Agrippina

Content

- Performance information

- In a nutshell

- The story

- Timeline: Handel in Germany, Italy and England

- Interview with director Barrie Kosky

- Rediscovering Agrippina: on the historical empress

- Revealing sounds: how the music reveals what the libretto conceals

- Interview with conductor Ottavio Dantone

- Biographies artistic team

- Biographies singers

Performance information

Voorstellingsinformatie

Performance information

Agrippina

George Frideric Handel (1685-1759)

Duration

3 hours and 55 minutes, including one interval

This performance is sung in Italian.

Dutch surtitles based on the translation by Koen van Caekenberghe. English surtitles translated by Michael Blass.

Opera in three acts (HWV 6)

Makers

Libretto

Vincenzo Grimani

Musical direction

Ottavio Dantone

Stage direction

Barrie Kosky

Set design

Rebecca Ringst

Costume design

Klaus Bruns

Lighting design

Joachim Klein

Dramaturgy

Nikolaus Stenitzer

Staging

Johannes Stepanek

Cast

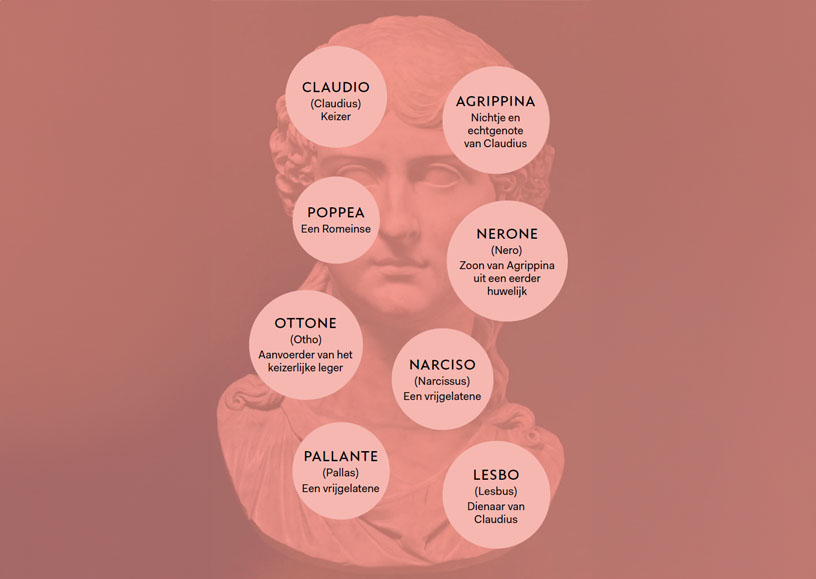

Claudio (Claudius)

Gianluca Buratto

Agrippina

Stéphanie d’Oustrac

Nerone (Nero)

John Holiday

Poppea

Ying Fang

Ottone (Otho)

Tim Mead

Pallante (Pallas)

Tommaso Barea

Narciso (Narcissus)

Jake Ingbar*

Lesbo (Lesbus)

Georgiy Derbas-Richter*

* Dutch National Opera Studio

Accademia Bizantina

Co-production with

Bayerische Staatsoper München, Royal Opera House Covent Garden London, Staatsoper Hamburg

Production team

Assistant conductor

Valeria Montanari

Assistant director

Debora Regoli

Tiara Kobald (intern)

Assistant director during performances

Debora Regoli

Rehearsal pianist

Ernst Munneke

Language coach

Marco Canepa

Stage managers

Merel Francissen

Roland Lammers van Toorenburg

Thomas Lauriks

Artistic planning

Sonja Heyl

Production management orchestra

Laura Crippa

Associate lighting designer

Benedikt Zehm

Costume supervisor

Claire Nicolas

Master carpenter

Edwin Rijs

Lighting manager

Peter van der Sluis

Lighting operator

Jasper Paternotte

Props master

Remko Holleboom

First dresser

Jenny Henger

First make-up artist

Pim van der Wielen

Sound technician

David te Marvelde

Surtitle director

Eveline Karssen

Surtitle operator

Irina Trajkovska

Head of Music Library

Rudolf Weges

Set supervisor

Mark van Trigt

Production management

Maaike Ophuijsen

Dramaturgy

Jasmijn van Wijnen

Accademia Bizantina

First violin

Alessandro Tampieri (concertmeester)

Sara Meloni

Lisa Ferguson

Maria Grokhotova

Gemma Longoni

Lavinia Soncini

Second violin

Ana Liz Ojeda

Mauro Massa

Heriberto Delgado

Gabriele Pro

Ayako Watanabe

Beatrice Scaldini

Viola

Marco Massera Alice Bisanti / Iván Sáez Schwartz (performance 15 & 17 January)

Jamiang Santi

Cello

Emmanuel Jacques* / Alessandro Palmeri* (21, 24, 26 & 28 January)

Paolo Ballanti / Daniele Lorefice (21, 24, 26 & 28 January)

Giulio Padoin

Double bass

Nicola Dal Maso*

Luca Bandini / Giovanni Valgimigli (26 & 28 January)

Flute / oboe

Fabio D’Onofrio

Rei Ishizaka

Bassoon

Alessandro Nasello

Trumpet

Manolo Nardi

Giulia Noceti

Timpani

Danilo Grassi

Lute

Simone Vallerotonda*

Harpsichord

Ottavio Dantone*

Valeria Montanari*

* basso continuo

Extras

Dick Addens

Frans Dam

Earl Daniël

Rowin Prins

Reindert van Rijn

Yonatan Stakenburg

Agrippina in a nutshell

Agrippina in het kort

Agrippina in a nutshell

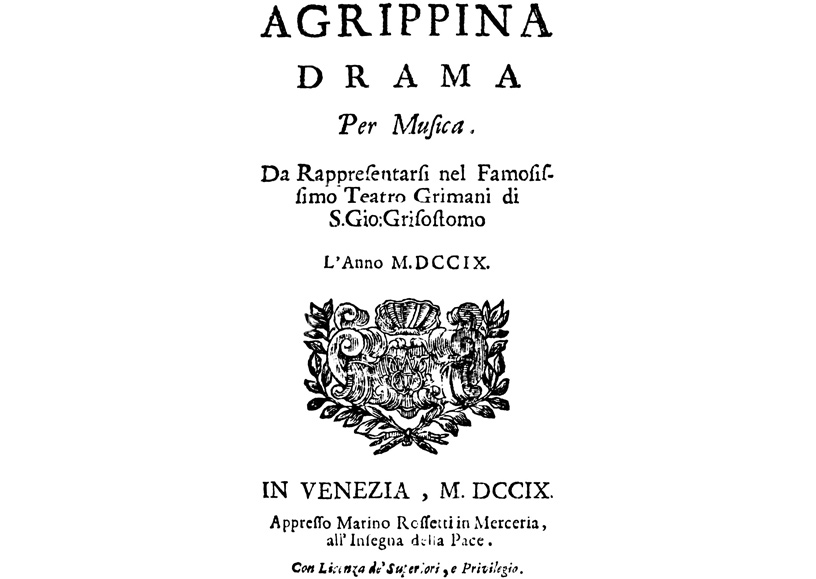

Handel’s first operatic hit

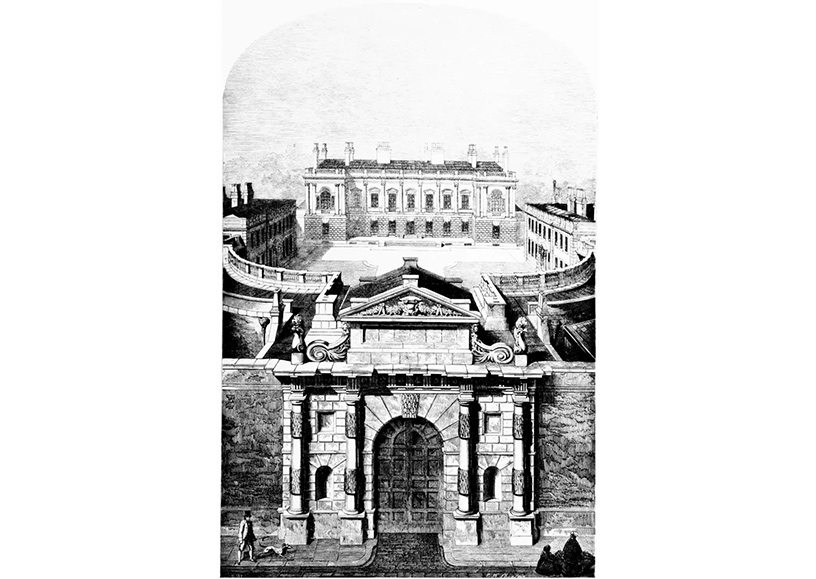

Handel was a young composer living in Italy when he wrote Agrippina. Venetian audiences went wild about the first series of performances in 1709. The theatre where Agrippina premiered, the Teatro San Giovanni Grisostomo, was owned by the Grimani family, which was why Cardinal Vincenzo Grimani put forward as the librettist for Agrippina. We will never know whether Grimani actually penned the libretto, but there is no doubt that this libretto, the only one specifically written for Handel, is one of the best Handel ever put to music.

Agrippina, an empress in love with power

Handel and his librettist based their crafty main protagonist on the historical figure Julia Agrippina. She was born in 15 CE as the daughter of Germanicus and Vipsania Agrippina. She married the emperor Claudius (who was also her uncle) and then did everything she could to put Nero, her son from a previous marriage, on the throne. That ended badly for her as that same son eventually ordered her assassination. Agrippina has gone down in history as an expert manipulator and degenerate woman.

Fascinating theatre

Tragedy and comedy complement one another perfectly in this opera, while the intermixed arias and recitatives provide the right ingredients for highly effective theatre. Like puppets in the hands of a puppet master, the characters are driven by passion and power with Agrippina steering them. Poppea shows herself to be a budding schemer too, making this opera about the hunger for power and political machinations one that centres on two female protagonists. The male characters merely react to the schemes that the women have set in motion.

A female Frank Underwood

Rather than togas and laurel wreaths, Barrie Kosky’s production has tailored suits, ties and evening dresses. “The text is so strong and the characters so diverse that this opera is asking for a modern-day setting,” says Kosky. His stage direction is inspired by series such as House of Cards, marked by its outrageous political games with plenty of black humour and clever theatrical techniques. In asides, the characters in Agrippina address the audience directly, exposing their true nature to the spectators. The music too reveals more than the libretto in the first instance. “Agrippina is a drama of simulated emotions and disguised affections, but Handel’s music repeatedly tells us the true emotional state of the characters,” writes musicologist Panja Mücke about this opera, one of Handel’s first masterpieces.

Agrippina’s end

The historical Agrippina was killed by Nero, but Handel’s opera ends before Agrippina’s death. Kosky feels the abrupt denouements so typical of the opera seria genre no longer work today, so he decided to change the final part of the opera by leaving out the intercession of the goddess Juno and concluding at the point where the masks are removed, the lights turned out and Agrippina is left alone. We see the loneliness of her victory, underlining the cynicism of her final line: “Now that Nero rules, I can die happy”.

Accademia Bizantina with Ottavio Dantone at the helm

For this series of performances of Agrippina, the conductor and harpsichordist Ottavio Dantone is bringing his own Baroque orchestra, Accademia Bizantina, to Amsterdam. Its performing practice is distinguished by its philological approach, paying attention to the codes, structures and rhetoric of the Baroque period while adapting works where necessary for modern audiences.

The story

Het verhaal

The story

I

When Agrippina, the wife of the Roman Emperor Claudio, learns her husband is dead, she knows what she has to do: make sure her son Nerone succeeds him. She persuades Pallante and Narciso, who are both in love with her, to help her and promises each individually that she will then return his love.

It transpires the Emperor is not dead after all. Ottone, the commander of the army, has rescued him. Ottone announces that he has been named Claudio’s successor as a reward for his valour. However, he admits to Agrippina that he loves Poppea more than the throne.

Agrippina uses this information in a new intrigue aimed at securing the throne for her son. She knows Claudio too has his eye on Poppea and so she tells Poppea that Ottone has betrayed her by offering her to Claudio in exchange for the imperial throne. Agrippina suggests Poppea should make Claudio jealous by convincing him that Ottone advised her to reject Claudio and return to Ottone himself instead.

II

Meanwhile, Pallante and Narciso realise they were deceived by Agrippina. They now decide to help Ottone ascend to the throne. But during a public festivity, the Emperor disparages Ottone and accuses him of betrayal. To Ottone’s dismay, everyone else rebuffs him too.

Poppea starts to have doubts about Ottone’s guilt. When they meet, she reveals what Agrippina told her and Ottone defends himself. Poppea realises she was a pawn in Agrippina’s intrigues and she swears revenge. She hatches a plot that involves her own two suitors, Claudio and Nerone.

But Agrippina continues to pursue her goal. First, she orders Pallante to murder Ottone and Narciso. Then she asks Narciso to murder Ottone and Pallante. She tells Claudio that Ottone wants to wreak revenge on him and persuades him to appoint Nerone as his successor. Impatient to be with Poppea, Claudio consents.

III

Poppea assures Ottone of her love and asks him to hide and be a silent witness to her revenge. She then receives Nerone, who she hides behind a door, followed by Claudio. Poppea persuades Claudio that he misunderstood her: Nerone is his rival, not Ottone. As proof, Poppea summons Nerone to show himself. Claudio is furious and chases off his rival in love. Poppea manages to get away from Claudio and she and Ottone swear their eternal love.

Nerone tells Agrippina what happened to him and begs her to protect him from Claudio's anger. Pallante and Narciso are so appalled by all the betrayals that they reveal Agrippina’s conspiracy to the Emperor. In the confrontation with Claudio, Agrippina realises her plans are in danger, but once again she manages to turn the situation to her advantage. She argues she was only acting in the interests of Rome and she accuses Claudio of paying too much attention to Poppea. When Agrippina tells him Ottone loves Poppea, Claudio blames Nerone, who he orders to marry Poppea. He names Ottone as his successor, but Ottone renounces the throne in order to win Poppea back. Claudio agrees to this and appoints Nerone as his heir instead. And thus in the end Agrippina achieves her dream for her son after all.

Timeline

Handel in Germany, Italy, and England

Timeline: Handel in Germany, Italy, and England

1685

George Frideric Handel is born as Georg Friedrich Händel in Halle on 23 February. He is the son of Georg Händel, a barber and surgeon in the service of the Duke of Saxe-Weissenfels, and his second wife Dorothea Taust, the daughter of a pastor.

1692

Handel spends a great deal of time hidden away in his attic room practising the clavichord, his first musical experience.

1694

The Duke of Saxe-Weissenfels hears the young Handel playing the organ and persuades him to start music lessons. He is taught the basic principles of composition and how to play the organ and harpsichord by Friedrich Zachow, the Liebfrauenkirche church organist in Halle and an outstanding teacher.

1702-1703

Handel enrols as a law student at the University of Halle. He is also an assistant organist at Halle’s Calvinist cathedral.

1703-1706

Handel ventures into the world of opera for the first time. The Hamburg opera company is unusual in the opera world of seventeenth-century Germany because it is the only company that is not part of a noble court. Handel starts his career as a second violinist. He later leads the musicians as the harpsichordist in the continuo ensemble. He is also given the opportunity to compose his first operas.

1704

Der in Krohnen erlangte Glücks-Wechsel, oder Almira, Königin von Castilien has its premiere on 8 January. It is a great success with no fewer than twenty performances. Handel’s second opera, Nero, is somewhat less successful. It is followed by Der beglückte Florindo and Die verwandelte Daphne.

1706-1710

Ferdinando de Medici, Prince of Tuscany, invites Handel to Italy. Handel visits Florence, Rome, Naples and Venice. It is Rome where he meets his first significant Italian clients, including Benedetto Pamphili. They provide him with a text in Italian and ask him to compose an allegorical cantata. The result is Il trionfo del tempo e del disinganno.

1707

Handel receives his first commission to compose an Italian opera from Ferdinando de Medici. The result, Vincer se stesso è a maggior vittoria (Rodrigo), premieres in November in the Cocomero Teatro in Florence.

1709

Handel is living in Venice. His second Italian opera Agrippina, with a libretto by the cardinal, diplomat and author Vincenzo Grimani, is a huge success. It opens doors for Handel in the international opera world.

1710

Handel is appointed Kapellmeister at the court of the Elector of Hanover. The appointment gives him scope for travelling. He goes to Düsseldorf first; then in the autumn, he pays his first visit to London.

1711

Londoners are very interested in Italian opera. Handel stages his first Italian opera, Rodrigo, in the city in an adaptation to suit London audiences. An entire cast of Italian singers is hired for the performance in the Queen’s Theatre. The opera is the hit of the season.

1712

Handel returns to London and this time he decides to stay. He spends the first three years in Burlington House, which the young Earl of Burlington has turned into a creative centre where he supports various artistic initiatives. On 22 November, Handel’s Il pastor fido has its premiere. This pastoral opera in a restrained style does not find favour with London audiences.

1713

Handel responds to this lack of success by opting for grand, heroic gestures and stunning effects in his next opera, Teseo. As was his custom in Italy, Handel composes church music in London in addition to his operas. He writes music for the Royal Chapel in St James’s Palace and composes a Te Deum and Jubilate to mark the signing of the Treaty of Utrecht.

1714

To celebrate the accession to the English throne of his former employer, the Elector of Hanover, as King George I, Handel composes a new Te Deum.

1759

On 6 April 1759, Handel attends the final performance of the season of his Messiah at Covent Garden Theatre in London. Shortly afterwards, he falls severely ill. On 14 April, he dies at his home on Brook Street in London. He is interred in Westminster Abbey on 20 April, with large crowds turning out for the occasion.

What is the taste of victory?

Nikolaus Stenitzer talks to Barrie Kosky

What is the taste of victory?

Nikolaus Stenitzer talks to Barrie Kosky

Nikolaus Stenitzer: Over the centuries, Agrippina has been depicted as a really gruesome figure: as a murderess, a schemer and a manipulator. What do you like about her?

Barrie Kosky: We have to be clear that we are dealing here with the Agrippina of Cardinal Grimani and Handel. Of course, there was also a historical Agrippina, and while we have a lot of information about her, we may never forget that all the descriptions of her were made by men, never by women. Nor do we have any details about her from her own perspective. So we never know precisely whether she was really so awful, or whether she was just a very strong woman. What are the facts? What is historically proven? And what was the product of imagination or projection? The one thing we can be certain about is that she was an incredibly complicated woman – and a woman who had to live and act in a world of men.

NS: So, a complicated woman in a positive sense?

BK: Absolutely. She’s a woman full of contradictions. She was a mother, a wife, an empress, a fighter and a schemer. She was clever and manipulative – but was she really any different from the men? We have this image of a monstrous woman, but was she more monstrous than the men around her? We just don’t know. Western history was written only by men for a very long time – especially Greek and Roman history. But of course, operas and plays about historical figures are always just theatrical variations on a theme. In our production, we’re concerned with what’s actually in the libretto and in Handel’s music; this is naturally what I have to deal with as the director. It’s only on the first day of rehearsal that we begin to find out who this Agrippina really is.

NS: The Agrippina we encounter in the opera is very successful with her intrigues and machinations. But we also see her in an anxious state, as in her Act II aria ‘Pensieri, voi mi tormentate’. What does the music tell us about this character?

BK: She is a very contradictory character. It would be pretty easy to present her on stage as a powerful woman like Joan Collins in the TV soap opera Dynasty. But the music tells us something different. It’s interesting that many of her arias are in the minor mode. In a lot of cases, we would perhaps expect a triumphal aria, or an aria depicting her rage or her desire for vengeance, in D major or C major – but there’s none of that! Instead, we hear these very peculiar arias, in minor, and often with a strange, fragile sense of emotion. Agrippina’s longest, most important aria in the work is ‘Pensieri, voi mi tormentate’ – an aria in which she is tormented by inner emotions. This offers us a key to her personality. Handel and his librettist were interested in showing not just the public Agrippina, but the private person too. And this private Agrippina is not just a power figure, not just a schemer and a murderess. Sometimes she’s uncertain, she’s afraid of the world and of her own feelings, and she has self–doubts. She also loses herself in her world of manipulation and power games.

NS: All the same, she sometimes plays these games so virtuosically that you have to wonder whether she’s actually enjoying the intrigue?

BK: I know of no other role in Handel that encompasses such a broad spectrum of inner contradictions as does Agrippina. You are not sure what’s staged and what is real with her. From a dramaturgical perspective, the first 30 minutes are fantastic – you see her with her son, then there is her manipulation of Pallante and Narciso. Then she’s alone. It’s obvious that she is toying with these men. But she does it in a way that makes you wonder: can I really be sure later on where these games begin and where they end? It would be very easy to make an opera in which Agrippina is black and white. But that is precisely what she’s not.

NS: You once said that one of the strengths of Monteverdi’s L’incoronazione di Poppea lies in the fact that its characters are multi-layered, not just black and white. The cosmos in which they exist is the same as in Handel’s Agrippina; they’re the same people, but at a different stage in their lives. Are there also similarities in how Handel and Monteverdi depict the many facets of their characters?

BK: Yes and no. There are a few differences. Above all, Agrippina is a two-woman show, with guest appearances by the men. It could almost have been written for Bette Davis and Joan Crawford. In L’incoronazione di Poppea, Monteverdi and his librettist Busenello place greater emphasis on the smaller characters. And their story naturally plays at a later date, when Poppea has already been infected by the poison of Rome. She is more cynical, more ambitious, and in her own moral cosmos, she is really just as unattractive as Nerone. In the end, they make a fantastic couple. Their story is darker and even more cynical than that of Agrippina. With Grimani there is a dark side, but what is wonderful is that the subject seems so light when paired with the music. Even though it isn’t, really. And that’s great art.

NS: There is a theory that Agrippina includes a satire on the papal court. Cardinal Grimani is assumed to have been the librettist, not least because he was the Imperial ambassador at the court of Pope Clemens XI, and Claudio is regarded as a parody of that Pope. But Agrippina and Poppea are undoubtedly at the heart of the work. What is more important in the libretto – the parody or the fascination with the women characters?

BK: I certainly believe that the work includes in-jokes for those who were in the know. But ultimately, I think that Grimani was especially interested in the women. His men are not nearly as complex in how they’re depicted. Ottone, Nerone and Claudio are all very straightforward in who and what they are. These characters are wonderfully, clearly drawn, but they don’t have the same contradictions or the complexity of Poppea and Agrippina.

NS: Poppea is corrupted in Monteverdi’s opera, but in Handel, she is still a work in progress. We get to know her at a stage in which she is really only impressed by herself. Then she learns of Agrippina.

BK: In this story, one thing that’s important is that she is totally in love with Ottone. We have developed a back story for her. She and Ottone were childhood sweethearts; it was their first great love, they are both 17 or 18. But of course, Poppea enjoys the attention of the other men. She flirts. And she’s clever. And that’s why she reacts not just to Agrippina’s intrigues, but also outdoes them very quickly. She herself comes up with a fantastic plan that culminates in the bedroom scene in Act III, where she juggles with three different men. It’s a virtuoso performance – better than everything that Agrippina comes up with. Agrippina sees this and says: ‘O God, what have I created here!’ She’s become a kind of Frankenstein’s monster. The opera is so attractive because Grimani and Handel don’t make any moral judgements. That is something wonderful that we find in the works of the Baroque. But good composers and good authors never pass judgment on their characters. Just as Shakespeare doesn’t judge Hamlet, Othello or Richard III. He lets his audience decide. He depicts seductive characters like Iago and Richard III, and wants the audience to side with them in a certain way. Richard III is a perfect example of this, and he actually talks to the audience. Just as Agrippina speaks to the audience in her asides. Richard III does terrible things, but he turns everything around again, he makes jokes and we laugh. And that’s a little like Agrippina. You think: ‘O God, I’m being seduced!’ And these moments are among the most brilliant you can experience in the theatre.

NS: We have spoken a lot here about the women characters, and about the strong women we find almost as a matter of course in 18th-century opera. But what happened afterwards?

BK: That’s a good question. In Greek theatre, it’s again the women characters who are the most interesting, even if they were played by men at the time. It’s Electra, Antigone and Clytemnestra that stick in your mind. It’s the same with Shakespeare’s women, or the women in Baroque plays and operas. There’s Mozart too – his women characters are incredible. But then something went terribly wrong. It’s difficult to say exactly when. But throughout the 19th century, women were pigeonholed – it’s as if they were shackled. There were some exceptions, of course, such as Offenbach’s operettas. His women are more emancipated, they’re ten times cleverer than the men, and everything is up for discussion. Just like in Baroque opera. But in 19th–century opera, the women are suddenly either sick, crazy, dying or all three. It’s impossible to imagine finding a woman like Agrippina in any German, Russian or French opera of the 19th century.

NS: The ideas of Romanticism played a big role in this.

BK: They did. Of course, I love a lot about the Romantics. But the way women were presented on stage changed a lot back then, and there were very few exceptions. Women in Verdi are almost all victims, while Wagner’s universe was something very individual when it came to women. And the idea that a woman can be ironic on stage was completely lost. Self-irony only returned later, in the late 19th and 20th centuries.

NS: Is self-irony an aspect that women characters in Baroque opera have in common with the 20th century?

BK: New issues and new problems naturally arose at the turn of the 20th century. There’s Freud and the femme fatale, the Rusalkas and the Salomes, the woman as a witch and the man-eating woman. But it’s interesting that in Janaček, for example, we once again find women with self-irony and humour. Even in Tchaikovsky, the way women are depicted starts to change again.

NS: Psychoanalysis first appeared in the 20th century. This brings us to Agrippina and Nerone’s strange mother-son relationship, which begs a Freudian interpretation.

BK: Yes, Nerone is an eccentric character. This is also how we get to know him from the beginning in his first, really strange and unexpected aria, where he sings about his mother with a peculiar kind of melancholy. Nerone is a complete outsider, also within the context of the opera. He’s an only child, he’s spoilt, adolescent, unformed. And extremely sexualized, perhaps even pansexual. He also has something of a cheeky Puck-like figure about him (from Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, ed.). But Handel shows us two sides of him: the melancholic arias show his completely depressive side, and the coloratura shows Nerone’s potential for madness. So we see him as a young man who ends up as a kind of manic-depressive, which is probably what the real Nero was. He was mad, but also depressive. And he was an artist – let’s not forget that, either. He loved music and literature and saw himself as an artist.

NS: Hysteria in the coloratura brings us to another element of Baroque opera that is interesting for its psychology: the da capo aria. This type of aria, with its repetitions and its A – B – A form, has been described by the Handel expert Silke Leopold as an opportunity for a character to ‘capture’ his or her emotions. After the B section offers a chance for reflection, the emotions that had erupted in the opening A section are brought back, but are now more controlled. In its time, the da capo aria was primarily an opportunity for artists to demonstrate their mastery of their art. How do you stage these arias?

BK: When I was young, I tended to try and evade this problem. But today, I find this structure magnificent. It’s a mistake to think that the da capo aria was only intended as an ornament – a chance for the singer to demonstrate his or her virtuosity. Handel was too clever for that. The action halts in the da capo arias and the temporal structure is completely different from in the recitatives. The characters leave the narrative and go inside themselves. It’s an expression of something very inner. The B section always offers a kind of ‘hang on, that’s wrong!’ moment. Or ‘No, that can’t be! – What I just sang in the A section can’t be right, wake up!’. And the decisive moment is always at the close of the B section, which leads us into the da capo. This moment is always different, but in formal terms, I think it’s fantastic. For directors working with opera for the first time, keeping to the score is often difficult – everything is fixed, and you don’t have the flexibility that you have in the spoken theatre or with new works. That’s true, of course – but still, I love this form. I love having to work with the score. The fact that you’re confronted with the architecture of the notes and that you have to work within it. And it’s just like with the da capo aria. It’s not just interesting: it’s an act of liberation for a director to be able to work with this form. But you do need opera singers who can act very well if you’re going to make your da capo arias a success. The emotionality of voice, body and character has to come from the singer–actors themselves.

NS: Another big topic when directing Baroque opera is the recitatives. In Agrippina, too, large parts of the action take place in recitative. Some of them are very long scenes. How do you deal with these?

BK: The libretto for Agrippina is superb. That’s a big advantage. The oratorios that Handel wrote in England often have very poetic, very dramatic texts, such as those by Charles Jennens, for example, or William Congreve. But in none of Handel’s Italian operas is the libretto as strong as in Agrippina. You could even stage the libretto as a play. The challenge with the recitatives is always to remind the singers that they have to use a different voice from in the arias. It makes no sense to sing the recitatives. In de repetities werk je voornamelijk aan de recitatieven. The work you do in rehearsal is with the recitatives. It’s like the Mozart-Da Ponte operas – like in Don Giovanni. You have to play with the rhythm, the dynamics, tempos, colours, accelerandos, fermatas, all these things. And it has to become clear that we are dealing with the same kind of complexity as with spoken dialogue. The characters think very quickly and you have to sing at the speed of their thoughts. That does not mean that everything has to be quick, but they have to keep the tempo going. The characters are virtuosic in their thoughts. And that finds expression in their recitatives.

NS: You’ve already mentioned the connection to current political thrillers and TV series. Are the power games we see in Agrippina something timeless?

BK: Yes, just like in all great theatre and opera. In our modern times, we arrogantly tend to think that all our problems are new. But they’re the same problems that Aeschylus, Euripides and Shakespeare wrote about, as did Moliere, Chekov, Ibsen, Strindberg and Da Ponte. These problems haven’t changed, but nor have they been solved. We are no wiser than we were 2,000 years ago. Jealousy, narcissism, power and violence exist today just like they did back then. And that’s why right from the start we decided that we wouldn’t have our Agrippina play in a world that was Baroque or set in Ancient Rome. You can do that, but the text is too good and the characters are too diverse. It’s almost crying out for contemporary references. There is nothing in Agrippina that has to be revised or adapted in order for it to function in a contemporary context. Nor is Agrippina just a woman who is ambitious for her son and is full of emotions. She uses her intellect and engages in political arguments. That is extraordinary.

NS: Had the librettist read Shakespeare?

BK: : Of course he knew his Shakespeare. And Baroque opera had scenes and techniques in common with Shakespeare that we find again in contemporary TV shows such as House of Cards, where the characters speak to the camera. These are a parte passages – asides in which the characters address the audience. That’s something that impressed me. And that series works with a lot of black humour within a monstrous political game, just as in Agrippina. I think that you only have to look at what’s happening in politics in our world today. We’re not that far removed from the monstrosities of the Roman world. Regrettably.

NS: Agrippina triumphs at the close of the opera, when she gets her son on the throne. If we can put aside for a moment what we know about the historical Agrippina: what options does she have at the end of the opera? Or after it?

BK:: The real Agrippina was killed by Nero. But let’s forget about that for a moment. We know that the world premiere ended with a sequence of different dances that might have gone on for a very long time. That was part and parcel of Carnival in Venice. But before that, everything goes very quickly: Nero becomes Emperor, Poppea and Ottone stay together and Agrippina says: ‘Now I can die happy’. That’s her last sentence in the piece. And in my production, I decided that she can’t just sing it full of joy, like a proud mother – ‘My son’s on the throne/he’s married/he’s a doctor/he’s a lawyer!’ So in our production, she says: ‘Now I can die happy’ with a big question mark. It was very important to me that we didn’t keep this very swift ending. After all that’s been constructed over these three-and-a-half hours in the theatre, I can’t just change it all quickly and without any consequences. When it’s all over, I don’t want everyone to say: ‘great’, and that’s it. I want us to be preoccupied with Agrippina at the end, but she should represent all the people who live a life like hers, with her manipulative games both public and private. It’s exhausting. And that’s what I would like to show. When she’s alone at the end, when she takes off her mask, hangs up her clothes, the lights go out and she’s alone with herself: I wanted to show the exhaustion and loneliness that comes over such a person. At the close, where dances were played in Handel’s time, we play a slow piece from his oratorio L’Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato. It stands for the question: Was it all worth it? Is she satisfied? Is that a victory? And can harmony result from it?

NS: So does your story have a moral?

BK: No. It’s a purely emotional matter. How do I feel now? What does Agrippina feel, after all this is over, after her triumph? What does victory taste like, for a human being like her? I can’t imagine that it is sweet.

Text: Nikolaus Stenitzer

Rediscovering Agrippina

On the historical empress

Rediscovering Agrippina

On the historical empress

Handel’s Agrippina is a wonderful creation. She is a sneaky manipulator, single-mindedly dedicated to her goal of putting Nero on the throne. She is an overbearing mother, an unsupportive wife, a seductress and a false friend. She is not a million miles away from the portrait of Julia Agrippina Augusta we have from the historical sources: a woman breaking every rule that bound appropriate aristocratic female behaviour in the Roman world.

Our major source for Agrippina’s life is Tacitus. Tacitus was a rich and powerful senator under the emperors Domitian, Nerva and Trajan, who wrote his Annals of the Julio-Claudians (14–68 A.D.) in around 116 A.D. His aim was to write a grand narrative of the first imperial dynasty which demonstrated to his peers that the Julio-Claudian years were the most depraved and degraded of Roman history. He imagined a perfect moral version of the Roman republic from which the imperial-era Romans had fallen, and he blamed the Julio-Claudians. At the centre of his grand narrative was Julia Agrippina Augusta, the woman who ruled Rome. In Tacitus’ story, because it is a story that he is telling, Agrippina functions as the best evidence that the Rome of the Julio-Claudians had degraded beyond saving: it was so debased that a woman was allowed to hold public power. Nothing more needed to be said.

Historical sources

Tacitus’ narrative is supplemented in the surviving historical record by a few others. Pliny the Elder was a contemporary of Agrippina’s who recorded some bits and pieces about her in his immense encyclopaedia The Natural History, and fragments survive of Cassius Dio’s Greek language history of Rome, written in about 230, in which we catch glimpses of her. The imperial freedman Suetonius wrote biographies of each of the first 12 emperors, from Julius Caesar to Domitian, and Agrippina appears in the biographies of her brother, Caligula, her uncle-husband and her son, but in decontextualized anecdotes which heavily favour the sensational and titillating over anything as boring as what actually happened.

Uncertain times

Despite an apparent abundance of writing about her, we don’t know an awful lot about significant parts of Agrippina’s life. We know that she was born in November 15 A.D. in a military town on the edge of the Rhine to her mother, Vipsania Agrippina, and her father, Germanicus. We know that she was the fourth of their children to survive infancy and that she was the first daughter to survive. Two more daughters would follow, giving Agrippina five siblings in total.

We know that by the time she was 26, all of her siblings and both her parents had been murdered. Her father was the first to die. He was an immensely popular general, the adopted son of the emperor Tiberius, and handsome to boot. When he got a fever and died in Syria, there was an empire-wide wail of grief which culminated in the governor of Syria being tried for murdering Germanicus with magic and poison. Germanicus’ wife spent the rest of her life telling everyone that Tiberius had been the true murderer. Tiberius endured Vipsania Agrippina’s hostility for 15 years before he lost patience and had her and her two eldest sons exiled and then executed for unknown crimes. Agrippina was 16 when she was orphaned, but she was already married. Her first marriage is mentioned by Tacitus as a significant event of the year 28, when Agrippina was 13 and her husband was in his 30s.

Change of fate

We can guess that Agrippina never felt safe living under the eye of the emperor who killed half her family because her only child was born exactly ten months after Tiberius breathed his last and Agrippina’s brother, Caligula, ascended to the throne. It was during his reign that Agrippina made her first active move in world politics when she apparently tried to lead a coup against him following the death of her sister Drusilla, resulting in her and her remaining sister being exiled. The details are hazy, but somehow, in 39, Agrippina ended up alone on an island in the Tyrrhenian sea, waiting to die. It was pure luck for her that Caligula died instead, a year into her exile and very bloodily at the end of several knives during a successful coup. When Claudius, Germanicus’ older brother, finally won the throne, his first act was to pardon his nieces and return them to Rome. The youngest, Livilla, was exiled again and executed for adultery with the philosopher Seneca almost as soon as she arrived, leaving Agrippina and her son the sole members of her immediate family standing. You may think you know what she did next, but you don’t. She married a guy called Passienus and vanished from the historical record for five years.

Imperial wife

It wasn’t until Claudius’ young wife Messalina was executed for treason (a story that is worthy of an opera in its own right) that Agrippina was drawn back into Roman politics and made the first step towards becoming the powerful legend she now is. Just a few months after Messalina was killed, eight years after Agrippina returned from exile, Claudius married again. On New Year’s Day 49, Claudius had incest laws changed and legally married Agrippina, his niece. He also granted Agrippina the honorific title Augusta, making her his equal in name. She began to appear in public as his partner, sitting on a throne and receiving delegations. The next year, she founded a Roman colony to commemorate the place of her birth – we now know it as Cologne. She took a very active, public role in administering the empire immediately, and a lot of men hated it.

The traditional narrative developed by Tacitus is that Agrippina used her feminine wiles and familial access to Claudius to seduce him into agreeing to marry her, while simultaneously seducing Claudius’ freedman Pallas in order to get his support. As soon as she got her marriage, she then, according to Tacitus, embarked on a ruthless campaign of murder, manipulation and evil-stepmothering to accrue power and disinherit Claudius’ son Britannicus and ensure that Nero became emperor. She undermined everything good about Rome by flaunting her power in public and defiled the Roman state in the process. In Tacitus’ telling, she demonstrated exactly why the Romans prevented women from having power even over their own property: she was cruel, capricious and selfish. These are standard Roman tropes of female behaviour and they are actually quite hard to pin on Agrippina.

Talented diplomat

When you strip away the adjectives and moralizing in the sources, what you find is a woman who was a highly talented negotiator and diplomat, who made her husband popular and resolved crises in ways that made all participants happy. In a number of ways Claudius’ reign became better because of her, but her presence was such a violation of acceptable Roman behaviour and government that no later writer cared about that. Her gender coloured everything. It transformed her diplomacy into manipulation and her executions into murders.

Agrippina and Claudius ruled comfortably as partners, Augustus and Augusta, for five years while training Nero to take the throne next. Their partnership looked happy until, on 13 October 54, Agrippina poisoned her uncle-husband with a mushroom and shoved her 19-year-old son onto the throne. An interesting thing about this story is that it appears to be true. Every emperor who died of natural causes was subject to rumours that they had been murdered, but Claudius was never subject to rumours that he died naturally. Even in contemporary sources, it is stated that Agrippina murdered him, which is quite extraordinary. The telling of what happened varies wildly across the sources, but it does seem that, for reasons unknown, Agrippina decided that she needed to make Nero emperor immediately, before he was ready, and she acted decisively.

Imperial mother

It worked. Nero’s only real competition for the throne was Britannicus, who was still a child, and he was hailed emperor at the same time as Claudius’ death was announced. It’s likely that Agrippina believed that her son would show appropriate filial piety and allow his mother to keep her role as an active Augusta, deferring to her position and experience. Unfortunately for her, the main thing Nero seems to have learnt from his mother was how to ignore traditional ideas of appropriate behaviour. Within days, he had acted to publicly marginalize his mother. Within a year, they had had a fight so furious that he almost had her executed for treason. As a testament to her impressive negotiation skills, and possibly terrifying personality, she not only managed to talk her way out of being executed, but also managed to convince Nero to give some of her friends new jobs to say sorry for threatening to execute her. Then she vanished from the historical record. For five years. Again.

The only reason we know that she was still around and annoying her son was that, in 59 A.D., he decided that the only way he could move forward with his life, divorce the wife he loathed and marry Poppea was to kill his mother. He couldn’t use the traditional imperial technique of accusing her of l èse-majesté because she was, even Tacitus begrudgingly admits, beyond reproach in her lifestyle and immensely popular. He couldn’t poison her, he found out, because she took antidotes daily. He couldn’t have her stabbed because no one in his personal army would turn against her. He was stumped, until a naval friend suggested a bizarre plan involving a collapsing boat which would tip Agrippina into the sea if they could get her on it. Nero went for it.

Murder of Agrippina

And so ensued a farcical and chilling scenario where Nero tried to kill his mum with a trick boat. Unfortunately for Nero, Agrippina was a very strong swimmer and she swam back to her villa without trouble. There she sent a message to her son to inform him of the ‘accident’. Nero panicked, believing that his mother would lead a coup against him, and resorted to a desperate plan. He sent his naval pal off to Agrippina’s villa to end her once and for all.

Agrippina was murdered as the sun came up on 20 March 59 at the age of just 43. Her son was never forgiven for his matricide and Agrippina maintained a complicated legacy in Rome. Some, like Tacitus, despised her for everything she ever did. Others, like Trajan, erected statues of her. In the end, it is Tacitus’ version of her which survived the centuries but Agrippina was a real, living breathing woman and his is just one story.

Text: Emma Southon

Revealing sounds

How the music reveals what the libretto conceals

Revealing sounds

How the music reveals what the libretto conceals

The finale of George Frideric Handel’s Agrippina (1709) presents the victory of two strong women - a victory that ought to satisfy them both. Agrippina and Poppea both get exactly what they’ve wanted since the very first bars of the opera. Agrippina’s plan was to put her son Nerone on the throne, and over the course of the opera we see that she will go to any lengths to achieve this; and Poppea reaches her own goal of marrying Ottone, who for her sake has even given up his claim to succeed Emperor Claudio.

Opera seria is well known for offering abrupt solutions to seemingly intractable conflicts (one might even say it’s notorious for it). But in Agrippina, the lieto fine is a happy ending that is strangely surprising, even in the context of this genre. The intrigues, lies, plots and embittered enmities of the characters intensify throughout and reach a climax in the final recitatives. Only when Ottone renounces the throne (in itself an incredible decision) and Nerone renounces Poppea can all the knots be swiftly untangled.

Handel’s Agrippina is unusual for its constant shifts between truth and untruth. Time and again, the characters convey their real thoughts in asides to the audience, while concealing them from their antagonists on stage (the only exception is Ottone, who is a model of sincerity throughout). This game of alternating truth and dissimulation is one of the most important features of this opera.

Historical parody

For Agrippina, Handel chose a libretto that offered the tragic and the comic in equal measure. It was presumably penned by Vincenzo Grimani, the Hapsburg Viceroy in Naples, who was both a cardinal and the Imperial Ambassador to the Holy See. Grimani and his brother were also the owners of the Teatro San Giovanni Grisostomo, the most important of Venice’s many opera houses. Agrippina tells the story of Nerone’s (Emperor Nero’s) ascent to power thanks to the brutal machinations of his mother Agrippina, as related by the Roman historians Tacitus and Suetonius. But the libretto exaggerates its characters to such an extent that the result is a historical parody. It has repeatedly been claimed that we can read Agrippina as a caricature of the Papal Court under Clemens XI, and that it is a critique of the political corruption of the Roman swamp from the perspective of the Venetian Republic. But Handel’s music remains almost completely unimpressed by the libretto’s satirical elements.

Handel clothes Grimani’s farce in the earnestness of opera seria, ennobling it with his music - with a French overture, proper da capo arias, a trio, a quartet, concise secco recitatives and a single accompanied recitative. Handel put together his score using mostly works he had already composed for other purposes between 1707 and 1709, primarily Roman cantatas and oratorios. We also find borrowings here and there from other composers, such as from Reinhard Keiser’s opera Octavia, which Handel knew from his time in Hamburg.

Handel’s breakthrough

Agrippina gave Handel his breakthrough as a composer. We may justifiably claim that it was this work that set him off on his European career. After his initial experiences composing German-language operas in Hamburg – Almira (1705), Die durch Blut und Mord erlangte Liebe, oder Nero (1705) and Der beglückte Florindo/Die verwandelte Daphne (1708) – Handel had set off for Italy in order to educate himself properly. He also used his time there to engage in extensive networking, with a view to procuring a well-paid post as Kapellmeister at a later date. To have any chance at a high-flying job, it was vital for him to garner laurels as an opera composer in Italy. His first opera in Italian was Rodrigo, an opera seria written for Florence in 1707. Two years later, Handel succeeded in becoming the first ever German composer to be commissioned to write for the first-rate theatre of San Giovanni Grisostomo in Venice – quite a coup for a composer just 24 years old. It was a golden opportunity to work with exceptional singers, and Handel made the most of it. The world premiere of Agrippina took place on 26 December 1709 and was a sensational success. It was the first work to be performed in the new Carnival season, and it chalked up a further 26 performances. In 1760, John Mainwaring wrote as follows:

“The audience was so enchanted with this performance, that a stranger who should have seen the manner in which they were affected, would have imagined they had all been distracted. The theatre, at almost every pause, resounded with shouts and acclamations of viva il caro Sassone! and other expressions of approbation too extravagant to be mentioned. They were thunderstruck with the grandeur and sublimity of his stile: for never had they known till then all the powers of harmony and modulation so closely arrayed, and so forcibly combined.” (From John Mainwaring: Memoirs of the life of the late George Frederic Handel. London: R. and J. Dodsley (1760), pp.52–3)

In the years thereafter, there were new productions of Agrippina in Naples (1713), Hamburg (1718) and Vienna (1719). Excerpts from Agrippina were also given in London from 1710 onwards, when that city became Handel’s new focus of attention (this was still before the world premiere of Rinaldo, the first opera that he composed specifically for London). If we consider that most opere serie of the 18th century were given a brief, initial run and then never performed again, Handel’s Agrippina has to be regarded as an extraordinary, Europe-wide success story – and it certainly provided a major impetus for his burgeoning career.

Agrippina: a mother to be reckoned with

If we take a closer look at the various characters in Agrippina, two strong women stand out. Agrippina is the wife of Emperor Claudio, but her actions are primarily determined by her role as mother of Nerone (though his interests in turn serve her own). This becomes unmistakeably clear in the middle of the first act, when she announces to the people that Emperor Claudio has died in a storm at sea. Thanks to her cunning stratagems, Nerone is proclaimed Claudio’s successor in the ensuing quartet (the only such ensemble in the opera). But when he ascends the throne, he does so alongside his mother. Nerone is young, inexperienced, utterly beholden to Agrippina, and merely a tool for her own assumption of power. The quartet itself reflects Agrippina’s dominance by giving her a leading musical role, and in a long, unaccompanied passage she even urges Nerone to let her lead him to the throne. His mother’s dominance was already revealed in the opera’s opening recitative, when Agrippina urged her son to seize the opportunity to become emperor. The libretto only gives Nerone a few sentences here, whereas his mother presents her arguments eloquently and at length. Handel’s musical treatment of Agrippina emphasizes her domineering nature. She and Nerone are both soprano roles, but her recitatives feature bigger leaps and are rhythmically much more varied than those of her son. What’s more, she several times interrupts him without leaving any pause for breath. This, too, is a musical means of stressing the superiority of the mother that is already intimated in the libretto.

Agrippina is an impressively clever, goal-oriented, courageous woman with staying power. She acts rationally, she becomes enraged (which goes quite against the grain for the role allotted women in the later 18th century), she moves freely between the private and the public sphere and also schemes and plots unscrupulously. Handel depicts her as a strong woman by underlining those aspects of the libretto that already suggest such an interpretation of her. This is made abundantly clear in her first aria, in the sixth scene of Act I. Agrippina has only just won over Narciso and Pallante for her intrigues, and now has a solo scene in which she contemplates her further plans. She fires herself up to the task of getting her son on the throne by any means possible, even deceit. Handel’s music accentuates her nervousness in the recitative by giving her irregular rhythms, breaking up her line with rests to give us a physical sense of her agitation and breathlessness. Agrippina’s aria ‘L’alma mia fra le tempeste’ follows, in the heroic style. She sums up her hopes with the metaphor of a ship reaching safe harbour after a storm; she means by this that she will pursue her plan to rule, despite any adversity. This da capo aria in C major is dominated by sequences and semiquavers, symbolizing the storm at sea, Agrippina’s fears and her determination to overcome them. The solo oboe has a significant role, often playing in parallel with Agrippina’s coloratura. The vocal line is initially limited in range and dominated by simple, small melodic steps in quavers, which Handel clearly intended to convey Agrippina’s assertive self-awareness. By being assigned an allegorical aria, Agrippina is here treated as would be customary for a male sovereign in opera seria of the time. Handel’s music is thus already signalling to the audience both that Agrippina is a suitable candidate to ascend the throne, and that she has confidence in her ability to do so. One might even go so far as to suggest that the composer gives Agrippina this heroic aria here in order to infer to the observant 18th-century listener how the opera is going to end.

Flexibility

Agrippina does not give up, regardless of the obstacles in her way. In fact, she is highly adaptable in how she reacts to events. An excellent example of this is Act II. After Poppea has seen through Agrippina’s deceit, the latter has to come up with a new strategy to reach her goal. In a solo scene, Agrippina admits to her doubts and begs the heavens to help her. At this moment of weakness, Handel gives us the remarkable aria ‘Pensieri, voi mi tormentate’, again with a solo oboe. The orchestra begins with a plethora of dynamic contrasts, snatches of motifs, hammered-out chords, repetitions and dotted rhythms, as if nothing wants to coalesce into a proper melody. This sounds more like an introduction to an accompanied recitative. In these few bars, Handel’s music sums up Agrippina’s indecisive emotional state in a manner both subtle and precise, even before his protagonist has uttered a single word. After three crotchet rests, the voice enters – ‘late’, and on an unaccented beat. Agrippina’s initial descending phrase on ‘Pensieri’ aptly conveys her despondency, which is emphasized by its immediate echo in the solo oboe. Handel does not give a bass line at first, thereby depriving the vocal line of any foundation and symbolizing Agrippina’s predicament. Her sense of uncertainty is restricted to these few moments of text and music, however, because the recitative that follows her aria shows how she gets a grip on herself again. This is illustrated in the music by a steady quaver rhythm in the vocal part and by larger intervallic leaps. When Pallante arrives, Agrippina is ready to embark on her next intrepid intrigue.

Agrippina also commands all the registers of deception. A lie she tells is the trigger for the entangled plot of Act I: she intimates an amorous interest in both Pallante and Narciso, promising both a political role if they help to put Nerone on the throne. Once Agrippina has done this, she lures Ottone into her orbit by promising to help him woo Poppea. There follows the singular aria ‘Tu ben degno sei del’allor’, which in both text and music offers a microcosm of Agrippina’s craft. She assures Ottone that he will soon be Emperor and the husband of Poppea; but in an aside she informs the audience of her anger at the very thought of it. Handel conveys Agrippina’s different levels of utterance – her shifts between pretence and authenticity – in a brief da capo aria accompanied only by basso continuo. It is an ‘aria parlante’, whose melodic line is declamatory in character, and which enables Handel to emphasize the contrast – already present in the libretto – between Agrippina’s lies to Ottone, and her true feelings as communicated in asides to the audience. For her ‘deception’, her vocal line is kept in its middle register, between the G above middle C and the E above that; in the two ‘aside’ sections, however, her vocal range is considerably expanded (from the E above middle C to the G an octave and a half above middle C), and Handel employs chains of coloratura triplets that create rhythmic friction against the quaver accompaniment in the bass, giving the aria a feeling of instability. Agrippina carefully controls her rage in her statements to Ottone, but it is revealed in her music when she conveys her true emotions to the audience.

Poppea: all for love

Poppea is Agrippina’s antagonist. Both her text and her music characterize her as a woman in love who has no aim other than to marry Ottone. She remains charming and gracious throughout, and is uninterested in political intrigues, though she is clearly prepared to engage in deceit in order to get what she wants. She also knows how to make full use of her beauty. Handel’s music depicts Poppea quite differently from Agrippina. At her very first appearance, she sits alone in front of her mirror, rhapsodizing about how Ottone, Claudio and Nerone have all declared their love for her. She sings a virtuoso aria, ‘Vaghe perle’, in a dance-like 3/8 metre, accompanied by the gentle sound of recorders. This aria is full of ornaments and semiquaver coloratura that demand a high degree of flexibility from the singer. Poppea’s second aria is similarly dance-like, and tells of her love for Ottone.

But after this, Handel’s musical depiction of her shifts. Poppea now embarks on a clever, courageous campaign of retaliation against Agrippina, and this dominates the second half of the opera. Her virtuoso arias ‘Fa quanto vuoi’ and ‘Se giunge un dispetto’ show us what she’s capable of. These bravura arias are awash with coloratura, sequences and energetic dotted rhythms and emphasize our impression of unbridled rage on Poppea’s part. But she only gives real expression to her anger in solo scenes – never in the presence of others. The affect expressed in music was expected to reflect the social status of the character on stage, so Poppea here follows the contemporary custom – already intimated in her text – according to which the socially ‘higher’ character has to mask his or her feelings in the presence of others. Emotional outbursts are taboo in such situations. Overall, Poppea’s aria texts display a varied spectrum of emotions, ranging from love and desire to hatred. But Handel primarily composes her arias in triple time, which means even her most intense expressions of emotion have a graceful lilt to them. Poppea can also show her unbalanced side, as in the music for her aria ‘Bel piacer’ in Act III, whose constant changes of metre are not required by the stresses of the text, but instead are used to suggest a degree of mental instability.

In line with the basic affects as categorized by René Descartes in his Les Passions de l’âme of 1649, Poppea and Agrippina are both ruled by love (for Ottone and Nerone respectively) and by hatred (towards everyone who stands in the way of their plans). The primary emotion of ‘desire’, however, seems to be of lesser importance to both of them. In Poppea, it is expressed by her yearning for Ottone, while in Agrippina it is present in its variant of ‘fear’ – the fear that her plans might be thwarted. The emotions of joy, sadness and astonishment are of secondary significance to these women, and are used only in their basic forms for purposes of characterization. The ability of both Poppea and Agrippina to experience rage is what drives the plot onwards, and Handel gives expression to this in several arias. The conflicts are only resolved when the two women end their feud. The prima and seconda donna thus exist in a dramatic balance, which is also reflected by their number of arias and by the spectrum of affects they express, and in musical terms by a similar degree of virtuosity and stylistic diversity. The roles of Poppea and Agrippina are thus equal in every sense; and this fact means that Handel to a large degree has set aside the hierarchies between singers that were usual in the opera of his time.

Ottone and others: topsy-turvy gender-bending

The male roles in this opera – Claudio, Nerone and Ottone – are completely subordinate to the women, both in the number of their arias and in the fact that they tend not to act, but only to react. Agrippina thus turns the usual gender scheme of opera seria upside down. The future Emperor Nerone – the second’uomo – is depicted as a mummy’s boy overly keen to please. His spectrum of affects remains one-dimensional and dominated almost throughout by happy emotions. Claudio submits to his dominant wife – despite being emperor and despite his victories in Britain – and he is more interested in Poppea than in politics. This is reflected in the fact that his arias primarily express love and desire.

Ottone is the prim’uomo, and is introduced as the Emperor’s saviour in a storm at sea. But he is so in love with Poppea that he renounces all claim to the throne. Ottone is already depicted in the libretto as possessed of a delicate sensibility – as a so-called eroe effeminate. Handel emphasizes this side of his character significantly, on the one hand by having the part sung as a trouser role by Francesca Vanini at the first performance, and on the other by giving Ottone scenes such as that in Act II which features the only accompanied recitative in the opera. It is one of those recitatives in which we get close up to a character as he reflects on his emotions and tells us what motivates him and how he feels. The use of an accompanied recitative is not something prompted by the verse forms of the libretto (which is the case for recitatives and arias), but is a decision taken solely by the composer. Having a recitative accompanied by the orchestra means the composer wishes to provide special musical emphasis for specific passages. In opera seria, these ‘accompagnati’ accentuate theatrical climaxes, and are often employed in solo scenes at the close of an act or scene. Handel often uses them when his prima donna or prim’uomo is engaged in reflection at a moment of great sadness. They are a means of musical intensification for dramatic moments when a character is alone, not wholly in control of himself, and no longer has to mask his true feelings.

This is precisely Ottone’s situation in the fifth scene of Act II. As a result of Agrippina’s intrigues, Claudio has withdrawn his favour from Ottone, and refuses to keep him as his heir. Everyone turns away from Ottone, even Poppea, who believes he has been unfaithful to her. Having reached his lowest point, Ottone reflects on his sufferings, plunging into self-pity at the thought of the ingratitude, infidelity and injustice of it all. He sings the aria ‘Voi ch’udite il mio lamento’, in which he gives expression to his pain at having lost both the crown and Poppea. His accompanied recitative is here notable for its semiquaver figures, its dotted rhythms in the orchestra, and for its large range and the many intervallic leaps in the vocal line. These all suggest an underlying mood of protest on Ottone’s part, but his aria is nevertheless a C minor lament par excellence, with dissonant seconds in the accompaniment and a declamatory vocal line characterized by falling intervals. His coloratura on ‘dolor’ and ‘tormento’ place the focus squarely on expressing his pain. Handel’s music here goes much further than the libretto in removing from Ottone any hint of a potential future emperor. Ottone isn’t seeking rational solutions, but is instead wallowing in suffering. Even within his aria itself, he is unable to control his emotion or transform it into an affect better suited for a man of high office. Handel’s music here reveals that Ottone is not going to be the next emperor, and instead expresses the intensity of his feelings for Poppea. It is this desire that will henceforth determine everything he does.

Agrippina is a drama of feigned emotions and dissimulated affects, but Handel’s music repeatedly tells us about the real emotional state of his characters. The closing resolution of all the opera’s conflicts is thus not so surprising after all, because the music has long hinted at it. Above and beyond the actual libretto, Handel’s music provides us with a level of narrative all of its own.

Text: Panja Mücke

Translation: Jasmijn van Wijnen

‘Music is a living art form, not archaeology’

A conversation with conductor and harpsichordist Ottavio Dantone

‘Music is a living art form, not archaeology’

A conversation with conductor and harpsichordist Ottavio Dantone

The conductor and harpsichordist Ottavio Dantone is bringing his own Baroque orchestra, the Accademia Bizantina, to Amsterdam for the performances of Agrippina at Dutch National Opera. “Baroque music has its own language,” says Dantone. According to him, the key to a successful Baroque performance lies in what he terms the ‘philological’ approach to performance, plus having a group of singers and musicians with whom he can read and write the music.

Dantone taught himself to play, read and write music from the age of eight, later coming into contact with old music and polyphony in the cathedral choir of Milan. He started studying the organ at Milan’s conservatory aged thirteen, and after teaching himself to play the harpsichord on an instrument he built himself, he continued his studies at the conservatory. For Dantone, music meant Old Music from the start.

His involvement with the Baroque orchestra Accademia Bizantina started in 1989, and in 1996 he became its chief conductor and artistic director. Together with the orchestra, he embarked on a permanent investigation of the music of the seventeenth century and the relationship between rhetoric and music based on the ‘philological’ approach. “In Baroque music, ninety per cent of the sounds you are supposed to hear are not written down in the sheet music. That’s why it is so important to know the codes, the structures and the rhetoric to be able to argue why something should sound as it does.”

To avoid having to continually reinvent the wheel, Dantone prefers to work with an orchestra that speaks the same language, a group of people with whom he can literally read and write. That orchestra is Accademia Bizantina. “It is a kind of collective. I am the conductor of course, but everyone should be able to submit carefully considered musical choices that we can all reflect on and jointly decide on the best option. We need to find the same truth using our shared language. Accademia Bizantina is like a family, as we are very close, but at the same time we are very professional in our work. I always use my own orchestra for the Baroque repertoire because you need to be so attuned to one another for that music. I rarely find myself conducting an orchestra I don’t know, and then only for performances of music that is not part of the Baroque repertoire.”

Historically informed performance practices

Dantone uses the term ‘philological’ rather than ‘historically informed’ for his approach. “The latter suggests there might be performance practices that are not historically informed, but that is not the case. When I conduct a Mahler symphony, I still study the historical information relevant to the work. Of course, what makes the performance of Baroque music sound more ‘historical’ is the instrumentation: we play on instruments from the past. That makes it easier to speak the language of the Baroque period.”

“Although the manuscript is always the starting point in my research on a work, there isn’t really such a thing in the Baroque repertoire as an ‘urtext’ or ‘original performance’. Each performance was so different that it would be historically inaccurate to work based on one specific performance. What you are left with from the various versions of a work is the language. We can never know exactly how something sounded, but what we can do is study the score and work out how something is conveyed in the music. We can investigate what emotions the composer wrote into the music and how they are communicated. Unlike in Romantic music, we are not talking about the emotions that the artist — the musician — expresses in their performance of the work; this is very much about what the composer intended in his composition. In the rhetorical performance practice of Baroque music, the musician is merely interpreting this intention. We will never be able to determine exactly what was intended but we can get close by using our knowledge of Baroque’s codes and rules to examine the work’s rhetoric and thereby arrive at the most faithful performance possible. To achieve this, I have been studying the period’s rhetoric, philosophy and history for some forty years so that I also have the non-musical tools to understand what a composer could have been aiming for. But history isn’t our only source; after all, the emotions of the past are emotions we still experience today.”

Colouring in and improvising

Using knowledge about the past to bring the music to life in the present — that’s what learning and rehearsing a Baroque opera is all about. The da capo arias (with an A-B-A structure where the A part is repeated but with ornamentation) for which Baroque opera is so famous (or notorious) and the recitatives with accompaniment give the singers and musicians huge scope for colouring in the music. “The da capo arias are often seen as unnecessary repetition, so directors view them as a challenge. But nothing could be further from the truth. The repeat of the A part was precisely to provide variation, give more depth to the emotions and revisit the original material.” They are not necessarily a vehicle for displaying the singer’s vocal skills; they have an important dramatic function too. The da capo arias involve the audience in how the character processes a situation, and the spectators hear them going through an emotional development.

“That was different in the past. The singers were the major stars of their time and had the power to do what they wanted with their arias and use them to show off. To an absurd extent: the famous castrato Caffarelli stipulated in his contracts that he would sing all his arias on horseback, regardless of whether a horse belonged in the opera or not. The balance of power is different today, which benefits the quality of the music. Now, I can work with singers to examine critically where they can best add ornamentation to their arias and prepare the embellishments carefully with them. Here too, we use a philological approach. What is Handel asking us to convey here and how can we do that as convincingly as possible? Sometimes the singers prepare their ornaments themselves, sometimes they ask me to write the ornamentation for them. To do that, I first need to get to know their voice because the ornaments need to be tailored to the particular voice type and the expressive and technical capabilities of the singer in question. That means some of the music does not exist until we get into the rehearsal room.”

Which does not mean the performance is cast in stone from that point on. Baroque music depends on a certain degree of improvisation. “Within the framework of the agreed ornamentation, the singer may still take the liberty of improvising here and there during a performance. And we improvise a lot in the orchestra, for example in the basso continuo. The basso continuo parts are not written out and can be different each evening. My concertmaster isn’t averse to a little improvisation either… That’s why I like to play the harpsichord along with the orchestra — which is standard practice for Baroque music, as they didn’t have conductors back then. It means I am genuinely making music together with the singers and musicians, and I feel more of a connection with the whole.”

An Italian Handel

“The music in Agrippina is really fresh. This opera clearly shows how Handel’s stay in Italy shaped his style of composition. We see the Italian influence in the arias, for instance, which are short and simple and have a recognisable da capo structure in keeping with the Italian conventions of that time. Yet Handel also stays faithful to his German roots in his compositions. We hear that in the orchestration and the harmony. Handel has a very clear, distinctive language of his own. What makes this opera a masterpiece is that Handel knew so well what his audiences wanted. He was a man of the theatre.”

Handel created two incredibly strong female characters in Agrippina: the eponymous Agrippina is running the show, but Poppea is a born manipulator too. “The whole opera revolves around the two female characters. That is the case in the libretto, but of course, we hear it in the music too.” They lie and feign feelings to pit the other characters against one another. However, the audience gets to see the different faces of the female characters thanks to the frequent use of asides — moments when a character turns away from the action and reveals their true thoughts and emotions to the audience. In the libretto, the asides are indicated by placing the text between brackets. Something similar happens with the music. “In general, the recitatives are accompanied by a lot of instruments: harpsichord, lute, cello and double bass. You can immediately tell the asides in the music because they have a smaller accompaniment. We only hear the lute and harpsichord accompanying the singer with short chords, which immediately lets us know we have a different modality here. Baroque music in general often makes use of two levels, where the music sends a different message to the text. For example, sad moments are combined with upbeat allegro music. That irony in the music offers directors and actors a great deal of dramatic freedom.”

New ending

But Handel was also bound by the conventions of his time. “A feature of the opera seria is the sudden happy ending (lieto fine): after hours of drama, all the problems are resolved in one recitative and a short chorus, often with the intervention of one or more gods. This was customarily done so that audiences could leave the theatre in a happy state of mind. But even in Handel’s day, audiences didn’t like those abrupt endings.”

Indeed, in his stage direction, Barrie Kosky has decided to change the opera’s finale by leaving out the intervention by the goddess Juno and finishing with a lonely Agrippina. “Kosky’s ending actually anticipates what will happen to Agrippina after the events in the opera.” She doesn’t know what awaits her, but Kosky’s direction makes clear that her victory will not bring her unadulterated joy. “We have not changed the opera apart from the final two minutes. I do think it’s important to offer modern audiences a different resolution. All that has been added to the end is a very melancholic instrumental section. As a philologist, I fully support this choice. The philological approach is concerned not just with the minor details but also with the broad lines. What might Handel have wanted to write but not have been able to because the conventions of the day prevented him? That is what philology is. Our main aim is to create a successful production, a production that works for modern audiences. Music is a living art form, not archaeology.”

Text: Jasmijn van Wijnen

Translation: Claire Wilkinson

Programmaboek

Become a Friend of Dutch National Opera

Friends of Dutch National Opera support the singers and creators of our company. That friendship is indispensable to them, and we are happy to do something in return. For Opera Friends, we organise exclusive activities behind the scenes and online. You will receive our Friends magazine and have priority in ticket sales.