Il trittico

Performance information

Voorstellingsinformatie

Performance information

Il trittico

Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924)

Duration

3 hours and 45 minutes, including two intermissions

This performance is sung in Italian, with Dutch and English surtitles.

Musical direction

Lorenzo Viotti

Stage direction

Barrie Kosky

Set design

Rebecca Ringst

Costumes

Victoria Behr

Lighting design

Joachim Klein

Il tabarro

Libretto

Giuseppe Adami

Michele

Daniel Luis de Vicente

Luigi

Joshua Guerrero

Tinca

Mark Omvlee

Talpa

Sam Carl

Giorgetta

Leah Hawkins

Frugola

Raehann Bryce-Davis

Amante

Inna Demenkova

Amante / Un venditore di canzonette

Tigran Matinyan**

Suor Angelica

Libretto

Giovacchino Forzano

Suor Angelica

Elena Stikhina

La zia principessa

Raehann Bryce-Davis

La badessa

Helena Rasker

La suora zelatrice

Polly Leech

La maestra delle novizie

Eva Kroon

Suor Genovieffa

Inna Demenkova

Suor Osmina

Ruth Willemse**

Suor Dolcina / Prima conversa

Sophia Hunt*

La suora infermiera

Martina Myskohlid*

Prima cercatrice

Lisette Bolle**

Seconda cercatrice

Yvonne Kok**

Seconda conversa

Elsa Barthas**

La novizia

Vida Matičič Malnaršič**

Chorus soloists

Caroline Cartens**

Anna Emelianova**

Tomoko Makuuchi**

Elizabeth Poz**

Klarijn Verkaart**

Gianni Schicchi

Libretto

Giovacchino Forzano

Gianni Schicchi

Daniel Luis de Vicente

Lauretta

Inna Demenkova

Zita

Helena Rasker

Rinuccio

Joshua Guerrero

Gherardo

Mark Omvlee

Nella

Sophia Hunt*

Betto di Signa

Sam Carl

Simone

Scott Wilde

Marco

Georgiy Derbas-Richter*

La Ciesca

Polly Leech

Maestro Spinelloccio

Tomeu Bibiloni

Ser Amantio di Nicolao

Frederik Bergman

Pinellino

Emmanuel Franco**

Guccio

Christiaan Peters**

Gherardino

Dimitri Bos/Jeremy Blanvillain (Nieuw Vocaal Amsterdam)

* Dutch National Opera Studio

** Chorus of Dutch National Opera

Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra

Chorus of Dutch National Opera

Chorus master

Edward Ananian-Cooper

Nieuw Amsterdams Kinderkoor (part of Nieuw Vocaal Amsterdam)

Children’s chorus master

Anaïs de la Morandais

Production team

Assistant conductor

Boudewijn Jansen

Junior assistant conductor

Alejandro Cantalapiedra

Assistant directors

Astrid van den Akker

Noah van Renswoude

Assistant director during performances

Astrid van den Akker

Intern direction

Nadia Bakhshieva

Rehearsal pianists

Jan-Paul Grijpink

William Kelley

Language coach

Rita de Letteriis

Language coach chorus

Valentina di Taranto

Assistant chorus master

Kuo-Jen Mao

Stage management

Marie-José Litjens

Roland Lammers van Toorenburg

Jossie van Dongen

Artistic planning

Vere van Opstal

Orchestra representative

Pauline Bruijn

Assistant set design

Annett Hunger

Costume supervisor

Claire Nicolas

Master carpenter

Edwin Rijs

Lighting manager

Peter van der Sluis

Props master

Niko Groot

Special Effects

Ruud Sloos

Koen Flierman

Props team leader

Jolanda Borjeson

First dresser

Jenny Henger

First make-up artist

Trea van Drunen

Sound technician

David te Marvelde

Dramaturgy

Laura Roling

Surtitle director

Eveline Karssen

Surtitle operator

Irina Trajkovska

Head of the music library

Rudolf Weges

Set supervisor

Mark van Trigt

Production manager

Emiel Rietvelt

Chorus of Dutch National Opera

Sopranos

Lisette Bolle*

Jeanneke van Buul

Caroline Cartens

Anna Emelianova*

Nicole Fiselier

Melanie Greve

Oleksandra Lenyshyn

Simone van Lieshout

Tomoko Makuuchi*

Vida Matičič Malnaršič*

Vesna Miletic

Sara Pegoraro

Elizabeth Poz

Altos

Elsa Barthas*

Anneleen Bijnen

Rut Codina Palacio

Yvonne Kok*

Fang Fang Kong

Maria Kowan

Itzel Medecigo

Marieke Reuten

Carla Schaap

Klarijn Verkaart*

Ruth Willemse*

Tenors

Thomas de Bruijn

Milan Faas

Livio Gabbrielli

Raimonds Linājs

Roy Mahendratha

Sullivan Noulard

Mitch Raemaekers

Mirco Schmidt

Raymond Sepe

Julien Traniello

Rudi de Vries

Basses

Emmanuel Franco

Julian Hartman

Sander Heutinck

Tom Jansen

Matthijs Mesdag

Maksym Nazarenko

Gulian van Nierop

Christiaan Peters

Matthijs Schelvis

Vincent Spoeltman

René Steur

Rob Wanders

* Il tabarro: Midinettes

Nieuw Amsterdams Kinderkoor

Zeynep Ayar

Pheline Bennebroek

Jeremy Blanvillain

Dimitri Bos

Floren Brozius

Lidewij Burgerhout

Roek Burgerhout

Sophie Collé

Marin Foley

Catharina Halsema

Sophia Iriarte

Mara Jacobs

Audrey Johnson

Calla Kemper

Mia Kindt

Barbara Klee

Livia Kolk

Anaís Matias Khmelinskaia

Eliana Moreno Castaneda

Sanne Mostert

Nora van den Nieuwenhof

Lidewij Nieuwenhuizen

Lois Nollet

Thalia Oyewole

Jiya Patel

Cato Pleijsier

Looren Schenau

Kanak Vanam

Wanda Wiedijk

Children’s chorus master Suor Angelica:

Anaïs de la Morandais

Instudering Dmitri Bos / Jeremy Blanvillain (Gherardino in Gianni Schicchi)

Extras

Dick Addens

Renato Bertolino

Earl Daniël

Giacomo Della Marina

Creso Filho

Rowin Prins

Renzo Popolizio

Reindert van Rijn

Hans van Rijswijk

Yonatan Stakenburg

Valentin Quitman

Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra

First violin

Vadim Tsibulevsky

Saskia Viersen

Koen Stapert

Valentina Bernardone

Marieke Kosters

Robin Veldman

Mascha van Sloten

Karolina Walarowska

Anuschka Franken

Henrik Svahnström

Irene Nas

Hike Graafland

Paul Reijn

Jenneke Tesselaar

Second violin

David Peralta Alegre

Marlene Dijkstra

Mintje van Lier

Marieke Boot

Natália Salgado Ribeiro

Wiesje Nuiver

Anita Jongerman

Joanna Trzcionkowska

Karina Korevaar

Jeanine van Amsterdam

Eva de Vries

Lilit Poghosyan Grigoryants

Viola

Dagmar Korbar

Odile Torenbeek

Marjolein de Waart

Avi Malkin

Michiel Holtrop

Arwen Salama-van der Burg

Ursula Skaug

Suzanne Dijkstra

Stephanie Steiner

Anna Smith

Cello

Ilia Laporev

Douw Fonda

Carin Nelson

Atie Aarts

Anjali Tanna

Rik Otto

Nitzan Laster

Sebastian Koloski

Double bass

Luis Cabrera Martin

Gabriel Abad Varela

Mario Torres Valdivieso

Peter Rikkers

Sorin Orcinschi

Julien Beijer

Flute

Hanspeter Spannring

Andreia Serra da Costa

Piccolo

Elke Elsen

Oboe

Toon Durville

Maxime le Minter

Cor anglais

Juan Pedro Martinez

García-Casarrubios

Clarinet

Rick Huls

Tom Wolfs

Bass clarinet

Herman Draaisma

Bassoon

Remko Edelaar

Dymphna van Dooremaal

Horn

Fokke van Heel

Stef Jongbloed

Miek Laforce

Fred Molenaar

Trumpet

Ad Welleman

Jeroen Botma

Marc Speetjens

Trombone

Harrie de Lange

Wilco Kamminga

Dick Bolt

Cimbasso

David Kutz

Timpani

Theun van Nieuwburg

Percussion

Matthijs van Driel

Diego Jaen Garcia

Menno Bosgra

Gerda Tuinstra

Harp

Sandrine Chatron

Celesta

Justyna Maj

Banda Il tabarro

Anneke Romeijn (cornet)

Josefien de Waele (harp)

Banda Suor Angelica

Ellen Vergunst (piccolo)

Anneke Romeijn (trumpet)

Niek Jacobs (trumpet)

Abigail Rowland (trumpet)

Bence Csepeli (percussion)

Lennard Nijs (percussion)

Jan-Paul Grijpink (organ)

Celia Garcia Garcia (piano)

Kimball Huigens (piano)

Banda Gianni Schicchi

Diego Jaen Garcia (percussion)

In a nutshell

Il trittico in a nutshell: about Il tabarro, Suor Angelica and Gianni Schicchi.

In a nutshell

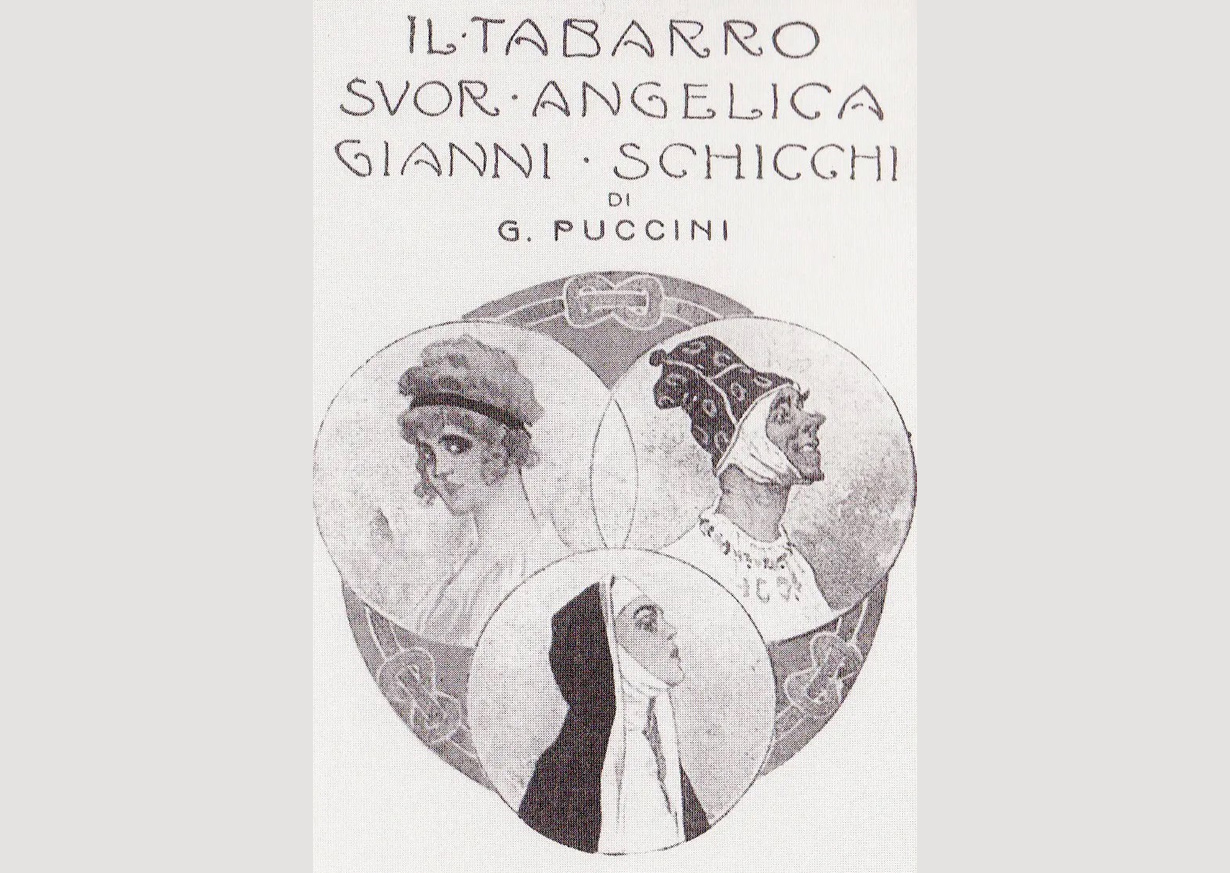

Drama in different colours

Giacomo Puccini first toyed with the idea of creating an operatic evening that would consist of three different one-act operas, each with its own distinctive atmosphere and colour, as early as 1900. Just as he had achieved maximum dramatic impact in his earlier opera La bohème (1896) by juxtaposing and combining moments of infectious joy and intense sorrow, he again intended to work from contrasts – albeit on a very different scale. He aimed to paint an overall picture of the human condition in three different colours, building a triptych out of a tragic work, a sentimental one and

a comic one.

Il tabarro

In May 1912, Puccini attended a performance of Didier Gold’s one-act drama La houppelande (the cloak) in Paris. The violent drama, set in an oppressive and hopeless contemporary social milieu, struck Puccini as an ideal source for his one-act opera with a ‘tragic’ colour. Italian librettist Giuseppe Adami turned the play into a compact operatic libretto according to Puccini’s meticulous instructions.

Suor Angelica

For a long time, Puccini failed to find suitable material for the other two operas of his Trittico. This changed when he came into contact with the young writer Giovacchino Forzano. Instead of relying on existing material, Forzano wrote two original libretti of his own: Suor Angelica and Gianni Schicchi. Inspired by the Stations of the Cross of Christ, Suor Angelica became a one-act opera in seven separate parts. From the opening, in which the sound of church bells is heard and picked up by the orchestra, Puccini masterfully depicts a monastic community cut off from the outside world.

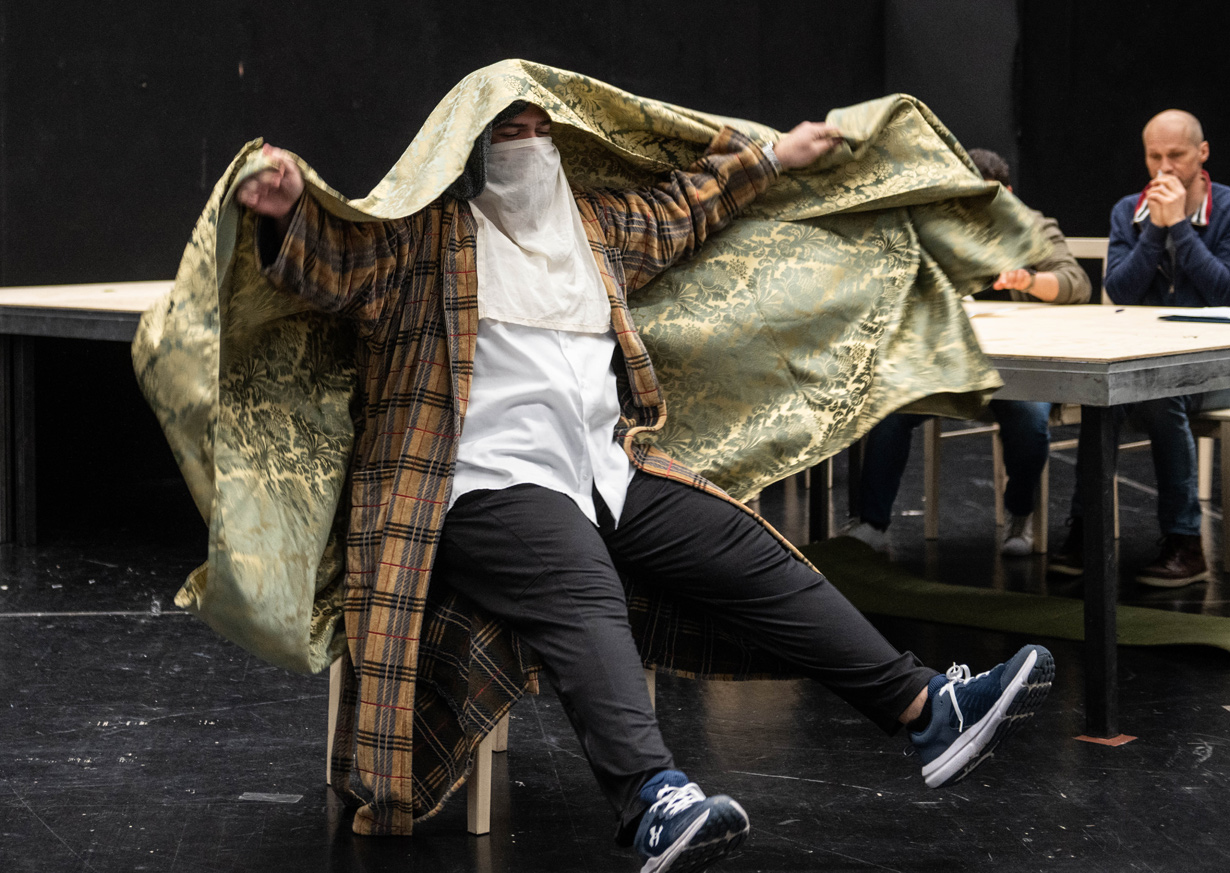

Gianni Schicchi

For the finale, the librettist Forzano started from a few brief lines of verse from Dante’s Inferno, in which the narrator encounters Gianni Schicchi in hell. Based on this material, Forzano and Puccini built a biting and entertaining one-act comic opera that draws on stock characters of the commedia dell’arte. Gianni Schicchi’s dynamic score is full of syncopated rhythms, accelerations, decelerations and a hefty dose of irony: performed in the isolation of a recital programme, Lauretta’s famous arioso ‘O mio babbino caro’ may sound like a profound plea from a suffering Puccini heroine, but taken in context, this musical moment shows us a calculating teenager expertly pouting at her father.

Coherence

For Puccini, it was important that the three works were performed together. Yet the triptych also has a performance tradition in which the individual one-acters are performed separately, or in combination with works by other composers. When performing the complete triptych, many directors look for a common thread in their stage direction that dramaturgically connects the three works. Barrie Kosky, however, explicitly chooses to embrace the episodic dramaturgy of the work rather than looking for thematic unity.

Barrie Kosky

“I like to think of Il trittico as a three-course menu, curated by Puccini”

The story

The story of Il tabarro (The cloak), Suor Angelica (Sister Angelica), and Gianni Schicchi.

The story

Il tabarro (The cloak)

Giorgetta and Michele have grown apart since the death of their child. They live on Michele’s barge, where Giorgetta embarks on a secret love affair with Luigi, one of the men who work for Michele. After a long day of labour, Giorgetta and the workers are drinking and dancing. La Frugola, the wife of the labourer Talpa, comes to pick up her husband. Together, they dream of a cottage in the countryside. In contrast, Giorgetta and Luigi long for a life in bustling Paris, the city they both come from. The lovers agree to meet up in secret that night.

Michele yearns to return to the past, when his whole family regularly snuggled up together under his large cloak. He lights his pipe. Luigi, who misinterprets this as a sign the coast is clear, returns to the barge and encounters Michele. Michele forces Luigi to admit his affair with Giorgetta, then murders him and hides the corpse under his cloak. When Giorgetta returns, he pulls his cloak aside and reveals her dead lover.

Suor Angelica (Sister Angelica)

After giving birth to an illegitimate child, Angelica was forced by her family to enter a convent. She has now spent seven years with the sisters, cut off from the world. The women’s daily lives are governed by rules, customs and rituals. Then a visitor is announced: Angelica’s aunt. She says that Angelica’s sister wants to get married and demands that Angelica renounce her inheritance. When Angelica asks about her child, her aunt tells her that her son died long ago from an illness. Angelica collapses and has a vision that shows her little son waiting for her in paradise. To join him, she drinks a poison. In the throes of death, she realises that her act of suicide will prevent her from entering Heaven and she begs the Virgin Mary for mercy.

Gianni Schicchi

Buoso Donati, a rich man, has died and is surrounded by his relatives who are feigning grief and speculating about his will. When they discover to their shock that Buoso Donati has left his entire fortune to a monastery, they refuse to accept it and look for a solution. The young Rinuccio says there is one man who can help them: Gianni Schicchi, the father of Lauretta (who Rinuccio is in love with). Cunning Gianni Schicchi comes up with an ingenious plan. Nobody outside the family knows of Buoso Donati’s death yet so Schicchi will pretend to be the dying Donati and dictate a new will. However, he leaves the most valuable and coveted part of Donati’s fortune not to the family but to himself.

Timeline

Tijdlijn

Tijdlijn

1858

Giacomo Puccini is born on 22 December in the provincial town of Lucca in Italy. His family are part of the local music scene and have produced four generations of church organists. It seems at first as if Puccini will tread in their footsteps, until he sees a production of Verdi’s Aida in Pisa in 1876. He decides to focus exclusively on opera and starts training in Milan, where he is taught by the composer Amilcare Ponchielli.

1883

Puccini composes his first opera, the one-act work Le villi, for a competition organised by the music publisher Sonzogno, but he fails to win any of the prizes. Despite this, the opera premieres at the Teatro dal Verme in Milan thanks to the support of friends and acquaintances. Sonzogno’s competitor, the publisher Giulio Ricordi, does recognise the young composer’s talent: Ricordi asks him to expand on his Le villi and commissions him to write a new opera. The premiere of Edgar in 1889 is not a success.

1893

After a difficult creative process involving four different librettists in succession, Puccini’s third opera Manon Lescaut finally premieres in Turin in 1893. The opera marked Puccini’s big international breakthrough

1894-1904

Puccini collaborates regularly, with intervening gaps of several years, with the two librettists Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa, with whom he builds up a successful oeuvre. His La bohème has its premiere in 1896, followed by Tosca in 1900. Both are global hits. Madama Butterfly gets an unenthusiastic reception at its premiere in Milan in 1904, but it too becomes a firm favourite among audiences after a few changes are made. Puccini is seen as the leading opera composer of his generation, both in Europe and on the other side of the Atlantic.

1910

After several quiet years in which he looks for interesting material, Puccini’s La fanciulla del West gets its world premiere in December 1910 at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. The premiere is a huge success: the performers are called back to take a bow no fewer than 47 times. Even so, the opera never achieves the immense popularity of a La bohème or Tosca.

1914

Giulio Ricordi dies in 1912. Ricordi had supported Puccini ever since Le villi, feeding him with ideas and mediating whenever Puccini had artistic differences with his librettists, and his death is a blow for Puccini, whose relationship with Ricordi’s son Tito is much cooler. In 1914, without consulting his publisher, Puccini accepts a commission from Vienna to compose an operetta. When the First World War breaks out and Italy joins the Allies in 1915, Puccini seeks to maintain a neutral position. As a result, the premiere of La rondine in 1917 is in neutral Monte Carlo rather than Vienna or Italy.

1918

During the war years, Puccini works on Il trittico. The triptych premieres in December 1918 at the Metropolitan Opera. In the wake of the war (the Armistice had only been signed a month earlier, on 11 November 1918), Puccini is unable to travel to New York to attend the occasion. The triple bill enjoys a warm reception but in the years that follow, the one-acters are performed individually at least as often as in combination.

1924

Puccini dies in Brussels at the age of 66 after an operation for throat cancer. He leaves his final opera, Turandot, unfinished.

2024

Dutch National Opera, which dates back to 1965, is presenting Puccini’s Il trittico as a triptych for the first time, with Lorenzo Viotti responsible for the music and Barrie Kosky for the stage direction. The opera company previously presented a double bill of Il tabarro and Gianni Schicchi in 1977, and a double bill of Gianni Schicchi alongside Zemlinsky’s Eine florentinische Tragödie in 2017. Elsewhere in the Netherlands, there have been productions of Il trittico as a whole by Opera Zuid (2007), Opera Spanga (1999), and others.

A conversation with stage director Barrie Kosky

In stage director Barrie Kosky’s interpretation of Il trittico, the three operas have nothing to do with one another, and at the same time everything. Rather than aiming for a comprehensive concept in this production, he treats each one-acter as a world in its own right.

‘Il trittico is like a three-course meal’

“These operas are very different musically and dramatically; the only thing they have in common is death. Il tabarro ends with a murder committed in a jealous rage. In Suor Angelica, Angelica commits suicide after learning her baby son died. And in Gianni Schicchi it is the death of Buoso Donati that sets the intrigue in motion. I find that connection — the presence of death in different forms — interesting, but not enough to serve as the basis for an entire concept. So I decided not to try and unify the three works in a single conceptually cohesive whole in my production. If there is anything uniting the three operas in my stage direction, it’s the design and the aesthetics. The sets have been kept plain for all three operas. We use simple ways of indicating the location, leaving plenty of room for the emotions and character development.”

Dark and light

“Puccini toyed at one point with the idea of basing all three works on Dante’s Divine Comedy and people sometimes attach a lot of importance to that fact. From that perspective, the operas are seen as a progression from dark to light: from Hell (Inferno – Il tabarro) via the Mountain of Purgatory (Purgatorio – Suor Angelica) to Heaven (Paradiso – Gianni Schicchi). But in the end, only Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi was actually based on Dante. That initial idea was just a vague sketch that Puccini never worked out in detail.”

“To my mind, this reading doesn’t do justice to the individual works. Gianni Schicchi is full of energy but it features the most horrible individuals. It is closer to Hell than Heaven. That is why my set designer Rebecca Ringst and I have created a space that in fact gets darker and darker over the course of the evening.”

Puccini as chef

“I prefer to approach Il trittico as a three-course meal prepared and cooked by Puccini as the chef. Each course offers something different: a completely new standalone assortment of flavours. In the end, it is the succession of different individual courses that makes the evening. Indeed, I believe it’s no coincidence that Gianni Schicchi is the final one of the three. It is a light dessert to complement the heavier dishes that precede it.”

Experiment

“I think Puccini saw Il trittico as an experiment. It’s as if he was challenging himself with each opera to tell a story in less than an hour that was sufficiently compact but also rich. And he succeeded impressively. In each opera, Puccini builds up another new world from scratch with its own distinctive colour and atmosphere. Each one-acter gives you the feeling you have spent at least three hours in the company of these characters – that’s how convincing his portrayals are.”

The first course: lost souls in a bleak world

“Il tabarro depicts a bleak world peopled by lost, broken souls. The opera oozes abject poverty and an overwhelming sense of desolation. Even Giorgetta and Luigi’s affair seems driven more by desperation than love. It seems for a moment as if the arrival of La Frugola will lighten the mood, but you soon realise her singing has a certain mechanical quality. She too does not feel a genuine lust for life.”

“It is striking how Puccini has inserted a clear musical echo from La bohème in his Il tabarro. That is an invitation to compare the two operas. And the contrast is indeed huge. Whereas the characters in La bohème are still resourceful, full of life and with a sense of community despite their poverty, that is far from the case in Il tabarro.”

“Il tabarro is a slow burner. As in a Greek tragedy, all the elements are carefully manoeuvred into place. In fact, not much happens in the first 55 minutes. The drama only erupts in the final three minutes, but the preceding 55 minutes are crucial, and indispensable to the impact of the opera.”

The second course: intense grief and supreme ecstasy

“Suor Angelica is perhaps the trickiest of the three operas to direct convincingly. You have singing nuns, a dead child, visions and an appearance by the Virgin Mary, so you have all the ingredients for kitsch. One of the first things I made clear about the scenography was that I didn’t want any crucifixes, nunnery doors swinging open or a blinding light in the final scene. I have no doubt that after Angelica learns her baby son is no longer alive, she loses her grip on reality. The opera turns into an extended monologue by Angelica that intermingles intense grief and supreme ecstasy — Angelica is clearly hallucinating.”

“In Suor Angelica too, Puccini makes sure to set the scene in a way that maximises the impact of the drama. I recently directed Poulenc’s opera Dialogues des Carmélites, and it is very different to Suor Angelica. In the Poulenc opera, the nuns have meaningful theological discussions with one another about divine grace and martyrdom. In Suor Angelica, the nuns talk about the most banal, trivial things. But that’s surprisingly effective: it lets Puccini show what a dull, monotonous place Angelica has been confined to for the past seven years. You feel her desperation all the more. This opera is just as bleak as Il tabarro.”

The third course: laughing about death

“The contrast between Suor Angelica and Gianni Schicchi could not be greater. After the incredible sincerity and poignancy of Suor Angelica, we find ourselves in a world where Puccini parodies and makes fun of those same emotions. Death is deprived of all solemnity in Gianni Schicchi; it becomes a tool to be used and abused. The Buoso Donati family hover round the corpse like vultures, driven purely by greed. These are monstrous, despicable creatures, yet they have a certain charm because we see ourselves reflected in them. Their avarice and grotesque traits are all too recognisable.”

“In his Gianni Schicchi, Puccini draws heavily on the commedia dell’arte tradition with its stereotypical characters, but he manages to give an updated version of the characters that is appropriate for the twentieth century. There is a clear post-Freudian feel to the interactions, and the dynamics remind me a lot of the films of Luis Buñuel. Everything happens beneath the surface and no one can stand the others, even though they are fully prepared to pretend they can.”

“It’s striking to see how Puccini mocks himself too in this opera. The famous ‘O mio babbino caro’, sung by Gianni Schicchi’s daughter Lauretta, seems at first to fit with the tradition of Puccini arias lamenting the suffering of tragic heroines. But whereas the arias sung by Mimì or Tosca come from the heart and express that sincerity, that is far from the case with Lauretta. She uses the same musical language and resources as the great Puccini heroines, but with the deliberate aim of manipulating and deceiving others. It’s a case of like father, like daughter.”

“It is my firm conviction that the power of theatre lies in the tension between sincerity and deceit. Theatre is an art form that relies heavily on artifice, but that is precisely why it can sometimes get closer to the truth than realism. Puccini too seems to have been fully aware of this in his Trittico, which is a sophisticated play on this idea.”

Dutch text: Laura Roling

Translation: Clare Wilkinson

A trilogy for eternity

Il trittico – the triptych. The term is used in art history to refer to a group of three images, paintings, carvings or sculptures that belong together or are physically connected. Triptychs are mainly found in churches as altarpieces. But now Giacomo Puccini was creating a musical ‘triptych’? The composer of realistic human dramas, the man who orchestrated the tragedies of Floria Tosca and Cio-Cio-San? How can we reconcile this apparent contradiction?

A trilogy for eternity

The composer himself preferred the name ‘triolet’ for his three one-acters, rather than Il trittico, the title proposed by his publisher Tito Ricordi — a title that is not mentioned in the piano scores, nor in the programme for the premiere on 14 December 1918 in the Metropolitan Opera House, New York. Even though the work was explicitly conceived as a trilogy, the first performance agreements were already offering the option of performing the individual one-acters separately. And it was not long before this option was being exercised. This is typical of this unusual work, which had difficulty for a long time in gaining a foothold in the opera repertoire but whose unique charms have regularly been rediscovered and are attracting increasing admiration.

As early as 1900, Giacomo Puccini had conceived the idea of composing a trilogy of three separate, independent works that would be performed together. However, his attempts to put this idea into practice were repeatedly frustrated by problems in finding the right material and, above all, the right combination. Puccini was fascinated by a concept that turned out to be incredibly difficult to realise: he wanted his three one-acters to have nothing to do with one another in terms of content or music; on the contrary, each should have its own ‘colour’ and mood. And that would constitute the unifying factor. Puccini took the three ‘colours’ from the Quartier Latin scene in his Bohème: tragic, sentimental and comic.

Il tabarro

After considering numerous possible sources and authors over the years for his first one-acter, Puccini eventually found inspiration in the theatre — as he had done with Madama Butterfly and La fanciulla del West (both based on plays by David Belasco). It was probably May 1912 when he saw the play La houppelande (The Cloak) by Didier Gold in Théâtre Marigny in Paris. The material seemed ideal for the ‘tragic colour’ he was looking for. After a couple of failed attempts to obtain a librettist, he found the perfect choice in Giuseppe Adami. With numerous interruptions — including to work on La Rondine — Il tabarro became the first of the three one-acters Puccini composed.

Puccini's librettist Giuseppe Adami kept the basic structure of Didier Gold’s shocking Grand Guignol play, as well as many telling details. However, Adami tightened up the structure and the language, and he added depth to the psychology of the characters. By the end, the libretto for Il tabarro was a better drama than Gold’s original play, even if Puccini complained at first that the language was too ‘gentle’ and not coarse enough for the social stratum these people belonged to.

Il tabarro starts with the motif that will characterise the rest of the opera: the swaying ‘river motif’ that seems archaic thanks to the church-music tonality, despite that being repeatedly disrupted by dissonances. Echoes of Claude Debussy’s music can also be heard, such as the melody in the top vocal lines that is reminiscent of Debussy’s Cathédrâle engloutie. Puccini uses this motif to build up the overture, which is unusually long for him and presages the atmosphere in the opera as an ominous sign of what is to come, as explained in the detailed notes for the stage direction.

The ‘river motif’ recurs throughout the opera in various time signatures (6/8, 9/8, 12/8). It seems to create its own time continuum, more hypnotic than calming. It can be interpreted as a melodic expression of the hopelessness, which regularly turns into a threatening feeling with the jagged interventions of the solo voices. The gritty verismo passages in the score require a car horn and a ship’s siren, which have been included in the score as meticulously as the deliberately off-key barrel organ that Giorgetta and the labourers dance to. Puccini has skilfully composed secondary scenes and comic relief scenes where the music and libretto are played off against each another with almost horrible perfection. Three numbers in particular stand out in the musical score. Luigi’s complaint lamenting the exploitation of the workers – tempered in parts and passionate in others – comes just before his duet with Giorgetta celebrating life in the Parisian quarter of Belleville. And shortly before the end, Michele sings the deep, dark monologue ‘Nulla! Silenzio!’, which Puccini composed for a performance in 1921 to replace Michele’s ode to the ‘eternal river’, which was originally performed at this point in the opera.

Suor Angelica

Suor Angelica is the only opera in the triptych with a libretto that is entirely original. It was penned by the librettist Giovachino Forzano, who was a relatively unknown author then. Puccini’s enthusiasm for a story that takes place in a convent and ends with the mystical transfiguration of the main protagonist is surprising, given the topics he had previously chosen as material for his compositions. Biographers point to Puccini’s frequent visits, just before choosing the subject for his second one-acter, to his sister Iginia, two years older than him, who had been living as an Augustinian nun for forty years by then in the Monasterio della Visitazione, close to Lucca. While searching for suitable material, Puccini also asked the playwright Valerio Soldani to send him his Margherita di Cortona again, a work the composer had rejected as an option years previously and that had similarities in its subject matter with Suor Angelica.

The opening scene shows why Puccini thought this opera would be a suitable solution to link the sombre Il tabarro and the virtuoso comic opera Gianni Schicchi: a carillon plays a melody of six notes that the strings and celesta turn into a motif played quietly that takes the audience straight to the convent cloisters. The entire first part clearly projects the ‘sentimental’ colour that Puccini had already had in mind years earlier and that he may have experienced in his personal visits to monasteries and nunneries. The scene, reminiscent of chamber music, focuses on the characters of the various nuns and reveals the nature of convent life through dialogues. The orchestral approach changes with the appearance of Zia Principessa, whose treatment by Puccini is both very skilful and threatening — a latent ominous march underlies the confrontation between her and the title character. The aunt’s admission that Angelica’s child has died is interspersed with the calm motif of three ascending triads. This is soon followed by one of Puccini’s most famous arias, ‘Senza mamma’.

The opera’s mystical finale, with its grandiose orchestration featuring organ, brass and cymbals that rhythmically echo the refrains, is often given as the reason why Suor Angelica was the least popular of the three Trittico one-acters among the general public. The ‘musician of little things’, as Puccini once described himself, had strayed too far from his natural habitat with this subject matter and this musical treatment. Puccini himself made few changes to the work after its premiere. In 1921, he complained in a letter to Sybil Seligman about the publisher Ricordi consenting to a production of Il tabarro and Gianni Schicchi without Suor Angelica: “It truly saddens me to see the best of the three operas being rejected. In Vienna, it was the most effective of the three...”

Gianni Schicchi

Gianni Schicchi, the final work, soon became the most popular of the three Trittico one-acters and enjoyed a life of its own on the opera stage, much to the chagrin of the composer. More so than the other two works, Schicchi was performed alongside other one-acters. The Metropolitan Opera in New York, for instance, the venue for the triptych’s world premiere, was soon performing Schicchi together with Richard Strauss’ Salome. Even so, the ‘comic element’ was the hardest material for Puccini to find for his envisaged trilogy. The main source is Dante’s Commedia, specifically the thirtieth canto of his Inferno. Another important source for the opera is comments by an anonymous Florentine author of the fourteenth century that gives additional details on the Gianni Schicchi story.

Gianni Schicchi stays true to its origins in commedia dell’arte. Schicchi is the classic cunning and comic harlequin surrounded by a cast of similarly classic commedia characters, such as the amorosi Rinuccio and Lauretta, the vecchi Simone and Zita, plus a doctor and a notary. Musically, it is almost as if Giacomo Puccini had developed his own tailored form for his comic opera, so successful was he in composing an astonishingly amusing score.

Even the syncopated, wild ‘tumultuoso’ at the start seems irrepressible: when the solo violin seems to be calling for a moment of reflection with a ritardando, the flutes suddenly come in with a motif that is simply too exuberant to be played slowly. Only the snare drum manages to rein the orchestra in, but the funeral march it leads soon descends into a parody thanks to the rhythmic moaning of the family in a masterly rapid interchange of dialogue between the orchestra and the mourning relatives. This extremely demanding score, which constantly has the orchestra interacting with the scene and the characters, incorporates the solo numbers perfectly into the musical comedy. Lauretta's arioso ‘O mio babbino caro’ combines vocal gentleness with suicidal threats and challenges us to unearth the secret behind the desperation of Gianni Schicchi’s daughter with her pleas for “mercy” in A minor. ‘Addio Firenze’ is a masterpiece, sung mainly by Gianni Schicchi. The sentimental melody accompanied by cellos and emphasised by muted trumpets sounds like an ode to Schicchi’s birthplace, oscillating between melancholy and kitsch, but even if you were not paying attention during the short exposition, you cannot fail to hear of cherished Florence being waved goodbye “with this stump”. The song aims to remind the relatives of their complicity, which could lead them to losing a hand and being banished if the treachery were to be discovered. Indeed, the melody is intoned repeatedly as a kind of parodic leitmotif, and it is deployed particularly skilfully in grotesque fragmentation in the Will scene. This and the many other astoundingly comical musical ideas make Gianni Schicchi an exceptional work, and not just in the context of Puccini’s oeuvre.

By deciding to end his trilogy with a comic work, Puccini seems to be inventively mirroring the origins of European theatre: after all, it was customary during the great Dionysia festivals of Athens around 500 BCE to end the tragedy days with a light-hearted satirical work.

Puccini’s concept of the one-acter is undeniably an explicitly modern theatrical experiment. In his Puccini biography, Dieter Schickling notes that the composer’s constant preference for an episodic dramatic treatment reached its high point with Il trittico. In that sense, the work is closer to Alban Berg’s Wozzeck than to one-acters like Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana or Richard Strauss’ Salome and Elektra. Of course, it is not sacrilege to combine Il tabarro, Suor Angelica or Gianni Schicchi with works by other composers if that is based on an inspired judgement; this has been done many times before and continues to be done. However, Puccini’s exceptional episodic mood drama deserves constant reassessment and now, over a hundred years after its world premiere, it has more than earned a permanent place in the opera repertoire.

Text: Nikolaus Stenitzer

Success!

From now on you will receive our performance updates.

Something went wrong

Something went wrong, please try again later. Apologies for the inconvenience.