Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny

Performance information

Voorstellingsinformatie

Performance information

Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny

Kurt Weill (1900-1950)

Duration

2 hours en 45 minutes, including one interval

The performance is sung in German, with Dutch and English subtitles.

Opera in three acts

Makers

Libretto

Bertolt Brecht

Musical direction

Markus Stenz

Stage direction

Ivo van Hove

Set and lighting design

Jan Versweyveld

Costume design

An D’Huys

Video

Tal Yarden

Dramaturgy

Koen Tachelet

Cast

Leokadja Begbick

Evelyn Herlitzius

Fatty

Alan Oke

Dreieinigkeitsmoses

Thomas Johannes Mayer

Jenny Hill

Lauren Michelle

Jim Mahoney

Nikolai Schukoff

Jack O’Brien/Tobby Higgins

Iain Milne

Bill

Martin Mkhize

Joe

Mark Kurmanbayev*

Sechs Mädchen von Mahagonny

Viola Cheung

Thembinkosi Magagula

Elisa Soster

Raphaële Green

Kadi Jürgens

Jessica Stakenburg

* Dutch National Opera Studio

Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra

Chorus of Dutch National Opera

Chorus master

Ad Broeksteeg

Co-production with

Festival d’Aix-en-Provence, Metropolitan Opera, Opera Ballet Vlaanderen, Grand Théâtre de Luxembourg

Production team

Instudering regie

Frans Willem de Haas

Assistant conductor

Aldert Vermeulen

Assistant chorus master

Irina Sisoyeva

Assistant director

Maarten van Grootel

Assistant set design

Bart van Merode

Assistant costume design

Fauve Ryckebusch

Assistent lighting design

Martijn Smolders

Assistent video design

Christopher Ash

Rehearsal pianists

Ernst Munneke

Irina Sisoyeva

Language coach

Stephan Rehm

Language coaches chorus

Cora Schmeiser

Inga Schneider

Orchestra inspector

Pauline Bruijn

Stage managers

Joost Schoenmakers

Roland Lammers van Toorenburg

Sanne van Loenen

Master carpenter

Jop van den Berg

Lighting manager

Coen van der Hoeven

Props manager

Remko Holleboom

Sound technician

David te Marvelde

Special effects

Koen Flierman

Peter Visser

Camera

Boris de Ruijter

Coach camera operator

Laurent Fontaine Czaczkes

First make-up artist

Trea van Drunen

Costume supervisor

Lars Willhausen

First dresser

Jenny Henger

Artistic planning

Sonja Heyl

Surtitle director

Eveline Karssen

Surtitle operator

Maxim Paulissen

Production management

Joshua de Kuyper

Set supervisor

Puck Rudolph

Chorus of Dutch National Opera

Tenors

Thomas de Bruijn

Pim van Drunen

Frank Engel

Livio Gabrielli

Erik Janse

Robert Kops

Leon van Liere

Tigran Matinyan

Martin van Os

Richard Prada|

Mitch Raemaekers

Raymond Sepe

Mirco Schmidt

Julien Traniello

Rudi de Vries

Basses

Peter Arink

Bora Balci

Nicolas Clemens

Emmanuel Franco

Jeroen van Glabbeek

Hans Pieter Herman

Arman Isleker

Tom Jansen

Dominic Kraemer

Matthijs Mesdag

Christiaan Peters

Hans Pootjes

Matthijs Schelvis

Jaap Sletterink

Marijn Zwitserlood

Extras

Keerthi Basavarajaiah

Loris Casalino

Andrea Child

Earl Daniël

Liah Frank

Niels Gordijn

Rowan Kievits

Mario Krastev

Federica Panariello

Renzo Popolizio (assistant camera)

Rowin Prins

Britt Scheltens

Alexey Shkolnik

Alicia Verdú

Mike Wijdenbosch

Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra

First violin

Vadim Tsibulevsky

Saskia Viersen

Tessa Badenhoop

Hike Graafland

Marieke Kosters

Marina Malkin

Paul Reijn

Henrik Svahnström

Second violin

David Peralta Alegre

Marlene Dijkstra

Mintje van Lier

Charlotte Basalo Vázquez

Wiesje Nuiver

Lilit Poghosyan Grigoryants

Joanna Trzcionkowska

Eva de Vries

Viola

Roeland Jagers

Laura van der Stoep

Odile Torenbeek

Marjolein de Waart

Suzanne Dijkstra

Michiel Holtrop

Avi Malkin

Merel van Schie

Anna Smith

Stephanie Steiner

Cello

Douw Fonda

Ilia Laporev

Atie Aarts

Nitzan Laster

Rik Otto

Anjali Tanna

Sebastian Koloski

Harry Broom

Double bass

Frank Dolman

Gabriel Abad Varela

Mario Torres Valdivieso

Julien Beijer

Sorin Orcinschi

Peter Rikkers

Flute

Hanspeter Spannring

Ellen Vergunst

Oboe

Toon Durville

Clarinet

Rick Huls

Saxophone

Deborah Witteveen

Marlon Valk

Jenita Veurink

Bassoon

Remko Edelaar

Contrabassoon

Jaap de Vries

Horn

Miek Laforce

Stef Jongbloed

Trumpet

Ad Welleman

Jeroen Botma

Marc Speetjens

Trombone

Harrie de Lange

Wim Hendriks

Tuba

David Kutz

Timpani

Theun van Nieuwburg

Percussion

Matthijs van Driel

Diego Jaen Garcia

Nando Russo

Piano

Daan Kortekaas

Ernst Munneke (bühne)

Banjo and guitar

Jeroen Kimman

Accordeon

Bart Lelivelt (bühne)

Zither

Dario Rossetti Bonell (bühne)

Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny in a nutshell

in het kort

In het kort

A merciless opera

Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny is all about the power of money and the ruthless way in which the people with money rule, dominate and manipulate the world. The city of Mahagonny is a capitalist ‘paradise’ where profit takes precedence over morality. Everything about Mahagonny is raw and callous, and that is how it is presented to audiences in composer Kurt Weill and librettist Bertolt Brecht’s uncompromising work. Their approach was not universally appreciated: the premiere in Leipzig in 1930 was disrupted by frequent booing and disturbances on the part of both the appalled bourgeoisie and the Nazis.

Brecht and epic theatre

Driven by his Marxist engagement, the dramatist, director and thinker Bertolt Brecht (1898-1956) advocated ‘epic theatre’ as the antithesis of classical theatre (as defined by Aristotle). In epic theatre, rather than developing empathy for the characters, audiences were supposed to feel distanced from the performance, allowing space for critical reflection. Alienating techniques, for instance the use of songs or directly addressing the audience, played a key role in creating this distance.

Brecht and Mahagonny

Bertolt Brecht saw opera as the product of a society obsessed with pleasure, a ‘culinary’ art form focused exclusively on entertainment. With Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny, Brecht and Weill launched a head-on attack, albeit taking the paradoxical approach of targeting the ‘culinary’ with an opera that makes use of the self-same ‘culinary’ techniques. It is as if the audience is being lured into a trap: even as they enjoy the entertainment, they are confronted with the disastrous consequences of their own pleasure culture.

Weill and Mahagonny

The composer Kurt Weill (1900-1950) shared Brecht’s views to some extent, although he was always more interested in renewing opera as a genre than in destroying it. Weill believed opera should aim for broader relevance to society and seek to appeal to the general public. To achieve this, opera needed to incorporate contemporary sounds such as jazz and popular dance music — the foxtrot, the shimmy and the tango.

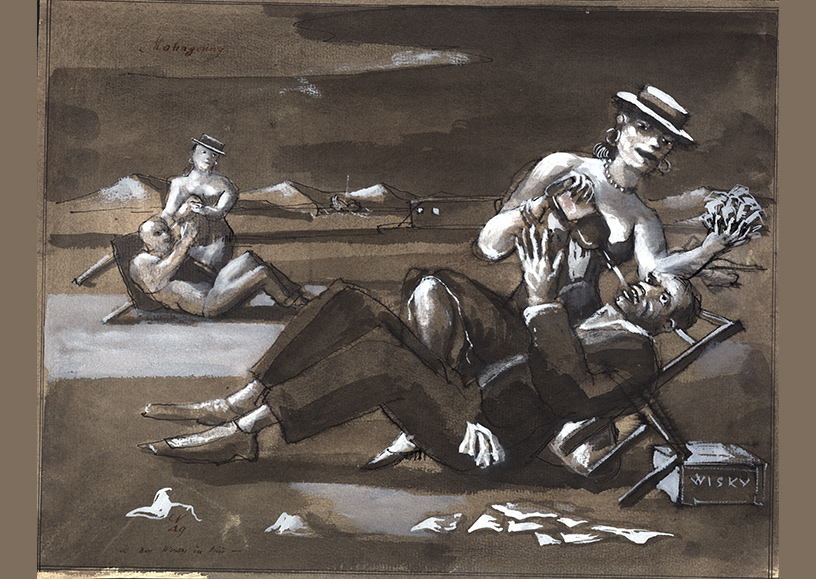

Ivo van Hove directs Mahagonny

In his stage direction, the director Ivo van Hove emphasises the artificiality of the city as a place that trades in illusions. This artificiality is reinforced by the frequent use of video images and green screens — modern-day alienating techniques.

Markus Stenz conducts Mahagonny

The conductor Markus Stenz, a specialist in the repertoire of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, is taking on Mahagonny. According to Stenz, Weill’s musical notation is rather ‘thin’, leaving plenty of scope for interpretative choices by the conductor.

The story

Follow te link below to read the story of Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny.

The story

The three criminals Leokadja Begbick, Fatty and Dreieinigkeitsmoses are on the run from the police. They end up in the desert, where they found the city of Mahagonny. Jenny and six other sex workers arrive in search of whisky, money and new customers. Jim, Jack, Bill and Joe, four lumberjacks from Alaska, also come to Mahagonny, loaded with cash and intent on having a good time. But they soon become bored. Jim is irritated by all the rules that have been introduced in Mahagonny to keep order. When a hurricane threatens to destroy Mahagonny, Jim calls on everyone to reject the rules.

Mahagonny escapes the hurricane and becomes a city where ‘anything goes’ – a place where people eat, drink, fight and fornicate. Jack gorges himself to an early death, Joe dies in a brawl with Dreieinigkeitsmoses and Jim loses all his money in a bet. Despite this, he invites everyone to have a drink with him. When it turns out he can’t pay the bill, he is arrested. Not having enough money is a capital offence in Mahagonny.

Jim is condemned to death in a show trial. After he has taken leave of Jenny, he is led to the gallows. He realises now that the happiness in Mahagonny was only ever an illusion. After Jim’s death, inflation hits Mahagonny and the city’s streets are filled with groups protesting for and against anything and everything. In the general chaos, the city burns to the ground.

Timeline Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill

Tijdlijn Bertolt Brecht en Kurt Weill

Timeline Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill

1898

Bertolt Brecht is born in Augsburg, Germany, to a middle-class family. At school, he meets Caspar Neher, who later becomes his regular set designer for his theatrical productions.

1900

Kurt Weill is born in Dessau, Germany. He grows up in the Jewish district, where his father leads the prayer singing in the synagogue.

1917

To avoid national service, Brecht enrols as a medical student in Munich. However, he devotes most of his time to the study of theatre and literature. In 1918, just before the end of the war, he is called up anyway and put to work as a nurse in a military hospital.

1918

Weill starts at the Hochschule für Musik in Berlin, where he is taught by the composer Engelbert Humperdinck. In 1919, he abandons his studies to support his family financially. He works as a répétiteur (in Dessau) and Kapellmeister (in Lüdenscheid). In 1920, Weill resumes his studies at the Preussische Akademie der Künste in Berlin, studying with Ferruccio Busoni.

1922

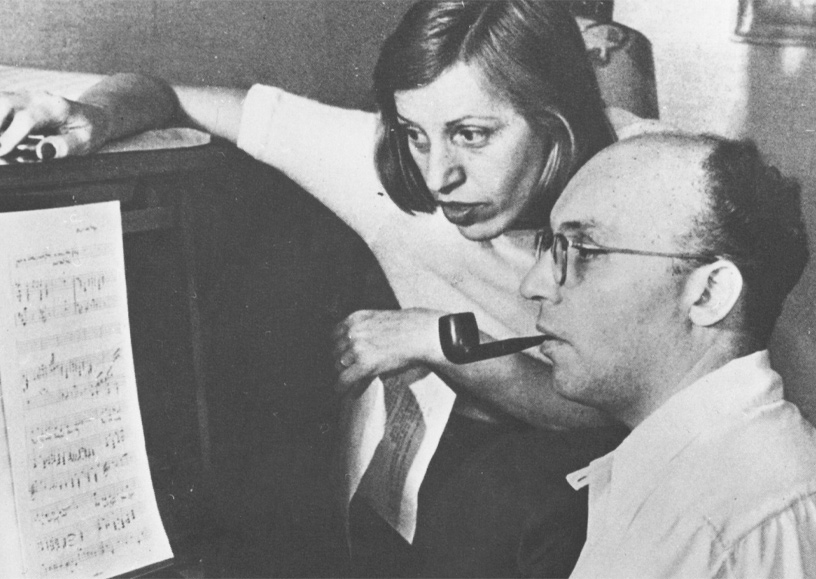

Weill becomes a member of the Novembergruppe, a left-wing artistic society in Berlin. Through this group, he meets the dramatist Georg Kaiser, with whom he would go on to create several operas. Kaiser introduces him to the singer and actress Lotte Lenya, whom he eventually married twice (once in 1926, and again in 1937 after they divorced in 1933).

1922

Weill becomes a member of the Novembergruppe, a left-wing artistic society in Berlin. Through this group, he meets the dramatist Georg Kaiser, with whom he would go on to create several operas. Kaiser introduces him to the singer and actress Lotte Lenya, whom he eventually married twice (once in 1926, and again in 1937 after they divorced in 1933).

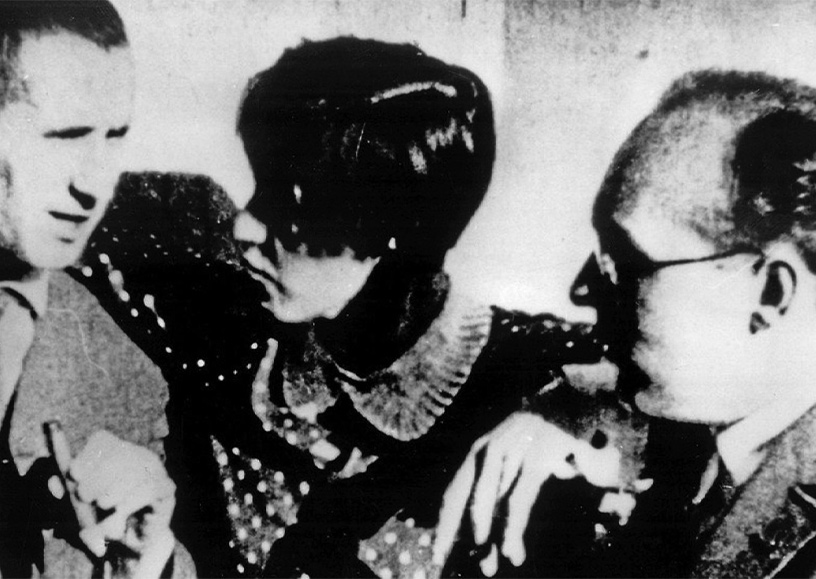

1927

Brecht and Weill meet for the first time. The composer needs a libretto for a short opera he has been commissioned to create for the Festival Deutsche Kammermusik Baden-Baden. The Mahagonny-Songspiel premieres on 17 July 1927. It would form the basis for a full-blown opera: Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny.

1928

On 31 August, Brecht and Weill’s Die Dreigroschenoper premieres in the Theater am Schiffbauerdamm in Berlin. Also known in English as the Threepenny Opera, it is based on John Gay’s satirical The Beggar’s Opera (1728). Elisabeth Hauptmann, Brecht’s creative close collaborator, translated the work into German and Brecht’s libretto is an adaptation of this version. Weill composed the music, which betrays strong influences of jazz, music hall and popular dance music.

1930

Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny premieres on 9 March in the Neues Theater in Leipzig. Nazis try in vain to have the production banned and then stage booing and brawls during the opening night performance. Many theatres that were planning to put on the opera after the premiere decide not to include it in their programmes after all.

1933

Weill’s Der Silbersee (with a libretto by Georg Kaiser) premieres on 18 February, two weeks after Adolf Hitler seizes power. Protests against Weill’s opera eventually lead to performances of it being banned. On 28 February, the day after the Reichstag Fire, Brecht leaves Germany. Weill follows suit on 21 March. On 7 June 1933, Die sieben Todsünden has its world premiere in the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées in Paris. It would be Brecht and Weill’s last major collaboration.

1935

Kurt Weill and Lotte Lenya settle in New York, where Weill makes a career composing works for Broadway, including Knickerbocker Holiday (1938), Lady in the Dark (1941) and One Touch of Venus (1943).

1941

Brecht too moves to the United States. In exile, he writes such major works as Mutter Courage und ihre Kinder, Der gute Mensch von Sezuan, Der aufhaltsame Aufstieg des Arturo Ui and Der kaukasische Kreidekreis.

1947

Brecht runs into trouble in the States due to his alleged Communist leanings. He is interrogated by the House Un-American Activities Committee. He decides to return to Europe.

1949

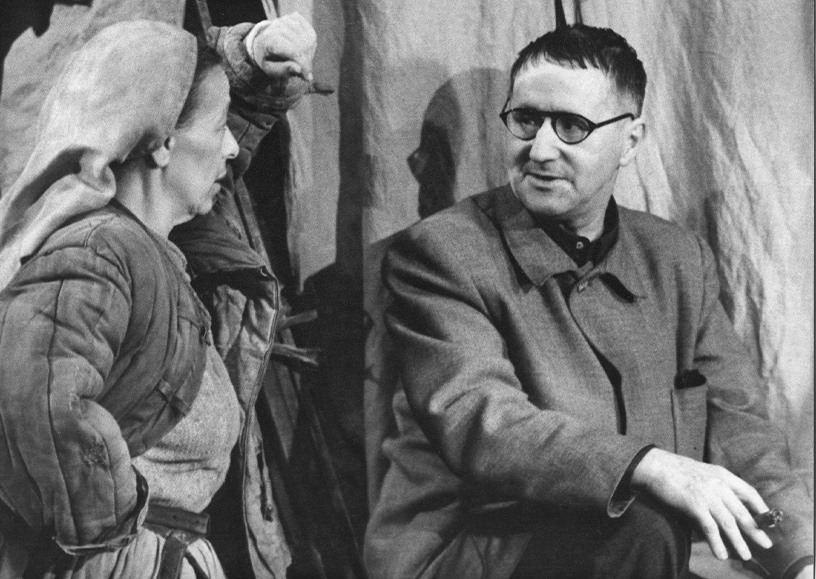

After a period in Switzerland, Brecht moves to East Berlin, where he starts his own theatre company, the Berliner Ensemble. He does not write many new works in his final years, preferring to concentrate on directing plays and nurturing a new generation of stage directors.

1950

Weill dies on 3 April from a heart attack. After his death, his widow Lotte Lenya takes charge of his artistic legacy. In the mid-1950s, she returns to Germany where she makes important recordings of Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny, Die Dreigroschenoper, Die sieben Todsünden and various of Weill’s songs.

1956

Brecht dies in Berlin on 14 August from a heart attack. After his death, Brecht’s wife Helene Weigel takes over leadership of the Berliner Ensemble until her own death in 1971.

‘Mahagonny is a fata morgana’

Interview with director Ivo van Hove on Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny.

‘Mahagonny is a fata morgana’

Ivo van Hove says he had dreamed for years of directing Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny. His production of the work premiered in Aix-en-Provence in 2019 and was originally due to come to Amsterdam in 2020, but the COVID pandemic made that impossible. Some three years later, Dutch National Opera audiences are finally able to experience Van Hove’s exceptional staging in an interpretation that reflects uncompromisingly on the beauty and cruelty of the world.

Van Hove unfolds a piece of paper on which some notes have been jotted down in neat handwriting in preparation for the interview. Right at the top is a quote from the American author and journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates, who was a source of inspiration for Van Hove in his direction of Brecht and Weill’s Mahagonny.

“I find Coates hugely fascinating as a writer. He is a kind of voyager in his home city of New York, and he mixes sociology and philosophy in highly personal reflections. He doesn’t think art has a duty to be hopeful or optimistic, or to make people feel better about the world. On the contrary, art should reflect the world in all its cruelty and beauty. That is what I try to do with my productions, and I believe that is also what Brecht and Weill are doing. Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny essentially tells the story of people who are unhappy with their current circumstances and are in search of something better, an Earthly paradise. They are a bunch of outcasts who have failed to make it in life, or at any rate have ended up on the margins of society. They are roaming around in an abortive search for gold and they’ve become stranded in a desert with nothing there. That’s where they decide to plant their flag and build a new world.”

As Brecht said: “The dissatisfied from all continents converge on the golden city of Mahagonny.”

“Exactly. They form a group and that gives them power. You could call it a movement, to use a modern word, even if they don’t achieve the result they were aiming for. They soon become caught in a huge misunderstanding, where they confuse prosperity — riches, money and possessions — with well-being, with feeling good and truly happy. They fail to attain the happiness they were hoping for, and eventually look for a scapegoat on whom to blame this failure. The opera ends with the murder of one of them, Jimmy, in the third act. That scene is crucial in my production. The entire community turns against one man, who is sacrificed to vent a collective frustration with everything that has gone wrong and what they have been unable to achieve in their pursuit of wealth. But of course that doesn’t solve the problem.”

A depressing ending?

“Mahagonny does indeed tell a sombre story of the condition of a particular community, what people are capable of and how easily it can all go wrong.”

Is this view of society as presented in Mahagonny also your own view?

“The works I create are very personal, but I don’t think my personal political beliefs should be evident in my productions. For example, I directed The Fountainhead by Ayn Rand, an exploration of extreme liberalism. Like Coates, I show the world as it is and I assume people are smart enough to reach their own conclusions. In the case of Mahagonny, I give an unrestrained portrayal of its awfulness, but I also reveal the finer aspects and the potential for a more positive outcome. There are poetic moments, with love blossoming between Jimmy and Jenny. So there are opportunities and there is the possibility of well-being, but in the end it proves unviable because the urge to increase wealth takes precedence over everything else.”

Weill believed opera should be about the pressing contemporary issues: ‘war, capitalism, inflation and revolution’. That quote seems tailor-made for our own times.

(laughs) “Yes, definitely the bit about inflation... In my stage direction, I chose not to simply transpose Mahagonny into a modern-day context, but there are plenty of links with our times. Take the storming of the Capitol in the US, where we saw an attack on democracy taking place before our eyes. It showed what the herd mentality can lead to and how we are once again living in a world where violence is seen as a legitimate means of enforcing your will. That barbaric element, which is so dominant in the third act of Mahagonny, has only become stronger in recent years. That is very worrying and it shows how incredibly relevant Mahagonny is today. Just before Mahagonny had its premiere in Aix-en-Provence in 2019, the gilets jaunes protesters turned out en masse in the streets. I saw graffiti in Paris that said, ‘Vivre, oui! Survivre, non!’ (Living? Yes! Just staying alive? No!) That is also the essential issue for the people of Mahagonny. They are not opportunists; they are driven by necessity. They include lumberjacks from Alaska who have worked hard, saved a little money and now want a better life.”

One emotional moment is when Mahagonny’s inhabitants wait anxiously as a hurricane approaches the city. We see feelings of worthlessness and vulnerability, but also of solidarity.

“That is indeed when solidarity reaches its peak among the group because they are genuinely threatened by this destructive force of nature. Theatrically, Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny is incredibly cleverly put together. The metaphors are spot-on. Brecht and Weill also used very advanced techniques to get their story across. Each scene starts with a spoiler, announcing what is about to happen. In Mahagonny this approach works well because it makes you pay more attention. It creates tension as you know things are going to go wrong and you start pondering why. In my stage direction, I emphasise that division into separate scenes by projecting and magnifying the spoilers. By doing that, I am respecting Brecht’s dramatic ideas. At the same time, the acting is very driven, very emotional and physical in my production.”

So we are invited to become emotionally involved with the characters. Isn’t that going against the spirit of Brecht’s approach?

“I once had a dramaturgy teacher called Alex Van Royen who may have been the best teacher I ever had. He became known for his interpretation of Georges in Hugo Claus’s play Vrijdag. He died many years ago. Van Royen had seen productions directed by Brecht himself, and he said the idea that his actors did not play their roles with empathy was a major misconception. On the contrary, he said, Brecht’s actors were some of the most Stanislavski-oriented actors in the world [referring to the method of acting where the actors immerse themselves in their roles and draw on their own emotional memories, ed.]. They acted with complete conviction and emotional intensity and that is also what I went for in my direction.”

A striking feature of your production is the use of cameras and green screens. The actors are filmed live and their silhouettes incorporated into projected film footage in real time.

“We start the opera with an empty stage. That is where the first scene is played, after which Mahagonny is built up. But Mahagonny is an illusion. Green screens are used in a lot of films these days: you think the actors are surrounded by the most amazing sets but in fact they are acting in front of these green screens and their scenes are subsequently projected on top of computer-generated images. It is an illusionary, intangible world that only exists in your imagination. The same applies to Mahagonny.

The use of green screens reaches a peak in the second act. Mahagonny has been built and the characters overindulge in everything they think will bring them happiness. They binge on food, box one another to death and gorge on empty, purely mechanical sex: stick it in, take it out, an emotionless dollop of a climax. Theirs is an empty and entirely artificial world. That is made painfully clear to them when they want to take the boat and leave Mahagonny but then discover they are in a film studio where nothing is real. In the third act, Jimmy is condemned to death in a show trial — another very topical element. The legal process is fake, a show, where you are even charged an admission fee. Someone takes on the role of God and can then pass judgment as if he were God. These are all choices that underline the utter artificiality. We eventually end up with an empty stage again. Nothing has changed. Mahagonny was a fata morgana, an illusion.”

Then there is Kurt Weill’s music. What is so good about that?

“I find the music wonderful, better even than the Dreigroschenoper, which is another powerful work. In general, I’m not a great fan of Brecht’s plays because they are often too ‘didactic’, his Lehrstücke being a good example. But I do like his ideas about what the performing arts should be, and his philosophy reaches fruition in his works of musical theatre, especially when combined with the music of Kurt Weill. With this music, catchy stuff that stays in your head, Weill manages to make Brecht’s ideas accessible and adds an enduring urgency. He lets certain musical themes recur very effectively like a kind of perpetuum mobile, an unstoppable wave — which engulfs Jim too at the end. By the way, it is fascinating to note that the word ‘opera’ was crucial for Weill and Brecht in Mahagonny. They most definitely did not want it to be called musical theatre and you’re not allowed to put on the work without casting opera singers — that is a contractual stipulation. Their idea was that to portray life, you had to magnify it.”

Text: Ilse Degryse and Piet De Volder for Opera Ballet Vlaanderen (2022)

Translation: Clare Wilkinson

‘Weill offers a lot of scope for interpretation’

Interview with the conductor Markus Stenz.

‘Weill offers a lot of scope for interpretation’

Markus Stenz, who is known for his great affinity with the twentieth-century and contemporary repertoire, first conducted Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny thirty years ago. Now he is returning to the work, bringing a greater maturity.

Markus Stenz believes the themes addressed in the opera are as relevant as ever today, almost one hundred years after it was first performed. “Mahagonny is an enduring work because it combines everything that can be expressed through art. I find the opera incredibly pertinent for our time. Indeed, I believe every staging of this masterpiece should aim to elucidate the link between the context then and now. I certainly expect this production by the director Ivo van Hove to strike the right chord. He is better than anyone at tailoring his productions to the present day.”

Maturity

Stenz first conducted Mahagonny in the early 1990s, when he was the chief conductor of the London Sinfonietta, in a production directed by Ruth Berghaus for Staatsoper Stuttgart. “The Berlin Wall had fallen just three years earlier and the wounds of a divided Germany were still smarting. Berghaus came from the DDR, which meant she was acutely aware of the connotations of Brecht’s razor-sharp and sometimes acerbic libretto. I have to confess that it was rather different for me at the time: I was in the early days of my career and less mature.”

“Weill’s abrasive music has many layers, which can take on a finely honed meaning and painful beauty in the right hands. It will be quite fascinating, inspiring and challenging for me to see how my creativity has developed in the past three decades. I will undoubtedly make different creative decisions now compared to the first time.”

“Like with most scores I deal with these days, I will focus explicitly on the musical notation. I find this aspect particularly interesting in Weill’s scores. That’s because his compositions are written quite ‘thinly’ — far more so than some other modern-day scores. Weill just gives us the outline of the music, but his score doesn’t tell you anything about the precise sonority, the principal parts, the harmonic changes or how to create momentum. That is very much up to the interpretation of the performers.”

Multiple versions

A complicating factor is that we don’t just have a single version of Weill’s Mahagonny. The composer wrote several versions, opening up an abundance of musical possibilities. Stenz acknowledges this is a challenge, but one he is eager to embrace: “Should you include the ‘Kraniche Duett’, for example, which was originally written to replace a censored brothel scene? How many musicians should you have on stage? And which version of the ‘Havana-Lied’ should you use? Weill wrote a second version of the song for his wife, Lotte Lenya, who sang the lead role in the Berlin production of 1931.”

“According to Kim Kowalke, the president of the Kurt Weill Foundation, Weill’s hand-written score contains the numbers 6-3-2-2 next to the string parts, but no one knows whether these numbers refer to the number of musicians or something completely different. So whenever you perform Mahagonny, you can’t avoid taking all kinds of decisions that inevitably affect the musical development and dramatic arc.”

Opera or music theatre

Like Leonard Bernstein’s Candide, a work that crosses the boundaries of music theatre and opera, Mahagonny is sometimes classed as music theatre. But Brecht and Weill themselves were explicit about creating an opera: they wanted to revolutionise both the genre itself and its audiences. Stenz also sees Mahagonny as an opera. “The Berlin production of 1931 was a scaled-down version for the Berlin Theater am Schiffbauerdamm, adapted to suit ‘singing actors’ like Lotte Lenya. But the original Mahagonny is a proper opera, and you couldn’t possibly stage it using only ‘singing actors’. As in other of Weill’s works, the acting is undeniably important, but these days opera singers are perfectly capable of that. They also have the advantage that they can be heard above the orchestra!”

Text: Naomi Teekens

Translation: Clare Wilkinson

Bertolt Brecht's notes on Mahagonny

Bertolt Brechts aantekeningen bij Mahagonny

Bertolt Brechts notes on Mahagonny

In his ‘Anmerkungen zur Oper Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny’ (1930), Bertolt Brecht considers how Mahagonny relates to traditional opera, which, according to Brecht, is primarily an intoxicating stimulant. According to Brecht, Mahagonny was deliberately set up as an opera: a work of art made for an enjoyment-oriented theatrical company. He goes on to state that the opera also has a provocative effect by making ‘pleasure’ its subject. Brecht devotes most of the text to the formal innovations of Mahagonny, which he connects to his theory of the ‘epic theatre’. In his text, Brecht gives a list of characteristics of ‘epic theater’ that has become famous as an ultra-short summary of his theatrical theory. The following is a translated fragment of his text.

Our existing opera is a culinary opera. It was a means of pleasure long before it turned into merchandise. It furthers pleasure even where it requires, or promotes, a certain degree of education, for the education in question is an education of taste. To every object it adopts a hedonistic approach. It ‘experiences’, and it ranks as an ‘experience’.

Why is Mahagonny an opera? Because its basic attitude is that of an opera; that is to say, culinary. Does Mahagonny adopt a hedonistic approach? It does. Is Mahagonny an experience? It is an experience. For… Mahagonny is a piece of fun.

The irrationality of the opera

The opera Mahagonny pays conscious tribute to the senselessness of the operatic form. The irrationality of opera lies in the fact that rational elements are employed, solid reality is aimed at, but at the same time it is all washed out by the music. A dying man is real. If at the same time he sings we are translated to the sphere of the irrational. (If the audience sang at the sight of him the case would be different.)

The more unreal and unclear the music can make the reality – though there is of course a third, highly complex and in itself quite real element which can have quite real effects but is utterly remote from the reality of which it treats – the more pleasurable the whole process becomes: the pleasure grows in proportion to the degree of unreality. The term ‘opera’ – far be it from us to profane it – leads, in Mahagonny’s case, to all the rest. […]

Pleasure as subject and form

As for the content of this opera, its content is pleasure. Fun, in other words, not only as form but as subject-matter. At least, enjoyment was meant to be the object of the inquiry even if the inquiry was intended to be an object of enjoyment. Enjoyment here appears in its current historical role: as merchandise.

Opera and provocation

It is undeniable that at present this content must have a provocative effect. In the thirteenth section, for example, where the glutton stuffs himself to death; because hunger is the rule. We never even hinted that others were going hungry while he stuffed, but the effect was provocative all the same. It is not everyone who is in a position to stuff himself full that dies of it, yet many are dying of hunger because this man stuffs himself to death. His pleasure provokes, because it implies so much. In contexts like these the use of opera as a means of pleasure must have provocative effects today. Though not of course on the handful of operagoers. Its power to provoke introduces reality once more. Mahagonny may not taste particularly agreeable; it may even (thanks to guilty conscience) make a point of not doing so. But it is culinary through and through. Mahagonny is nothing more or less than an opera.

Innovations

Opera had to be brought up to the technical level of the modern theatre. The modern theatre is the epic theatre. The following table shows certain changes of emphasis as between the dramatic and the epic theatre:

| Dramatic theatre | Epische vorm van het theater |

| Plot | Narrative |

| Implicates the spectator in a stage situation | Turns the spectator into an observer, but |

| Wears down his capacity for action | Arouses his capacity for action |

| Provides him with sensations | Forces him to take decisions |

| Experience | Picture of the world |

| The spectator is involved in something | He is made to face something |

| Suggestion | Argument |

| Instinctive feelings are preserved | Brought to the ponit of recognition |

| The spectator is in the thick of it, shares the experience | The spectator stands outside, studies |

| The human being is taken for granted | The human being is the object of the inquiry |

| He is unalterable | He is alterable and able to alter |

| Eyes on the finish | Eyes on the course |

| One scene makes another | Each scene for itself |

| Growth | Montage |

| Linear development | In curves |

| Evolutionary determinism | Jumps |

| Man as a fixed point | Man as a process |

| Thought determines being | Social being determines thought |

When the epic theatre’s methods begin to penetrate the opera the first result is a radical separation of the elements. The great struggle for supremacy between words, music and production – which always brings up the question ‘which is the pretext for what?’: is the music the pretext for the events on the stage, or are these the pretext for the music? etc. – can simply be bypassed by radically separating the elements.

Separation of words, music and setting

So long as the expression ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’ (or ‘integrated work of art’) means that the integration is a muddle, so long as the arts are supposed to be ‘fused’ together, the various elements will all be equally degraded, and each will act as a mere ‘feed’ to the rest. The process of fusion extends to the spectator, who gets thrown into the melting pot too and becomes a passive (suffering) part of the total work of art. Witchcraft of this sort must of course be fought against. Whatever is intended to produce hypnosis, is likely to induce sordid intoxication, or creates fog, has got to be given up. Words, music and setting must become more independent of one another.

Music

For the music, the change of emphasis proved to be as follows:

| Dramatic opera | Epic opera |

| The music dishes up | The music communicates |

| Music which heightens the text | Music which sets forth the text |

| Music which proclaims the text | Music which takes the text for granted |

| Music which illustrates | Which takes up a position |

| Music which paints the psychological situation | Which gives the attitude |

Music plays the chief part in our thesis.

Text

We had to make something straightforward and instructive of our fun, if it was not to be irrational and nothing more. The form employed was that of the moral tableau. The tableau is performed by the characters in the play. The text had to be neither moralizing nor sentimental, but to put morals and sentimentality on view. Equally important was the spoken word and the written word (of the titles). Reading seems to encourage the audience to adopt the most natural attitude towards the work.

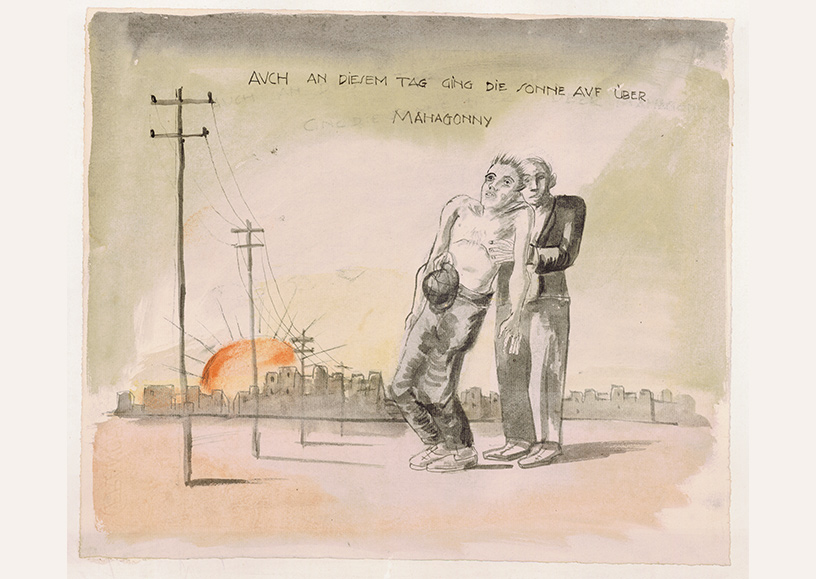

Setting

Showing independent works of art as part of a theatrical performance is a new departure. Neher’s projections [Neher was Brecht’s regular set designer – ed.] adopt an attitude towards the events on the stage; as when the real glutton sits in front of the glutton whom Neher has drawn. In the same way the stage unreels the events that are fixed on the screen. These projections of Neher’s are quite as much an independent component of the opera as are Weill’s music and the text. They provide its visual aids. Of course such innovations also demand a new attitude on the part of the audiences who frequent opera houses.

Text: Bertolt Brecht

Translation: Wim Nooteboom en Jacq Firmin Vogelaar

Kurt Weill on the gestic character of music

Kurt Weill over het gestieke karakter van de muziek

Kurt Weill on the gestic character of music

In his essay Über den gestischen Charakter der Musik (1929), composer Kurt Weill reflects on the kind of musical theatre he envisions. According to Weill, the situation and social relations of the theatrical context should be expressed in the music. He connects his thinking to the notion of Gestus – Bertolt Brecht’s term for the ways in which social relations are expressed in acting, through elements such as posture, intonation, and facial expression. The following is a translated fragment of his text.

In my attempts to arrive at a basic form for the musical theatre, I noticed several things which at first seemed to me to constitute entirely new insights but which after a closer look were revealed as but logical parts of the whole historical situation. While working on my own compositions, I constantly forced myself to answer the question: What occasions for music does the theatre offer? But as soon as I looked back at the operas written by myself and others, another question arose: What is the nature of music which is found in the theatre, and does such music have definite characteristics which label it music of the theatre?

After all it has often been stated that a number of important composers have either never paid any attention to the stage or that they have tried in vain to conquer the stage. There surely must be definite qualities which make a particular kind of music seem suitable for the theatre, and I believe they can be resumed under a single head, which I call music’s gestic character.

Unromantic theatre

In doing so I postulate a form of theatre which constitutes the only possible foundation for opera in our time. The theatre of the past epoch was written for sensual enjoyment. It aimed at titillating, exciting, inciting, and upsetting the spectator. It gave first place to the story, and to convey a story it had recourse to every theatrical accessory, from real grass to the treadmill stage. And whatever it granted the spectator, it could not deny its creator; he too felt sensual enjoyment when he wrote his work, for he experienced the “intoxication of the creative moment,” the ecstasy of the creative impulse of the artist, and other sensations of pleasure.

The other type of the theatre which is in the process of being established, presupposes a spectator who follows the action with the composure of a thinking man and who - since he wishes to think - considers demands made on his sensory apparatus an intrusion. This type of theatre aims to show what a man does. It is interested in material things only up to the point at which they furnish the frame of or the pretext for human relations. It places greater value upon the actors than upon the trappings of the stage. It denies its creator the sensuality its audience chooses to do without. This theatre is unromantic to the highest degree, for the “romantic” in art excludes the process of thinking: it works with narcotic devices, it shows man in an exceptional state and during its flowering (in the case of Wagner) it had no image of the human being.

If one applies the two ideas of the theatre to the opera, it appears that the composer of today may no longer approach his text from a position of sensual enjoyment. As far as the opera of the nineteenth and the beginning twentieth century is concerned, the task of music was to create atmosphere, to underscore situations, and to accentuate the dramatic. Even that type of musical theatre which used the text merely as an excuse for free and uninhibited composition is in the final analysis only the logical consequence of the romantic ideal of the opera, because in it the music participated even less in the carrying-out of the dramatic idea than in the music-drama.

Gestic music

The structure of an opera is faulty if a dominant place is not given to the music in its total structure and the execution of its smallest part. The music of an opera may not leave to the libretto and to the stage-setting the whole task of carrying the dramatic action and its idea; it must be actively involved in the presentation of the individual episode.

And since to represent human beings is the main task of the theatre of today the music too must be related solely to man. However, it is well known that music lacks all psychological or characterizing capabilities. On the other hand, music has one faculty which is of decisive importance for the presentation of man in the theatre: it can reproduce the gestus which illustrates the action on stage, it can even create a kind of basic gestus which forces the actor into a definite attitude which precludes every doubt and every misunderstanding concerning the relevant action. In an ideal situation it can fix this gestus so clearly that a wrong representation of the action concerned is impossible.

Every observant spectator knows how often even the most simple and the most natural human actions are represented on the stage by wrong sounds and by misleading movements. Music can set down the basic tone and the basic gestus of an action to the extent that a wrong interpretation can be avoided, while still affording the actor ample opportunities to display his individual style. Naturally gestic music is by no means limited to the setting of texts and if we accept Mozart’s music in every form, even his non-operatic music, as dramatic we do so because it never surrenders its gestic character.

Music is gestic wherever an action relating human beings to each other is represented in a naïve manner - most strikingly in the recitatives of Bach’s Passions, in the operas of Mozart, in Fidelio, and in the work of Offenbach and Bizet. In “This picture is bewitchingly beautiful” [“Dies Bildnis ist bezaubernd schön” – an aria from The Magic Flute – ed.] the attitude of a person who looks at a picture is completely fixed by the music. He can hold the picture in his right or left hand, he can hold it up or lower it, he can be set off by a spotlight or he might stand in the dark – his basic attitude will be right because the music will have dictated it.

Rhythmic determination of the text

What gestic means does music have at its disposal? First of all, there is the rhythmic fixing of the text. Music has the power of recording in written form the accents of speech, the distribution of short and long syllables, and most important – pauses. In this manner most sources for a wrong treatment of the libretto on the stage are eliminated. One can –to say this in passing –interpret a passage rhythmically in various ways, and even the same gestus can be expressed in various rhythms; the decisive point is, whether the gestus is correct. This setting of the rhythms on the basis of the text constitutes no more than the foundation of music that is gestic.

The really productive work of the composer begins when he uses all the other means of musica expression to make contact between the word itself and what it is trying to express. The melody likewise contains the gestus of the action which is to be presented but since the stage action is already rhythmically saturated, there exists far more elbow-room for formal, melodic and harmonic invention than in purely descriptive music or in music which merely runs parallel to the action and which is in constant danger of being drowned out.

The rhythmic restriction imposed by the text is therefore no greater a limitation than the formal scheme imposed by the Fugue, the Sonata, the Rondo is for the classical master. Within the framework of such rhythmically predetermined music all devices of melodic elaboration, of harmonic and rhythmic differentiation are possible, if only the overall musical tensions correspond to the gestic development. Thus, a coloratura-type lingering on one syllable is justified by a gestic lingering at the same point [in the story].

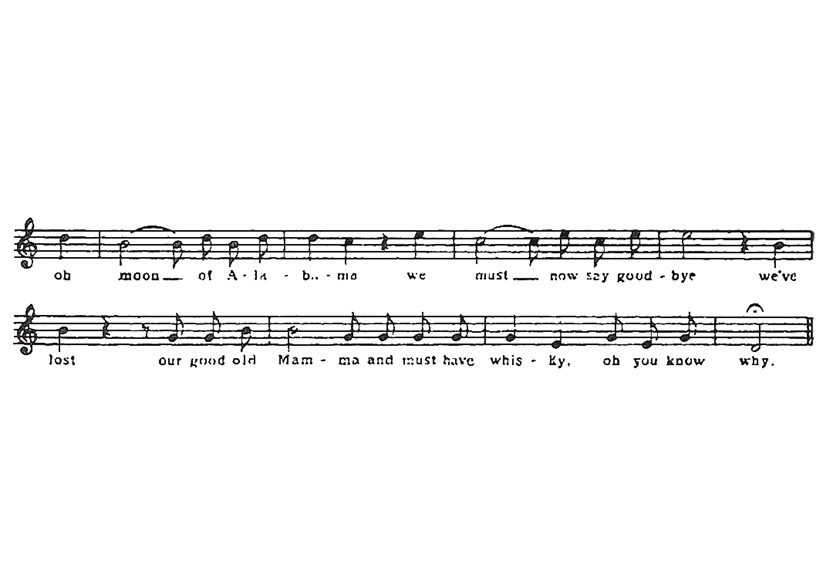

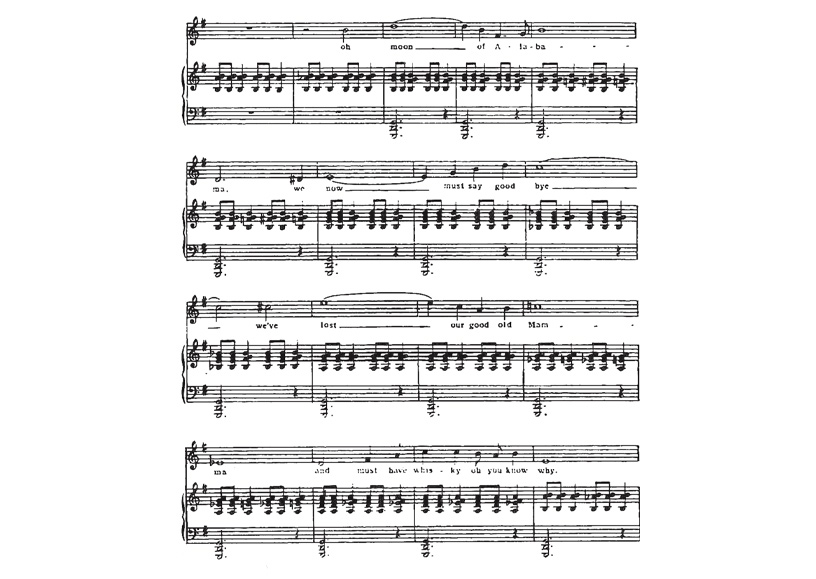

Alabama Song

I shall give an example taken from my own practice. Brecht formerly printed tunes to same of his poems because he felt the need to make the gestus clear. Here a basic gestus is being rhythmically defined in the simplest way, while the melody catches that wholly personal and inimitable way of singing which Brecht adopted when performing his songs. In this version the “Alabama Song” looks as follows:

One can see that this is merely a recording of the rhythm of speech and cannot be used as music. In my own setting of the same text the same basic gestus has been established, only it has – in my case – really been “composed” by means of the far ampler means of the composer. The song has – in my case – a much broader basis, extends much farther afield melodically speaking, and has a very different rhythmic foundation – but the gestic character has been preserved, although it appears in a totally different form:

One more thing needs to be said: that by no means all texts can be set in a gestic manner. The new form of the theatre which I assume for the purpose of my argument is used nowadays by very few poets, but it is only this form which permits and allows gestic language. The problem which I have touched upon in this essay is thus essentially a problem of modern drama.

But the type of theatre which aims at presenting human beings finds music indispensable because of its ability to clarify the action by gestic means. And only a type of drama which finds music indispensable can be completely adapted to the needs of that purely musical work of art which we know as “opera”.

Text: Kurt Weill

Translation: Erich Albrecht

programmaboek

Become a Friend of Dutch National Opera

Friends of Dutch National Opera support the singers and creators of our company. That friendship is indispensable to them, and we are happy to do something in return. For Opera Friends, we organise exclusive activities behind the scenes and online. You will receive our Friends magazine and have priority in ticket sales.