Roberto Devereux

Performance information

Voorstellingsinformatie

Performance information

Roberto Devereux

Gaetano Donizetti (1797-1848)

Duration

2 hours and 40 minutes, including 1 interval

The performance is sung in Italian, with surtitles in Dutch and English

Tragedia lirica in three acts

Libretto

Salvadore Cammarano

World premiere

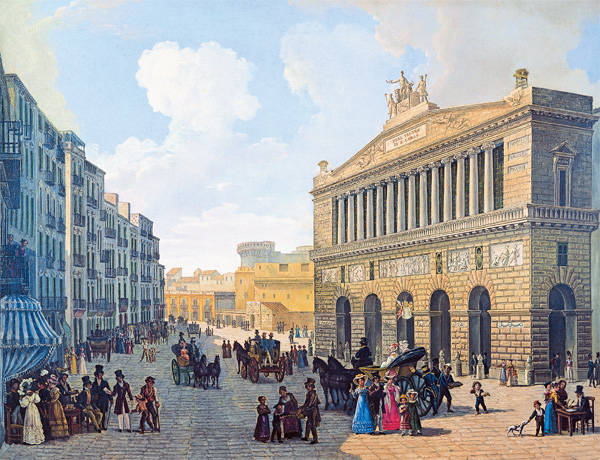

28 October 1837 Teatro San Carlo, Naples

Musical direction

Enrique Mazzola

Stage direction

Jetske Mijnssen

Set design

Ben Baur

Costumes

Klaus Bruns

Lighting design

Cor van den Brink

Dramaturgy

Luc Joosten

Elisabetta

Barno Ismatullaeva

Duca di Nottingham

Nikolai Zemlianskikh

Sara, duchessa di Nottingham

Angela Brower

Roberto Devereux

Ismael Jordi

Lord Cecil

Thando Mjandana

Sir Gualtiero Raleigh

Mark Kurmanbayev*

Un Cavaliere

Peter Arink

Un famigliare di Nottingham

Sander Heutinck

* Dutch National Opera Studio

Netherlands Chamber Orchestra

Chorus of Dutch National Opera

Chorus master

Edward Ananian-Cooper

Coproduction with

Palau de les Arts Reina Sofia, Valencia Teatro San Carlo, Naples

Production team

Assistant conductor

Stefano Sarzani

Assistant directors

Kim Mira Meyer

Annemiek van Elst

Assistant director during performances

Kim Mira Meyer

Movement coordinator

Elizaveta Zhukova

Rehearsal pianists

Peter Lockwood

Alessandro Amoretti

Language coach soloists

Alessandro Amoretti

Language coach chorus

Valentina di Taranto

Assistant chorus master

Kuo-Jen Mao

Children supervisor

Anja ten Klooster

Assistant set design

Felicia Riegel

Costume supervisor

Lars Willhausen

Master carpenter

Jeroen Jaspers

Lighting manager

Ianthe van der Hoek

Props master

Peter Paul Oort

First dresser

Jenny Henger

First make-up artist

Pim van der Wielen

Lighting operators

Jasper Paternotte

Matthijs Gulien

Video operators

Erik Vrees

Rutger Flierman

Sound technician

Florian Jankowski

Orchestra representative

Rugiero Vitalis

Surtitle director

Eveline Karssen

Surtitle operator

Maxim Paulissen

Head of the music library

Rudolf Weges

Stage management

Merel Francissen

Pieter Heebink

Sanne van de Vooren

Thomas Lauriks

Artistic planning

Emma Becker

Production manager

Nicky Cammaert

Set supervisor

Sieger Kotterer

Chorus of Dutch National Opera

Sopranos

Esther Adelaar

Lisette Bolle

Jeanneke van Buul

Caroline Cartens

Oleksandra Lenyshyn

Simone van Lieshout

Tomoko Makuuchi

Vida Matičič Malnaršič

Vesna Miletic

Sara Pegoraro

Kiyoko Tachikawa

Claudia Wijers

Altos

Elsa Barthas

Anneleen Bijnen

Rut Codina Palacio

Johanna Dur

Yvonne Kok

Fang Fang Kong

Maria Kowan

Myra Kroese

Itzel Medecigo

Sophia Patsi

Marieke Reuten

Carla Schaap

Klarijn Verkaart

Tenors

Wim Jan van Deuveren

Frank Engel

Ruud Fiselier

Cato Fordham

Livio Gabbrielli

Dimo Georgiev

John van Halteren

Stefan Kennedy

Robert Kops

Tigran Matinyan

Sullivan Noulard

Richard Prada

Julien Traniello

Jeroen de Vaal

Basses

Peter Arink

Jorne van Bergeijk

Emmanuel Franco

Julian Hartman

Agris Hartmanis

Sander Heutinck

Tom Jansen

Dominic Kraemer

Matthijs Mesdag

Maksym Nazarenko

Matthijs Schelvis

Jaap Sletterink

René Steur

Harry Teeuwen

Extras

Yannick Jhones

Alexey Shkolnik

Joy Verberk

Elizaveta Zhukova

Children

Mila Gelders

Billy Maan

Sarah Niekerk

Ella van der Vaart

Netherlands Chamber Orchestra

First violin

Joe Puglia

Tijmen Huisingh

Bartosz Woroch

Melissa Ussery

Beverley Lunt

Maaike Aarts

Kilian van Rooij

Philip Dingenen

Vanessa Damanet

Maria Rodriguez Estevez

Second violin

Bas Treub

Laura Oomens

Olga Caceanova

Siobhán Doyle

Paulien Holthuis

Maria Gilicel

Irene Nas

Catharina Ungvari

Viola

Anna Magdalena den Herder

Berdien Vrijland

Connie Pharoah

Joel Waterman

Marijke van Kooten

Giulia Wechsler

Cello

Sietse-Jan Weijenberg

Jan Bastiaan Neven

Celia Camacho Carmena

Anastasia Feruleva

Wijnand Hulst

Double bass

Annette Zahn

Joaquin Clemente Riera

Larissa Klipp

Flute

Leon Berendse

Liset Pennings

Ellen Vergunst

Oboe

Jeroen Soors

Avesta Yusufi

Clarinet

Leon Bosch

Tania Haunzwickl

Bassoon

Remko Edelaar

Dymphna van Dooremaal

Horn

Wouter Brouwer

Stef Jongbloed

Lindy Karreman

Annelies Molenaar

Trumpet

Gertjan Loot

Erik Torrenga

Trombone

Joao Mendes Canelas

Joren Elsen

Reinaldo Donoso Pizarro

Timpani

Theun van Nieuwburg

Percussion

Nando Russo

Andrea Tiddi

Gerda Tuinstra

In a nutshell

Roberto Devereux in a nutshell: about Gaetano Donizetti, Robert Devereux, and Elizabeth I

In a nutshell

The final opera in Donizetti’s Tudor Trilogy

Roberto Devereux is the final opera in Dutch National Opera’s Tudor trilogy, after Anna Bolena in 2022 and Maria Stuarda in 2023. In contrast to the previous two works, stage director Jetske Mijnssen has chosen a more modern and realistic approach for the third in the series. Queen Elizabeth I is once again the main protagonist, but rather than the strong woman facing Mary Stuart in the previous opera, we see a lonely, impotent woman at the end of her reign.

Gaetano Donizetti

Although only three years separate the composition of Maria Stuarda and that of Roberto Devereux, Donizetti creates a very different musical landscape in this opera. As conductor Enrique Mazzola explains, it is an innovative work that breaks with the rigid rules of bel canto and is in many ways a precursor of Verdi’s music drama. The tragic circumstances of Donizetti’s private life will undoubtedly have affected the creation process of this opera.

Robert Devereux, the second Earl of Essex

Robert Devereux was born in 1565. He was a great-grandson of Mary Boleyn, the sister of Queen Elizabeth I’s mother Anne Boleyn. He was a courtier and loyal officer but after being sent on a mission to Ireland in 1599, he became estranged from the Crown. In 1601, he was found guilty of high treason and beheaded in the Tower of London. In the opera, the drama centres on the love triangle between Devereux, Elizabeth and Sara Nottingham – a fictional person. The context setting the tone is the threat of execution hanging over Devereux for treason.

Elizabeth I, Queen of England and Ireland

Elizabeth I was the daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn. Her mother was executed when Elizabeth was only two years old. After the death of Henry VIII, his son Edward VI, then only nine years old, ascended the throne. Edward died not long afterwards at the age of fifteen, after which the Crown passed to Mary I. Mary died only five years after her coronation, and her half-sister Elizabeth I became queen. She would reign for forty-five years, from 1558 to her death in 1603.

The story

Robert Devereux (Roberto), long a confidant of Queen Elizabeth I (Elisabetta), has returned unexpectedly from an unsuccessful mission to Ireland. His actions raise suspicions of high treason among his political opponents. Perhaps Elisabetta’s affection for him can save him?

The story

First act

Sara, the wife of the Duke of Nottingham, is involved in an impossible relationship with her childhood sweetheart, Roberto Devereux. Elisabetta too has long cherished a passion for the young Roberto. She feels her life is worthless without him. Now she hopes to offer him protection against the death sentence hanging over him in return for him pledging his love for her. But Devereux feels unable to return her love. Nevertheless, he denies that there is a rival.

In an encounter with his old friend Roberto, the Duke of Nottingham shares his worries about his wife Sara, as well as his concerns about the trial against Devereux. Nottingham will try to protect him. That same night, Roberto meets Sara and as proof of his love for her, he gives her a ring Elisabetta had given him as a sign of her love. In return, Sara shows her love by giving him a blue scarf.

Second act

Lord Cecil informs Elisabetta of the verdict parliament has reached in Devereux’s case: he has been sentenced to death for high treason. Roberto is detained and placed under house arrest. The Queen still has to sign the death warrant. Then she learns Roberto had a blue scarf on his person when he was arrested. Elisabetta realises Roberto has a mistress, but she does not know who.

Nottingham pleads for Roberto’s life, but when he too is shown the scarf, he swears revenge. Because Roberto refuses to name his lover, Elisabetta decides to sign the death warrant. Roberto will be executed at dawn the next day.

Third act

Sara receives a letter from Roberto in which he begs her to beseech Elisabetta to spare his life and asks her to return the ring. But on her way to Elisabetta, Sara is stopped by Nottingham, who confronts her about her infidelity; she must not give the ring to the Queen.

Roberto is in his cell, facing death but hoping he will be freed at the last minute. Elisabetta is also hoping for a sign from him — she is still prepared to forgive Roberto in return for the name of her rival in love. But Lord Cecil’s arrival shows that the execution will soon take place, to Nottingham’s relief. Sara finally reaches Elisabetta with the ring and confesses that she is the rival. But it is too late. A cannon shot signals that the execution has taken place. Elisabetta is left behind desolate, her world devastated.

Timeline

Tijdlijn

Tijdlijn

1558

After a turbulent period with several monarchs in just a few years, Elizabeth I ascends to the throne of England. She becomes queen during a time of tension between the Church of England and the Roman Catholic Church, dating back to the reign of her father, Henry VIII. Elizabeth never marries, earning her the epithet ‘The Virgin Queen’.

1565

Robert Devereux is born, the son of Walter Devereux, the 1st Earl of Essex, and the noblewoman Lettice Knollys. His father dies when Robert is ten. His mother subsequently marries Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester. When Dudley dies in 1588, Robert Devereux takes over his stepfather’s political role. He holds a strong position at Court. From 1593, he is a member of the Privy Council, the highest council advising Queen Elizabeth.

1601-1603

In 1601, Robert Devereux is found guilty of high treason against the Queen and is executed in the Tower of London. Two years later, Elizabeth I dies. She is said to have spent the last years of her life plagued by loneliness and depression. The Tudor dynasty has come to an end and Elizabeth is succeeded by James I, the son of Mary Stuart.

1695

The first book is published telling the story of a possible love affair between Elizabeth I and Robert Devereux and the ring that was supposed to free him. Over time, historians have debunked the story as a myth, but it has nevertheless inspired further books and stage adaptations.

1829

The Frenchman François Ancelot writes the play Elisabeth d’Angleterre, based on a French translation of the publication from 1695.

1833

The opera Il Conte d’Essex, by the librettist Felice Romani and composer Saverio Mercadante, premieres in the Teatro Alla Scala in Milan. The work is closely based on Ancelot’s play.

1837

Roberto Devereux premieres in the Teatro di San Carlo in Naples. This is the fourth time Donizetti and Cammarano have collaborated. Like Il Conte d’Essex, the opera is based on Ancelot’s play.

1838

For the first performance in Paris, Donizetti composes an introductory Sinfonia on the theme of the English national anthem ‘God save the King/Queen’ — even though it did not yet exist in Elizabeth’s day. This version of the overture would become the one usually performed.

1840

Performances of Roberto Devereux are on the programme of the Stadsschouwburg in Amsterdam in November and December 1840. Audiences give the opera a warm reception. The performance on 4 December, promoted as a ‘Gala spectacle’, is attended by King William II and his wife Anna Paulovna.

1845-1882

During the nineteenth century, Roberto Devereux becomes one of Donizetti’s most frequently performed operas throughout Europe. However, like much of Donizetti’s oeuvre, Roberto Devereux falls out of favour at the end of the nineteenth century. The final performance is in 1882 in Pavia.

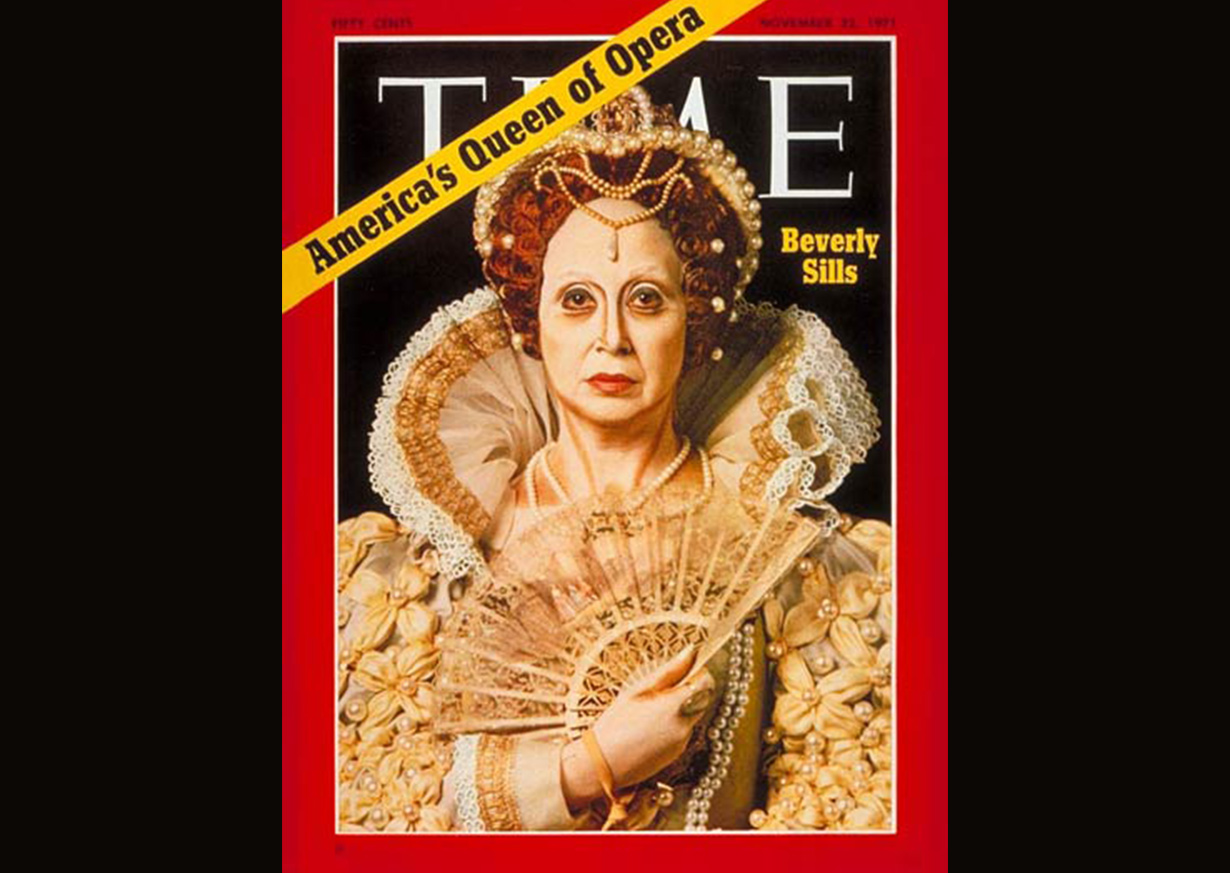

1961

The first performance of Roberto Devereux in the twentieth century takes place in 1961 in Bergamo. It is followed by a performance in Teatro di San Carlo in Naples in 1964, with Leyla Gencer as the Queen. Within a few years, that role is also played by Montserrat Caballé and Beverly Sills. Nowadays, the opera is once again part of the repertoire of various opera houses around the world, even if it is still performed less frequently than some other works by Donizetti.

Elizabeth I in a drawing-room drama

In conversation with director Jetske Mijnssen

An ‘end game’ is how Tudor trilogy director Jetske Mijnssen describes the opera Roberto Devereux. She reflects on the first two operas in the trilogy and looks ahead to the final opera.

Elizabeth I in a drawing-room drama

In conversation with director Jetske Mijnssen

How do you feel so far about your Tudor trilogy?

In January 2018, I had my first meeting with Enrique (Mazzola, ed.) and we started exchanging ideas about the trilogy. Bel canto was a completely new world for me, a world that Enrique introduced me to in his typically welcoming style. With his enormous affection for the material and knowledge of it, he opened my eyes and ears to what we would be embarking on. I see what we have been able to do in the past two seasons as a gift. For a director, it is wonderful to be able to work on a series of three productions revolving around the same theme, and to some extent with the same characters.

Looking back at the previous two operas, we started with Anna Bolena, which presents a claustrophobic world. The audience saw a historical account of a marriage that has run aground and a child who becomes irreparably damaged as a result. There was a realistic element to the way in which we told that story. In the second opera, Maria Stuarda, the audience was presented with a more surrealist world full of obsessions, with two women, each of whom had got inside the other’s head. They were haunted by one another and the tone became even more claustrophobic, especially in the final scene in the prison where Elisabetta visits Maria as if in a dream. So those two works were very different in their narrative style and expression.

How does Roberto Devereux fit in with the first two operas?

Roberto Devereux will be different again. First, I should point out that although Donizetti composed the three Tudor operas of our trilogy in the space of just seven years, he developed hugely as a composer during that time. Enrique always says you can hear the origins of Verdi in Roberto, but I would actually go further than that even. In Roberto Devereux, Donizetti breaks loose from the aesthetics of the first two operas to embrace a much more direct narrative approach. It is almost a play, a romantic thriller. We are no longer watching a queen and her courtiers; we are watching human beings.

Roberto Devereux is a masterpiece, one that in my opinion is not performed enough. As a work of theatre, it is by far the strongest of the Tudor operas. The way it builds up tension and the mood is outstanding, even in the context of Donizetti’s other works. The opera’s content is also quite different to that of the other two. That’s why we decided to go for a more modern approach for this production. We enter a present-day world with characters who deal with one another in a more direct, modern way.

Can you say something more about those characters?

This opera follows four characters. We see Roberto Devereux, the queen’s much younger lover who has betrayed her, both in love and in politics. We see the dramatic character of Sara, not only a lady-in-waiting and close companion of the queen but also Roberto’s former lover who is now caught against her will in a marriage that is on the point of collapse. She is married to the Duke of Nottingham, a true gentleman and faithful friend to Devereux who is willing to go to great lengths to defend Devereux before Parliament. He remains loyal to his wife and his queen, but his world falls apart when he discovers he has been betrayed by both his friend and his wife. And at the heart of the opera is Elisabetta, a woman who despite her age still expects so much from life and cannot bear to give up Devereux. She is prepared to forgive his treachery if he declares his love for her. That’s really quite childish — and at the same time a sign of desperation. She sees this man as her last chance of love and a life! She doesn’t want to hear of his treason; all she cares about is his love. But poor Devereux knows he cannot return her love.

Could you therefore say this opera is more about Elisabetta than about Roberto?

This opera is a real ‘end game’. We see a life falling apart, and consequently a world crumbling. Anna Bolena and Maria Stuarda both featured a main character who had all the power and was fully in control. It is different here as power is ebbing away from Elisabetta and shifting to Parliament. We see a queen who no longer holds sway to the same extent, as she herself realises. She senses an inner emptiness, which makes her latch on desperately to this final chance of love. We’ve all had that experience of falling so deeply in love with someone that you assume they must feel the same about you. But at the same time, you know deep down inside that it’s too good to be true. In a way, Elisabetta reminds me of the Marschallin in Der Rosenkavalier. She too is an older woman who clings to a much younger lover. But whereas the Marschallin eventually accepts the passing of time and lets Octavian go, Elisabetta can’t do the same with Roberto.

Could you say a few words about the costumes and sets?

While I found the historical costumes used in Anna Bolena and Maria Stuarda lovely and inspiring, my team and I felt this opera demanded a modern setting. Audiences will find themselves in an elegant, regal world. You see the preparations for a ball, an event where everyone looks superb. Except for Roberto, who is an outsider. As Elisabetta’s outfits become more and more formal, her situation becomes increasingly forlorn. The costumes become more frigid and impersonal. Elisabetta ends as an ageing, crushed woman. All the splendour we saw at the start of the opera is dismantled.

As regards the stage sets, we start in the kind of chic bedroom you might find in the series The Crown. For Elisabetta, that bedroom is a place where she feels safe, where she spends time with her ladies-in-waiting and the people close to her. But in the course of the opera, that sense of safety wanes slowly but surely. Audiences who saw the previous two operas in the trilogy may recognise parts of the decor from those productions. That is our way of showing how Elisabetta is haunted and hemmed in by her past. At the end of the opera, Elisabetta stands alone in a world that has fallen apart. Her final realisation is that her life is a failure, and at that point she loses the will to continue.

In a certain sense, this approach means we have turned Roberto Devereux into a drawing-room play where all the action takes place in an enclosed room. It is somewhat reminiscent of Chekhov, or even Pinter, where people are brought together in a confined space. By the time the curtain falls, we are looking at four people who have lost everything. Even Nottingham wonders at the end how sweet his revenge actually is. In the third act, Roberto sings two arias in succession. Interestingly, he addresses Nottingham in the first and Elisabetta in the second. It is touching to see how this man who is facing death turns to both his rival and his former lover. He asks Nottingham for forgiveness for Sara and he promises Elisabetta he will plead for her forgiveness in heaven. Roberto has given up all hope of happiness on Earth.

The whole trilogy is about people who are stuck in their lives, restricted by their obligations and their religion. These are timeless stories about human powerlessness and pain. Presenting these narratives and letting you empathise with these people is what opera is all about.

Dutch text: Maxim Paulissen

Translation: Clare Wilkinson

Notes on Donizetti’s Roberto Devereux

The ingredients for a successful opera in early nineteenth-century Italy were straightforward and clear-cut: a plot full of emotion and tension, amazing costumes, a historical setting, locations ranging from throne rooms to underground dungeons, and kings, queens, lords and brave knights who inevitably become involved in political predicaments and fatal love affairs. Add to that a large dose of eroticism, jealousy and violent revenge, plus (last but not least) music of the highest standard performed by the best, most virtuoso singers of their day.

A fatal game of power and impotency

Notes on Donizetti’s Roberto Devereux

Audiences knew exactly what they wanted and the people gathered in Teatro San Carlo in Naples on 29 October 1837 were no different in that respect. The theatre’s directors had engaged a man who, not without reason, had written to one of his librettists saying “I want love, and make it violent love”. That man was Gaetano Donizetti, who knew better than any other composer how to give the public what they wanted.

Given these circumstances, it is hardly surprising the opera Roberto Devereux was a great success. However, if you look at how the opera came about, its creation is verging on a miracle and proof of the huge intellectual and artistic will of the composer, who wrote the opera during the most wretched year of his life when he was plagued by misfortune. The accumulation of professional and personal setbacks and mishaps that Donizetti experienced during that year reinforced his usual tendency to depressive moods and probably made him particularly sensitive to the sombreness and cruelty of the Roberto Devereux libretto. When he arrived in Naples in February 1837 to put the finishing touches to the score and rehearse his new opera for the Teatro San Carlo, the city was like a morgue. By the end of June, thousands of people had died in the most devastating cholera epidemic in the city’s history. The authorities had ordered the theatres to remain closed until further notice, so there was no immediate prospect of a firm date for the premiere. What is more, Donizetti’s hopes of succeeding the recently deceased Niccolò Zingarelli as director of the renowned San Pietro alla Majella music academy were dashed soon after his arrival when the Naples-born Saverio Mercadante was appointed instead. These setbacks were a financial disaster in the rapidly changing Italian opera world where composers were ranked hierarchically far below singers, musicians, impresarios and often even set painters.

But the situation would become worse still. In June, Donizetti’s wife Virginia died of an infection shortly after the stillbirth of their youngest son. Thus Donizetti was not only deprived of professional prospects in the short term but also saw his personal plans crumbling. Without wishing to adopt the widespread sentimental clichés and romanticised images of his day, we can assume that the task of completing and rehearsing the score gave Donizetti something to hold onto in those weeks and was a source of emotional stability during this difficult period. Regardless of this biographical background, no other Italian opera has painted such a fatalistic and hopeless picture of social and moral destruction as Roberto Devereux.

England in Italian opera

The libretto was penned by Salvatore Cammarano, who also wrote Lucia di Lammermoor. Like so many Italian operas of the time, it was based on French sources, namely the drama Elisabeth d’Angleterre by Jacques Arsène Ancelot and the Histoire secrète des amours d’Elisabeth et du comte d’Essex by Jacques Lescene des Maisons, both of which had been used a few years previously by Felice Romani for the libretto of Mercadante’s opera Il conte d’Essex on the same subject. Britain was popular as a setting for Italian operas. The figure of Elizabeth I of England in particular fascinated the Romantic opera audiences of that time. Indeed, Roberto Devereux was the third of Donizetti’s operas to put this queen at the heart of the plot, following Elisabetta al castello di Kenilworth in 1829 and Maria Stuarda in 1835. This preference for the English Court as a setting was partly for pragmatic reasons of avoiding problems with the censor, but it also points to an increasing interest in presenting strong, powerful female characters on the opera stage. Moreover, as a country that had always been divided politically and split into numerous small states, Italy itself did not have historical figures with a similar status, making the famous and colourful British monarchs a logical choice of subject matter.

As in Anna Bolena and Maria Stuarda, the two previous operas in Donizetti’s ‘English trilogy’, the entanglement of political power with the egotistical interests of the rulers forms the basic conflict that drives the plot. The opera revolves around the claim the ageing Queen Elizabeth I makes on her former lover Devereux, the Earl of Essex. Following his involvement in affairs of state and the resulting accusation of high treason, Devereux finds himself dependent both politically and amorously on the Queen: if he fails to satisfy her expectations, he will die. The situation is all the more explosive because he is in a romantic relationship with Sara, the wife of his best friend the Duke of Nottingham, who is a key player in the power games too as the only person to plead Roberto’s case in the aforementioned state affair.

Politics without reason

This concept lets Donizetti refer in Roberto Devereux to the previous two operas and to standard themes in the dramatic music of the time in Italy. Yet he also goes further with a decisive step. The basic theme of Italian Romanticism, both in literature and on the opera stage, was unbridled human passion that is under threat from political arbitrariness and social oppression. Their heroic and futile rebellion against despotism and fate and the inevitable failure of dreams of self-determination and a free life gave the Romantic heroes (for example in Bellini’s operas or the historical novels of Ugo Foscolo or Alessandro Manzoni) their tragic grandeur and became their distinguishing feature — resonating particularly in the politically turbulent first third of the nineteenth century. There is a tendency in the emotional intensity and unequivocal nature of the characters towards obsessive, self-destructive behaviour, something that increasingly became the driving force in Donizetti’s dramas. This applies as well to the fact that — unlike Bellini’s Norma or Gualtiero in Il pirata — we cannot identify with characters such as Devereux or Nottingham.

Elisabetta of course, like her father Enrico (Henry VIII) in Anna Bolena, personifies the morally corrupt, arbitrary ruler who does not hesitate to use murder and torture to enforce her will. But there are no innocent victims in Roberto Devereux. The characters have their own morality and can only be understood on those terms, rather than through some external value system. For example, for understanding the plot it is completely irrelevant whether the accusations levied at Devereux are correct in a legal sense or not. When considering Roberto Devereux in the context of Donizetti’s oeuvre, it presents an almost fatalistic and hopeless view of society and history. Political power inevitably leads to abuses and arbitrariness due to mankind’s uncontrollable passions. Individual conflicts become the mirror image of political events: both develop their own dynamic that is beyond the control of reason.

Donizetti treads new paths

Of course, the musical form that the dramatic situation takes is still at the heart of the opera. At first glance, this score seems to lack the spectacular climaxes seen in other Donizetti operas. There is no fiery confrontation between two female voices as in Anna Bolena, no exquisitely melodic heartrending farewell to life as in Maria Stuarda, no large ensemble scene saturated in sound as in the first finale of Lucia di Lammermoor, and certainly nothing like the ultimate Romantic mad scene from the same opera. But Donizetti achieved a degree of unity and congruency between the emotional content and musical form beyond anything found in his other operas.

This can be illustrated by the final scenes of the second and third acts. Lasting barely twenty minutes, the relatively short second act occupies a key dramatic position in the opera’s plot and ends with an all-important clash. As so often in Donizetti’s operas, this is triggered by a fateful chance, namely Elisabetta’s discovery of a shawl Devereux had been given by Sara, his secret lover, in the finale of the first act. That the three storylines all reach a climax at the same time is crucial for the effect of this scene. This one incident simultaneously gives the three leading characters new information and changes their perspectives. Elisabetta has proof Devereux lied to her. He in turn has to give up his opportunistic hope of political advancement and erotic self-realisation. Now he finds his life is in serious danger after his mendacity comes to light, as the shawl reveals the truth to Nottingham too, changing him from a friend to the mortal enemy of the accused. Nottingham’s immediate attempt to wreak bloody revenge on Devereux is interpreted by the Queen as an expression of loyalty to his country and of personal fidelity to her. Musically, the escalating scene is designed as a sequence of three sections building up with permanent support from the instrumentation, emotional expression and tonal intensity. First there is the duet between Elisabetta and Nottingham, which expands to a trio with the appearance of Devereux and ends with a grand concertato, a spectacular ensemble piece with chorus.

Remorse comes too late

For the end of the third act, a final aria with multiple sections was composed for the prima donna. This places the ruler once again at the heart of the action in a plot that is dominated by the dynamics of historical and political processes. The remorse Elisabetta expresses at the start of the aria comes too late and the machinery of justice that was set in motion in the finale of the second act can no longer be stopped. Donizetti is unmistakeably giving a nod here to the pathetic self-aggrandizing of Romantic heroes such as Edgardo in Lucia di Lammermoor or Gennaro in Lucrezia Borgia. However, the self-pity and tearful denials have been transferred from a male leading role to a female one. By no longer formulating this outpouring of emotion as specific to one particular gender, Donizetti emphasises the universality of his understanding of history and makes clear that Elisabetta operates first and foremost as a monarch, rather than as a woman. Superficially, Nottingham may seem responsible for the death of Devereux, but in the final analysis he merely happens to be the instrument of an uncontrollable process. In this opera’s finale, Elisabetta’s ‘violent love’ thus sends those who carry out her will to their own destruction; the despotic nature and political futility of Devereux’ death sentence are clear.

Text: Fabian A. Stallknecht

We talk to the conductor Enrique Mazzola

Conductor Enrique Mazzola on Roberto Devereux and the evolution of Donizetti’s style.

The singer dictates the tempo

We talk to the conductor Enrique Mazzola

Roberto Devereux is the final opera in what is customarily called the Tudor trilogy. What place does this opera have in Donizetti’s oeuvre?

There was no Tudor trilogy as far as Donizetti was concerned. He wrote other operas as well that deal with the history of the Tudors, but in the repertoire we tend to focus on Anna Bolena, Maria Stuarda and Roberto Devereux. Donizetti himself never thought of combining these three works. He received separate commissions from different opera houses in Italy to compose individual operas, with possible librettos proposed to him. At a certain point, he decided he wanted to turn the drama of Roberto Devereux into music. It is interesting how the three operas in the trilogy all feature Elizabeth I (Elisabetta in the operas, ed.) in some form or other, but never as the title role. In Roberto Devereux, Elisabetta’s vocal part is extremely important — I would say that in a way she is the counterpart to the tenor role, making her one of the principal roles.

Can we trace an evolution in Donizetti’s approach to composition in the three operas?

Yes, definitely. Donizetti evolved considerably after Anna Bolena, not just as a composer but also as a theatre maker and emotionally. Even if you just look at the length of the operas, you see changes. Donizetti was still quite young when he wrote Anna Bolena, and he had yet to prove his skills as a composer. In this opera, he composed lengthy recitatives and arias, along with extensive choral passages. So he was very expansive in his composition, making Anna Bolena a relatively long opera, the longest of the three. If we look at Maria Stuarda and then Roberto Devereux, we see the style becoming somewhat ‘dryer’. The recitatives are shorter and very direct. The dynamic markings in the music are kept to a minimum, and so you could say they too are ‘dryer’. This change in style is undoubtedly a result of the fact that Donizetti no longer had to persuade the world of Romantic music in Italy: “Look, I’m a new composer with amazing ideas”. He was already a known name by that point; now he was famous, and so he started writing what he wanted to write rather than what he was expected to write.

Does that mean the vocal parts in Roberto Devereux are less demanding?

No, not at all. Roberto Devereux is not an easy opera for singers, with the most challenging role being that of Elisabetta. Donizetti presents her as a complex character. I think he wanted to translate that complexity into an equally intricate vocal line. So at times you have wonderful cantabile passages, but that line is frequently interrupted by jumps in the intervals: octaves, sevenths, ninths, unexpected intervals.

That means the soprano needs to master the lower register as well; she has to be able to shift to the middle register in a fraction of a second, and move up an octave to the high register a fraction later. Donizetti’s composition really adds to that complexity in Elisabetta, for example through what he does with the rhythm: rather than being tight and straightforward throughout, it is full of syncopation, stops and surprises.

This opera also stands out for the many incidences of acceleration or changes in tempo. That is quite different to the notion of bel canto as a style known for its fixed rhythm. In bel canto, you generally get a steady adagio, or a faster passage, for example an allegro vivace, but always with a constant tempo. But in this opera Donizetti accelerates the tempo — accelerandi — in a lot of places, sometimes speeding up in slow passages. It feels like a kind of mania in the thought process of the characters.

You could say it is a typically Italian form of communication. Italians do that in conversation: after a few seconds of reflection and speaking slowly, they have a flash of insight and suddenly speed up. That is so nice, and Italians love it. I had the opportunity to consult the facsimile of Donizetti’s original manuscript and it was striking to see how often the composer wrote “affrettando” (hastily) or “accel.”, short for accelerando (speeding up). That contravenes the bel canto tenet that says you should have a constant, steady pulse. So he is beginning to break the rules.

Can you tell us some more about the importance of tempo in bel canto?

You could say that in bel canto, the tempo resides with the singer: the singer dictates the tempo. We haven’t yet reached a period where you have the flowing tempo of the kind we find in Puccini’s Bohème, for example Mimi’s aria “Mi chiamono Mimi”, where you can speed up or slow down a little in response to how you feel; that is typical of Puccini. You couldn’t take such liberties in Donizetti’s day. That was partly due to the fact that it was much harder to keep everyone together musically. The conductor in the modern sense of the word had yet to be invented. So you may wonder how they still managed to make music together. Well, firstly the singer dictated the tempo. The singer had a major responsibility in indicating the pace of the music. We see that reflected in the score: the vocal numbers often start on an upbeat and that partial bar determines the tempo. The singer then probably looked at the principal violinist, a ‘primo violino’, the orchestral member we call the concertmaster these days. Rather than facing a conductor or the audience, this concertmaster was watching the singer constantly to keep in time with them. Sometimes there would be a ‘Maestro al Cembalo’, which translates literally as ‘master or leader at the harpsichord’. Of course, they weren’t actually playing a harpsichord; they were the person who rehearsed with the singers and orchestra, but they also took the tempo from the singers. So you didn’t have a conductor like you do nowadays who says, “Everyone has to keep to this tempo, this is the aesthetic result I’m aiming for, this is my vision.” That explains my initial surprise at the many instances of accelerando phrasing, because it must have been incredibly difficult in those circumstances to keep everyone together. In all probability, the singers had to be extremely clear. Perhaps they had to spend more time and effort rehearsing this too.

Could you call the musical score for Roberto Devereux innovative?

We can certainly see strong signs of Donizetti’s development in the art of composition in Roberto Devereux. He wanted to break with the strict rules of composition, and he set an example that would later be repeated by Giuseppe Verdi, whose long journey as a composer also started with unreserved acceptance of the rules of bel canto, only to subsequently break them one by one. Just as Donizetti does in Roberto Devereux.

What does the composer Donizetti mean for you?

Donizetti has meant a lot for my artistic career. I have probably experienced the best moments of my adventure in opera with Donizetti’s music. He has helped me a great deal. In a sense, I am grateful to Donizetti for everything he wrote because he has given me the opportunity to express myself beautifully and positively.

His music is uncharted territory for young conductors. You can’t just pick up a book that tells you how to conduct bel canto. If you want to conduct a bel canto work, you have to prepare the score in great detail, changing the dynamics here, adding an accent there and so on. It is like preparing a delicious meal. You might think you can buy the perfect chicken, stick it in the oven and you’re done, but that is not how it works. You have to prepare everything properly. You have to remove the unwanted parts and stuff it in the right way. You add rosemary and other herbs, you prepare the sauce, you carve the chicken correctly... Otherwise it will just be disappointing.

If you buy the score for Roberto Devereux and give it to a student conductor, they will feel helpless because the score doesn’t come with guidelines. If you conduct Stravinsky’s Firebird, Tchaikovsky’s sixth symphony – the Pathétique – or Verdi’s Falstaff, you will find all the instructions written down for you. I remember well how confusing I found the bel canto operas when I started to conduct them: why did I have to change this, why did have to do that? Working with the singers let me learn what I was supposed to do as a conductor. They gave me suggestions: “Do that here, it works better. And you’d be better off approaching it this way here. A rallentando would be useful here in helping me get my breath back.” So I had to learn all the rules myself by working with the singers.

Can you describe bel canto as a concept for us?

It is difficult to give a single unambiguous definition of bel canto. The term gets used in different contexts. We can give an aesthetic definition, we can define it as an approach to composition or writing music, or we can use it to refer to a period in opera. So there are a range of meanings and it all depends on what you want to describe.

As a conductor, I spent many years studying composition and I see bel canto more as a means of composition, which of course also becomes an emotional vehicle. If I had to summarise it in just a few words, I would say it is a way of writing music that reduces the orchestra to a very minimalist accompaniment, with a lot of repetition — minimalist in the modern sense too. Superimposed on this stripped-down accompaniment is an exquisite melodic line produced by the singers, who dominate the orchestra. The orchestra can have quite a hypnotic effect thanks to that minimalist approach. But the minimalism and neutrality of the orchestra also give the singers the opportunity to shine with their high notes, or show off their skills in going deep, or with rapid ornamentation and so on. That is classic bel canto. But there are times when I open the score of an opera from the late-nineteenth-century Italian repertoire, such as Madama Butterfly, and see phrases that make me think: that’s bel canto. You can even come across fantastic bel canto moments in Wagner’s Holländer or Weber’s Der Freischütz. Bel canto certainly doesn’t end with Donizetti!

Dutch text: Luc Joosten

Translation: Clare Wilkinson

Biography

Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex

Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex

Robert Devereux was an English nobleman, a distant relative of Elizabeth I and a favourite of the Queen. His great-grandmother on his mother’s side was Mary Boleyn, the sister of Anne Boleyn, Elizabeth’s mother. He had a successful career as a soldier in the Low Countries, which brought him to the attention of the English Court. In 1585, Elizabeth gave the young nobleman additional privileges and he was put in charge of her bodyguard only two years later. His ascendancy at the Royal Court was not without tensions, in part because his moodiness and ambitions repeatedly brought him into conflict with the Queen. Apparently, he was once on the point of drawing his sword after she cuffed him on the ear during a particularly heated exchange.

Despite their differences, Elizabeth still entrusted him in the war against Spain with the command of the fleet that captured Cadiz in the summer of 1596. However, this impressive military success did not satisfy him. Instead, he tried to mobilize his supporters at the Court against Lord Cecil and his son and heir Robert, which brought him into conflict with the Queen once again. He did not attend the fortieth anniversary of Elizabeth’s coronation as a result.

The major clash escalating the tension between Devereux and Elizabeth involved Ireland. After the two had reached a reconciliation, Devereux managed to get himself appointed Lord Deputy of Ireland, sent at the head of a large army to pacify the rebellious country. Three months passed during which he failed to gain control of the situation. When he agreed a truce on 6 September with O’Neill, the Earl of Tyrone, the leader of the rebels in Ulster, without consulting the Queen, it was the final straw; this time, the break was permanent.

Essex returned to England on 28 September 1599, even though the Queen had expressly forbidden him to do so. She was therefore understandably astonished when he appeared in her sleeping quarters one morning in Nonsuch Palace, before she had donned her wig or was decently clothed. The Queen’s Council met three times to decide on a judgment regarding his insubordination in Ireland, and it seemed initially as if his actions would go unpunished. However, the Queen had him confined to his rooms, saying “An unruly horse must be abated of his provender”. The house arrest raised the stakes and Robert started to plot his revenge.

In early February 1601, a meeting of conspirators was held to prepare a plot against the Queen. On 8 February, Essex and a small group of supporters attempted to storm the city of London. He also wanted to eliminate his enemy Sir Robert Cecil. However, the coup failed as he did not get the support of the people of London. That same night, Essex was arrested, declared an outlaw for committing treason and condemned to death. On the morning of 25 February 1601, he was beheaded in the Tower of London with three strokes of the axe. His executioner had in fact been condemned to death himself as a sailor in 1596 off the coast of Cadiz but was granted mercy by the same Robert Devereux. Robert Devereux was the last person to be beheaded in the Tower of London.

Biography

Elizabeth I, in the twilight days of her reign

Elizabeth I

The period after the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588 brought new difficulties for Elizabeth. The conflicts with Spain and in Ireland dragged on, the tax burden was becoming heavier and England’s economy was hit by poor harvests and the costs of war. Prices were rising and living conditions suffered. The oppression of Catholics also intensified during this period. To maintain the illusion of peace and prosperity, the Queen increasingly relied on propaganda and spies inside the country. In her final years, mounting criticism was reflected in a decline in her subjects’ affection for her.

The political scene was also poisoned by the struggle for the most powerful positions in the kingdom. The Queen’s personal authority was waning, as became clear from the affair involving her trusted physician Dr Lopez in 1594. When he was wrongly accused of treason by the Earl of Essex in an act of personal vengeance, she was unable to prevent the doctor’s execution despite her anger at his arrest and despite seemingly not believing in the accusations levied against him.

And yet this period of economic and political instability also saw an unprecedented burst of literary production in England. Various preeminent figures in English literature reached artistic maturity in the 1590s, including Christopher Marlowe and William Shakespeare. The idea of an Elizabethan golden age largely rests on the achievements of the architects, playwrights, poets and musicians who flourished during Elizabeth’s reign. But they did not have the Queen to thank for this as Elizabeth I was never a great patron of the arts.

Elizabeth I

“Eyes of youth have sharp sight but commonly not so deep as those of elder age.”

As Elizabeth grew older, her image changed. Portraits of her became less realistic and took on the character of mysterious icons that made her look much younger than she was in real life. A bout of smallpox in 1562 had left her scarred and partly bald, since when she had been dependent on wigs and cosmetics. Thanks to her love of sweet delicacies and fear of dentists, she experienced severe tooth decay and lost so many teeth that foreign ambassadors had trouble understanding her. Sir Walter Raleigh called her “a lady whom Time has surprised”.

The more Elizabeth’s beauty faded, the more her courtiers sang her praises. Elizabeth was happy to play this role, but she may genuinely have started to believe in the fantasy in her final decade. She was mad about the young, charming but moody Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, and forgave him the liberties he took. She repeatedly appointed him to key military positions, despite his irresponsible behaviour. When Devereux was beheaded after he was discovered to have conspired against Elizabeth, she realised that this fateful turn of events was partly due to her own misjudgement. An observer wrote in 1602: “Her delight is to sit in the dark, and sometimes with shedding tears to bewail Essex.”