backup)

Child extras

Ebel Pearson

Brent Gunneweg

Children's guidance

Manon Wittebol

Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra

First violin

Ionel Manciu

Saskia Viersen

Koen Stapert

Paul Reijn

Derk Lottman

Maria Rodriguez Estevez

Marieke Kosters

Tessa Badenhoop

Henrik Svahnström

Sandra Karres

Hike Graafland

Irene Nas

Marina Malkin

Novile Maceinaite

Julia Kleinsmann

Eva Traa

Marijke van Kooten

Second violin

David Peralta Alegre

Mintje van Lier

Marlene Dijkstra

Karina Korevaar

Wiesje Nuiver

Eva de Vries

Marieke Boot

Floortje Gerritsen

Anita Jongerman

Lotte Reeskamp

Lilit Poghosyan Grigoryants

Charlotte Basalo Vázquez

Jarmila Delaporte

Joanna Trzcionkowska

Inge Jongerman

Viola

Roeland Jagers

Laura van der Stoep

Marjolein de Waart

Odile Torenbeek

Suzanne Dijkstra

Lotte de Vries

Avi Malkin

Anna Smith

Stephanie Steiner

Nadia Debono

Madi Luimstra

Liselot Blomaard

Geerten Feller

Cello

Georgi Anichenko

Nuala McKenna

Douw Fonda

Nitzan Laster

Rik Otto

Celia Camacho Carmena

Carin Nelson

Veerle Schutjens

Anjali Tanna

Nil Domènech Fuertes

Atie Aarts

Sebastian Koloski

Double bass

Luis Cabrera Martin

Mario Torres Valdivieso

Gabriel Abad Varela

Sorin Orcinschi

Julien Beijer

Marí Ángeles Ruiz Bolancé

Peter Rikkers

Dobril Popdimitrov

Erik Spaepen

Flute

Leon Berendse

Ellen Vergunst

Andreia Serra da Costa

Oboe

Jeroen Soors

Juan Pedro Martinez García-Casarrubios

Maxime le Minter

Clarinet

Leon Bosch

Annemiek de Bruin

Peter Cranen

Bassoon

Margreet Bongers

Dymphna van Dooremaal

Jaap de Vries

Horn

Fokke van Heel

René Pagen

Miek Laforce

Stef Jongbloed

Fred Molenaar

Trumpet

Ad Welleman

Jeroen Botma

Marc Speetjens

Trumpet on stage

Gertjan Loot

Tonnie Kievits

Jacq Sanders

Erik Torrenga

Hans van Loenen

David Pérez Sanchez

Tiago Baeza

Niek Jacobs

Sjoerd Pauw

Rudolf Weges

Trombone

Harrie de Lange

Joao Mendes Canelas

Wim Hendriks

Dick Bolt

Tuba

David Kutz

Timpani

Marc Aixa Siurana

Percussion

Matthijs van Driel

Diego Jaen Garcia

Nando Russo

Harp

Sandrine Chatron

Organ

Ernst Munneke

Lohengrin in a nutshell

Lohengrin in het kort

Lohengrin in a nutshell

Wagner: composer and librettist

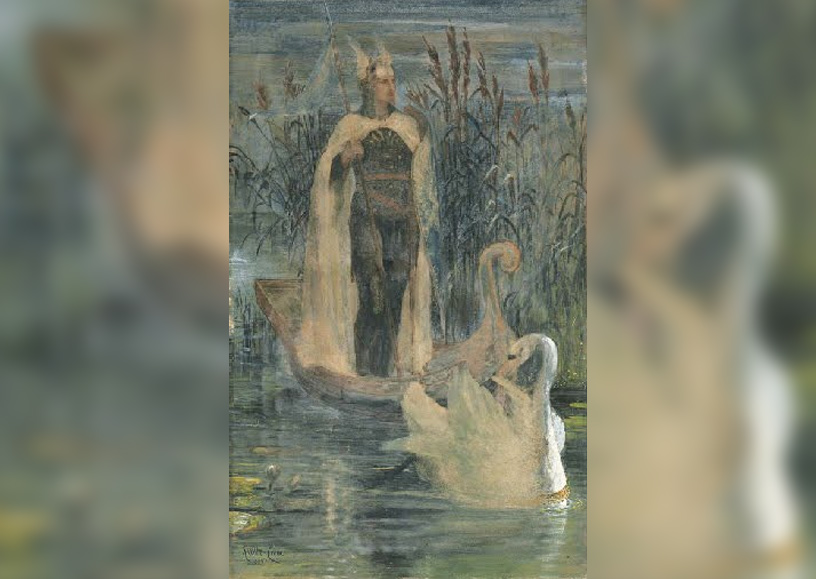

The libretto for Lohengrin was written by the composer himself. It is based on various tales about Lohengrin, one of the mythical Knights of the Holy Grail. The stories date back to the medieval epic Parzival by Wolfram von Eschenbach. Wagner would subsequently use the same source for another opera, this time about Parsifal, Lohengrin’s father.

Wagner’s last ‘opera’

After Lohengrin, the composer said goodbye to the term ‘opera’ as a designation for his compositions. Henceforth, the music and the story would no longer be divided into recitatives and arias, but the entire work would form one continuous whole. In Lohengrin, the move to this new form is already evident.

Director Christof Loy

After Wagner’s Tannhäuser (2019), director Christof Loy returns to Dutch National Opera for his second Wagner production. As director, he once again puts the characters and their experiences centre stage. The sets for this production were created by German artist and designer Philipp Fürhofer. His work is characterised by the use of mirror foil, painting elements and lighting effects.

Large opera chorus

The chorus is at the heart of this work. Nearly one hundred singers are on stage representing the peoples of Brabant, Saxony and Thuringia. The threat of war looms large, and the outcome of Elsa’s tragic love story and the concomitant power struggle may just determine the fate of the people as a whole.

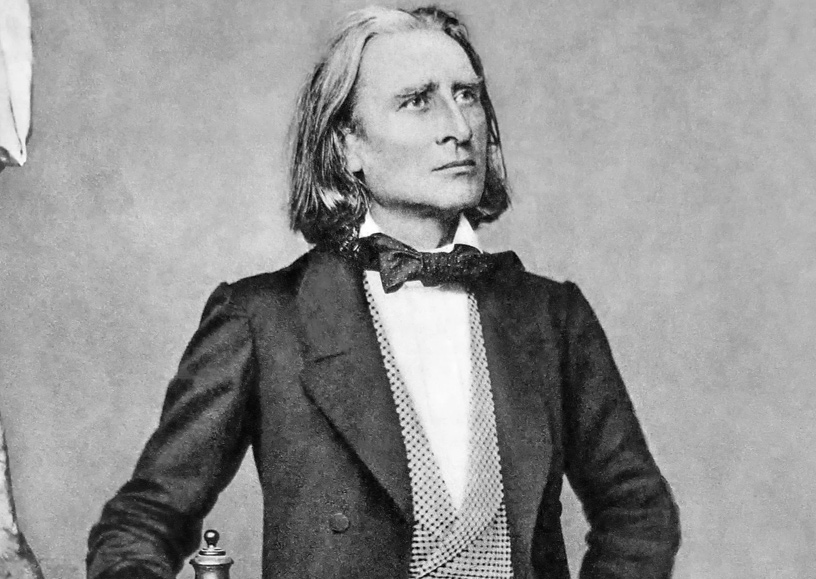

The premiere

Wagner did not attend the premiere of Lohengrin. An order had been issued for his arrest due to his influential role during the Dresden uprising in 1848, and he had been forced to flee the city and country. His good friend (and later father-in-law) Franz Liszt conducted the premiere in Weimar in 1850 and passed on detailed reports to the composer. When Wagner eventually did attend a performance of Lohengrin in 1861, he remarked that he was probably the only remaining German who had not yet seen the opera.

Viotti’s first Wagner

Lorenzo Viotti, chief conductor at Dutch National Opera and the Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra, has been invited several times to conduct a Wagner opera and now – finally – he is. Viotti’s long-awaited first Wagner will be in Amsterdam with his own orchestra, where he can fine-tune his interpretation down to the smallest details.

The story

Het verhaal

The story

King Heinrich comes to Brabant to raise an army in the fight against an enemy approaching his kingdom’s eastern frontier. He arrives to find a tense situation. Count Friedrich of Telramund has accused Elsa of Brabant of the murder of her brother Gottfried, the rightful heir to the deceased Duke. Moreover, given the suspicious circumstances, he is claiming power himself. King Heinrich decides the dispute must be settled by a duel. Telramund will have to fight a knight who is willing to defend Elsa. Then a strange being appears borne by a swan, a knight Elsa had already seen in her dreams. He is prepared to fight for Elsa and even to marry her, on one condition: she must never ask his name or where he comes from. Elsa agrees and the unknown knight defeats Telramund.

After this humiliating incident, Telramund and his wife Ortrud plot revenge. Ortrud tries to gain Elsa’s confidence and sow doubt about the intentions of her betrothed. On the way to the wedding ceremony, Ortrud and Telramund confront the couple. They accuse the knight publicly of sorcery and Telramund demands that he reveal his identity. In the end, the knight asks Elsa if she still stands by her promise not to ask him his name. Elsa has begun to have doubts, but ultimately she confirms her trust in him and the marriage is concluded.

When the newly wedded couple are alone, Elsa cannot resist the urge and asks the fatal question after all. At precisely that moment, Telramund bursts in, armed. The knight soon finishes his attacker off. He decides to reveal his identity in front of the king and the people. He announces that he is Lohengrin, a Knight of the Holy Grail and son of Parsifal. After this revelation, all he can do is return to the holy kingdom of his father. As he departs, the swan he arrived on is transformed into a young man: Elsa’s brother Gottfried, the new Duke of Brabant. Lohengrin slowly disappears from view and Elsa falls to the ground.

Timeline

Lohengrin in dates

Timeline: Lohengrin in dates

919-936

The reign of King Henry I of the East Frankish Empire. He was nicknamed ‘The Fowler’ for his love of hunting. He is seen as the first king to rule a medieval German state, managing to expand its borders with his ambitious wars and military campaigns.

Around 1200

Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzival epic dates from around 1200. It consists of a series of books about Parzival, a Knight of the Holy Grail, based in turn on the tales of Percival, one of the knights of the mythical King Arthur. The story about Parzival’s son Loherangrin appears in one of the last books in the series.

1813

Richard Wagner is born in Leipzig on 22 May. His father dies six months after his birth and his mother remarries. Her new husband is the German actor and playwright Ludwig Geyer, who introduces Wagner to the theatre. At the age of nine, Wagner sees Carl Maria von Weber’s Der Freischütz, which sparks off his love of music and opera.

1841

Wagner reads the 1838 book Über den Krieg von Wartburg by Christian Theodor Ludwig Lucas. The book seeks to give a historical interpretation of German medieval sagas, and will later serve as inspiration for two of Wagner’s operas: Tannhäuser and Lohengrin.

1842

Wagner is appointed conductor of the Hofkapelle and Hofoper in Dresden. Both Der fliegende Holländer and Tannhäuser would premiere here.

1845

Immediately after the premiere of Tannhäuser on 19 October, Wagner starts work on the libretto for Lohengrin. He begins composing the music not long after. Six months later, in May 1846, he has an initial version of the musical score.

1848

Wagner completes the score for Lohengrin on 28 April. To celebrate the tercentennial anniversary of the Dresden Hofkapelle, he conducts a concertante performance of the final part of the first act. A performance of the opera in its entirety is scheduled for one year later.

1849

The scheduled premiere of Lohengrin is cancelled because of Wagner’s involvement in the May Uprising in Dresden. A major reason for the uprising is the desire for German unification, of which Wagner is a fierce advocate. In that regard, he sees King Henry the Fowler as a shining example. The revolution fails and on 9 May Wagner flees Dresden and finds refuge in Switzerland.

1850

On 28 August, Lohengrin receives its premiere in Weimar with Franz Liszt conducting. Wagner cannot be there himself as there is a warrant out for his arrest. In the run-up to the performances, he maintains an energetic correspondence with Liszt in which he gives tips for the music and staging.

1853-1860

Wagner conducts extracts from Lohengrin in various concert tours throughout Europe. In July 1860, Germany grants Wagner partial amnesty: he is allowed on German soil again but is not allowed to set foot in the Kingdom of Saxony, the territory of his former employer.

1861

Wagner conducts a stage performance of Lohengrin for the first time, in Vienna. In that same year, the Bavarian crown prince, who would later become King Ludwig II, attends a performance of Lohengrin in Munich. He is deeply moved by the opera and becomes a huge aficionado of Wagner.

1862

Lohengrin is performed for the first time in the Netherlands, by the Hoogduitsche Opera in Rotterdam. The first performance in Amsterdam is not until 1868.

1868-1886

King Ludwig II builds the castle of Neuschwanstein at the foot of the Alps. The castle is inspired by Wagner’s Lohengrin and even has murals depicting scenes from the saga.

1883

Richard Wagner dies in Venice.

1894

Lohengrin is performed for the first time at the Bayreuther Festspiele, the festival Wagner himself founded in the Festspielhaus he built in Bayreuth, a town in southern Germany. Wagner’s widow Cosima takes charge of the artistic aspects of the production.

1972

In September, Dutch National Opera performs Lohengrin for the first time. The conductor is Edo de Waart, and Filippo Sanjust is responsible for the stage direction.

2019

The German director Christof Loy directs Tannhäuser, his first Wagner opera for Dutch National Opera. Loy is already well acquainted with Wagner’s oeuvre by that point, as he directed his first Tannhäuser ever in 1995.

2023

Christof Loy directs Lohengrin, his second Wagner opera for Dutch National Opera.

Dismantling a utopia

In conversation with the director Christof Loy

Dismantling a utopia

In conversation with the director Christof Loy

After his Tannhäuser in 2019, the German director Christof Loy is returning to direct his second Wagner for Dutch National Opera. He shares his thoughts on this ambitious work with dramaturg Niels Nuijten.

Lohengrin fits well with the last two productions you created for Dutch National Opera, Tannhäuser and Königskinder. All three are grand Romantic operas with fantastical stories.

“This does indeed seem to have turned into a kind of series of major German operas. However, I actually find Lohengrin the stronger fairy tale compared with Königskinder. Königskinder plays with fairy-tale elements, as it were, but in the final analysis, the story is quite down to earth. Everything has a rational explanation and I was able to embed the action in the real world. The witch isn’t a real witch, and even the lovers’ death from eating the enchanted bread can be seen as a deliberate decision to leave this world. But with Lohengrin, I really need to embrace the supernatural elements. I need to believe in the forces of dark and light operating here, and in the magic of the Knight of the Grail, otherwise it doesn’t work.”

Yet in the midst of the enchantment and the forces of good and evil is a real-life situation: that of a nation in crisis.

“You need to take the psychology of the masses and of the individuals seriously, even in this fairy-tale context. The opera does indeed begin in a crisis situation, on multiple fronts. There is a threat of war in the East and the German King comes to Brabant to raise troops and defeat their common enemy. But the people of Brabant are embroiled in their own internal crisis. The old Duke has died and his heir, Gottfried, has gone missing. There are rumours that his sister Elsa has disposed of her brother so that she can assume control. This accusation cannot be proved and is largely fuelled by Telramund and his wife Ortrud. She comes from an ancient dynasty of rulers and seeks to claim power for her husband and herself. The people are divided, and the outcome of this dispute will determine Brabant’s future. Ortrud represents the old gods, of course – Wotan and his entourage. She is all about the rule of the strongest, and consequently an undemocratic system. Elsa, on the other hand, is a kind of Virgin Mary figure who symbolises the new, Christian religion and a more enlightened kind of rule.”

Two men arrive in Brabant in short succession and are confronted with this situation: first the German King Heinrich and then Lohengrin.

“The King has an interest in resolving the problems in Brabant. He decides there should be a trial by ordeal, a duel between two combatants in which it is assumed God will ensure victory for the person in the right. Of course this is the just, Christian God. Elsa is not able or permitted to fight on her own behalf in this medieval context of a male-dominated society, so a knight must be found who is willing to defend her. This is the point at which the wondrous and magical elements enter the story, with the arrival of Lohengrin.”

What kind of a figure is Lohengrin actually for you?

“During the period when he was writing Lohengrin, Wagner was thinking a lot about Jesus of Nazareth and even had plans to create an opera about him. God ‘becoming man’ was something Wagner was very interested in and we see that reflected in the character of Lohengrin. He is the Redeemer, which also makes him a very lonely figure who bears a great burden of sorrow. It as if he too needs to be redeemed. It was only during rehearsals that I discovered I actually see Lohengrin as a cursed individual – a little like Der fliegende Holländer, where the mysterious captain drops anchor once every seven years, only to be disappointed every time. I think Lohengrin knows this will inevitably be his fate too, and his arrival in Brabant feels like déjà vu for him. He gets a hero’s reception as their saviour, but he seems to realise it won’t last long. He knows humanity isn’t capable of true faith. My interpretation of him forbidding the question is that he is saying: don’t interrogate me, just take me as I am. Believe in me.”

You could also argue it is hardly surprising that people want to know where their leader or lover comes from before they are prepared to trust them completely.

“I always used to think what Lohengrin demands of Elsa is awful, but I’ve changed my mind; I see the situation differently nowadays. The power of the story lies precisely in that request for trust. Wouldn’t it be lovely if we could make our way through life assuming we all want the best for each other, and that we can continue to trust one another absolutely rather than having to lose our childlike naivety? Of course I realise this is a pipe dream. Indeed, I see Lohengrin as dismantling that utopia. At the heart of this issue of trust is Elsa. At first, she has this pure naivety, which I don’t see as a sign of weakness or gullibility at all — far from it. Elsa has a kind of determined stubbornness, which pulls her through the first act. However, in the second act, Ortrud and Telramund start to chip away at her determination, causing her faith to waver until she finally asks Lohengrin the fateful question. The point at which she asks the question is often interpreted as Elsa’s emancipation, but I find it a sad if inevitable moment. It reminds me of how people who don’t believe in God suddenly start praying during a calamity. They call on God when the situation is perilous, as is the case at the start of this opera, but as soon as the danger has receded they start to doubt and reason takes over again. That is why Elsa and the people ultimately have to take leave of Lohengrin. Once a god has to provide proof of his authenticity, he becomes superfluous.”

In fact, all the characters believe in something, but in the final analysis we see that everyone’s faith is found wanting.

“Absolutely. Even Lohengrin wants to believe that it may perhaps work out well this time, yet the situation still turns out to be unsustainable. I see Telramund as a counterpart to Elsa: he is just as gullible as she is, except he is influenced by Ortrud. The people see him as honest and genuine, so they are prepared to believe him and follow him. That is why his accusations — first of Elsa and later of Lohengrin — are taken so seriously. It also makes him the perfect pawn for Ortrud to use to bring her plans to fruition. She abuses his credulity and credibility. In the opera, he doesn’t lie. His tragedy is that he put his trust in the wrong person.”

Lohengrin more or less marks the middle point of Wagner’s oeuvre. Unlike his later works, this opera is still made up of clearly distinguishable arias, recitatives and chorus pieces. Is that something you focus on in your stage direction?

“I certainly notice the choices the composer made, especially the contrasts. The celebratory chorus that ends the first act obviously can’t be repeated at the end of Act II, so Wagner decides to have a kind of recitative scene in the grand opéra style. I’m aware of these structures but they aren’t something I focus on in telling this story. In fact, it’s precisely the striking, unusual aspects of the composition that interest me most. An example is the constant presence of the chorus in the first act, for over an hour. I have hardly ever seen that in other operas. Something else I also concentrate on is the extreme fragility of the music, especially in the prelude. The sounds are like grains of sand that gradually slip between your fingers. I always have that image in my mind during this creative process, as a metaphor for the life we can’t hold onto. Then, of course, you have the contrast of the grand, bombastic passages. The music navigates between fragility and violent disruption. On top of that, you have recurring references to the metaphysical, for example in the opera’s many prayers. Musically too, this work is one long exposition on faith.”

Text: Niels Nuijten

Transformation from a static position

An interview with artist and set designer Philipp Fürhofer

Transformation from a static position

An interview with artist and set designer Philipp Fürhofer

The sets in this production of Lohengrin were created by the German artist and designer Philipp Fürhofer, whose work stands out for its combination of mirror film, painting and light effects. He talks to us about his designs for this opera.

The stage setup for Lohengrin is on a grand scale, reminiscent at first sight of a factory hall. How would you describe the space?

“It is an ambivalent space. It feels industrial to some extent, but it also reflects the religious architecture we are familiar with from churches and basilicas. For example, the space is divided into a high middle section, a kind of nave, with aisles on either side separated off by rows of pillars. I was inspired partly by churches that have been converted for secular use, as so often happens nowadays, including in the Netherlands. Despite that change in use, the building retains a recollection of spirituality, the possibility that something supernatural could happen. That is also the case in Lohengrin. In the first act, we see a people in a bleak, grey situation hoping for a miracle.”

And that miracle, or at any rate a supernatural element, is introduced in the opera with the arrival of Lohengrin. How did you tackle that?

“The space gradually transforms and acquires a greater sense of depth. For example, the back wall changes into a wintry landscape, the round window at the top suddenly seems to take on the appearance of the sun or moon, and the light through the plastic strip curtain adds a mysterious ambience. The objects in the rather banal and depressing hall are cast in a new light, which creates scope for the magical and inexplicable elements of the story.”

As an artist, you often work with multiple layers that are revealed by a change in the point of view or the use of light. How does this approach translate to the theatre?

“In an art exhibition, visitors can view my art from different angles, which lets them see the layers in a work from the various viewpoints. In a theatre, the audience are confined to particular seats and they also have no say in how long they look at something before they are presented with the next object. I am aware of these specific circumstances and I try to work with them in my theatrical sets. In Lohengrin, I play a lot with depth and perspective, which adds layers to the set, but I also use transformations. Changes come and go on the stage. There is beauty but it is ephemeral; you can’t hold onto it. That ties in with the character Lohengrin: he shows himself to Elsa and the people, but he remains an ethereal being.”

Biology, anatomy and nature are recurring themes in your work. Do you see them in Lohengrin as well?

“What connects those themes is transiency, the inevitable confrontation with our mortality. Lohengrin’s appearance before the people is something wondrous but transitory, which is often the case in my art. One of my artworks shows a colourful, thriving nature scene, but then suddenly the light behind it is turned off and all that remains is a reflective surface, confronting the viewer with their own image. In a way, we see this same contrast in Lohengrin. After the festive mood at the end of the first act, the second act starts in a gloomy, sobering atmosphere. Ortrud and Telramund, and the audience too, find themselves in a drab reality.”

You regularly take on jobs as a set designer in addition to your work as an independent artist. What attracts you to working in the theatre?

“As an independent artist I work alone, whereas in the theatre I work in a team and I have to take numerous factors into account beyond my own profession. I find switching between these modes very inspiring, and my two practices have influenced one another over the years. Aspects such as perspective and the point of view are important in my work. Because of the theatre setting I mentioned earlier, with the audience confined to their seats, I have to explore ways of introducing transformations from a static position. The artwork has to move rather than the viewer. Another consideration is that time is experienced in a very different way in the theatre: it is predefined, rather than being determined by the spectator. Of course, the nice thing about opera is that this time is filled with the most amazing music.”

Text: Niels Nuijten

Wagner’s last Romantic opera

Wagners laatste romantische opera

Wagner’s last Romantic opera

Lohengrin, which Wagner composed between May 1846 and the end of April 1848, is the ultimate Romantic opera. It marks both the pinnacle and the end of this genre.

Its Romantic aspects reside not just in the choice of the Middle Ages as the subject matter but also – and above all – in the intermingling of the supernatural in earthly life, in the confrontation between the real world and the fantastical. In this opera, Wagner shares the Romantic view that rationalism has deprived people of their ability to make contact with everything that lies outside this world. Indeed, Lohengrin is chiefly an expression of the Romantic desire for an alternative, for something exceptional capable of transforming a world that seems empty and impoverished. However much there is this desire for the miraculous, though, Wagner is indisputably sceptical about our ability to cope with the miraculous — or the divine — in practice. His realism does not allow a happy ending.

Modern view of mankind

However, the fact that Elsa breaks the ban on asking the question is a sign not just of Wagner’s pessimism but also of his modern, liberal view of mankind. From that perspective, a life under a ban like the one Lohengrin imposes on Elsa is impossible. Elsa is simply unable to tolerate the anonymity that Lohengrin hides behind. With his prohibition, Lohengrin is demanding absolute trust, as the Holländer asks of Senta in Der fliegende Holländer. But it is more than that: the character of Lohengrin to some extent reflects Richard Wagner, an artist who saw himself as a divinely inspired genius who could therefore lay claim to absolute truth.

Eroticism and guilt

The recurring theme in Wagner’s work of the conflict between eroticism, or sexuality, and guilt seems less prominent in Lohengrin, although there is that somewhat mysterious sentence Elsa utters in the second act: “Happiness does exist without regrets”. In the opera, Elsa repeats the first part almost as an appeal. This sentence undoubtedly refers to Elsa’s relationship with Lohengrin, but it is not clear what she means specifically. What is clear is that the notion of carefree happiness is not achieved in practice; it remains a utopian dream, in line with Wagner’s sceptical view of the world.

Text: Egon Voss

Based on a translation from German into Dutch by Laura Roling

‘Cerulean silver beauty’

On Lohengrin’s composition and musical innovations

‘Cerulean silver beauty’

On Lohengrin’s composition and musical innovations

In the summer of 1845, Wagner travelled to Marienbad for five weeks with his wife, dog and parrot to ‘take the waters’. This sojourn was to have a major influence on his later work due to the reading material he brought with him. His luggage contained the poetry of Wolfram von Eschenbach, including the Parzival epic, Georg Gottfried Gervinus’ writings on the history of literature, including a discussion of the Meistersang, and the anonymous Lohengrin epic, which he found fascinating.

Wagner completed his prose outline of Lohengrin on 3 August 1845, and the final manuscript of the libretto is dated 27 November 1845. Although the opera still has ‘numbers’ and is comprised of individual arias, recitatives, choruses and scenes, Wagner makes sure they no longer stand out as such within the context of the opera as a whole. On the contrary, he seeks to integrate them comprehensively into the overarching dramatic narrative, using an approach he would later – when composing Tristan – term “the art of the transition”. [1] In Lohengrin, Wagner is thus changing course towards his ideal of a music drama that evolves from the natural prosody of speech and its intensification in dramatic declamation.

Systematic composition process

Wagner was always a very methodical composer and he used essentially the same approach right through to Parsifal, his final opera. He would note down some individual themes even while working on the libretto. Then he would start composing by putting the text to music in a continuous sketch, with the vocal line and two staves for the accompaniment. This is usually termed the ‘composition sketch’ or ‘first full draft’. Wagner started composing Lohengrin in May 1846. He made repeated changes to the text during this process. He started with Lohengrin’s exposition of the Grail in the third act, which originally consisted of two stanzas. However, he deleted the 56 bars of the second stanza for the world premiere in Weimar because the revelation of Lohengrin’s name at the end of the first stanza forms the true climax of his account. With an impeccable instinct for what works in theatre, Wagner feared the second stanza would merely have a “chilling effect”.

[1] Richard Wagner to Mathilde Wesendonck, 29 October 1859

[2] Richard Wagner to Franz Liszt, 2 July 1850

The ‘second full draft’, also known as the ‘orchestral sketch’, was an elaboration of the composition sketch in which the vocal parts were worked out in detail and the orchestral music and chorus noted down in abbreviated fashion in two systems with the treble clef and bass clef. He only composed the first version of the score proper, with the instrumentation and the details of the individual orchestral parts, in the third step. Finally, Wagner would usually produce a neat version of the score as a template for engravings and publication in print.

Reminder motifs

Lohengrin already has key ‘reminder motifs’ (Erinnerungsmotive) that presage Wagner’s later use of the leitmotif in his compositions. These motifs do not yet have the dramatic distinctiveness and melodic and harmonic flexibility of the leitmotifs in his Ring, but they still have a function that goes beyond the merely musical. In dramatic terms, they serve as a semantic signal and symbolic sound. His Lohengrin score is also the first in which Wagner did not give a metronome indication, instead allowing freedom in the choice of tempo.

From overture to prelude

Another striking novelty is that rather than an ‘overture’ — a symphonic opening to the opera introducing the main musical themes — Lohengrin has a ‘prelude’. Using a different name for the initial orchestral music draws attention to its rather different function in Lohengrin, namely as an epic introduction to the drama. No longer is there a thematic exposition such as is found in the main part of the sonata form; rather, we see a single-themed, impressionistic sonic ambience without a perceptible time signature, which unfolds in floating harmonies, and the main purpose of which is to set the emotional mood.

Thomas Mann spoke enthusiastically of the “cerulean silver beauty” of this prelude, which essentially consists of variations on a single theme in A major. [3] It starts with ‘flageolet’ harmonics played by the violins — split into eight different groups! — in the highest registers. These sparkling sounds from the ethereal Holy Grail in the blue-hued distance intensify to form a majestic climax before evaporating into the infinite, eternal space of the cosmos.

Absent from the world premiere

Wagner made slow progress with the composition of Lohengrin and was constantly interrupted by the tasks he was required to carry out as Kapellmeister in rehearsing operas. He finally finished the score on 28 April 1848. He dedicated the work to his alter ego Franz Liszt, who would eventually stand in for Wagner at the world premiere. Wagner’s involvement in the republican movement and the May Uprising in Dresden in 1849 meant he had not only rebelled against the Court of Saxony (and therefore his employer) but was also guilty of high treason. He was wanted by the Dresden police and there was a warrant for his arrest, with the threat of years in prison. Wagner fled the country with the help of Liszt and found refuge in Switzerland. It would be another twelve years before he set foot in Germany again. As a result, Wagner was not present at the world premiere of Lohengrin on 28 August 1850 in the Grand Ducal Hoftheater in Weimar, with Liszt as the conductor. Wagner first attended a rehearsal of his work only on 11 May 1861, in Vienna, remarking with a certain ironic exaggeration in a letter to Hector Berlioz that by that point he was the only German who had not yet heard Lohengrin.

[3] Thomas Mann to Emil Preetorius, 6 December 1949

Text: Sven Friedrich

Based on a translation from German into Dutch by Laura Roling

Lohengrin as an expression of Wagner’s worldview

Lohengrin als uiting van Wagners wereldbeeld

Lohengrin as an expression of Wagner’s worldview

Wagner certainly did not write himself into his dramas, but his work nevertheless undeniably reflects his life and worldview. Why else would he have written to his ‘friends’ so often and so industriously to inform them of the main considerations underlying his creative productions?

The tragedy of the Swan Knight is rooted in Wagner’s ideas about the “indignity” of the “modern world”, fuelled by the political mood in the mid-1840s and the weak response from the Prussian king, Friedrich Wilhelm IV. Wagner was in a state of “indignation at the general lovelessness”.

The solitary outsider is doomed to failure. In Lohengrin, Wagner shows that the Messianic phenomenon of a wonder is incompatible with the tangible reality of society. Wagner deliberately chooses to contrast the concept of absolute, timeless love embodied by Lohengrin with the concrete historical period, again deliberately chosen, in which the opera is set. This setting serves as an antithesis to the Vormärz, the years leading up to the 1848 March Revolution and the period in which Wagner wrote the opera. King Heinrich is to some extent an improved version of Friedrich Wilhelm IV, who sought to suppress the liberal spirit of the Hegelians rather than fostering the unity of the nation, and who concluded a Holy Alliance with the highly reactionary Tsar Nicholas I rather than fighting the “hordes from the East”.

Wagner cannot be blamed for the fact that this German nationalistic aspect of his work, which originally had a progressive dimension, was later misused to bolster imperial warmongering and Nazi terror, even if his work has been tainted by this association to this very day. In the case of Lohengrin, there is a particularly gaping chasm between the circumstances in which the opera came into being and the history of its reception.

Love and truth

Lohengrin evokes love and truth as a form of liberation. Yet the society he enters, caught up as it is in the machinations of power, is incapable of understanding love except as a calculating move. Wagner perceptively pinpoints the tragic dialectic in which Lohengrin is caught in his attempt to achieve his long-awaited goal of “being understood through love” without having to reveal his identity — in other words being loved for himself alone — through unreasonable means: the prohibition on asking questions. This is a clear symbol of the fundamental incompatibility of wondrous semblance and flawed reality. According to Wagner, it is the fate of humankind only to know love and truth in a temporally limited form. This is expressed in Elsa’s urge to ask Lohengrin to reveal his identity out of love.

Tragic loneliness

The sources only gave Wagner the outward aspects of his opera. He felt them to be “flat” and “thin”, preferring to peel away the layers of medieval material and dig down to the essence of the myth. This essence would give him the “purely human” element, with the historical “colour” merely serving as a decorative (and dramaturgically appropriate) contrast. At the heart of the Lohengrin plot, according to Wagner, is the tragic loneliness of the Swan Knight and also of the historical Elsa von Brabant, who he saw as psychologically complementary figures. His interpretation went much further than his sources, letting him express his poetic archetype of the man with his narcissistic wound that can only be healed by the unconditional love of a woman.

To clarify this, he used the allegory of the artist: “Here I encounter the most important aspect of the tragedy of the true artist’s condition with respect to modern life, the self-same condition that I expressed artistically in the material of Lohengrin: the most essential and natural desire of this artist is to be accepted from the heart and understood through feeling; and the impossibility — conditioned by modern artistic life — of finding this feeling in the impartiality and indisputable specificity that he requires in order to be understood — the force letting him communicate almost exclusively through critical comprehension rather than through feeling.”

Elsa’s brooding about Lohengrin’s nature, name and origins, which eventually leads her to ask the fateful and unavoidable question in the third act, is an expression for Wagner of the potential destructive effect of overthinking things. At the same time, this irresoluteness reflects the tragic dialectic of Elsa’s position: she must ask the question precisely because she loves Lohengrin. Her love may be all too human, but her question is driven by something much deeper than mere female curiosity. The exploration of this archetypal plot motif is an example of Wagner’s tendency towards dramatic concentration and above all his urge to give a motivation for what happens on stage.

Text: Dietmar Holland

Based on a translation from German into Dutch by Laura Roling

Programmaboek

BECOME A FRIEND OF DUTCH NATIONAL OPERA

Friends of Dutch National Opera support the singers and creators of our company. That friendship is indispensable to them, and we are happy to do something in return. For Opera Friends, we organise exclusive activities behind the scenes and online. You will receive our Friends magazine and have priority in ticket sales.