The Shell Trial

Performance information

Voorstellings-informatie

Performance information

The Shell Trial

Ellen Reid (1983)

Duration

1 hour and 45 minutes, no interval

This performance is sung in English

Dutch surtitles based on the translation of Willem Bruls

Opera in three acts

Makers

Libretto

Roxie Perkins

based on the play De zaak Shell by Anoek Nuyens and Rebekka de Wit

Musical direction and co-creation

Manoj Kamps

Stage direction, concept and co-adaptation

Romy Roelofsen (Het Geluid)

Gable Roelofsen (Het Geluid)

Set design

Davy van Gerven

Costumes

Greta Goiris

Flora Kruppa

Lighting

Jean Kalman

Video

Wies Hermans

Choreography

Winston Ricardo Arnon

Movement director ‘Elders’

Nita Liem

Dramaturgy

Willem Bruls

Saar Vandenberghe

Jasmijn van Wijnen

Cast

The Law / The Artist

Lauren Michelle

The CEO

Audun Iversen

The Government

Claire Barnett-Jones

The Consumer

Antony León

The Activist

Ella Taylor

The Fossil Fuel Laborer

Allen Michael Jones

The Pilot

Alexander de Jong

The Historian

Jasmin White

The Climate Refugee

Carla Nahadi Babelegoto

The Field Worker

Yannis François

The Elementary School Teacher

Nikki Treurniet

The Weatherman

Erik Slik

Academists and members of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra

Watermusic Kinderkoor (Muziekschool Waterland), Noord-Hollands selectiekoor, The Shell Trial project chorus, B! Music school en Leerorkest Zuidoost

Chorus master

Lea Cornthwaite

Commission and co-production of Dutch National Opera, Het Geluid Maastricht and Bregenzer Festspiele, in collaboration with Opera Philadelphia

Production team

Assistant conductor

Aldert Vermeulen

Assistant director

Meisje Barbara Hummel

Junior assistant director

Tessa Kortmulder

Assistant director during performances

Meisje Barbara Hummel

Rehearsal pianists

Bretton Brown

Laura Poe

Language coach

Bretton Brown

Stage managers

Marie-José Litjens

Lucia van der Pasch

Showcaller

Jossie van Dongen

Artistic planning

Margot Vervliet

Costume production assistant

Maarten van Mulken

Master carpenter

Jop van den Berg

Lighting manager

Peter van der Sluis

Props master

Niko Groot

Props team leader

Jolanda Borjeson

Special Effects

Koen Flierman

Ruud Sloos

First dresser

Jenny Henger

First make-up artist

Frauke Bockhorn

Sound technician

David te Marvelde

Orchestra representatives

Dorien de Bruin

Isabelle Nassenstein

Head of music library

Rudolf Weges

Surtitle director

Eveline Karssen

Surtitle operator

Irina Trajkovska

Set supervisor

Mark van Trigt

Production management

Emiel Rietvelt

Sustainability coordinator

Julie Fuchs

Het Geluid

Artistic direction

Romy Roelofsen

Gable Roelofsen

Business direction Het Geluid

Rick Busscher

Board foundation Het Geluid

Guus van Engelshoven

Nadine Bemelmans

Pam de Sterke

Participation projects

Project management

Het Geluid

Production management

Eva Banning

Neighbourhood coordinators/music teachers

Brenda Jonker

Soumeya Bazi

Saly Ndoye-Roozen

Valeria Mignaco

Natali Boghossian

Rachai Beumers

Agri Issa

Advisory participation projects

Rochelle van Maanen

Handan Aydin

Kimberley Smit

Mina Ouaouirst

Ebony Jones

Des Balentien

Rosita Zaalman

Tessa van Lier

Jeritza Toney

Chorus conductor and consultant

Lea Cornthwaite

Chorus advisor

Suzi Zumpe

Vocal advisor and coach childrens soloists

Kirsten Schötteldreier

Conductor Noord-Hollands Selectiekoor

Josephine Straesser

Conductor Watermusic

Karen Langendonk

Artistic leader Watermusic programme

Michael Hesselink

Coordinator Watermusic programme

Maartje Mostart

Muziekcentrum Zuidoost / Leerorkest

Marco de Souza

Jacco Minnaard

Mirte Moes

Assistant movement director ‘Elders’

Jopie de Groot

Project assistant ‘Elders’

Natacha Triest

Recruiters ‘Elders’

Marian Dors

Jules Rijssen

Annemarie Tiebosch

Winny Arnold

Yvette Albertzoon

Saundra Williams

Gregory Shaggy

Delano Mac Andrew

Annet Zondervan

Fundraising

Saar Vandenberghe

Education, Participation en Programming department of Dutch National Opera & Ballet

Mechteld van Gestel

Wout van Tongeren

Ineke Geleijns

With special thanks to

Glenn Helberg

Dat!school Noord

Amsterdams Andalusisch Orkest

Anno Pander

Paulette Smit

Sjaiesta Badloe

Brian Lo Sin Sjoe

Marjo van Schaik

Anja ten Klooster

Elisia da Silva Martins Peças

Kitlyn Tjin a Djie

Anne Büscher

Isa Kasten

Weini Woldu

Nancy Jouwe

Chris Julien

De Vrouw met de Baard

Carl Lemette

Mas van Putten

Academy of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra

For the past two decades, the Academy of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra has served as the training facility of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra. Top European talents complete their musical education with a personal development route within the orchestra’s wings. The Concertgebouw Orchestra collaborates with the Academy to bridge the gap between conservatory and professional practice. The adaptable programme prepares outstanding players for a career in one of the world’s most prestigious symphony orchestras. The Academy also serves as a breeding ground for the Concertgebouw Orchestra. Students are immersed and taught in our orchestral culture’s traditions, and they learn how to perform together in specific ways such as taking responsibility, trusting one another, listening to one another, and taking risks. The Concertgebouw Orchestra perpetuates an important tradition through its Academy. The Concertgebouw Orchestra today includes no fewer than fifteen former Academy members.

For The Shell Trial, the orchestra is made up of academists and former academists, as well as a few KCO orchestra members, one of whom is also a former academist.

First violin

Borika van den Booren

Ilka van der Plas

Diet Tilanus

Marie Duquesnoy

Marijke van Kooten

Miranda Nee

Second violin

Coraline Groen

Lonneke van Straalen

Laura Lunansky

Esther Frey

Igor Pollet

Viola

Vilem Kijonka

Sofie van der Schalie

Javier Rodas

Mark Mulder

Cello

Charles Watt

Nualla McKenna

Klara Wincor

Simon Velthuis

Double bass

Georgie Poad

Riccardo Baiocco

Piccolo/fluit

Luna Vigni

(Bass) clarinet

Valentina Pennisi

Horn

Fons Verspaandonk

Trumpet

Álvaro García Martín

Bass trombone

Marijn Migchielsen

Percussion

Elias Blanco

Ramon Lormans

Arjan Jongsma

Piano/synthesizer

Daan Kortekaas

In a nutshell

In het kort

In a nutshell

The trial

On 4 April 2018, the environmental group Milieudefensie (part of Friends of the Earth International) announced it would go to court if Shell did not bring its business operations in line with the Climate Agreement. Thousands of individual Dutch people and a group of NGOs joined as co-claimants in the lawsuit against Shell. They demanded a drastic reduction in carbon emissions. Research had shown that since 1965, only six other companies in the world had emitted more carbon dioxide than Shell. And what was Shell’s defence? That the consumers should change, not us. That was despite Shell already having known in the 1980s that the Earth would become warmer and that the fossil fuel industry was the main cause. In 2021, Milieudefensie won the lawsuit. The court ruled that Shell must have reduced its CO2 emissions by 45% by 2030 compared with 2019. Shell has appealed against the ruling, arguing that requiring one single company to become more sustainable is not effective. In the meantime, Shell is required to comply with the ruling, but the company had not taken any action one year after the judgment. The appeal proceedings will start on 2 April 2024, two weeks after the world premiere of The Shell Trial.

De zaak Shell

Theatre makers Anoek Nuyens and Rebekka de Wit discovered that Shell had been prepared for this lawsuit for a long time. The company has long had a scenario department that works out various scenarios for the future — including the one that has now come to pass. Nuyens and De Wit have been closely following the climate debate for years. They attended the shareholder meetings of multinationals, read the speeches and interviews of Shell executives, ploughed through government agreements and policy memorandums, and systematically noted the comments by relatives whenever the climate crisis got discussed at Christmas dinners. They wrote down the pleas made by various key figures in the climate debate, which they brought together in their play De zaak Shell (The Shell Trial, 2020). Their premise was the climate crisis is a crisis of responsibility. No one knows any more who exactly is responsible for what. In De zaak Shell, they created their own scenario department in which all the voices in the debate could practise their roles.

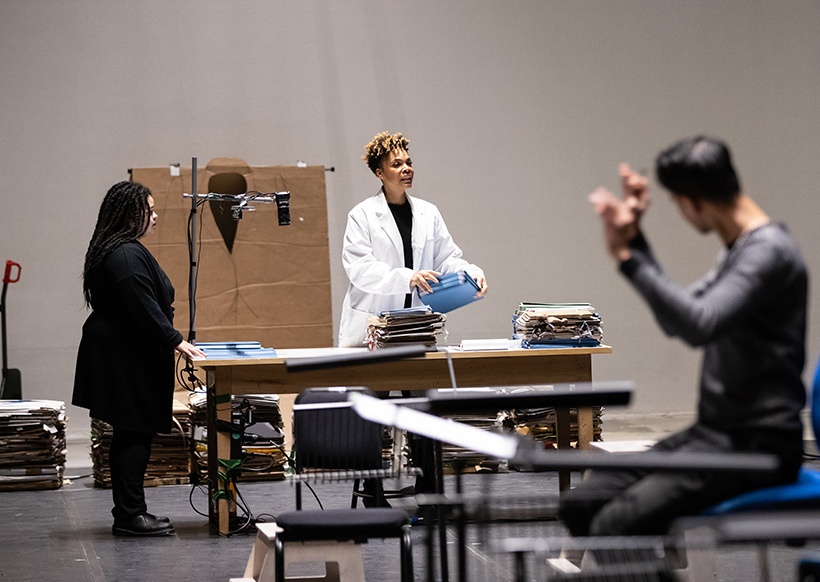

The opera: The Shell Trial

Director duo Romy and Gable Roelofsen joined forces with co-creator and conductor Manoj Kamps to adapt the play for the opera stage as a way of introducing the topic to an even wider audience. They asked librettist Roxie Perkins and composer Ellen Reid to help them make this challenging adaptation. They kept the play De zaak Shell as the point of departure; however, the opera treats the climate crisis not just as a modern-day problem but also as a problem with a long colonial history. The introduction of new voices, voices that are often ignored in the debate, adds this extra nuance to the work. There is The Historian, who creates room for voices from the past to be heard, and The Climate Refugee, representing all the people who had to flee their country as a result of the actions of companies like Shell. The Shell Trial is thus a plea for us all to look ahead, while not forgetting the history that brought us to this point.

Sustainable production

This opera, which explores the allocation of responsibility in the climate debate, also puts the spotlight on Dutch National Opera’s own responsibility for reducing its emissions in its production processes. With sustainability coordinator Julie Fuchs at the helm and thanks to the introduction of the Green Deal, it was possible to produce The Shell Trial with an extremely low environmental footprint. For example, 82% of the materials used for the production are recycled materials. Opera’s international character does mean that plane journeys are inevitably a significant factor and the main source of environmental impact in what was otherwise a highly sustainable production process, even though the emissions were compensated as much as possible. The sustainable production process for The Shell Trialis a pilot for producing opera sustainably.

Multicultural and intergenerational

The climate issue is a problem that affects everyone in the world. That is why the cast and team include people from different generations and with diverse cultural backgrounds. Two participatory projects took place in the preparations for The Shell Trial. Firstly, a chorus was formed of children from Amsterdam Zuidoost, Noord, Almere, Nieuw-West and Purmerend. Secondly, a group of seniors with roots in former Dutch colonies was formed. As well as performing, they also inspired the creative process by sharing knowledge, ancestral rituals and innovative views on climate issues.

Synopsis

Korte inhoud

Synopsis

In a prologue The Artist introduces the audience to the current lawsuit against Shell. She invites the audience to think of this evening as a rehearsal for the future where everyone can examine whose responsibility it is to solve the climate crisis.

I

In a metaphorical courtroom figures representing The Law, The CEO of Shell, and The Government ponder the potential consequences of the Shell Trial and attempt to avoid blame for the warming planet.

II

The piece moves into the real world. We meet characters with less structural power as they question what their individual responsibilities are in the face of climate change. These figures include The Consumer, The Activist, The Fossil Fuel Laborer, The Airline Pilot, The Historian, The Climate Refugee, The Weatherman, The Elementary School Teacher and The Fieldworker.

The atmosphere becomes confrontational as these characters struggle with eco-anxiety and guilt over how their livelihoods are entangled with the oil industry. As each character battles their feelings of helplessness and rage, it is revealed that no one’s future is exempt from the environmental, political, and personal consequences that emerge from the Shell Trial.

Frustrated by inaction, these characters unite to resist the passivity of The Law, The CEO and The Government. However, they are overpowered returning the world to the status quo. Almost…

III

The Artist steps out of her previous role, mourning for all of those lost and opening up a door to the past.

Transcending time and space, children from The Past emerge. Their voices create an eerie and vast landscape, illuminating Shell’s environmental negligence and the Dutch colonialism that enabled Shell Oil’s fortune.

Children from The Past and The Future confront the audience, urging them to act now while they still can.

The Historian’s timeline

De tijdlijn van de Historicus

The Historian’s timeline

In the libretto, The Historian refers to some of the many occasions when Shell caused immense damage to people and the environment – damage for which Shell has never admitted responsibility. The references are to the following events.

1595 – Indonesia

The first Dutch expedition to the Indonesian archipelago took place in 1595. It led to colonisation of the area by the Dutch, which ultimately enabled the foundation of Shell as a company. Shell would first drill for oil on the island of Sumatra.

1634 – Curaçao

The island of Curaçao was ‘conquered’ in 1634 by the Dutch West Indies Company. This led eventually to Shell establishing an oil industry on the island.

1976 – Ogoni

Between 1976 and 1991, spills of Shell oil in Ogoniland in Nigeria amounted to more than two million barrels. These spillages caused huge suffering among the local people due to the large-scale contamination and social unrest. This culminated in the 1990s with the wrongful imprisonment of nine Nigerian activists who were protesting against Shell. They included the author and human rights activist Ken Saro-Wiwa. The nine activists were condemned to death and hanged. In 2009, Shell agreed a settlement in a lawsuit brought by Saro-Wiwa’s family and other surviving relatives of the activists. Despite this, Shell continues to deny culpability for the death of the Ogoni Nine or the extensive contamination in Nigeria.

1988 – Californië

In 1988, there was a devastating oil spill in the San Francisco Bay area. The spillage of 400,000 litres of crude oil caused immense damage to the environment. Shell agreed to pay for the restoration of the land but the incident still had a widespread impact.

2016 – Mexico

In 2016, Shell was responsible for an oil spill of 90,000 litres in the Gulf of Mexico. Shell claims to have recovered the bulk of the spill, but toxic pollutants are still affecting the quality of the water and the health of communities bordering the area.

2021

In 2021, a Dutch court ruled in favour of the NGOs and activists who had brought a lawsuit against Shell. Shell was found guilty of the irreparable damage it had caused to people and the environment.

Text: Roxie Perkins

An accumulation of perspectives

Stage directors Romy Roelofsen and Gable Roelofsen, and conductor and co-creator Manoj Kamps on The Shell Trial

An accumulation of perspectives

Some topics are on such a grand scale, so existential, unfathomable and overwhelming that you know immediately they deserve to be treated in an opera. When there is already an amazing play to build on, the question is what do you lose, and above all what can you gain, by turning it into an opera? While the script of a play can deal with the facts in detail, almost like an essay, an opera libretto has to be more compact: the language has to be condensed and poetic. That only works for huge issues like the climate crisis, which make demands on our intellectual capacities but also affect us emotionally. While the play poses difficult questions about the present day and the future, opera as an art form can also bring history –cultural history – to life, letting us hear and see the past. A play communicates through words and images. In opera, we feel what is not said even more strongly through the music.

Acknowledging the shared problem

Like the original play De zaak Shell (The Shell Trial), our opera is an accumulation of perspectives in society that together form a system. However, we have expanded the number of voices: we have given the past a say too and turned the story into a global affair. What major forces are at play and how do they interact with one another? Traditionally, opera is an effective medium for reflecting on power, in part because of its roots in both elite and popular culture. It also offers a space for contemplation, a tradition that can be traced back to church music and oratorios. Furthermore, opera is the perfect vehicle for portraying huge archetypal forces. The writers of the original play gave us clear-cut modern-day archetypes that go beyond individuals with simplistic psychology.

The issue of responsibility for the climate crisis is often presented in the form of caricatured contrasts, but the world is more complex than that. In this opera, we want to move beyond entrenched positions and acknowledge that we have a shared problem. In the stage direction, we present the voices and structures that jointly make up the system. The orchestra too is a ‘body’ that makes its own statement on the stage. This staging is faithful to a European, Brechtian tradition of theatre without the fourth wall, while at the same time referencing an oratorio performance or church service.

Colonialism – capitalism – climate crisis

Ellen Reid’s music is both accessible and disorientating in the contemporary style thanks to her eclectic palette of sounds. As the different perspectives accumulate, the musical idiom becomes increasingly raw and modern, in a way that does justice to the confusion, alienation and numbness that this topic can instil in people. We are reminded that the disasters awaiting the Global North are already taking place in the Global South. The libretto is not afraid to make the link between colonialism, white supremacy and capitalism, which still has consequences today and which is at the root of wars, genocide, exploitation and other horrors committed in the name of the Western world. “You will feel so safe, as if our countries were not connected by the same seas,” sings The Climate Refugee. “And when your home is swallowed by the Earth, you will say it is not fair.”

We see a great symbolic value in the fact that this opera will be premiering in the cultural centre of the Netherlands, in a building that also houses the city council of Amsterdam, a city inextricably linked with capitalism and exploitation. “How many of the ivory towers I enter every day were built with stone from distant shores where I could have been raised?” sighs The Historian.

An intergenerational conversation

While opera, as one of the most expensive art forms, has a long and often dubious history of sponsoring, patronage and association with the aristocracy and elite, we are now seeing a new trend in various opera houses around the world, as new audiences want to see the major stories of our time turned into operas. Long before the establishment of the Opera Forward Festival, Dutch National Opera had an impressive tradition in doing this. We hope our work will continue this long tradition and at the same time broaden the opera experience further still. We seek to nurture the conversation between the classic older opera audiences, their children and grandchildren, and other young people around them. We also hope that our choices of subject matter, composers and approaches will appeal to a wider range of people, and make them feel welcome at the opera and free to become involved in the conversation.

For this opera, we explicitly opted for a creative process that was intergenerational — in the team, the cast, the orchestra and the supporting organisation. We are also pleased that — thanks to certain funds — we were able to bring in performers with experience outside the world of classical music to give us a new angle. Each perspective in our production is represented by the body and/or voice of the performer, whereby their humanity, in all its power and fragility, is our focus at all times.

The ‘we’ culture

In this production, we worked with various consultants, including the psychiatrist Glenn Helberg. Helberg gives talks in which he distinguishes between the materially oriented and the non-materially oriented, the difference between the ‘I’ culture and the ‘we’ culture. The ‘I’ culture is geared to individual profit, acquiring tangible objects and riches. The ‘we’ culture takes a broader view: what is sustainable and acceptable for the group? It focuses on the connection with one another and with natural resources. It concerns values that cannot easily be quantified or captured in concrete terms. Many cultures and peoples are labelled ‘primitive’ in the capitalist, Western worldview, which judges them against conservative ideas of civilisation and Enlightenment. In this dichotomy, cultures that are not oriented towards financial gain at the expense of other people or resources are precisely the ones that are viewed as uncivilised, backward and primitive.

Our research for this opera and our experience working on it have only made it clearer to us how much of a driving force capitalism is in this dominant mindset that enables the destruction of the climate. Essentially, capitalism means reducing all aspects of our world to factors that can be used to make a profit. It objectifies everything: plants, animals, land, water, sunlight, even other people. This exploitative relationship with respect to people, the planet and nature harms the planet and ultimately us too. Whereas the individual’s own interests take priority in the ‘I’ culture, the irony is that in the long term this attitude actually harms those interests. The ‘we’ culture is not about an exploitative worldview purely geared to individual achievements and profit, but about the ecology of the community, which affects the community’s relationship with the planet.

The changing times and the crises we are facing demand a shared approach in which the group provides a safety net, with a collective solution for individual problems. “Cherishing slowness”, as The Government sings, is not a realistic option. The climate crisis is not ‘business as usual’. What the human race no longer has in abundance is time.

Text: Manoj Kamps, Romy Roelofsen and Gable Roelofsen

“This is the great burden that now rests upon writers, artists, filmmakers and everyone else who is involved in the telling of stories: to us falls the task of imaginatively restoring agency and voice to non-humans. As with all the most important artistic endeavours in human history, this is a task that is at once aesthetic and political — and because of the magnitude of the crisis that besets the planet, it is now freighted with the most pressing moral urgency.”

Amitav Ghosh, from The Nutmeg’s Curse (2023)

The theatre as a space for reflection

Dramaturge Willem Bruls on The Shell Trial

The theatre as a space for reflection

It is a well-known and often-cited development in the history of the performing arts: Greek theatre came into being when the first experiments with democratic government were taking place in Athens, in the fifth century BCE. A society that felt a need for political emancipation immediately came up with a corrective system alongside it. In other words, the social problems could not be resolved through debates alone. What was also needed were reflection, abstraction, exploration and re-enactment. Theatre let social problems be formulated explicitly and acknowledged — because there was not always a clear-cut answer or solution. Theatre kept society healthy because it created a sense of shared identity and solidarity. The same applies to many non-European theatrical traditions.

A central theme in Greek theatre is how personal responsibility relates to the responsibility of society as a whole. Should you always abide by the laws of a country, even if that goes against your inner sense of justice? Should Antigone bury her brother or should she obey the law laid down by her uncle, King Creon? Should Extinction Rebellion be allowed to block the A12 motorway? These questions don’t really have a good answer. But if dilemmas cannot be resolved through a public debate, there is always the legal system. In a play by Aeschylus from 458 BCE, Orestes is ultimately tried before a court of law for his deeds. In 2020, the theatre makers Anoek Nuyens and Rebekka de Wit wrote a play about the trial of Shell in a lawsuit brought by various private individuals and NGOs, including the environmental group Milieudefensie (part of Friends of the Earth International). The complexity of the climate problem and the question of individual responsibility had become too big. It was time for reflection.

Political opera

Contrary to what you might think given its reputation, opera as a genre has always been political, making both direct and indirect statements. All those powerful stories of love and lust, passion and revenge, betrayal and surrender have a political message, or at the very least play out within a particular political context. To give one example among many, when Giuseppe Verdi wrote La traviata in 1853, he had the oppressive political and religious attitudes of his own country in mind. In fact, he personally suffered the condemnation of his society’s double standards when he lived with his unmarried lover Giuseppina Strepponi. His opera questions patriarchal power. But the political context can be more direct than this. When Life with an Idiot, by the composer Alfred Schnittke and librettist Viktor Yerofeyev, premiered at Dutch National Opera in 1992, it was only a year after the collapse of the Soviet Union. No one could fail to see the deeper meaning of the story, a parable about a family that is forced to take in an ‘idiot’ and is torn apart as a result. In this opera, artists reflected for the first time on recent events in their country.

Dutch National Opera has a modest tradition of staging explicitly political operas. That includes the works of the American composer John Adams, such as the European premiere of Nixon in China in 1988. In 2018, Das Floß der Medusa by the German composer Hans Werner Henze was performed in Amsterdam. This oratorio was a product of the politically charged 1960s. Oedipus Rex by Igor Stravinsky is another work that fits in this category. On paper, it is an oratorio based on the Greek tragedy of Oedipus, but in reality it is an opera on the tragic consequences of political incompetence. It is also a work where personal responsibility can no longer be distinguished from the interests of society.

In 1991, De Munt in Brussels staged the world premiere of John Adams’ The Death of Klinghoffer, a controversial opera dealing with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. These are all works that played a role and were sources of inspiration in the creation of The Shell Trial. What they demonstrate is that they all contribute to the debate as significant works of music theatre.

Trial that sets an example

The question of responsibility for society’s problems is at the heart of The Shell Trial. The responsibility of a community, a corporation, the individuals within that corporation, and the many other social actors such as politicians, scientists, educators and so on. Everyone plays a role; everyone acts. However, the arguments, claims and presentations of ideas do not seem to have led to solutions as yet. Like Oedipus, we are all trapped in a tragic series of events that we jointly set in motion, either voluntarily or involuntarily. The big question is whether a court case resolve anything. Yes and no.

No, because a court case does not have a direct impact on climate change. It would help hugely if Shell were to reduce its emissions by 45% by 2030. But to actually reverse climate change, all other companies around the world would need to do the same.

Yes, because like a political play or opera, a trial can set an example. It could become a parable itself in the future that raises awareness and serves as a clarion call for change. How can we find solutions within the opera that we could apply at the various levels?

A requiem for humanity

The Shell Trial is not an obvious opera in the classic sense of the word, neither in its form nor in its creation process. The makers found themselves in a paradox: producing a work in this complex, expensive art form inevitably entails an adverse environmental impact. What is more, opera is automatically seen as representative of an economic and cultural elite, and thereby dismissed as an exponent of the status quo and the failure to act. Opera is also constantly criticised as too left-wing, too right-wing, too expensive, too elitist, too woke or too White. That is interesting because it only serves to show the prominent political position of opera. The Shell Trial is an opera that has its roots in the spirit of the oratorio, the passion play, playing with compassion. It is a requiem for humanity. The original play ends with the words of an activist. She concludes, “And while the court gives its ruling, the last islanders in the Pacific Ocean will glide over their homes, back and forth, in a canoe, in the hope that perhaps something will float up, a reminder that it once existed.”

Text: Willem Bruls

How we treat one another is how we treat nature

Dramaturge Saar Vandenberghe on two social and artistic processes at the heart of The Shell Trial

How we treat one another is how we treat nature

A total of 108 people of ages ranging from 10 to 80 will take the stage in The Shell Trial. Together, they call on us to shoulder our responsibility in the fight against climate change and they ask how we can make life on Earth fairer in future. Just as Lauren Michelle considers points of view in her role as The Law that are often suppressed (the historical context, the reality of climate migration), on stage we see people from groups who have normally rarely been given this opportunity in the Western opera tradition, except perhaps as the exotic Other. Two groups have been on a fascinating journey in the preparations for the premiere.

Seniors

The twelve older performers, The Elders, all have roots in former Dutch colonies, places that have suffered pollution and devastation in the past, often at the hands of companies such as Shell.

“My mother was born on Aceh in the region where Shell first started drilling for petroleum in 1892, when it was still called ‘Koninklijke Olie’ – Royal Oil.”

Nita Liem, movement director for The Elders

But in addition to this painful past, The Elders also offer a key to the future. In the search for new techniques that can heal nature, it is becoming increasingly clear how important the centuries-old knowledge is that has been passed down through the generations of indigenous communities. These ‘we’ cultures are geared to a liveable world for the community and thereby offer an alternative to the capitalist worldview that mercilessly exploits everyone and everything. The voice of the ‘we’ culture is embodied by The Historian, played by Jasmin White, who is a member of the Cherokee Nation in Grand Ronde, Oregon. The movements of The Elders are also based on the knowledge and rituals passed on to them by their forebears. For eight Saturdays in a row, they gathered to eat, talk and dance together.

William calls out the rhythm: Yatta! Twelve pairs of hands remove an imaginary kris (Indonesian dagger) from its sheath and ritually stab someone’s footprint. They drew inspiration for this from Raymonde who told them about the kris that her Indonesian-Dutch family had received as a gift and how awkward it made her feel having such a weapon in the home. Ingrid fiddles with her Ala Kondre necklace, as colourful as she is herself. That fiddling becomes an abstract movement, as if a story is desperate to break free from each throat. The costume designers Greta Goiris and Flora Kruppa ask The Elders about the form and meaning of traditional garments. Twie has a shawl with her, one of the few items her parents were able to take when they fled Indonesia for Suriname in 1962. She wraps it around her with her good arm. The gesture becomes an elegant dance movement, an echo of this flight.

“Even if the audience don’t know where the movement comes from, they will still be fascinated by it if you perform with dedication,” Nita tells the group. “That deep knowledge — that is your capital”. She aims to say as much as possible with the minimum of individual movements, like a calligraphy of gestures in space. Because the exchanges take place on an equal footing in this co-creation process, The Elders literally and figuratively occupy their own place on the stage as non-professional performers. Each body is an archive full of stories and history lessons from their ancestors.

“My family is fighting Shell because they want to drill on our plantation of Saramacca in Suriname. This will cause irreversible damage to the nature there. My mother always urged us to protect the land. It’s quite unacceptable these days to mess everything up, then just turn around and leave.”

Linda Grootfaam, one of The Elders

Everyone stands up and silently looks for the moon. The stage ceiling turns into a night sky that spans worlds and eras; the rehearsal room throbs with emotion and energy.

The youth

“Some of you can read sheet music, some of you will learn the music from MP3s, but that doesn’t matter. The important thing is to feel what you are singing!” Fifty-one children and adolescents fix their gaze on London conductor Suzi Zumpe as she starts the rehearsal. They come from all over Amsterdam and its satellite towns. Two months ago, most of them did not know one another, but now they are performing together in the The Shell Trial project chorus. The libretto describes their role as “Vessels of the past and the future”. Vessel can mean both container and ship. They represent nothing less than the voice of humanity as a whole. Indeed, the group is much more culturally diverse than the youth choruses that are normally seen and heard on the opera stage.

Like The Elders, these youngsters are more than just performers. They embody a generation whose future is threatened by global warming.

“These aren’t random songs. This opera is about a serious matter. We need to have a healthy planet and healthy air left for young people. That’s only possible if people do something and don’t make it worse than it is already.”

Jenae (12)

The choreographer Winston Arnon asks everyone to slouch in their chairs and then sit bolt upright. “Do you hear the difference in your voice?”The group works hard on moving in unison to the beats of Dua Lipa, each being urged to take up their own space on the stage. Anyone who finds that nerve-racking gets warm encouragement from the rest of the group. Conductors Karen and Josephine are beaming. Teacher Valeria also sees her pupils growing in their role: “They are discovering new material that’s outside their comfort zone, and enjoying it. Working as an ensemble with children from different schools and with different backgrounds lets them discover their own personalities.”

During the break, three singers from Amsterdam’s Zuidoost district quickly film a TikTok clip in the corridor. They feel quite at home in the group and in the Dutch National Opera & Ballet building. Teacher Natali emphasises the effect role models like Winston, the directors and the diverse cast have on the impression that her pupils will get of opera and their own future. Luka and J’nyell are playing a game of Brawl Stars. Then there is complete silence as they listen for the music that plays just before the children’s chorus enters the stage. J’nyell (10) whispers, “This music is scary and beautiful at the same time. It tickles my soul!”

Afterwards, the directors have to deal with a torrent of questions. “When will we get to rehearse on the proper stage? Isn’t it too loud if we walk so close past the orchestra? Will the audience be able to see us?” “Have we really only got five more lessons until the show?” asks J’nyell. He takes a deep breath and continues singing, even more loudly.

The adventure won’t end for these youngsters after the last performance, as there will be a spin-off. The plan is for a family opera about climate change to be produced in 2025, with music by a Dutch composer, and sung and written by this chorus. This is how Dutch National Opera is building a long-term relationship with these talented youngsters.

“Our bodies are our own piece of nature. How we treat one another is how we treat nature.”

Nita Liem

Text: Saar Vandenberghe

Elders

Nita Liem

Ingrid Coleridge

Claudia Tjon Soei Len

Twie Tjoa

Francisca Tan

Raymonde Roebana

Beppy Milder

Patrick Altenberg

William Mettendaf

Linda Grootfaam

Anna Azijnman

Anneroos Burger

Children

May-Li Crichlow

Jenae Esajas

Dunyah Diallo

J’nyell Horb

Amanda Slotboom

Annelly Rosario Tiburcio

Jahcyra Smith

Sigwendeley Felter

Luna Urosevic

Miriam Mikhail

Raïsa Purperhart

Kayden Grotewal

Tessel Bavinck

Liz Patey

Juliëna Imang

Nesli Sen

Salena Laghzaoui El Azrak

Manja Stalij

Zoë Ristra

Benjamin Bakker

Rani Willy

Hendrika Fiankson

Phyllis Kwaning

Faustina Ntiamoah

Jacquelineblu Radway

Monezra Rudge

Sonakshi Bhulai

Shirin Sanakulova

Shahlâ Aslantürk

Eline Noë

Isha Raghoebarsing

Selena Hendriks

Luka Xavier Dias Da Silva

Julia Buyskes

Ezinne Nzeribe

Paulien Kok

Sien Molenaar

Zerlina Jansen

Elin van den Munckhof

Tessel van Staveren

Chaira Da Silva Neto

Caya Vugts

Daphne Bommer

Joris Zweed

Julia Hertog

Lot Jonk

Sofie Out

Valerie Brak

Ymke van de Hoef

Luna Andrea

Benthe Bottema

Anne-Sophie Bonhof

Bekijk hier de printversie van het boek