Rusalka

Performance information

Voorstellingsinformatie

Performance information

Rusalka

Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904)

Duration

3 hours and 5 minutes, including 1 interval

The performance is sung in Czech.

Dutch subtitles based on the translation by Geertrui Libbrecht.

English subtitles courtesy of Opera Vlaanderen.

Lyrical fairy tale in three acts

Makers

Libretto

Jaroslav Kvapil

Musical direction

Joana Mallwitz

Stage direction

Philipp Stölzl & Philipp M. Krenn

Set design

Heike Vollmer

Philipp Stölzl

Costume design

Anke Winckler

Choreography

Juanjo Arqués

Lighting design

Philipp Stölzl

Dramaturgy

Simon Berger

Cast

Princ (Prince)

Pavel Černoch

Cizí kněžna (Foreign Princess)

Annette Dasch

Rusalka

Johanni van Oostrum

Ježibaba

Raehann Bryce-Davis

Vodník (Water Goblin)

Maxim Kuzmin-Karavaev

Hajný (Gamekeeper)

Erik Slik

Kuchtík (Kitchen Boy)

Karin Strobos

Lesní žinky (Wood Nymphs)

Inna Demenkova*

Elenora Hu*

Maya Gour*

Lovec (Hunter)

Georgiy Derbas-Richter*

* Dutch National Opera Studio

Chorus of Dutch National Opera

Chorus master

Edward Ananian-Cooper

Dancers from Lucia Marthas Institute for Performing Arts

Part of the Holland Festival

Production team

Assistant conductor

Aldert Vermeulen

Assistant director

Meisje Barbara Hummel

Isabel Schröder

Assistant director during performances

Meisje Barbara Hummel

Directing intern

Tiara Kobald

Associate lighting design

Cor van den Brink

Rehearsal pianists

Jan-Paul Grijpink

Irina Sisoyeva

Amy Chang (Opera Studio)

Language coach

Lada Valešová

Language coach chorus

Helena Rous

Assistant chorus master

Ad Broeksteeg

Stage managers

Joost Schoenmakers

Marjolein Bergsma

Pieter Loman

Emilia Caron (intern)

Artistic planning

Margot Vervliet

Orchestra inspector

Harriet van Uden

Peter Tollenaar

Assistant stage design

Simon Schabert

Costume supervisor

Jojanneke Gremmen

Master carpenter

Edwin Rijs

Lighting manager

Ianthe van der Hoek

Props manager

Peter Paul Oort

First dresser

Sandra Bloos

First make-up artist

Frauke Bockhorn

Sound technician

Arnout Verdonk

Dramaturgy

Laura Roling

Surtitle director

Eveline Karssen

Surtitle operator

Irina Trajkovska

Set supervisor

Mark van Trigt

Production management

Edgar Lamaker

Chorus of Dutch National Opera

Sopranos

Esther Adelaar

Ineke Berends

Lisette Bolle

Else-Linde Buitenhuis

Jeanneke van Buul

Caroline Cartens

Nicole Fiselier

Melanie Greve

Oleksandra Lenyshyn

Simone van Lieshout

Tomoko Makuuchi

Sara Moreira Marques

Elizabeth Poz

Kiyoko Tachikawa

Altos

Irmgard von Asmuth

Elsa Barthas

Daniëlla Buijck

Rut Codina Palacio

Valérie Friesen

Yvonne Kok

Fang Fang Kong

Maria Kowan

Liesbeth van der Loop

Itzel Medecigo

Sophia Patsi

Marieke Reuten

Klarijn Verkaart

Ruth Willemse

Tenors

Thomas de Bruijn

Frank Engel

Milan Faas

John van Halteren

Tigran Matinyan

Richard Prada

Mirco Schmidt

François Soons

Julien Traniello

Rudi de Vries

Basses

Bora Balci

Jorne van Bergeijk

Jeroen van Glabbeek

Agris Hartmanis

Hans Pieter Herman

Dominic Kraemer

Christiaan Peters

Jaap Sletterink

René Steur

Harry Teeuwen

Dancers

Lucia Marthas Institute for Performing Arts

Dance captain

Cody Schuitemaker

Dancers

Jessy Cuello

Britt Gerrits

Amarise Jazbek

Stijn Holewijn

Tycho Lemmen

Noah Mollet

Kim Nieuwenburg

Dereck Pieter

Collin Sanders

Iris Shlomo

Noey Viereck

Ian Vrolijk

Lieke Vrugteman

Extras

Claudia Buser

Keerthi Basavarajaiah

Liza Zhukova

Evelien Emmens

Floor Scholten

Sabine van der Helm

Earl Daniel

Creso Euclydes

Renato Bertolino

Mike Wijdenbosch

Frans Dam

Johnathan Rogers

Dick Addens

Alexey Shkolnik

Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra

First violin

Liviu Prunaru

Tjeerd Top

Marijn Mijnders

Ursula Schoch

Marleen Asberg

Tomoko Kurita

Henriëtte Luytjes

Borika van den Booren

Marc Daniel van Biemen

Mirte de Kok

Junko Naito

Benjamin Peled

Nienke van Rijn

Jelena Ristic

Valentina Svyatlovskaya

Michael Waterman

Second violin

Caroline Strumphler

Anna de Veij Mestdagh

Elise Besemer

Leonie Bot

Coraline Groen

Sanne Hunfeld

Mirelys Morgan Verdecia

Sjaan Oomen

Jane Piper

Eke van Spiegel

Joanna Westers

Alessandro Di Giacomo

Caspar Horsch

Peter Brunt

Viola

Santa Vizine

Saeko Oguma

Frederik Boits

Roland Krämer

Guus Jeukendrup

Martina Forni

Yoko Wada

Edith van Moergastel

Jeroen Woudstra

Francisco Javier Rodas Sanchez

Sofie van der Schalie

Judith Wijzenbeek

Cello

Tatjana Vassiljeva-Monnier

Johan van Iersel

Benedikt Enzler

Chris van Balen

Joris van den Berg

Christian Hacker

Maartje-Maria den Herder

Boris Nedialkov

Clément Peigné

Honorine Schaeffer

Double bass

Dominic Seldis

Théotime Voisin

Rob Dirksen

Léo Genet

Felix Lashmar

Georgina Poad

Nicholas Schwartz

Olivier Thiery

Flute

Emily Beynon

Julie Moulin

Vincent Cortvrint

Oboe

Alexei Ogrintchouk

Miriam Pastor Burgos

Nicoline Alt

Clarinet

Calogero Palermo

Hein Wiedijk

Davide Lattuada

Bassoon

Andrea Cellacchi

Helma van den Brink

Horn

Katy Woolley

Laurens Woudenberg

Fons Verspaandonk

Jaap van der Vliet

Serguei Dovgaliouk

Trumpet

Omar Tomasoni

Bert Langenkamp

Jacco Groenendijk

Trombone

Bart Claessens

Raymond Munnecom

Sebastiaan Kemner

Tuba

Perry Hoogendijk

Timpani

Tomohiro Ando

Percussion

Mark Braafhart

Bence Major

Herman Rieken

Harp

Saskia Rekké

Rusalka in a nutshell

Rusalka in het kort

Rusalka in a nutshell

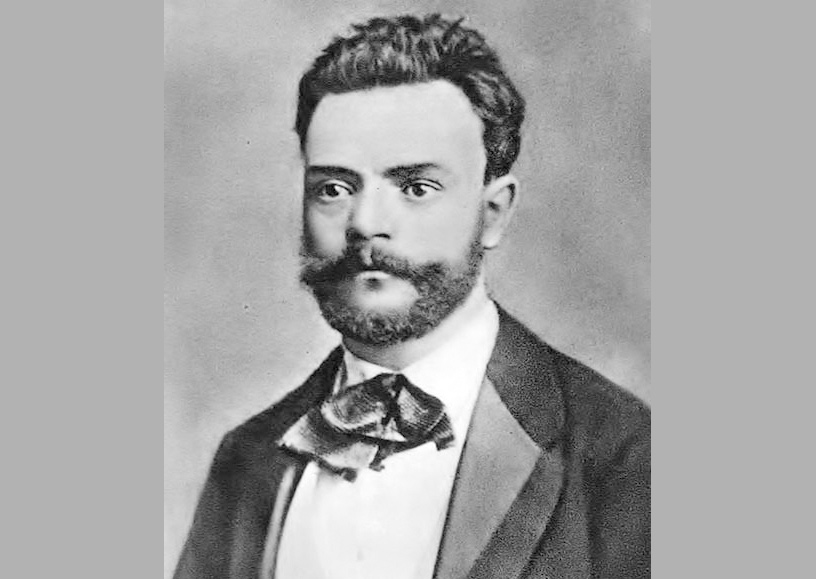

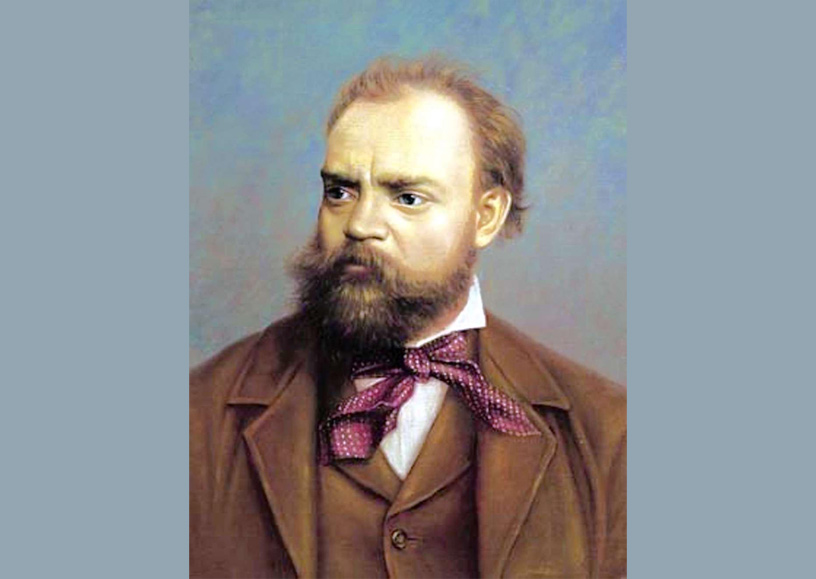

Antonín Dvořák

Composer Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904) found fame as a Czech ‘national’ composer who was able to combine Bohemian folk music with the latest developments in the international music scene. He achieved renown above all for his instrumental compositions. Rusalka is his best-known opera. It includes the popular ‘Song to the Moon’, in which Rusalka beseeches the moon to tell the man she loves that she is waiting for him. In Rusalka, Dvořák has composed exceptionally poetic and sensual music, bringing nature, nymphs and water spirits to life in a wonderfully expressive pallet of sounds.

The Little Mermaid

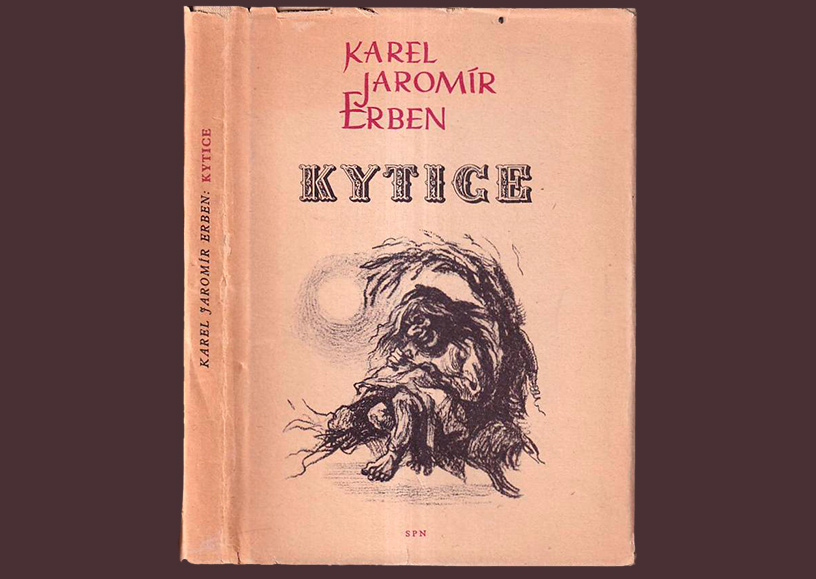

From Homer’s Odyssey to Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid, there is a long tradition of tales of water creatures who enchant men with their seductive skills, and often their beguiling singing too, luring them to their deaths — whether in revenge or otherwise. In addition to The Little Mermaid (1836) and The Sunken Bell (1896) by Gerhart Hauptmann, Rusalka’s librettist Jaroslov Kvapil also drew inspiration from Undine (1811), a novel by the German author Friedrich de la Motte-Fouqué, and the Czech fairy-tale ballads of Karl Jaromír Erben.

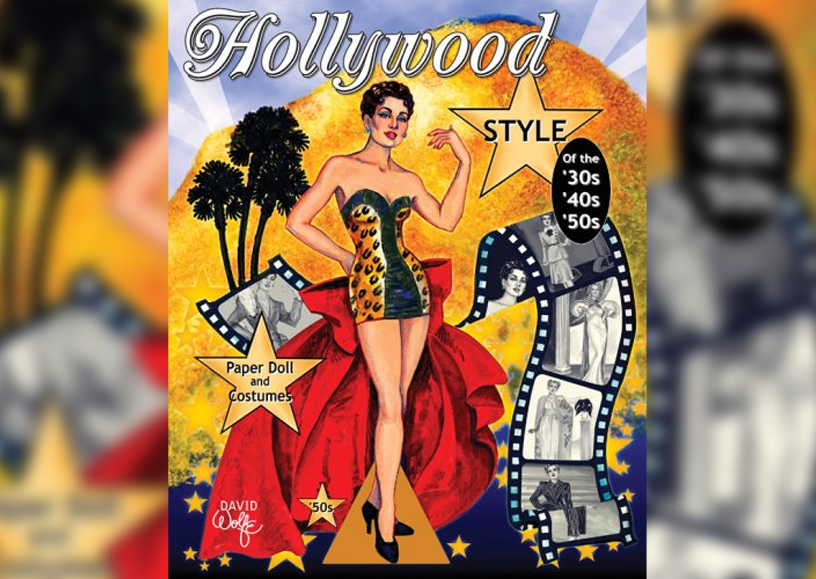

Rusalka goes to Hollywood

In the staging by the directors Philipp Stölzl and Philipp M. Krenn, there are no water spirits, fantastical woods or magical metamorphoses. Instead we see a Rusalka on the margins of society in the big city, who dreams of the world she sees on the cinema screen and would do anything to be part of it. She gets help from the witch Ježibaba, who in this version of the opera has a multifunctional hairdresser’s where customers come not just for a haircut or shave but also for far more radical procedures.

Hollywood: the dream factory

Hollywood does not just produce films: it nurtures dreams and the longing for a different life full of success and happiness in love. Film is the only bright spot in Rusalka’s life, as it was for the many people who sought sanctuary in the alternative world of Hollywood during the economic crisis of the 1930s.

Beauty

While we would like to embrace the cliché “it’s what is inside that counts”, we cannot deny the importance of external appearances. Our appearance is the visible self that others see and assume is a reflection of the invisible inner self. That is why we want so badly to be able to manipulate and control our appearance. There is now a huge industry and infrastructure only too happy to help us do that, whether it’s through diet, fashion and sport, grooming or cosmetic surgery.

The story

Follow the link below to read the story of Rusalka.

The story

I

Rusalka is sad: she is in love with a prince who is not even aware of her existence. She would do anything to meet him and become part of his world. In desperation, Rusalka turns to the witch Ježibaba, whom she begs to transform her. Ježibaba agrees, but in return Rusalka will have to lose her voice. What’s more, if she fails to win the prince’s heart she will be doomed for eternity. Rusalka agrees to the terms, and the transformation takes place. When the prince sees her, he is immediately captivated by her.

II

In the prince’s world, preparations are being made for a large celebration. The prince’s passion for Rusalka soon evaporates: he is repulsed by the coldness of her body and her silence. When a human princess arrives, it doesn’t take long for the prince to fall for her instead. He only has eyes for her and rejects Rusalka. Distraught, Rusalka leaves.

III

Rusalka is back in her own world but she no longer feels at home there either. Ježibaba appears and urges her to kill the prince. Rusalka refuses to do so. Meanwhile, the prince has come to his senses and returns to Rusalka in despair. He is full of remorse and asks her for a kiss. Rusalka warns him that it could be fatal. The prince insists — and dies in her arms.

Timeline: Antonín Dvořák

Tijdlijn

Timeline: Antonín Dvořák

8 September 1841

Antonín Leopold Dvořák is born on 8 September 1841 in Nelahozeves, a village in Bohemia (then part of Austria, now in the Czech Republic). His first violin teacher is his father, an innkeeper and butcher. By the age of five, he is playing dance tunes at the inn.

1857

In 1857, 16-year-old Dvořák moves to Prague to study at the organ school there. In the years that follow, he struggles to make a living by teaching and playing the viola in ensembles.

8 February 1863

Richard Wagner comes to Prague to conduct a concert with a selection from his oeuvre. The orchestra includes Dvořák playing the viola.

30 May 1865

On 30 May 1866, The Bartered Bride by the Czech composer Bedřich Smetana premieres in the Provisional Theatre (which later became the National Theatre). This opera goes on to become an international success and the prime example of Czech national opera. Once again, Dvořák is in the orchestra pit playing the viola.

1874

Dvořák wins the Austrian State Prize for Composition, which was set up especially for penniless musicians and is worth a substantial sum of money. The jury includes the composer Johannes Brahms, who later becomes an enthusiastic advocate of Dvořák’s music, bringing the Czech composer into contact with his good friend and publisher Fritz Simrock. Dvořák also wins the Austrian State Prize in 1876 and 1877 with his submissions.

1878

His Slavonic Dances, opus 46 (originally a piano duet, later arranged for orchestra) brings Dvořák international fame and results in various international commissions and trips. At the request of his publisher Simrock, Dvořák composes another series of Slavonic Dances, opus 72 in 1886.

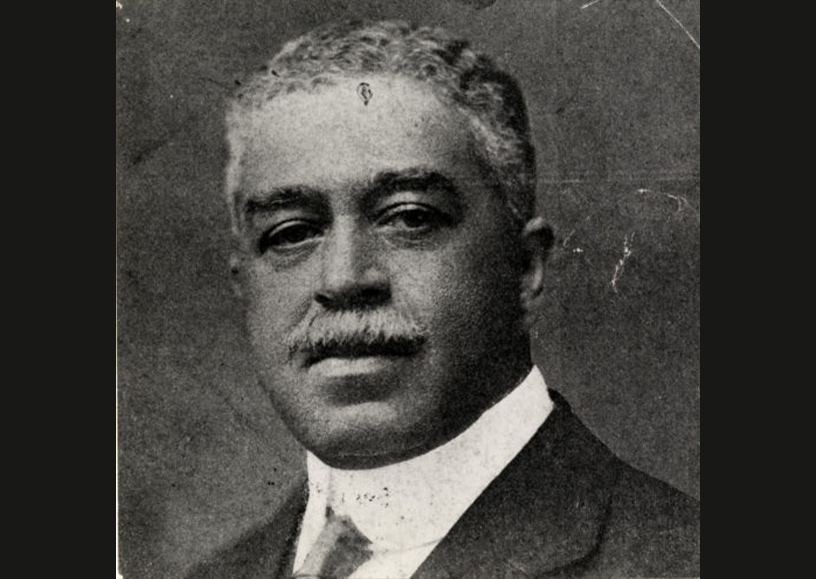

1892-1895

At the invitation of Jeanette Thurber, the founder and patron of the National Conservatory of Music, Dvořák travels to New York to head the institute. His task includes setting up a national school of music in America following the Czech model. Dvořák is convinced the musical traditions of the indigenous people and the African-American community should play an important role in that school. The Black composer Henry Burleigh introduces Dvořák to Afri- can-American spirituals.

16 December 1893

Dvořák’s Ninth symphony, ‘From the New World’, a work commissioned by the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, premieres in Carnegie Hall. The work gets an ecstatic reception and has remained part of the core symphony repertoire through to today.

1896

Dvořák composes what is known as the Erben cycle, four symphonic poems on fairy-tale-like ballads by the Czech poet Karel Jaromír Erben. One of these tone poems is entitled Vodník and tells the story of the Water Goblin, who also plays an important role in Rusalka.

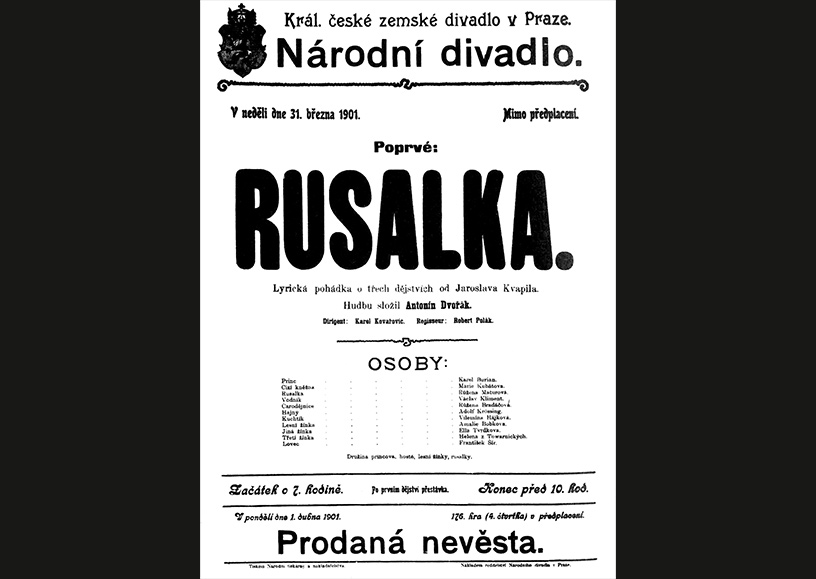

31 March 1901

Dvořák’s ninth opera, Rusalka – he wrote ten in total – premieres in the National Theatre in Prague. For a long time, Rusalka’s success is mainly limited to Czech audiences. Only in the second half of the twentieth century does the opera become popular on the international stage.

1 May 1904

Just over a month after the premiere of his tenth opera, Armida, Dvořák dies at the age of 62.

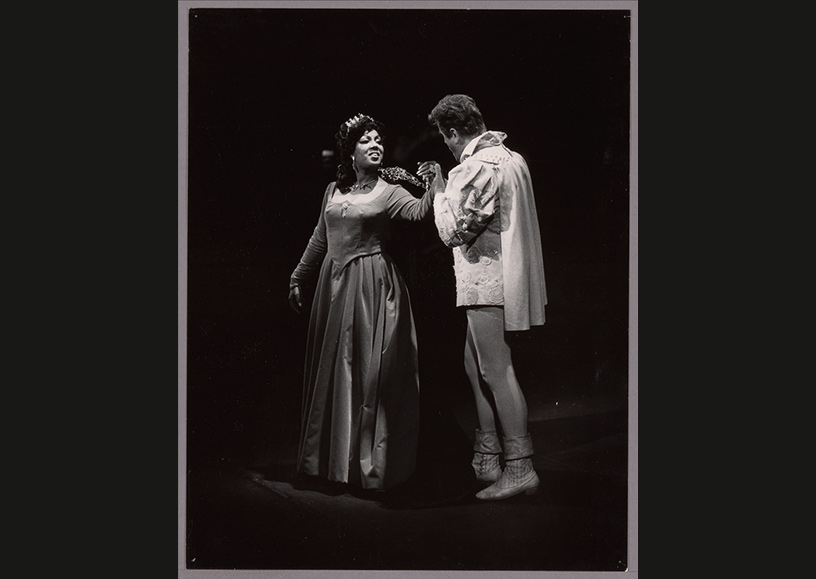

4 November 1976

Dutch National Opera presents a production of Rusalka for the first time. The conductor is Bohumil Gregor, and Václav Kaslik is responsible for the stage direction. Teresa Stratas sings Rusalka and Sir Willard White sings Vodník.

2 juni 2023

After nearly 50 years, Rusalka returns to Dutch National Opera. It is the first performance of the opera in the current theatre, Dutch National Opera & Ballet, which opened in 1986 as the Muziektheater.

Rusalka’s Hollywood dream

Follow the link below to read an interview with directors Philipp Stölzl and Philipp M. Krenn.

Rusalka’s Hollywood dream

Together, Philipp Stölzl and Philipp M. Krenn build visually impressive, incredibly detailed theatrical worlds. Their take on Dvořák’s Rusalka stays clear of water nymphs, water goblins and witches. Rather, they bring Rusalka to the seedy underbelly of New York City, presenting the story of a sex worker dreaming of a better life.

On Rusalka, you operate as a directing duo. How does this work?

Philipp Stölzl (PS): “In our collaboration, we truly complement each other. Long before the rehearsals start, we work together on building the world of the production and populating it with different characters.

Philipp M. Krenn (PK): Looking from the perspective of the audience, I think what characterises our work is the amount of attention we pay to detail. Rusalka is our main character, of course, but you will see so many other things happening on stage. We have created a detailed journey for every single character.”

When you started on this project, where did you find inspiration and what led you to the interpretation of Rusalka that we eventually see on stage?

PS: “One important source for the opera was Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid, which was closely tied to Andersen’s own unhappy love life. We know he was deeply in love with Edvard Collin, the son of his patron. Andersen’s feelings, however, were unrequited, and in 1836, when Collin got married, the heartbroken author penned his fairytale about a mermaid who sacrifices everything for love, who is willing to change even herself, to no avail. Andersen poured all his heartache into this incredibly painful story. Antonín Dvořák, in turn, brilliantly captured the essence of this fairy tale with highly hypnotic and deeply emotional music.”

“Whereas Andersen turned his real-life pain into a fairy tale, I wanted to return to the real world, and find parallels there. Who could Rusalka be in love with if she were a real person? What different worlds could the two belong to? That’s how I came up with the idea of the prince as a movie star – as someone who exists in the realm of fiction and that we, as human beings, tend to project so much of our hopes and desires on. We may think we know movie stars, they may make our hearts race, but what we know is the image they project into the world, the dream that they’re selling, not who they truly are.”

PK: “And we know that especially when times are rough, people tend to look for entertainment to provide an escape. Even during the Great Depression of the 1930s, movie-going was a very popular activity. And it’s remarkable that the popular movies of those days presented these incredibly glamorous, perfect worlds that had absolutely nothing to do with the daily lives of the people who went to see them. So it made sense to us to have our Rusalka living in poverty on the streets of New York, dreaming of Hollywood.”

In the first act, what kind of world do we find Rusalka inhabiting?

PK: “Rusalka is a lonely, poor woman in the streets of New York. She and the Wood Nymphs are sex workers, and Vodník is their pimp. He’s not just a cold-hearted pimp; it’s clear from their interaction that Rusalka is his favourite. The little money Rusalka earns, she spends on tickets to the cinema. There she finds an escape from her daily life, and she becomes fixated on going to Hollywood herself. She wants nothing more than to have this passionate, perfect relationship with the romantic lead of the films she watches. She wants her own Hollywood fairy tale.”

PS: “And Rusalka is very aware of the importance of looks. That’s why she wants to look exactly like the movie starlet in the Prince’s arms – the Foreign Princess. Even more so, Rusalka wants to physically become her. She’s very radical in that regard; it’s about having the Foreign Princess’ breasts, lips, body. So she turns to surgical intervention in order to transform into someone else. Optically, of course, she succeeds, and her looks give her access to Hollywood.”

The one helping Rusalka in her transformation is Ježibaba. What kind of character is she?

PK: “Ježibaba lives in the same neighbourhood as Rusalka, Vodník and the Wood Nymphs. She owns a shop where you can go to get a haircut or a beauty treatment, but where you can also get much more radical things done. She has a basement full of surgical equipment, and she can do anything there, from cosmetic surgery to removing bullets. You can also feel that she has seen a lot in life. At any rate, she knows that Rusalka is bound to be disappointed. Still, she is compassionate and willing to help.”

Beauty is often perceived as a thing of value, something that opens doors that otherwise remain closed. How does your staging of Rusalka reflect on this?

PS: “Beauty has always been important throughout the history of humankind, but what is a much more recent development is how radically we can influence the way we look. Over the past hundred years or so, plastic surgery has become increasingly popular and the market for it has radically increased. If you’re not born with certain looks, you can buy them up to a point. Beauty has become a commodity, and the notion has grown that with a very specific kind of beauty, you can buy happiness. Rusalka’s fatal mistake is that she falls into this trap. She hopes that by looking a certain way, she will have access to love, success and happiness.”

Your interpretation of Rusalka is situated in the late 1950s or early 1960s. Why is that?

PK: “Those were the days of Hollywood divas like Marilyn Monroe and Jayne Mansfield These actresses actually had things done, in terms of cosmetic surgery, to look a certain way and to play the part of the blonde bombshell.”

PS: “There was also an additional aura of glamour to Hollywood back then; think of films like Singing in the Rain or the Busby Berkeley films. That is the specific kind of atmosphere we wanted to capture, especially when Rusalka goes to a Hollywood film set in the second act. And that’s also where she discovers that everything she experienced in the cinema is fake. The clouds are a painted backdrop, and all the scenes require meticulous rehearsals. She used to indulge in these dreams that Hollywood produced, but now she experiences that Hollywood is, quite literally, a Dream Factory with a production line.”

In the opera, Rusalka gives up her voice. That’s why, for a significant part of the second act, she doesn’t sing. How do you treat her speechlessness?

PS: “In our production, Rusalka doesn’t stay silent because she can’t speak anymore. Rather, she is overwhelmed – shocked at the discovery that so much of it is fake. She is literally dumbstruck by the behaviour of the Prince, by the fact that he’s so different off-camera. And when she does have this emotional outburst in the second act, it’s not just Vodník who hears her, but it’s everyone on set. They stare at her and think she’s lost her mind.”

PK: “She ends up homeless in a way, not belonging to either world. She ends up in the same neighbourhood she left in the first act, but something is broken inside of her. Her old friends and colleagues don’t exactly give her a warm welcome, and she herself is also emotionally unable to return to her previous existence. It’s heartbreaking. In the final act, when we’re back on the streets, Rusalka loses her grip on reality. After she has discovered that she has given up everything for something that’s not real, the lines between fact and fiction start to become even more blurred.”

Text: Laura Roling

‘The orchestra tells us how Rusalka feels’

Follow the link below to read an interview with conductor Joana Mallwitz.

‘The orchestra tells us how Rusalka feels’

For Joana Mallwitz, the relationship between language and music is crucial to Rusalka. ‘When Rusalka is unable to speak, the orchestra tells us how she feels. The tragedy of this opera is that, while we understand her, the prince never does.’

Rusalka is generally regarded as Dvořák’s operatic masterpiece and as an example of a Czech “national” opera. What makes this work so unique?

“What we hear very clearly in Rusalka is Dvořák’s extraordinary talent for evoking elaborate fairy worlds with musical means. You can also hear it in the tone poems he wrote before Rusalka, such as The Noon Witch; as a listener you feel transported to the realm of fantasy by Dvořák’s use of motifs and orchestral colouring.”

“Furthermore, the rhythm of the Czech language and the rhythm of the music go hand in hand. A lot of Czech words have an accented first syllable, followed by a second long, unaccented syllable, and in Dvořák’s music, as a result, we often hear these typical syncopated rhythms. This is not imposed by Dvořák; rather, he follows the natural flow of the language of the libretto, which already employs the inherent musical potential of the Czech language.”

“We also know that Dvořák was very interested in the folk music and folk ballads of his native Bohemia. That’s something you can also hear very clearly in Rusalka. In the beginning of the opera, the protagonists don’t sing arias. Rather, they sing songs, with simple musical forms. Vodník sings a song, and of course there’s Rusalka’s famous ‘Song to the Moon’, with its strophes and refrain. It is only in the second act, after her transformation, that Rusalka gets to sing an aria, with its more complex musical structure.”

Before he had any success as a composer, Dvořák earned a living as a viola player. We also know that he once performed in a concert under the baton of Richard Wagner. Do we hear any specific Wagnerian influences in Rusalka?

“I think that regardless of direct, personal experience, composers at that time could not escape the influence of Wagner even if they wanted to. At the same time, however, I do feel that Dvořák did something that is very much his own. He only employs a few leitmotifs and plays with them very freely. They are very cantabile and playful. There is none of the strictness of Wagner’s use of leitmotifs.”

In the opera, we find two very different worlds; the world of nature and the human world. How are these two contrasted in the music?

“The contrast is actually not just between the world of nature and the world of humans; there’s also a dividing line that runs through the human world. On the one hand, you have the noble characters, the Prince and the Foreign Princess, who have an air of nobility to their music, and on the other hand, you have the low-born Kitchen Boy and the Gamekeeper, with their folk dance-like music.”

“But indeed, the contrast between the human and the natural worlds is clearly present. The Prince, for instance, gets to sing a very complex aria, which starkly contrasts the songs that the water creatures sing. Their music is more simple in terms of structure, but it’s also more direct and there is also an added sense of intimacy to it.”

Rusalka becomes a human being, yet she remains a stranger to the human world. How is this expressed in the opera?

“In the libretto, Rusalka is referred to as cold, and lacking in human warmth and passion. The Foreign Princess is cast as her erotic, sensual counterpart. In the music, however, things couldn’t be more different. The music of the Foreign Princess sounds very calculating. She is very much in control and aware of the effect she has on others. Rusalka’s music, however, is anything but cool. There is this incredible expressiveness and temperament to her which apparently the humans in the opera don’t see or hear, but which is always present in the music. Even when she’s unable to speak in the second act, we hear how Rusalka feels in the way her motif is present in the orchestra and how it develops, becoming ever more desperate. This motif, this very melodic lyric line is connected to her from her very first entrance in the first act, and it is skillfully used to express her inner feelings throughout the opera. When her voice is gone in the second act, the orchestra takes over and uses it to tell us what Rusalka can’t say.”

As an audience, we understand very clearly what Rusalka is feeling and trying to communicate, but somehow the Prince is unable to do so?

“It’s very poignant that there is absolutely no conversation, no dialogue between Rusalka and the Prince until the very end of the opera. It’s quite tragic, because Rusalka undergoes this transformation in order to connect with the Prince, but even when she’s visible to him, he doesn’t really see her. The two are unable to communicate, doomed to belong to two separate worlds.”

“For me, the whole story also underlines the power of words. The Foreign Princess possesses something that Rusalka doesn’t, and I don’t think it’s this passionate, erotic power. Rather, it’s the ability to speak, to wield the power of words and language, to communicate. The Foreign Princess is very eloquent, and cunning, almost like a female Iago. When Rusalka sacrifices her voice, she gives up something very powerful, which dooms her.”

Ježibaba, the witch, is the third female character of the opera. How is her character drawn musically?

“The music associated with Ježibaba exudes mystery, magic and is also a bit strange. When she’s present, you hear a lot of staccato notes, which have the effect of making you feel uncomfortable and uneasy. I also find her fascinating as a character. She leads a very autonomous life and we don’t really know what her agenda is. I feel that Rusalka, the Foreign Princess and Ježibaba in a way complement each other, almost as though they represent three sides to one woman.”

Rusalka’s ‘Song to the Moon’ is widely known. What makes this song so powerful?

“It’s one of those pieces of music that a lot of people know even without realising it. And even if they don’t, it’s very clear what the music is conveying. At the end of each line that Rusalka sings, it feels like there’s something incomplete or unfulfilled. There’s an open-endedness. And what follows after these lines is one bar of music in which the orchestra echoes or underlines Rusalka’s longing. With relatively simple means, Dvořák achieves a maximum effect. Without even understanding a word of what she’s singing, you feel that this character is missing something; that she’s longing for something.”

Rusalka is an opera of the early twentieth century. To what extent do we hear this?

“I think Rusalka was very much a modern opera when it premiered in 1901. For instance, there is this one particular motif in the opera, a repeated quick chromatic scale upwards. It sounds like a wave of water pulling Rusalka back, bubbling up from beneath, washing over her. In a way, it feels like this motif expresses Rusalka’s subconscious fears and desires. It’s interesting that Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande, also a fairytale opera, premiered just a year later in 1902. Pelléas explores the mysterious depths of the human soul. There is always so much happening beneath the surface. In its unique way, Rusalka does something similar.”

Text: Laura Roling

Programmaboek

Become a Friend of Dutch National opera

Friends of Dutch National Opera support the singers and creators of our company. That friendship is indispensable to them, and we are happy to do something in return. For Opera Friends, we organise exclusive activities behind the scenes and online. You will receive our Friends magazine and have priority in ticket sales.