Die Zauberflöte

Performance information

Voorstellingsinformatie

Voorstellings-informatie

Die Zauberflöte

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

Duration

3 hours and 15 minutes, including one interval

This performance is sung in German, with Dutch and English surtitles.

Singspiel in two acts (KV 620)

Makers

Libretto

Emanuel Schikaneder

Musical direction

Riccardo Minasi

Stage direction

Simon McBurney

Set design

Michael Levine

Costumes

Nicky Gillibrand

Lighting design

Jean Kalman

Video

Finn Ross

Sound design

Gareth Fry

Dramaturgy

Simon McBurney

Klaus Bertisch

Staging

Rachael Hewer

Cast

Sarastro

Christof Fischesser

Tamino

Mingjie Lei

Der Sprecher

Frederik Bergman

Königin der Nacht

Rainelle Krause

Pamina

Ying Fang

Papageno

Thomas Oliemans

Monostatos

Lucas van Lierop

Papagena

Laetitia Gerards

Zweiter Priester / Erster geharnischter Mann

Marcel Reijans

Erster Priester / Zweiter geharnischter Mann

Mark Kurmanbayev*

Erste Dame

Sophia Hunt*

Zweite Dame

Martina Myskohlid*

Dritte Dame Esther Kuiper

* Dutch National Opera Studio

Netherlands Chamber Orchestra

Chorus of Dutch National Opera

Chorus master

Edward Ananian-Cooper

Co-production with

English National Opera, Londen Festival d’Aix-en-Provence

Production team

Assistant conductor

Boudewijn Jansen

Assistant director

Annemiek van Elst

Maarten van Grootel

Assistant director during performances

Annemiek van Elst

Movement staging

Jessica Angleskhan

Stunt coach

Femke Luyckx

Rehearsal pianists

Nathalie Dang

Jan-Paul Grijpink

Amy Chang

Daniel Ruiz De Cenzano Caballero

Language coach soloists

Miriam Kaltenbrunner

Language coach chorus

Cora Schmeiser

Assistant chorus master

Ad Broeksteeg

Stage managers

Joost Schoenmakers

Pieter Loman

Niek Stroomer

Artistic planning

Margot Vervliet

Production management orchestra

Rugiero Vitalis

Associate lighting designer

Mike Gunning

Associate video designer

Jane Michelmore

Associate sound designer

Matthieu Maurice

Costume supervisor

Mariama Lechleitner

Master carpenter

Peter Brem

Lighting manager

Coen van der Hoeven

Lighting operator

Jasper Paternotte

Props master

Jolanda Borjeson

Special Effects

Peter Visser

Platform operator

Emiel Duijves

First dresser

Jenny Henger

First make-up artist

Pim van der Wielen

Sound technician

Florian Jankowski

David te Marvelde

Gerco van Veenen

Video operator

Erik Vrees

Surtitle director

Eveline Karssen

Surtitle operator

Maxim Paulissen

Head of Music Library

Rudolf Weges

Set supervisor

Puck Rudolph

Gerko Min

Production management

Lotte Heeman

Chorus of Dutch National Opera

Sopranos

Lisette Bolle

Taylor Burgess

Jeanneke van Buul

Caroline Cartens

Nicole Fiselier

Deasy Hartanto

Oleksandra Lenyshyn

Simone van Lieshout

Tomoko Makuuchi

Vesna Miletic

Sara Pegoraro

Jannelieke Schmidt

Altos

Elsa Barthas

Daniella Buijck

Rut Codina Palacio

Johanna Dur

Yvonne Kok

Fang Fang Kong

Myra Kroese

Itzel Medecigo

Sophia Patsi

Marieke Reuten

Carla Schaap

Klarijn Verkaart

Tenors

Wim-Jan van Deuveren

Frank Engel

Milan Faas

Ruud Fiselier

Cato Fordham

Dimo Georgiev

John van Halteren

Stefan Kennedy

Robert Kops

Tigran Matinyan

Frank Nieuwenkamp

Dean Parker

Richard Prada

François Soons

Jeroen de Vaal

Basses

Ronald Aijtink

Jorne van Bergeijk

Nicolas Clemens

Jeroen van Glabbeek

Agris Hartmanis

Hans Pieter Herman

Sander Heutinck

Tom Jansen

Dominic Kraemer

Matthijs Schelvis

Jaap Sletterink

Berend Stumphius

Harry Teeuwen

Foley artist

Ruth Sullivan

Video artist

Blake Habermann

Knaben

Nationale Koren (part of Vocaal Talent Nederland)

Staging

Irene Verburg

Jelle Wolfert

Syl Becht

Wourick de Boer

Jonne Stallenberg

Lucas van ’t Hof

Marwan Linders

Jonathan Hoffmann

Midas Engelbrecht

Mil Blindenbach

Actors

Rowin Prins

Jorge Arbert

Alexander de Vree

Erik van Welzen

Marty Keiser

James Owen Dunn III

Judy Lijdsman

Karin van der Hilst

Lieke Gorter

Julia Cavagna

Natalie Saibel

Gabriella Schmidt

Netherland Chamber Orchestra

First violin

Cécile Huijnen

Tijmen Huisingh

Melissa Ussery

Beverley Lunt

Philip Dingenen

Kilian van Rooij

Marijke van Kooten

Vanessa Damanet

Maaike Aarts

Inês Costa Pais

Second violin

Laura Oomens

Olga Caceanova

Maria Gilicel

Catharina Ungvari

Siobhán Doyle

Stephanie van Duijn

Inge Jongerman

Natasa Grujic

Viola

Luba Tunnicliffe

Berdien Vrijland

Anna Jurriaanse

Minna Svedberg Feldtmann

Fiachra de Hora

Elias Zaabi Saez

Cello

Sietse-Jan Weijenberg

Jan Bastiaan Neven

Anastasia Feruleva

Charles Watt

Double bass

Annette Zahn

Lucía Mateo Calvo

Flute

Hanspeter Spannring

Elke Elsen

Oboe

Toon Durville

Danielle Kreeft

Clarinet

Rick Huls

Peter Cranen

Bassoon

Margreet Bongers

Dymphna van Dooremaal

Horn

Fabio Forgiarini

Fred Molenaar

Trumpet

Gertjan Loot

Nicolas Isabelle

Trombone

Joren Elsen

Joao Mendes Canelas

Joost Swinkels

Timpani

Theun van Nieuwburg

Glockenspiel

Jan-Paul Grijpink

Die Zauberflöte in a nutshell

In het kort

Die Zauberflöte in a nutshell

From child prodigy to established composer

Mozart was born in 1756 as the youngest son of Leopold Mozart, a renowned composer, violinist and teacher from Salzburg. From the age of three, Wolfgang sat in on the piano lessons of his older sister Nannerl, and he was soon playing the piano himself to a high standard. Their father took the two child prodigies on tours of Europe. In the course of his brief life, Mozart managed to compose an extensive oeuvre, with opera occupying a significant position alongside chamber music, piano concerts and symphonies. The final year of his life was one of his most fertile, in which he composed two operas, the last one being Die Zauberflöte.

Mozart and Schikaneder

Mozart and Emanuel Schikaneder, famous in his day as a playwright, actor and impresario, may have first met in 1780 when Schikaneder and his theatre company were in Salzburg. In 1789, Schikaneder was put in charge of the Theater auf der Wieden in Vienna, where Mozart was a regular visitor. Schikaneder produced various fairy-tale operas, which were a popular genre. In line with this trend, in early 1791 Schikaneder offered Mozart the libretto of Die Zauberflöte. Mozart got to work composing the music, and the opera premiered on 30 September 1791. Mozart died just two months after the premiere.

The Enlightenment, Freemasonry and Ancient Egypt

In the 1780s, both Mozart and Schikaneder joined the Freemasons. The symbolism of the Freemasons, with its Enlightenment connections, was a major source of inspiration in the creation of Die Zauberflöte. Good versus evil and light versus darkness are central contrasts in the opera. Images from ancient Egypt were another source of inspiration for Mozart and Schikaneder, and although Egypt is never mentioned by name, the libretto does refer to temples, pyramids and Egyptian gods. However, recent research has shown it is unlikely either Mozart or Schikaneder intended Die Zauberflöte to be an allegory of Freemasonry.

Die Zauberflöte as an inspiration for many others

After Mozart and Schikaneder, many composers, writers and other artists took up the subject matter of Die Zauberflöte. The first to do so was Schikaneder himself, who created a sequel to Die Zauberflöte in 1798, in partnership with the composer Peter Winter. In 1802 Johann Wolfgang von Goethe published a text that was a follow-up to Die Zauberflöte, although it was never put to music. Both Richard Wagner and Richard Strauss also found inspiration in Die Zauber- flöte, Wagner for Parsifal and Strauss for Die Frau ohne Schatten. The opera is now more than 200 years old, yet its interpretation is still the subject of lively debate among musicologists, performers, researchers and the general public.

Die Zauberflöte as a problematic work

The text of Die Zauberflöte dates from a period when terms and attitudes we now find inappropriate or even offensive were commonplace. Directors and theatremakers have dealt with this in various ways through the years. In McBurney’s production, a number of amendments have been made to the texts as sung and spoken, while still remaining as faithful as possible to the original text.

Simon McBurney’s imaginative direction

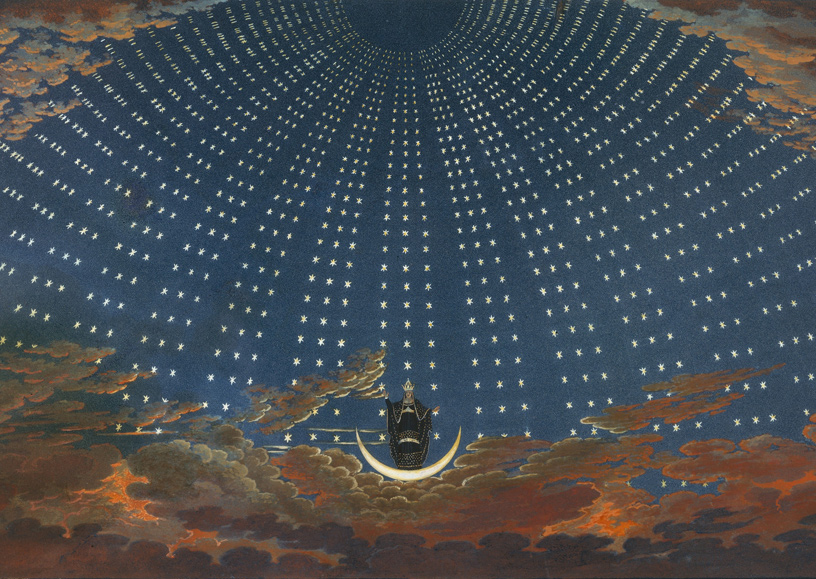

In 2012, the stage director Simon McBurney created a new production of Die Zauberflöte for Dutch National Opera. He kept the opera’s fantastical elements while at the same time questioning the Enlightenment rhetoric, questions that can also be seen in Mozart’s music. Moreover, McBurney’s production takes a critical look at the position of women in the opera. McBurney’s theatre operates like an open book: by revealing the technology behind certain aspects, he actually accentuates the opera’s magic.

The story

Het verhaal

The story

I.

Prince Tamino is fleeing a serpent and ends up in the kingdom of the Queen of the Night. He is saved by her three Ladies. The Queen concocts a plan: perhaps this young prince could free her daughter Pamina from the clutches of the evil Sarastro. When Tamino revives, he meets the bird-catcher Papageno, who tells him that he himself was the one who defeated the serpent. The three Ladies return and put a padlock on Papageno’s mouth as punishment for his lies. They give Tamino a portrait of Pamina. Tamino falls in love at first sight and promises to free her.

Papageno is sent along with the prince and is given a set of chiming bells as an aid. Tamino gets a magic flute. Both instruments are capable of transforming the mood of humans and animals. They will also get the assistance of three boys.

In the kingdom of Sarastro, Papageno finds Pamina first. She is being assaulted by Sarastro’s servant Monostatos. After Monostatos runs away, Papageno tells Pamina about the prince who will soon be here to save her. Elsewhere in the kingdom, Tamino comes across a priest in the Temple of Wisdom who says Tamino is wrong to curse Sarastro and his accusations are groundless.

At a grand ceremony, Sarastro appears, and Tamino and Pamina see one another for the first time. When they fall in each other’s arms, overcome by love, they are pulled apart as Tamino has to undergo a number of ordeals first.

II.

The ordeals start. After having also been promised a wife, Papageno joins Tamino. The trial of silence that is imposed on them both is broken almost immediately by Papageno, much to Tamino’s annoyance. Monostatos attempts to assault Pamina while she sleeps, but is interrupted by the Queen of the Night, who calls on her daughter to take revenge on Sarastro. However much Pamina loves her mother, though, she is not prepared to kill him. After Monostatos makes yet another attempt on Pamina, he is chased off by Sarastro. The king comforts Pamina and assures her there is no place in his kingdom for revenge, only for understanding and forgiveness.

Tamino and Pamina are reunited, but because Tamino is still bound by silence Pamina thinks his love for her has gone. She is so distraught she wants to kill herself, but the three boys prevent her from doing so. The two lovers are reunited again; this time they can talk to one another as Tamino has completed his trial of silence. They undergo the final two trials together. Given that Papageno did not successfully complete his trial, the woman promised to him − Papagena − is taken away from him as soon as he makes her acquaintance. His attempted suicide is prevented by the three boys and eventually, he and Papagena are reunited. The Queen of the Night tries to enter Sarastro’s temple with her entourage but is defeated for good. Tamino and Pamina are honoured as a couple who have withstood all the ordeals thanks to their love.

Die Zauberflöte in years

Die Zauberflöte in jaartallen

Die Zauberflöte in years

27 January 1756

Mozart is born in Salzburg as the seventh child of Leopold and Anna Maria Mozart. Of the seven children, only Wolfgang and his older sister Maria Anna, also known as Nannerl, survive beyond twelve months. Their father Leopold is a celebrated violin teacher and composer. Nannerl gets her first piano lessons from her father when she is seven, and three-year-old Wolfgang watches her in fascination. Wolfgang too masters the piano in no time, and he starts composing at a young age.

1762-1773

From the age of six, Wolfgang is taken by his father on concert tours across Europe with his sister Nannerl. Wolfgang the child prodigy performs in cities from Milan to The Hague. During these tours, Wolfgang composes his first symphonies. He undertakes his first attempts at opera in his early teens.

1785

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, now a celebrated composer, joins a masonic lodge in Vienna. Another Viennese masonic lodge includes among its members Emanuel Schikaneder, a German impresario, playwright, actor, singer and composer. Schikaneder certainly met Wolfgang in 1780 when he stayed in Salzburg and was a frequent visitor to the Mozart family home. Schikaneder’s theatre company often performed Mozart’s operas.

1789-1791

After spells in various places in southern Germany, Schikaneder is put in charge of his own theatre in Vienna, where he establishes a new company. The Theater auf der Wieden becomes known for its ‘magical operas’, with Wolfgang regularly in the audience. The friendship between Mozart and Schikaneder results in several collaborations. In the spring of 1791, Schikaneder writes the libretto for Die Zauberflöte and asks Mozart to compose music for it. Wolfgang probably starts work on the composition in April.

30 September 1791

Mozart puts the finishing touches to the overture just two days before the premiere of Die Zauberflöte. The opening night is a resounding success. In the ten years that follow, the opera will be performed no fewer than 233 times in the Theater auf der Wieden. Mozart does not live to enjoy this lasting success as he dies two months after the premiere, on 5 December 1791. Die Zauberflöte is his last opera.

1794

Die Zauberflöte is performed for the first time in Amsterdam. It is followed in 1799 by the first performance in a Dutch translation, De Toverfluyt. As well as the performances in Amsterdam, the opera is soon to be heard throughout Europe, and it would remain a fixture of the opera repertoire.

1882

Richard Wagner completes his final “Bühnenweihfestspiel” (Stage Dedication Festival Play) Parsifal, which draws inspiration from Die Zauberflöte. The initiation rituals and the character of the main protagonist Parsifal in particular recall Mozart’s opera.

1919

Premiere of Die Frau ohne Schatten, an opera by Richard Strauss with a libretto by Hugo von Hofmannsthal. Their aim in creating this work is to give the world a new Zauberflöte and present real life in symbolic form.

1954

Die Zauberflöte is performed for the first time by Stichting De Nederlandse Opera, the forerunner of Dutch National Opera. The conductor is Josef Krips; Georg Hartmann is responsible for the stage direction.

2012

After numerous other productions of the opera, Simon McBurney’s production of Die Zauberflöte premieres at Dutch National Opera on 6 December 2012. This particular production has remained popular ever since, with reruns at Dutch National Opera in 2015 and 2018 as well as performances around the world, including recently at the Metropolitan Opera in New York.

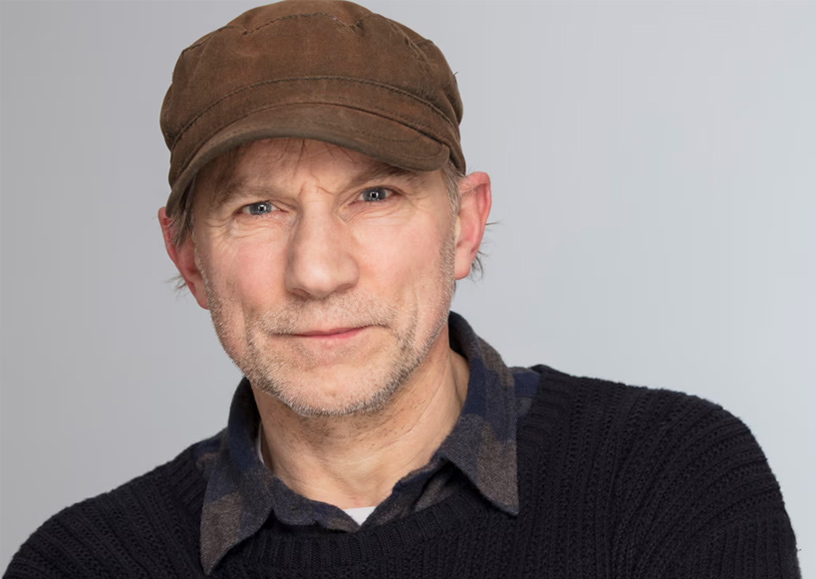

In conversation with Riccardo Minasi

In gesprek met Riccardo Minasi

In conversation with Riccardo Minasi

Maestro Riccardo Minasi, who is at the head of the Netherlands Chamber Orchestra for this production, is one of the most asked Mozart conductors of our time. Right before coming to Amsterdam, he conducted the Berlin Philharmonic in an all-Mozart programme.

You are one of the most asked Mozart conductors of this moment. What makes you keep coming back to Mozart's work?

“He’s a composer that I adore with all my heart and I’ve been listening to and studying forever. I have done almost all his operas, but never Die Zauberflöte, so it’s an absolute pleasure to be here! Mozart is not my exclusive music love, however. Last season I performed a large range of repertoire, from Medieval music to new commissions, so I’m trying to do everything.”

Die Zauberflöte is different from Mozart’s late operas because he went back to the genre of the Singspiel after he wrote the Da Ponte operas. What makes Die Zauberflöte musically so different?

“I think it’s the most complete opera he ever wrote, a sum of all the experiences he gained in his regrettably brief life. The exceptional formal diversity within Die Zauberflöte is outstanding. Just have a look at the beginning of the opera: the overture commences with a slow French opening followed by a fugue, the highest and most noble of musical forms. Then a quite conventional Italian opera seria “aria di furore”, which is abruptly interrupted by a march, leading into a “farsa” inspired by the opera buffa tradition. After this initial patchwork, we come across a folk song from South-Tyrol and a love romanza. The unique assortment of forms in this first section is absolutely unique, yet even more remarkable is the coherence that emerges from this seemingly crazy variety of forms. It’s an outstanding manifesto of the most universal and esoteric principle of the Age of Enlightenment: freedom. Schikaneder, the ideator, principal craftsman and librettist of Die Zauberflöte, exerted a profound influence in the realization of this magnificent creation.”

A lot of meaning has been assigned to Die Zauberflöte, but what does the score tell you?

“The speculations about the inner meaning of the piece are countless and have also often been most imaginative. However, there exists a risk of oversimplification when reducing the libretto merely to a dichotomy of good and evil, obscuring a more nuanced comprehension of the plot. The ambiguity of the majority of the characters, the overturning and interpenetration of the situations and the difficulty distinguishing what appears to be from what actually is, are the keys to the message that Schikaneder and Mozart wanted to transmit to us.”

“In certain traditions, the awareness that a balance of a divine construction can only exist in the presence of two poles in contraposition is a well-rooted topic. And for sure it was at the base of the organization of the most liberal movements of the time, to which both Mozart and Schikaneder belonged. Their target was to transmit a tradition and self-awareness, aiming to enhance society through the cultivation of heightened individual knowledge rather than through political impositions and constraints.”

If we are not talking about good or bad but more about poles, what does this say about the world of Die Zauberflöte?

“In Cabala’s Tree of Life, the left “feminine” branch, which is dark like the Queen of the Night, is in contraposition with an active “masculine” one on the right, bright like Sarastro. They don’t have a stamp of positivity or negativity, but are rather integrated in each other, analogous to the interplay of Yin and Yang; their coexistence is essential despite their ambiguities. Ambiguity permeates every facet of the libretto, including the metaphor of rediscovered childhood innocence embodied by the three Boys. While their goodness is evident, the enigma lies in their affiliation—with the Queen. The journey that Tamino is undertaking is part of a process that cannot be explained simply by the goodness of Sarastro and his associates. These are the people that in some manner, safeguard a tradition disrupted by the imbalance in nature following the death of the Queen's husband. After his death, the Solar disc, the symbol of wisdom and the universe, went to those keeping guard of the tradition. But how can Tamino accomplish the goal of the reintegration of the poles and the resolution of the problems caused by the rupture with nature? By the conciliation with himself, with the divine, and by an order rooted in the recuperation of compassion, sharing and unity. Separation, impositions, privileges, arrogance, fear and egotism should not exist anymore.”

How do we place Papageno in this picture?

“Papageno is the emblem of the ordinary man, who is joining Tamino on his quest. Though lacking in the prince's cultural refinement, he possesses the ability to express emotions through music—an epitome of ultimate freedom. His glockenspiel acts upon the realm of emotions, facilitating dialogue between entities that would otherwise remain uncommunicative. Its sound will lead him too into a balance of nature, but transmuted into an essence of pure desire personified by Papagena. Notions, experiences and cultural preparation are the necessary conditions for accessing higher knowledge, but they inevitably culminate in an encounter with fear. What Tamino seeks is true salvation from fear, from the snake of the beginning. In this existential challenge, Papageno is much better equipped than Tamino at that point. When Tamino asks when the obscurity will disappear, the reply, "soon or never," encapsulates the enigmatic nature of his odyssey.”

What is the role of love and music in this context?

“In his journey, Tamino's motivation emanates not from a desire for glory or ambition, but from a profound love for Pamina, with whom he’ll be able to re-establish the state of nature that existed between the Queen and her husband. She’s the key that allows Tamino to find forces to move on. In fact, he plays the flute only when he understands that Pamina is alive. He creates music with a flute that drags him out of a state of despair when he finally finds inspiration and when he feels the need to create. In a metaphorical parallel, Tamino assumes a role akin to a divine creator on a miniature scale. His creative act becomes intrinsically meaningful, mirroring the broader significance of creation itself. Consequently, the essence of life for Tamino—and by extension, humanity—lies in the act of creation, with the flute serving as a symbolic vehicle for the alchemy of consciousness, embodying the union of the four elemental forces.”

As you said, there is a lot going on in Die Zauberflöte. Our three main characters, Tamino, Papageno and Pamina, keep on asking themselves “Wo bin ich?”. They are lost, they don’t know where they are. What does this say about the world, or at least the world of Die Zauberflöte?

“It’s all about uncertainty, the fact that we are all lost, even today, and that we’re constantly in search of something and not even completely aware of our full abilities. Everything that surrounds us is just pure illusion. We are all used to considering true what only appears to us. In order to control a society, it is sufficient to create just an appearance to satisfy all needs. The world that comes out from it, allegorical yet concrete, delves into the fundamental questions of humanity: for example, when Pamina guides Tamino through the final trials, encouraging him to play the flute to confront his fear of death, or more precisely the loss of materiality. The flute is the secret: with artistic expression, it is possible to overcome death, by believing in your own feelings. Who has no fear of death is alive, the one who fears death is already deceased.”

With all this musical variety, do you see Die Zauberflöte as Mozart's most revolutionary opera?

“The musical material implied is always extremely creative and his compositional strategies, with an extremely wise use of harmonical formulas that move everyone, are absolutely outstanding in this piece. I’m convinced that the musical revolution usually ascribed to Beethoven already started in Salzburg, and its pinnacle culminates in Die Zauberflöte!”

Mozart’s letter to his wife

Brief van Mozart aan zijn vrouw

Mozart’s letter to his wife

[Vienna, 7 and 8 October 1791]

Friday, half past ten in the evening

Darling, dearest wife!

I’ve just come back from the opera. It was as full as ever. The ‘Mann und Weib’ duet etc. and the bells in the first act got an encore as usual, as did the trio with the boys in the second act. But it is the quiet approbation that best pleases me. You can really see this opera is rising rapidly and steadily in people’s estimation.

Now something about what else I have been doing. Immediately after you left, I played two games of billiards with Mr Mozart (the one who wrote the Schikaneder opera). Afterwards I sold that old horse for 14 ducats; then I asked Joseph to tell Primus* to get me some black coffee, with which I smoked a wonderful pipe; then I wrote the instrumentation for nearly all of Stadler’s rondo. In the meantime, a letter arrived from Prague from Stadler. The Duscheks are all doing fine. I got the impression they haven’t had a single letter from you, although I can hardly believe this. Enough! They have all heard about the fantastic reception of my German opera. The strangest thing is that on precisely the same evening that my new opera was performed to such appreciation, Tito played for the last time in Prague with amazing applause for each number. [...]

*‘‘Primus’ was the nickname given to Joseph Deiner, a waiter in a local inn.

At half past five I went out through the Stuben Gate and did my favourite walk through the Glacis to the theatre. What do I see? What do I smell? There is Don Primus with the cutlets! Che gusto! I’m eating them now, to your good health. The clock has just sounded eleven — perhaps you are already asleep? Sh! Sh! Sh! I won’t wake you up!

Saturday the eighth. You should have seen me yesterday evening sitting at dinner. I couldn’t find the old cutlery so I just took out the silverware decorated with snow flowers and put the double candlestick with the wax candles in front of me. [...] You will undoubtedly be out swimming while I write this letter. The hairdresser came at precisely six o’clock. Primus had already lit the stove at half past five and woke me at a quarter to six. Why must it be raining again? I was so hoping you would have good weather. Make sure you keep nice and warm so you don’t catch cold. I hope the bathing will have given you a good winter — because your health was the only reason I persuaded you to take the waters in Baden. I feel so lonely without you. I had expected that. If I hadn’t had anything to do, I would have gone with you for eight days without hesitation, but there aren’t the facilities there for me to work properly and I want to avoid us getting into money difficulties; there is nothing finer than living a comfortable life and for that you have to work hard, which I am happy to do.

Box ...’s ears a couple of times on my behalf and I’d like to ask ... (who I send a thousand kisses) to give him a couple too — for heaven’s sake, make sure he doesn’t come short in this regard. The last thing I would want is for him to accuse me today or tomorrow of you not handling and caring for him properly — better to give him too many blows than too few. It would be good if you could scratch his nose, bash out an eye or cause some other visible injury so that chap will never be able to deny he got something from you. Farewell, my dear wife! The coach is about to leave. I really hope I will get a letter from you today and in that cherished hope, I kiss you a thousand times and remain forever your loving husband.

W. A. Mozart

Based on a translation from the German into Dutch by Lucas Bunge

Silent approval

Simon McBurney on Die Zauberflöte [The Magic Flute]

Silent approval

Simon McBurney on Die Zauberflöte [The Magic Flute]

On 7 October 1791, Mozart, having just returned from a performance of The Magic Flute, writes to his wife Constanze that despite the house being full, and despite listing all the numbers that were given an encore, '... what always gives me the most pleasure is the silent approval'. Silent approval is not necessarily the first thing you associate with The Magic Flute. Laughter, applause, people singing along, perhaps, but silence?

Layers and confusion

Rehearsing The Magic Flute is like conducting an archaeological excavation. The more layers you uncover the more artifacts are revealed. But making sense of what you find is the hard part. Nothing is what it seems. One landscape rolls back to reveal another: The sorrowing mother turns out to be a vengeful harpy; the horrible abductor of her daughter is more of an encouraging godfather than a despot, even if he does exercise total power over his people. But if he is a despot, then he is one who believes in wisdom and care - but with an assistant who is a rapist. In this strange world, as remote as Prospero's island, boys are wise men, and grown men have no wisdom at all. The women are abused, but Pamina, the woman at the centre of it, is the one person who has the strength and intelligence to hold the whole thing together: Here, even if the jokes are not really funny, the most comic character is the most moving. And if the landscape is strange, the story is even more eccentric.

‘Can you fix it?’

‘Well, we could put this piece of Papageno's dialogue later and that would clarify the story...’

‘Wait, no, hang on, I wasn't talking to you.’

‘We have a problem with the story here...’

‘I know, but wait... quite quickly after it starts the forward movement seems to get out of control...’

‘Yes, that's exactly what is happening with the narrative...’

‘No, no, please... wait! I am talking to the technical team about the movement of this piece of stage machinery... not about the bloody story.’

‘Yep... but you have to deal with it because it doesn't make sense...’

This is how it is in rehearsal. The moment you break, multiple conversations begin overlapping and colliding. Misunderstandings everywhere. Chaos.

On this particular day, I am watching as the movement of the stage machinery gradually gets more and more out of control. The other conversations are flying at me simultaneously, creating a kind of turbulence that I have no way of controlling. The movement gets out of control because it is chaotic, explains one of the incredible technical stage managers. He is pointing at the winch mechanism. The moment it is set in motion, the movement loops and simply gets worse and worse. It is sensitive to the initial conditions, and if there is a tiny instability, it gets in a loop it cannot get out of.

‘Ah’ I reply.

‘It is all about how it begins,’ he says.

'It is all about how it begins; I repeat to myself, as the singers and actors leave the room for a coffee. 'Sensitivity to the initial conditions'. In chaos theory, 'an arbitrarily small perturbation of the current trajectory may lead to significantly different future behaviour.' Or to put it another way, when you begin, any disturbance will mean you have no idea what chaotic thing you will end up with. Like the weather. We really have no idea where it comes from and what it will do next. Yet it seems to have its own pattern and logic. Like The Magic Flute. Sometimes illogical, occasionally unfathomable, and in places even unintelligible, nevertheless it has its own pattern and logic. When it works, you do not always know why.

Bringing order

I throw some more coffee down me as I remember how difficult it is to tell the story to someone, let alone perform it. And believe me, for the past year I have tried on numerous occasions to tell the story to friends who do not know the opera. Simply to bring some order to my thinking about it.

‘It's a kind of fairy story.’

‘Kind of?’

‘Yes, well other stories are in it too’

‘Ok so...?’

‘It begins with a guy being chased by a snake... ’

‘Cool.’

But within minutes I am out of control... I glance up at my friend who I am telling this to, as I begin to grind through the first few events. I have not even got into the arrival of the Queen of the Night. I try another tack.

‘Well... let just say it's shot full of really fascinating stuff. .. the number three, for instance, is key. ’

‘Three’

‘Yeah, well, three is amazing. It's the smallest odd prime, you know? DNA has a triplet system... I mean, it's incredible, we are hard-wired for the number three: it's set into our genetic code and permeates all levels of our culture and, and, and... (I am starting to gabble now as I see his eyes glaze over) there are three main Abrahamic religions, after all, Judaism, Christianity and Islam... Jesus rose from the dead on the third day... there are three wise men... and in The Magic Flute three is everywhere: there are three ladies, three boys, three priests, the whole opera begins with three chords in the key of E flat major (I throw in airily), E flat major has three flats in it and... ’

‘Well, sounds gripping, interrupts my friend suddenly. I can see you've got your work cut out. Good night, sleep well. See you for breakfast. ’

Three artists

I look around at the mad activity of our rehearsal room. What must it have been like with all of them in their room in 1791, in Vienna? Emanuel Schikaneder and Carl Giesecke (the librettists) and Mozart. Surely a kind of chaos with these three (yes, three of them) who were as unexpected as the piece they wove.

Carl Ludwig Giesecke, the famously women-hating polymath who originally played the First Slave, who left Vienna in a hurry and ended up as a mineralogist, rowing round Greenland in an umiak. An umiak is an Inuit boat, made and used by women, constructed out of driftwood, antler and stretched hide. A paradox for an undistinguished Viennese misogynist! that it should be a vessel constructed for and by women that saved his life on more than one occasion.

Emanuel Schikaneder, builder of the Theater an der Wien, one of the greatest men of the theatre of his time; and famously unreliable, constantly unfaithful to his wife, sculpting, rewriting and creating this piece about fidelity, harmony, truth and friendship. At the end of his life, he put Beethoven in a fiat above the theatre and paid him to write an opera, all the white haranguing him, to write faster. 1Mozart could write an overture in a couple of days,' he would yell.

And Mozart. Dying. Writing to Constanze, full of irony about this new opera he had composed, yet delighted by its success - the fact that ‘...you can see it [The Magic Flute] really becoming more and more respected and esteemed'. Just months earlier; it has been suggested, that he would have rather made an opera using The Tempest. And surely The Tempest is everywhere in the Flute: Sarastro is so like Prospero, Tamino is Ferdinand, Pamina is Miranda, Monostatos is a relative of Caliban, the Three Spirits are Ariel-like spirits...

Magic

In the rehearsal room before the singers and actors return from their coffee, my mind continues to whirl with its own unending turbulence. Okay, so it is called The Magic Flute. So it has to be magic. And there must be a flute. And why a flute? I think about a rock shelter in north-western Libya. Near the Mediterranean, called the Haua Fteah. My father; who was a prehistorian, excavated it in the early 1950s and discovered it had been occupied by humans, without interruption, for 90,000 years. And in the layer dated to 35,000 years ago, he uncovered a bone. Hollow. A fragment Bu,r.,-,1ith a hole in it. And another half-hole at the break. A bone flute. Perhaps the world’s oldest existing instrument. So the flute was one of the first instruments. A harnessing of human breath. Elemental. Mythic. And the magic? Magic is about change. Changing something into something else. Making things appear; and disappear. It is always easier to tell all you want to tell. whe,n you tell a story that involves magic. Because we all know it is not ‘real'. But of course, through the non-reality of the ‘fairy tale' we can recognize the true reality of our world. The psychological and symbolic meaning of fairy tales is well documented. It can even hide, perhaps, politically charged topics that cannot be given open voice. Allusions to the emperors and empresses, even perhaps expressions of our desire for the creation of a new society ... like those Shakespeare included in The Tempest.

But perhaps above all, magic can change people: change who they are and how they behave. The moment I have this thought it creates another mental storm. For this piece seems to accept almost any interpretation, just as it sometimes resists, paradoxically, any interpretation. I begin to feel nervous. Should I be making it full of historical references? Placing an emphasis on the Masonic stuff? Making a popular entertainment? Is it just a comedy, does it mean anything deeper at all, does it. .. does it... ? The singers and conductor are about to return. I have to pull myself together. The pianist is practising the opening notes of the Act II finale.

‘...what always gives me the most pleasure is the silent approval’,

The Magic Flute. A flute that is magic. A flute that can change.

Text: Simon McBurney

Die Zauberflöte today

Die Zauberflöte nu

Die Zauberflöte today

We easily seem to forget — or perhaps we never realised — that the world of Die Zauberflöte is far from harmonious.

When we attempt to reconstruct the events leading up to the story, we find more or less the following: the Queen of the Night was deprived of her power after the death of her husband. Shortly before his death, he voluntarily donates the all-consuming sevenfold sun-circle, the emblem and source of his power, to the Initiates in the hope that their supreme priest Sarastro would ‘manfully’ take control of it. She, the Queen, has been sidelined completely. It is therefore hardly surprising that this unilateral transfer of power has already caused huge tension and enmity between the Queen and Sarastro by the start of the opera.

But the conflict is not restricted to this personal hostility. At the macro level too, the conflict plays out in the dualities between light and darkness, day and night, the sun and the moon, nature and culture, and between man and woman. The world of Die Zauberflöte is a world of divisions, a ruptured community with no place for the paradisiacal complacency in which people move unthinkingly through their surroundings. Only the somewhat naive Papageno appears to be a distant echo of that ideal — appears, because he too ultimately ends up with serious doubts. The young generation has to navigate a world torn apart by the conflict between members of the older generation. Tamino, Pamina and Papageno too are wandering characters, feeling their way, doubtful, vulnerable and often fearful – who can really be trusted in this universe?

Disorientation

This state of uncertainty is expressed at countless points in the text — and it is also the impression the audience gets. Who is good and who is evil? Where and when is this taking place? Indeed, little clarity is given about the time and place of these events. Even the information in the stage directions is sketchy and abstract: a (sacred) forest with a temple, a palm grove, a forecourt with a temple and ruins, a pleasant garden, a pyramid... Die Zauberflöte does not take place in any kind of paradise, despite the presence of nature and gardens.

It jumps around in the time too: the action moves suddenly from night to day and back. The darkness of the moonlit night alternates with the strong light of the sun, then someone is blinded with a sack over their head. The disorientation is constant. Tamino, Pamina and Papageno ask themselves at the start of each new scene where they might be. “Wo bin ich?” (where am I?) is a recurring question. Not only are they wrenched from their background and families, they are also completely rootless and have been abandoned to their fate. Their texts express not only their uncertainty about the time and place but also their doubts about what is real and what is imagined, about truth and lies, about their own identity and that of the other: “Wer ich bin?”, “Wer bist du?” (Who am I? Who are you?).

The entire story of Die Zauberflöte seems to be a quest for some form of anchorage and a way out of this alienating and frightening world. If Die Zauberflöte is a children’s fairy tale, then it is a particularly cruel kind. Horrors, threats, doubts and ordeals are constantly turning up in the story, along with a recurring yearning for death. Only a sudden, overwhelming urge for love seems to offer an answer to the emptiness and sense of being lost that the main characters feel to their core. Vitality and hope can be obtained from love alone — a love that can only be won after taking a treacherous course. If this opera offers any comfort at all, it is solace that comes from a different world — the world of music: “Wir wandeln durch des Tones Macht / Froh durch des Todes düstre Nacht!” (II, 28; By the power of music we walk / cheerfully through the dark night of death!). Strengthened by their love for one another and by the power of music, Tamino and Pamina are able to make it through the most demanding ordeals.

Young generation

This fundamental sensation of existential desperation turns Die Zauberflöte into a story for our times of mankind, and especially the young, in their often precarious existence in the face of uncertainty. This goes further than the Enlightenment optimism that is traditionally attributed to the opera. In the modern context, neither the lost world of the Queen of the Night nor the realm of Sarastro offers a satisfactory answer for the new generation. Their conflict has brought the world to the brink of disaster. Restoration of the previous harmonious situation is impossible, but the alternative proclaimed by the Initiates sounds hollow, inflated and hopelessly esoteric.

The question that Die Zauberflöte raises nowadays is not about the influence of Freemasonry or any other interpretation based on theory, history or alchemy, but the question of where we are headed and who we should choose to lead us. The ideal — which could well have been that of Mozart and Schikaneder too — of liberation through love can no longer be represented today by that strange, elitist group of Initiates. Their appropriation of a monopoly on truth and spiritual welfare, their pseudo-religious leadership with no accountability or possibility of opposition, their misogyny and racism seem suspiciously sectarian and authoritarian. They form a kind of clique who are always right, with all the concomitant dangers.

That the young generation are the only ones not joining in the singing at the close that conveys the moral of the story is a significant, if possibly inadvertent, sign of its fallaciousness. The speed with which the final phrase is ended gives the impression that the rays of sunlight being praised are actually too hot and the young generation wish to escape this dubious glorification. And thus the opera ends with the solution still open. There is no answer, only one new possibility, namely that our love for one another can give us the strength to forge ahead with our lives: “Wir leben durch die Lieb’ allein.” (I, 14) — it is through love alone that we live.

Text: Luc Joosten

Een pleidooi voor Monostatos

Een pleidooi voor Monostatos

A plea for Monostatos

The libretto of Die Zauberflöte contains expressions and judgements that would be deemed at the very least inappropriate and possibly even offensive by modern standards. They continue to be hotly disputed — and rightly so. Without wishing to gloss over the points of contention, some of the criticism is unfortunately the result of an inaccurate reading of the libretto. Back in the 1980s, the German musicologist Atilla Csampai made a critic’s appeal for a re-evaluation of the figure of Monostatos.

How ‘enlightened’ or ‘humane’ a hierarchical system truly is can best be judged by those who occupy its lowest ranks. In Sarastro’s kingdom there are slaves. And there is Monostatos, their miserable overseer. He is the stumbling block in all the bourgeois interpretations, which treat him no better than Sarastro, namely as an inferior being who does not deserve the same human dignity as the higher-ranked characters. But even if you were to accept the discriminatory nonsense that Monostatos is a malicious monster, that would not alter the fact that he is a part, and therefore a product, of Sarastro’s world, a pure slave society. He is the real touchstone for the credibility and humaneness of the priestly moral system. Like a chained dog, Monostatos does not even theoretically have a chance of climbing up to the ranks of the initiated (something Papageno is allowed to try), let alone being given the prospect of a “girl or woman” of his own some day. Is it any wonder he falls in love with Pamina when a sunray from her alights on his trampled soul? Is there a man in this opera capable of being unmoved by Pamina’s grace, her inner beauty?

Sarastro himself, the “divine wise man”, is unable to contain his strong feelings for her for one moment. Even the much-cited and atrociously moralistic ‘Hallen’ aria (no. 15) is nothing other in its musical diction than a covert, lachrymose declaration of love by Sarastro to Pamina. From this perspective, his ostensibly arbitrary punishment of Monostatos involves a certain degree of involuntary jealousy on the part of a rejected despot who – being easily offended – takes out his wounded pride on the nearest subordinate and is perhaps unable to admit to himself that a barbarian, an underdog like this, might be moved by the same emotions as him, the divine Zoroaster.

Social affinity

In contrast to Sarastro, and previous interpreters of the text and drama who have painfully closed ranks against Monostatos, the authors themselves, that is to say Mozart and Schikaneder [...], leave us in no doubt as to whose side they take. Schikaneder lets Papageno clearly express his unprejudiced attitude to this poor creature: “There are certainly black birds in the world, so why not black men as well?” (I, 14). But Mozart goes a step further and “unmasks” Monostatos’ “danger” every time he acts threateningly, maliciously or villainously by using lovingly tender, buffoon-like music to paint his actions as the innocent threats of a vulnerable being. And could Mozart have done any better in persuading us of the equivalence of Monostatos and Papageno, the affinity in their social status, than by giving them both an identical musical treatment in the ‘Recognition’ scene (trio no. 6, from bar 53): when the Moor and the bird-catcher first meet, each believes the other must be Satan in the flesh. Both stand there trembling from fear, stammering the same words: “Aah! That must be the devil!” And then Mozart also dedicated the small, sad, tender pianissimo aria in the second act (no. 13) to the black man, in which Monostatos’ sensitive, fearful, battered soul achieves a moment of unnoticed fulfilment. Is it not downright pitiful to see this creature, degraded to the position of a dog by the Initiated, evoking his status as a human being and asking, “Do I not then have a heart? Am I not flesh and blood?” Ultimately, he even apologises to the moon, his only witness, for his sacrilegious but in essence perfectly innocent kiss.

It is neither “lascivious and one-dimensional”, as Wolfgang Hildesheimer and all other earlier Mozart biographers liked to see it, nor a “projection on Monostatos” of Pamina’s “sexual” desires, as Rainer Riehn fantasises, but a subtle musical psychogram of an outcast, a debased man whose neck has already been broken by the “Initiated”. For these few moments, Mozart clearly extends the protection of his human empathy to the deprived man, because here he retrospectively grants him the honour that Schikaneder’s fairy-tale plot had only intended for Tamino and Papageno — as symbols of human expression. Analogously to Tamino’s magic flute and Papageno’s faun flute, Mozart gives Monostatos a piccolo — even if only musically, as an instrument in the orchestra. Can a more significant upgrading of a minor character be imagined in an opera that revolves around a magic flute?

The humane message of the music

It is also no coincidence that it is Monostatos and the slaves who are receptive to the purifying power of the music (in the first finale): they have not yet been sufficiently alienated and are therefore still capable of being transfixed by the humane message of the music, symbolically caught in the magic of the bells. Why do neither Tamino nor Papageno come up with the idea of trying out the same magic charm on Sarastro, who is threatening them? They realise this would be pointless because Sarastro is insensitive. The humanising powers of the magical instruments might be able to calm slaves, Moors and wild animals but certainly not Sarastro and his men, whose kingdom is a place where pure reason conquers all, logic that rejects not only all the old magic but also every uncontrolled feeling, every form of emotional openness. After all, neurotic oppression and arbitrary treatment are easier to enforce with cold, rational calculation.

Text: Attila Csampai

Programmaboek

Become a Friend of Dutch National Opera

Friends of Dutch National Opera support the singers and creators of our company. That friendship is indispensable to them, and we are happy to do something in return. For Opera Friends, we organise exclusive activities behind the scenes and online. You will receive our Friends magazine and have priority in ticket sales.